I was

with General Garcia for some weeks in the open and fertile district of the

Canto River, close to the Spanish towns of Jiguani and Bayamo. Extra outposts

were thrown out around camp, and from a neighbouring loma we frequently watched

the columns moving like light coloured snakes over the plain. We could see the

heliograph on El Galletta flashing instructions to the army in the field, and

thus every move was revealed to the Cubans, who knew the code.

At daybreak a party of rebel cavalry would

sally forth to skirmish, and the thunder of musketry would roll through the

trees for hours. At night the horsemen would return, muddy and bedraggled,

bringing in perhaps one man wounded, or reporting one killed. I witnessed

numerous skirmishes, afterwards locating the Spanish positions by piles of

cartridge cases almost uselessly expended, and invariably some Spanish graves.

In these so-called battles, the bushwhackers gained the advantage, and the

wretched Spanish boys wondered why their officers did not either rout the

enemy, or stay safely in the cities. Naturally they had little to gain, the

officers everything, in the faked Spanish victories that were daily cabled to

Madrid and foisted on the ever-hopeful Spaniards. The cross of San Fernando, so

liberally distributed by the Queen Regent as a reward for extraordinary

bravery, was seldom if ever deserved by the recipients; not that gallantry in

action was an unknown quality, but because the recommendation from the general

went usually to the highest bidder.

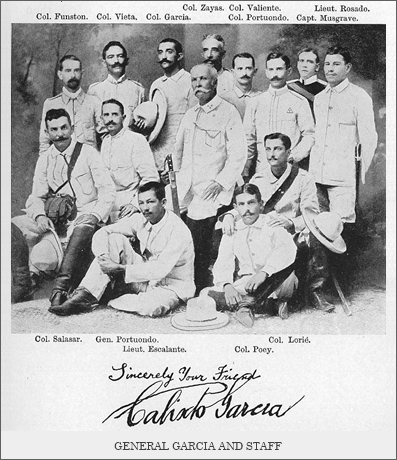

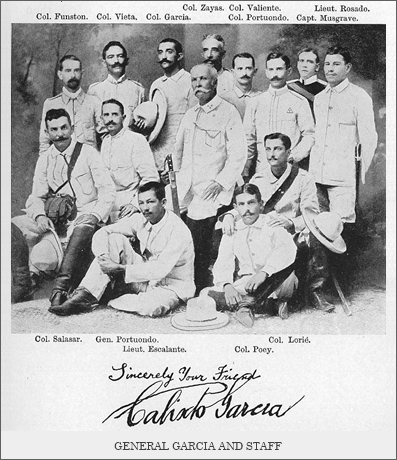

General Garcia had selected for his staff

chiefly officers educated in the States and I was honoured that, in recognition

of my part in freeing Evangelina Cisneros from the Recojidas in Havana; and to

afford me some semblance of authority, Garcia gave me a commission as Captain and

instructed me to carry despatches to the Americans in Santiago City. It was

deemed expedient for me to attempt to reach the capital with General Sanchez,

the brave and popular commander of the Barracoa district, and General Demetrius

Castillo, who was to assume command of the beleaguered districts of Santiago

City.

We left Garcia, who was preparing to oppose

the Spaniards with two thousand men, and made a forced march with two officers

of Castillo's command, hoping to pass round the enemy by night. A significant

heliograph message, however, announced that all operations were suspended, and

the column retired. Captain Maestre was sent forward with an escort to

accompany me through the dangerous San Luis

district, but he fell sick, and unwilling to delay, I pushed forward

alone with a servant and guide. Riding on the camino, we were held up by a

ferocious looking cavalry squad, apparently guerillas or bandits. Fight and

flight were impossible, and we fearfully threw up our hands, to discover that

our assailants were Cuban irregulars, searching for horse thieves.

At the zona I luckily met Preval, who had

just been to secure mail over the barricade at Santa Ana. Colonel Congera

selected guides and a fresh escort, and Preval agreed to accompany me over the

mountains. We found food very scarce in the mountains, unripe guava alone

sustaining us. It was bitterly cold also, especially at night, and the change

developed my latent malaria.

The people in the higher mountains were

half-barbarous, Indio-negroes, mixed descendants of those who had fled to the

hills to escape cruel taskmasters. Their patois was a curious conglomeration of

Spanish, Siboney, and French, and they held a precarious existence. They were

in sore straits then, but gave us advice, respect, and chocolate. We rode for

miles, continuously up and down, encountering no one save solitary sentinels

from the zona, perched on the rocks, watching the movement of the enemy in the

strongly invested Sant Ana valley. The Sierras del Cobre rise in vast ridges

abruptly from the sea, piled back peak on peak, their sides clothed with

impenetrable thicket, jagged with stupendous precipices of volcanic rock

overhanging the gloomy ravines far below.

