Tunsia Campaign: Operation Vulcan

Operation Vulcan was to be the final “mopping up” of the German forces in North Africa. Rommel has been pushed from the East by the British and the west by the Americans. He had withdrawn to Tunisia with it short supply lines from Sicily. In the weeks before Operation Vulcan the German supplies had been restricted by the success of Operation Flax.

The British First Army commanded by Lieutenant-General Kenneth Anderson and reinforced by the British X Corps which was commanded by Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, was to take the lead, with the American II Corps under General Bradly, supporting. The objective of II Corps was to take Bizerte. It was this force that Carol Johnson accompanied.

The Germans were now commanded by General Hans-Jürgen von Arnim, not Rommel.

Though the Allies had many successes in the North Africa campaign, this all-out assault on Tunisia was not certain. Earlier, in this same area, the Allies suffered their worst defeat of the North African campaign, in the Battle of Kasserine Pass.

The Battle of Kasserine Pass

The Battle of Kasserine Pass took place during the Tunisia Campaign in February 1943. It was a counter-strike from German General Feldmarschall Erwin Rommel. The battle was the first big engagement between American and German forces in World War II.

In the Battle of El Alamein in August 1942, British General Bernard Montgomery pushed Rommel out of Egypt and into Tunisia. After taking several months to regroup, Rommel decided, in a bold move, to set his sights on Tunis, Tunisia’s capital, and a key strategic point for both Allied and Axis forces.

Rommel determined that the weakest point in the Allied defensive line was at the Kasserine Pass, a 2-mile-wide gap in Tunisia’s Dorsal Mountains, which was defended by American troops. His first strike was repulsed, but with tank reinforcements, Rommel broke through on February 20, inflicting devastating casualties on the U.S. forces. The Americans withdrew from their position, leaving behind most of their equipment. More than 1,000 American soldiers were killed, and hundreds more were taken prisoner. The United States had finally tasted defeat in battle.

The final tally reflected that the Allies suffered 10,000 casualties while the Axis suffered only 2,000; more than half of the Allied casualties were American.

The U.S. Army was really not ready to combat the Germans in tank warfare, being a latecomer to tank warfare, not fielding a mechanized armor corps until 1940. This lack of experience caused great losses in this first major tank battle.

The inexperienced and poorly led American troops suffered heavy casualties and were quickly pushed back over 50 miles from their positions west of Faid Pass. After the early defeat, elements of the US II Corps, reinforced by British reserves, rallied and held the exits through mountain passes in western Tunisia, defeating the Axis offensive. Rommel later had praise for how quickly the inexperienced American commanders learned from the early action in Kasserine, and improved their tactics by the end of the engagement.

After this battle, the Allied commander looked closely at the details of this defeat. It was seen that the failure to concentrate Allied armored units and integrate forces brought about the disintegration into disjointed and ineffective units

The U.S. Army instituted major changes in the organization of their forces, replacing a number of commanders. They also made changes in tactics. A big problem on the ground was that commanders allowed their units to separate, reducing their effectiveness. General Dwight D. Eisenhower began restructuring the Allied command. One big change was to bring in Major General George S. Patton to command II Corps. Allied commanders were given greater latitude to use their own initiative, to make decisions and to keep forces concentrated. Patton was not known for hesitancy and did not bother to request permission when taking action to support his command or other units requesting assistance. This is what was needed for the fast-moving tank warfare against Rommel and the Germans.

On March 9, 1943 Rommel returned to Germany to try to get Hitler to agree to move his forces from North Africa to defend Italy. Rommel was unsuccessful. He was placed on medical leave, on orders from Adolf Hitler, and command of North Africa was handed over to General Hans-Jürgen von Arnim. Rommel never returned to Africa. General Hans-Jürgen von Arnim surrendered to Allied forces two months later.

Operation Vulcan

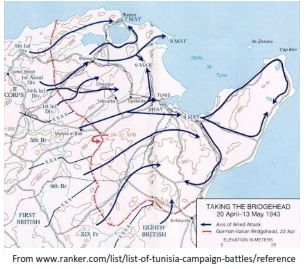

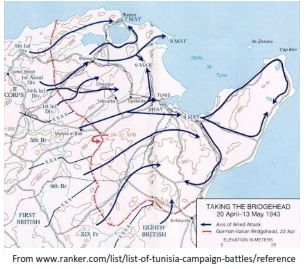

The orders for Operation Vulcan were issued on April 16, 1943. The British First Army would make the assault on Tunis, supported by X Corps of the British Eighth Army. The US II Corps would take Bizerte. The First Army would attack from the northeast. The Eighth Army and the French XIX Corps would be doing containment from the southeast. This is shown on the map below.

The British Eighth Army was going to attack in the area of Enfidaville region before the main attack This was a feint, to draw German troops away from area of the primary attack.

