Catalog of Chaucer’s Works

The list below shows the works of Geoffrey Chaucer cited in this document, including all his major writings, with a brief indication of the contents and significance. Titles of longer works are shown in italics, shorter in “quotes.”

“Adam Scriven”: See: “Chaucers Wordes unto Adam, His Owne Scriveyn”

The Book of the Duchess. Chaucer’s earliest datable work, and very possibly his earliest surviving writing (unless the French poems attributed to “Ch” are by him). It was written as an elegy to Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster, wife of John of Gaunt. She was, by all accounts, beautiful and virtuous, and died in 1368 or 1369 while still in her early twenties. Gaunt seems to have genuinely loved her, and Chaucer wrote to console him. The book is a dream-vision in which Chaucer meets first the grieving Alcyone (of Greek mythology) and then encounters Gaunt in the guise of the Black Knight and hears his sad story.

“Balade de Bon Conseyl.” Also known as “Truth.” The most popular of Chaucer’s shorter works, preserved in no fewer than 23 manuscript copies. It opens by advising the reader to flee the crowd (at court?) and “dwell with sothfastnesse.” It consistently advises seeking a better life, and concludes with the tremendous line “And trouthe [thee] shal delivere, it is no drede.”

The Canterbury Tales. Now considered Chaucer’s master work, in which some thirty pilgrims preparing to visit the shrine of Thomas Becket at Canterbury meet at the Tabard Inn and are convinced by the Host, Harry Bailly, to journey together and tell tales on the way. The teller of the best tale, as judged by the Host, will receive a dinner at the Inn paid for by the other travelers. The book is prized because it contains not only the travelers’ tales but also an introduction describing the travelers themselves and links between the tales in which they argue, discuss, and offer opinions; it includes both the story of the journey and the tales told on the journey. The book was never finished; it was probably Chaucer’s last work, and he either died or gave it up before completing all the tales. As a result, we have only about two dozen tales, plus links for some but not all of them. The manuscripts do not agree on the order of the tales; there are ten different fragments which have been placed in many different arrangements. What is clear is that, after the General Prologue, the first tale was the Knight’s, followed by the Miller’s and Reeve’s, with the Parson’s Tale last, followed by Chaucer’s Retraction. The catalog below gives micro-summaries of the tales in the order most widely accepted by editors. Those dealt with extensively in this document are shown in bold.

• The Knight’s Tale. Palamon and Arcite fight over the hand of Emelye, with the gods seeing to it that Arcite wins the tournament, but dies afterward, leaving Emelye to Palamon.

• The Miller’s Tale. A fabliau, in which Nicholas and Absolon try to make love to Alisoun, the pretty wife of a foolish old carpenter. Most of the characters end up in an uncomfortable situation.

• The Reeve’s Tale. Another fabliau, intended to take revenge on the Miller; two clerks manage to sneak in and sleep with a miller’s wife and closely-watched daughter.

• The Cook’s Tale. A short fragment of what sounds like another dirty story, but Chaucer dropped it after only a few lines.

• The Man of Law’s Tale. The story of a young woman, Custace or Constance, whose faith repeatedly places her in danger but also saves her; she is twice set adrift but finally manages to come home safely to her true family.

• The Wife of Bath’s Tale. Another romance examined in this writing. An unnamed knight rapes a woman, is required to find out what women want, is forced to marry a hag to learn the answer, and when he gives her control over her destiny, is rewarded by her turning beautiful.

• The Friar’s Tale. An exemplum or lesson, but also an attack on the Summoner: A summoner meets a yeoman who is actually a devil. They travel together. The devil encounters various souls whom he cannot take — but at the end takes the evil summoner to hell.

• The Summoner’s Tale. The Summoner, angered by the Friar’s attack on his occupation, tells a tale of a Friar engaged in what amounts to extortion in the name of religion, mostly of one Thomas and his wife, with Thomas eventually “paying” the Friar by breaking wind.

• The Clerk’s Tale. Marquis Walter finds a low-born wife, Griselda, demands absolute obedience of her, subjects her to extreme testing, taking away her children and degrading her, and when she passes all his tests, finally accepts her again as his wife.

• The Merchant’s Tale. A lustful old man, January, uses his money to acquire a young wife, May. Unhappy with him, when he loses his sight, she takes Damian as a lover. He regains his sight even as May and Damian are making love, but May talks her way out of it.

• The Squire’s Tale. It appears that this was intended to be a fabulous — and extremely long — romance about the times of Cambyuscan (Genghis Khan). But after recounting many wonders and very little plot, the tale is halted. It is not clear if Chaucer abandoned it or if he intended the Franklin to interrupt it.