At times

our trail led through narrow gorges, the rocks rising grimly in solid walls of

basalt and ironstone, while in the clefts grew orchids of the rarest kind;

veritable treasures for collectors, who can now make the ride. In many places

the soil was ferruginous and my compass was useless. The ruddy hue of the

ironstone formed a pleasing contrast with the rich emerald of the sparse grass

and luxuriant evergreen that filled the gorges; the scenery was magnificent,

but we paid little attention to the stupendous panorama at our feet. My mount

went dead lame; constant clambering over sharp stones, with precipitous trails

and even worse descents, had completely worn out his fore-hoofs. It was

impossible to halt, and by this time privations and lack of food had so told

upon us that we had not the strength to walk. Then his back gave out, and our

trip grew protracted, as I could only spur the faithful beast a few miles each

day.

The season of Las Luvias was over, but we

did not escape two frightful storms, during one of which, on March 17th, we

nearly lost our lives. It had been a bright day, but toward three o'clock when

crossing a most dangerous path high on the mountain-side, the sudden darkening

of the sky, and the exhalation of foetid miasma from the valley, foretold an

approaching temporal. The sky grew black as ink; we had no place for shelter,

and clung against the trail cut in the mountain-side, which rose like a wall

above, and dropped in a stupendous ravine below. When the tempest burst in all

its fury, we momentarily expected to be hurled into the abyss. The horses

snorted in terror, and reared and plunged on the ledge as we crouched beside

the rock, holding their bridles. The blackness increased, but the whole heavens

became suffused in light, the jet clouds rolled in flame while the rock

trembled with the frightful roar of thunder that followed. The scene was wild

and magnificent, the rushing wind tore up trees by the~ roots, and whirled them

over the peaks, great boulders crashed down, fortunately bounding over our

heads, but covering us in a shower of stones.

My escort, gigantic Negroes of the

mountains, lay on their faces, while the white sergeant prayed to the Virgin

for deliverance. Leaves, stones, branches, flew by us; thunder roared at brief intervals,

bursting, crashing, and re-echoing from peak to peak with the lurid flashes of

electric fluid that played around.

We were in, not under the storm, the black

clouds loomed on all sides, rolling together, wrestling and parting, and I

trust I may never again witness so magnificent, yet so frightful a spectacle.

Twice the earth quaked perceptibly, and a sulphurous smell almost overcame us.

The old craters and volcanic peaks seemed to belch fire and smoke as electric

clouds hung flaming from the summits. It was as if the seventh angel had

sounded, and the thunder and lightning and the great earthquake attending the

doom of Babylon had burst forth. We lay speechless with awe, and one realised

the infinite weakness and insignificance of mere man when confronted with the

stupendous power of the great Unknown. The impressions made upon me during that

storm will never be effaced.

The tempest died out as suddenly as it came,

and then we realised our cramped position, and crept painfully onward, our

faces bruised, chilled to the bone by our wet clothes. We descended next day

into the San Luis Valley, a pass leading into Santiago, and strongly invested

by the enemy. We fell in with a Negro Cuban guerilla and obtained a late and

unexpected supper. The rebels in reprisal were preparing to raid an adjoining

ingenio. I was too weak to ride out to the fight, but from the camp in the

foothills could see the brush. The engine-house was strongly invested and every

aperture belched fire. A candela soon lit up the scene, revealing the swarthy

faces of the Spaniards, and the black visages of their Negro assailants, for

save officers there were few white insurgents in Santiago.

Above the crash of rifles rose the rally “Viva

Espana!” mingled with “Viva Cuba y Maceo!” from the bronze-throated Orientals.

It was a weird scene, the outhouses were soon blazing, while the flames raced

over the cane-field like the surging of rushing water; from the villa rose the

frightened screams of women. But the Cuban fire soon slackened, and the fighters

came trotting back, reporting the gringoes too strong. They proudly exhibited

some prisoners of war, pacificos captured in the lodge, including the milkman

of the district. His cans were soon emptied down more needy throats, and the

men were liberated. Later three soldiers were brought in. The insurgents were

an irregular band, and fearing for the safety of the Spaniards, I hurried down

to see what could be done, but the rebels shared their supper with the

prisoners, and they were finally sent to Cambote.

Finding that we could not pass down the

valley to the city, we again took to the hills, crossing the Sierras Maestra,

rounding midway the Pico Turquino, over ten thousand feet above sea level. On

the Gran Piedra we were above the clouds, and while below the day was dull, our

eyes rested over an expanse of cloudland resembling snow-covered steppes, with

a glorious dome of sunlit sky overhead.