While the ground attack was being planned, so was the air assault. This would be carried out by the Northwest Africa Strategic Air Force, commanded by British Air Marshal Arthur Coningham. This force was made up of units from the British and US Air Forces. Since he had taking command mid-1941 he had turned it from an outgunned outfit to one that was achieving air superiority. One way he did this was by innovative tactics, like the use of fighter- bombers, able to fight as fighter planes in the air, or in bombing and strafing attacks of enemy ground targets. He also greatly improved the unit’s ground support, vital in the North Africa tank warfare. He recognized the importance of joint operations. The air power doctrine devised by Coningham is the basis of modern joint operations doctrine.

Coningham planned an all-out air assault, day and night, starting April 18th, against German airfields in Tunisia. They would also intercept transport aircraft on the way to Tunisia. Phase 2 was to start on April 22 to support the ground attack. Each morning at first light, reconnaissance bombers would make runs, to assess enemy position and to see if they had withdrawn. They would also bomb targets of opportunity. Continuous fighter ground attacks, and light bomber runs were to be made to assist the ground forces. He planned to use every aircraft available to attack the German forces during this operation; nothing was to be held in reserve.

Between April 17 and 23, they flew more than 5000 sorties and dropped 727,168 pounds of bombs. The air attack was so furious than the Germans withdrew most of their aircraft to Sicily and Italy, saving only a small force to protect Bizerte and Tunis. The Allies had established almost complete air superiority over Tunisia.

On April 22 the ground attack began when the British V Corps attacked north of Medjez el Bab. Allied intelligence estimated Axis troop strength to be 157,900. The British First Army and US II Corps slowly advanced toward Tunis and Bizerte, encountering stiff resistance, fighting for each hill and ridge. Hundreds of allied tanks were lost in the first two days. Most were knocked out by the heavily armored German “Tiger” tanks, a heavy tank that was the core of German tank units in North Africa. For this kind of tank warfare, the Tiger tank was a kind of German super weapon. In an early encounter with the Allies in Tunisia, eight rounds fired from a 75mm artillery gun simply bounced off of the side of the tank – from a distance of just 50 meters. The weight was a problem though. The heavy Tiger used a large amount of fuel, and had problems with some basic maneuverability, like crossing bridges. Tiger tanks also needed a high degree of support. Together these made for vulnerabilities.

Overall, the Tiger had a fearsome reputation. In Tunisia, they had a kill ratio of 18.8 enemy tanks for every Tiger lost. Against the Tiger many anti-tank tactics just did not work; the Tiger was so heavily armored. The Allies’ most successful anti-Tiger tactic in Tunisia was laying anti-tank mines guarded by antitank guns. When a Tiger was immobilized by a mine, antitank guns could take it out.

Tank Warfare

An important element of WWII tank warfare is that the US was really not ready for it. They didn’t start developing tanks until 1935, and when Pearl Harbor was bombed, had only a few built. They also believed that tanks were primarily weapons to overpower ground forces, and had no idea about tank warfare with other tanks. The Tiger was designed to fight other tanks. The US had no weapon, no tank, no anti-tank weapon, made for this purpose. And North Africa was the first major tank warfare in which the US engaged. There has been some light tank warfare in the Pacific theatre, but that is very different from the kind of massed tank battles that were in North Africa.

The US started WWII with the M2 Medium Tank, first produced in 1939. Only a few of these were ever built. Events in Europe made obvious that the M2 was obsolete, so upgraded equipment was designed. First was the M3 Stewart Light Tank, which added thicker armor, modified suspension and a 37 mm gun. Over 25,000 Stewarts were built. The M3 Stewart did so poorly in the Battle of Kaserine, that the allies stopped the use of light tanks in North Africa.

Next was the M3 Lee Medium Tank. designed in 1940. It was the main tank that the US started WWII with. A regiment of M3 Mediums was also used by the U.S. 1st Armored Division in North Africa. In the North African campaign, the M3 Lee was generally appreciated for its mechanical reliability, good armor and heavy firepower. It had problems, though. The tall silhouette and low, hull-mounted 75 mm were severe tactical drawbacks, since they prevented the tank from fighting from hull-down firing positions (where the body of the tank was protected behind a hill top, and the tank gun could fire over it). The use of riveted armor led to a problem called "spalling", whereby the impact of enemy shells would cause the rivets to break off and become projectiles inside the tank. Welding, instead of rivets, quickly became the standard, due to this.

The Lee was not satisfactory and was withdrawn from front line duty as soon as the M4 Sherman became available in large numbers. The M4 was the best known and most used American tank of World War II. The Sherman was a relatively inexpensive, easy to maintain and produce combat system, featuring a 75 mm main gun.

When the M4 Sherman tank went into combat in North Africa with the British Army at El Alamein in the autumn of 1942, it increased the advantage of Allied armor over German armor and was superior to the lighter German long-barrel 50 mm-gunned Panzer III and the howitzer-like, short-barrel 75 mm-gunned earliest examples of the Panzer IV. It was “good enough,” thought Allied commanders, and no more powerful tanks versions were developed in WW2. More than 40,000 M4 Shermans were build during WWII, with about half of them (20,361) going to US forces, 17,184 to the British, 4,102 to the Soviets., and 812 to China.

The Sherman first saw combat at the Second Battle of El Alamein in October 1942 with the British 8th Army. At the start of the offensive there were 252 tanks fit for action. First encounter with tanks was against