• The Franklin’s Tale. A Breton Lay of trouthe. Arveragus and Dorigen marry; Arveragus leaves Brittany. Aurelius courts Dorigen, who promises to accept him if he can clear the rocks from the shores of Brittany. Helped by a Clerk, he does. Arveragus tells Dorigen to keep her promise; Aurelius frees her of it; the Clerk frees Aurelius of his promise.

• The Physician’s Tale. Virginia, a beautiful Roman girl, finds an unjust judge trying to take advantage of her. Rather than lose her virtue, she has her father kill her.

• The Pardoner’s Tale. One of Chaucer’s greatest stories, even if its teller is utterly dishonest and greedy. Three drunks, seeing another man on his way to be buried, set out to kill Death. They meet an old man, who tells them where to find Death. His directions lead them to a treasure of gold, and the three kill each other. Find death they did indeed.

• The Shipman’s Tale. Probably an unrevised tale originally assigned to another teller, since the narrator seems to be a woman. A complex tale of a woman who does not love her husband and lures a monk into paying her for sex. The monk borrows the money from her husband; in a complicated way, everyone is paid back.

• The Prioress’s Tale. A “miracle of the Virgin”; a little boy sings constantly of the Virgin Mary. Murdered by Jews, he sings even after death, allowing his body to be found. The people take revenge on the Jews.

• Sir Thopas. Presented as Chaucer’s own first attempt at a tale, it is a spoof of the romance genre — a monotonous tale about a very ordinary knight who does nothing much. The tale is quickly interrupted by the Host, leaving Chaucer to instead tell…

• The Tale of Melibee. A prose tale; Melibee’s house is invaded, and he wishes his revenge, but his wife Prudence manages to talk him out of doing anything rash and guides him to understand forgiveness.

• The Monk’s Tale. Not, properly, a tale, but a series of very short examples of people raised and then cast down by fortune. It probably was in existence before the Canterbury Tales. It is sufficiently depressing and monotonous that the Knight finally asks the Monk to stop.

• The Nun’s Priest’s Tale. One of the most beloved tales, of the dream of the rooster Chauntecleer, who dreams of a fox without knowing what it is, argues with his hen Pertelote about it — then is seized by the fox and barely escapes with his life.

• The Second Nun’s Tale. A life of Saint Cecilia, in which she acts like a very pious busybody and ends up being martyred.

• The Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale. The Canon and his Yeoman join the party late; it appears they may be trying to cheat the pilgrims. The Canon soon retreats; the Yeoman goes on to talk about all the tricks and techniques of alchemy.

• The Manciple’s Tale. Phebus jealously kills his wife, then wishes he could bring her back to life, and takes away his white crow’s power of speech for trying to tell him the truth.

• The Parson’s Tale. Labelled as the final tale of the set, and linked directly with Chaucer’s final retraction, this is not a true tale but a prose exhortation. It is mostly about penance, and is not considered particularly interesting today.

“Chaucers Wordes unto Adam, His Owne Scriveyn.” Poem in which Chaucer complains about the poor quality of Adam’s copying. The date of the poem is uncertain; it exists in only two copies.

“Complaint to His Purse.” A short poem probably written, or at least rewritten, in 1400, after Henry IV usurped the throne of Richard II. It is a poem in rime royal appealing to the new king for the return of his income. (And Chaucer did eventually regain his pensions, but died soon after.)

“Complaint Unto Pity.” A complex poem of uncertain date, using intricate forms and legal language; it is a sad poem, with a complaint that pity is dead.

The House of Fame. Unfinished work. The date is uncertain; the best guess is that it is from around 1380. It uses octosyllabic couplets, a form which Chaucer later abandoned. It is a dream vision; the poet falls asleep, is caught up in a book (Virgil), then is carried into the heavens by a knowledgeable, talkative, boring eagle. He then sees goddess Fortune deciding whether to grant fame, and observes the House of Fame and the House of Rumour. At this point the poem breaks off.

“Lak of Stedfastnesse.” A short poem, of uncertain date, expressing wonder and sorrow at the fact that the world is “variable.” It has an envoy (to King Richard II, according to one major manuscript) appealing to him to lead the people back to steadfastness.

The Legend of Good Women. Other than the Canterbury Tales, probably Chaucer’s last major work, produced probably in the 1390s. It has been conjectured that Anne of Bohemia, Richard II’s first queen, requested that Chaucer write something to defend women who were constant in love. He never finished the work, writing only about half the number of tales he promised (those he completed are the legends of Cleopatra, Thisbe, Dido, Hypsipyle and Medea, Lucrece, Ariadne, Philomela, and Phyllis; the Legend of Hypermnestra breaks off probably just a few lines before its proper end). It does treat of women who were constant in love, but the telling is a little monotonous; Chaucer may have been relieved when Anne’s death in 1394 meant that he could give up the project. But the Legend is unusual in that Chaucer seems to have rewritten the prologue; there are two versions of it, known as “F” and “G,” perhaps from before and after Anne’s death.