Passing down the mountain through the vapour

was extremely dangerous, and several times my horse jibbed, where the trail

gave sharp turns against the side of the rocky precipice. A false step meant

certain death, and the sure-footed Cuban mounts seemed bewildered by the mist.

A trooper ahead of me had much trouble with his steed. I warned him twice not

to use the spur, but his horse stopped dead and he gave it a vicious dig. The

frightened beast sprang forward, missed its footing, and horse and rider made a

mad plunge into space. Twice the poor fellow screamed, but his fall was

unbroken, and he was doubtlessly dead before he reached the gorge below.

Saddened with this disaster, sickened by hardships and difficulties, my nerve

gave out, and thanks only to Preval did we continue the march that day.

Our journey was tortuous but, at length, we

reached the Ojo del Toro, and finally sighted La Galleta, beyond which lay

Santiago City. On March 18th, after another frightful climb, we reached the

fringe of mountains on the coast. The sea rolled in, far below us, and from

that ridge, the most extensive view in the world, save the vista of Teneriffe,

can be obtained. Away to the south, shrouded in the sunlit haze of the

Caribbean, lay Jamaica; on the east, toward Maysi, glistened the Windward

Passage fringed by the southern Bahamas and Haiti. Westward, Santiago seemed a

city of Lilliput, nestling at the foot of the range. Two white gunboats, a Ward

liner, and the graceful “Purisima Concepcion” resembled four toy ships in a

midget harbour, while a tiny train steamed leisurely out by the head of the

bay. Beyond rose the opposite spur of the Sierras that extend to Manzanillo.

It took us many hours to descend to the

beach, and, in constant fear of discovery, we camped in an old coffee mill at

Las Guasimas. At daybreak we passed over the Jaragua iron district, owned by

the Carnagie Co. Though the insurgents had made no attempt to invest the coast

valley and foothills, everything was in ruins, and Weylerism was rampant in the

only district in east Cuba where there was positively no excuse for it.

Crossing by side trails, we passed the forts and gained the camino leading to

Caney. I left the escort near the Rio Aguadores, where we met an American

writer, who had just reached the manigua. Giving him my spare equipment, I rode

forward to reconnoitre the Spanish lines, and attempt to pass into Santiago

city.

Riding to a bank I was scanning the line of

wire and forts a mile beyond, when a clatter of hoofs on the road alarmed me. I

sprang into the saddle, and turned my horse toward the thicket; but the half-dead

steed staggered painfully, and ere I could urge it forward, a returning party

of guerilla cantered round the bend. The bewhiskered leader, who proved to be

Colonel Castelli, of Bourbon blood and bloody fame, yelled “Americano,

sirrinder!” as if proud of his English. I was paralyzed with terror. A

commissioned Captain, with government papers, and for the Yankees, would be no

mean capture; and the swarthy faces of these cut-throats, their grim smiles of

satisfaction as they drew their machetes and started toward me, and my

impending fate, were indelibly photographed on my mind in the brief second of

indecision that seemed an hour. Thrice I dug in my cruel spurs, until my

exhausted horse quivered with agony; then he stumbled painfully forward. I

could feel the machetes of my pursuers uplifted above me in my fright, and

flung myself from the saddle, only to realise that a barbed fence had checked

the enemy. Retarded by boots and spurs, winged by fear, I raced to cover as

they swarmed through the adjacent gap.

A carbine popped, then a revolver, and as I

ducked instinctively, I fell headlong, my satchel of papers flying from me; but

I was up and on again instantaneously, and plunged into the thicket. Crawling

far into the tangle, I could hear my assailants' voices as they peered into the

gaps. Fearful of shots from cover, Spaniards seldom ventured into woods. It was

also past their supper-time, and soon their guttural cursing was lost in the

distance. I ventured out just before sunset, and found some Cubans by the ford.

They stood over the body of my servant, who had gone for water to prepare grass

soup before I passed the lines. The poor youth had been captured by those

guerilla, and shockingly mutilated before death. His eyes were gouged out, his

teeth smashed, and the hacking of the body did not conceal the evidence of

unnatural torture that had been inflicted before death. It was too late for me

again to seek Preval, who died, poor fellow, from the hardships of the

campaign, two weeks after Santiago had fallen, and he had rejoined his

girl-wife to enjoy the freedom he had fought to achieve.