“Lenvoy de Chaucer a Scogan.” A letter in verse, presumed to be to Henry Scogan, a fellow courtier and poet. In it, Chaucer light-heartedly accuses Scogan of being responsible for catastrophes and warns him of consequences; he also seems to ask for favors. A clever little piece which is perhaps most important for the insight it gives into Chaucer’s thinking.

“Merciles Beaute.” A short poem, known in only one copy, and that copy not attributed to Chaucer; the only reason to think it is his is the style. Chaucer claims to have escaped love, that merciless thing, and hopes not to go back.

The Parliament of Fowls. One of the few major works Chaucer actually completed. The poem is another of Chaucer’s dream visions. He is reading the Dream of Scipio, falls asleep, and finds himself being guided through the text — and then to Venus’s Temple, and then finally to a vision of the birds choosing mates on Valentine’s Day. This operates on many levels, with some birds much more “earthy” than others, but the main event is a contest of three male eagles to try to win the love of a female. This ends up being a formal debate which is not concluded; the decision is held off for a year while all the lesser birds go out and have fun breeding. As with much of Chaucer’s writing, the tone is light and the narrator is generally treated as something of a fool. The form is the rime royal, with which Chaucer had become very comfortable by this time (perhaps around 1380, although the dating is very uncertain).

Troilus and Criseyde. Chaucer’s longest completed work, his longest romance, and probably his last completed substantial project. It is thought to have been finished around 1386, shortly before he began the Canterbury Tales. The form is the seven-line rime royal stanza. It is the first major telling of the Troilus story in English, and the basic plot is familiar: Troilus, who had scorned love, is smitten when he sees Criseyde. Helped by his friend Pandarus, he and Criseyde form a liaison. But then she is traded to the Greeks for Antenor, and begins to pay attention to Diomedes, finally sending Troilus (who has been and will remain utterly faithful) a farewell by letter. He hopes to kill Diomedes, but is instead killed by Achilles. Because he has shown great trouthe, he is taken to a sort of pagan heaven. The story is the ultimate source for the tales of Shakespeare and others, but Chaucer’s stress is different; he does not condemn Criseyde although he admits that she will be condemned. Much of the tale is the result of the turning of fortune’s wheel. A tragic romance, many scholars regard it as Chaucer’s best work.

“Truth.” See “Balade de Bon Conseyl”

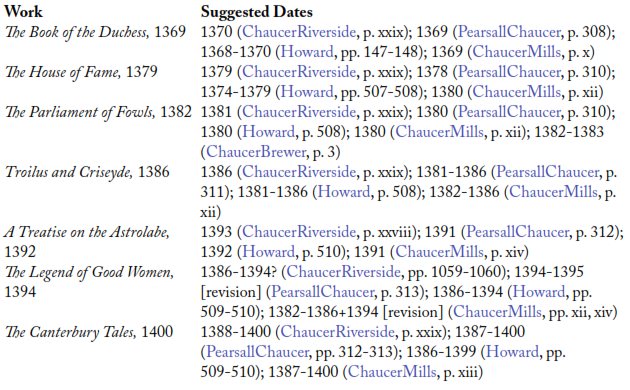

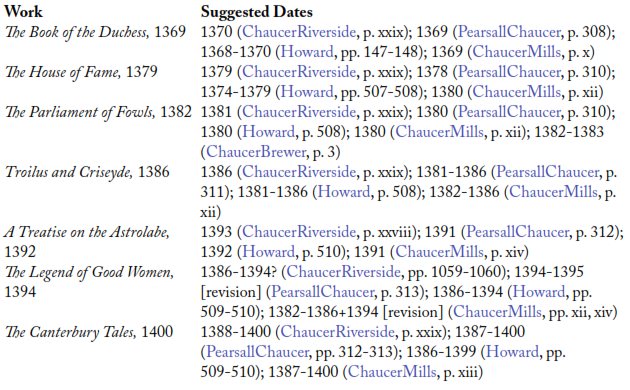

Approximate Chronology of Chaucer’s Major Works

Note: Most of the attributions below give approximate dates or date ranges; I have simplified to the central date in each source. If the date is a range, it should be taken to mean that Chaucer worked on the poem during all those years; if there is a single date, it is the date of completion. My personal summing up of the evidence of the date of completion is included in the left column; the sources for this opinion, in the right column.