Hungry, faint-hearted, weary, and in an

indescribable state of mind, I directed the Cubans to bury the body, and turned

toward Santiago. Flanking San Juan, I succeeded in reaching a clump of trees

near the city outposts. Sentries were lazily pacing from fort to fort, the

evening gun was fired, its echoes reverberating in the hills, as Spain's banner

of blood and gold descended from the flagstaff and the buglers sounded the

nightly retreat. Officers came from the forts, the piquet and patrols were

mustered, and then, gradually, the stillness of night settled over the

community. In the Plaza, a stranded American merry-go-round wheezed out “Sweet

Rosie O' Grady” continuously, and my beating heart sounded louder than the base

drum accompanying the melody. Eight boomed from the cathedral, and the band of

the King's Battalion in the Square burst into “El Tambor Mayor.”

The suspense of waiting had been awful, but

it was now time to make my attempt to cross the lines. I crawled forward and

scaled the first barricade rapidly; the sentry there was chatting with the next

post, and I was soon against the wires, and between two forts that loomed up

fifty yards apart. The guards lounged round the campfires, cooking their “rancho”;

the sentinels whined out Alerta, and continued their chat, and, after vainly

trying to compose myself, I started over the barbed Trocha. The posts

fortunately protruded several inches above the wires, so, scaling the first

fence as a ladder, I was able to step across from strand to strand, grasping

each post firmly. Hearing a patrol approaching when all but over, I dropped

beneath the tangled meshes, soon to realise that in the night air of the

tropics hoof-beats are discernible at a great distance. My alarm was needless,

for ten minutes elapsed before the “rounds” of guards passed. Then I crawled

out, my hands and legs lacerated and bleeding; but I felt nothing of the barbs.

I was over, and content. The road to the city was clear at last.

It was almost midnight when I crept into

Santiago but, within minutes, I realised that I had to immediately leave again.

I made my way to a hotel on the wharf where the brothers Barella I knew were

good Cubans. They were effusive in welcoming me and, at great risk to their

lives, they said that I could stay for the night but that I must leave before

first light. The “Parisima Concepcion” fortunately was

in harbour, bound for Batabano and, through the good offices of Senor Barbosa,

the pilot, I was smuggled on board, and without ticket or permit left the port

that evening.

Senor Barbosa

related to me the events that had transpired in the past few days which, in

brief, were that, amid rising tension between Spain and America, the USS Maine

had been sent to Havana. This was seen as an insult to Spain's integrity and

led to the issue of a frenzied, soul-stirring manifesto broadcast throughout

the city. Such was the impact of this manifesto that the Insurgents had burnt

the Havana Bull Ring, but gay crowds had flocked over the ferries to the

"Plaza de los Toros" that day, and pointed derisively to the American

battleship, comparing it to their glorious equivalents: Pelayo, Carlos V., and

Viscaya. The carnival was at its height when a sudden column of flame shot

skywards, followed by a fearful explosion and a general shattering of glass in

the few buildings that required it in Havana. The Maine had been blown up with

the loss of the two officers and two hundred and sixty four Americans aboard

her.

There was a

general jubilation among the rabid Spaniards, and in one notorious restaurant

in Lamparilla Street, "Sopa del Maine" appeared on the menu for two

days, and the joke was thought exceedingly funny by the habitude.

After

landing at Batabano without difficulty, on March 28th, I hurried on to Havana,

fearing that it may already be too late to escape from the Island. My

despatches were now dangerously compromising; so I dropped off the train in the

suburbs, hoping to avoid the spies infesting the main depot.

War between Spain and American was now

certain and imminent and Havana was no longer safe. Americans were flocking

from the Capital and, along with all other foreigners in the city, I had to

formulate my plans for escape from the island. I considered, and rejected, both

the buying of a false passport, and swimming at night to a steamer in the

harbour. Colonel Decker, however, was at Key West with the despatch boat “Anita”

awaiting the advent of the fleet and, by underground mail, he arranged with me

to steam at night to the San Lazaro beach to pick me up. The attempt was to be

made on April 1st, but on the previous afternoon I lay resting in a secluded

room at El Pasage, sick, worn, and anxious to feel the security of American

soil again, when heavy footsteps broke my reverie, and a rough demand was made

at the door.

I glanced

hopelessly at the barred window, seized my revolver, only to realise the madness of resistance, and

hesitated, trembling, until a second thunderous demand nearly burst the door

from its hinges. Colonel Trujillo and his valiant myrmidons entered as if

bearding a tiger in his den when I withdrew the bar, but grew wondrous bold

when they found no resistance intended. Said the bewhiskered Trujillo, with a

malicious grin of recognition, and tone and manner suave, “General Blanco, sir,

wishes to hold conversation with you. To a gentleman as yourself it is needless

for me to say my sergeant is prepared for resistance; but a coach is in waiting

if you care to come quietly.” To the coach I went, as one in a dream, forgetting

that I was compounding the secrecy of my arrest by such surrender.