When we

first sighted Cuba, the sun was setting in tropical suddenness, like a globe of

fire extinguished in the sea. The declining rays, scintillating in multi-coloured

beams across the water, revealed a low-lying coast, fringed with palms and

backed by distant hills. Bathed in crimson light, the land appeared a paradise,

and it seemed impossible that in such magnificent setting a tragedy of two

nations was being enacted, and a whole people were writhing in the throes of

despair, oppression, and bloody death.

In speedy transformation, as the stage

limelight is shut off to turn the day scene to night, a black veil seemed drawn

across the heavens, and darkness supervened. A faint sprinkling of stars shone

feebly down, and then gradually the face of the heavens became bespangled with

constellations, and the luminous beauty of a clear night in the tropics was

revealed. On the distant coast lights flickered, while blazing above the

horizon rose the Southern Cross, typical of the sacred emblem to which the

struggling Cubans had so long appealed.

Suddenly a long beam of light quivered

across the sky and swept to right and left along the coast, and we were

awakened with a shock to the dangers of our enterprise. A Spanish warship was

watching for filibusters, and we well knew the summary justice meted out by

Spain to those taken in the act. We had left the Florida Keys in the tight

little schooner, but not as a regular expedition. Ostensibly on a fishing-trip,

we were carrying a few cases, stores, and ammunition to Pinar del Rio, where I

expected to effect a landing. We did not forget the “Virginius” massacre nor

the treatment of the “Competitor” crew. There was no distinction in those

precedents; sailor and Cuban, armed or unarmed, were treated alike, and our

faces blanched at the thought of capture. We sprang to the tell-tale boxes,

ready to hurl them overboard; but the cruiser held to her course, the blinding

glare still searching but never resting on our craft, and as the distance

widened between us we breathed more freely.

It was eight bells when we drew in near

shore and prepared to land just west of the Bahia Honda Point. Jose, the

practico, or guide, was a coal-black Negro born in slavery in Cuba, but he had

lived years in Jamaica, and proudly asserted he was an Englishman. As he spoke

both languages fairly, and knew western Cuba like a book, I gladly reciprocated

his assurances of friendship and brotherhood, and a true friend did he

ultimately prove. He had piloted the ship to a nicety, and after the cases had

been handed over to the gig, we took our seats and rowed silently ashore.

A flash and loud boom to westward forced us

to ply our oars rapidly, and at first we thought the ship was discovered.

Probably it was the night gun from the warship in the Bay, for nothing

transpired to confirm our fears. We ran into a sandbank and, braving sharks,

were forced to drop over and haul the boat across; but finally, wet and tired,

we had everything on shore. The boat returned to the ship, and Jose and I

struck out for the interior, to find a Cuban camp and warn the guardia costa of

our advent.

I was in no enviable frame of mind when we

plunged into the bush. This was a venture of my own choosing; but I had heard

stories of these Cuban insurgents, “Negro and half-bred cutthroats, a scum

gathered for loot, murder, and robbery, under the guise of patriotism,” said my

Spanish friends, and even allowing for their prejudice, I was extremely

apprehensive. “Would they steal my effects? How would they treat me? Probably

my good clothes would excite cupidity, and they would hang me as a spy to

legalise the murder. It had been done in Central America, and why not here?”

Such were the forebodings that flashed before me that night, for of the Cuban

question I was absolutely ignorant. Far from civilization, in darkest Africa, I

had not been aware of a Cuban revolution until reaching the Canary Islands.

Here I saw weedy conscripts dragged from sunny valleys and driven to the

transports for Cuba, their arms shipped on separate vessels to prevent mutiny.

Weeping mothers told in awed whispers of their boys murdered by these ferocious

insurgents, whom, in their misled innocence, they believed to be fiends

incarnate; and even the kindly old Commandant of Las Palmas told me such a

history of the ungrateful colonists that my sympathies were awakened for Spain.

When Canovas, in his leonine power, issued his fiat, “last peseta, last man,”

before he would grant reforms to the island, she had shipped an army of 200,000

men across the Atlantic. In proud assent the Spanish nation continued to expend

blood and treasure, though the result was as water poured on the Sahara.

After describing the raising and equipment

of the conscript hordes in Spain, I was asked simultaneously by the editors of

a London daily and a review to outline the military situation and method of

warfare in Cuba. Such a mission guaranteed interest and adventure, and finding

that under no circumstances could I join the Spanish forces in the field, I was

now en route for the insurgents. I had been warned previously that even if the

rebels did not eat me - for the ignorant Spaniard even credits them with

cannibalism - I must expect no quarter if captured by the Imperial troops, so

enraged were they against the insurgents and those who cast in their lot with

them.

Jose and I marched painfully up a rocky

track in the darkness, stumbling at every step. From the row of forts around

Bahia Honda rose the shrill “Alerta!” of successive sentries, a few campfires

gleamed fitfully in the distance, and tolls of the cracked bell of the little

chapel, merry laughter, and the strains of a hand-organ in the city were wafted

over on the still night air. Around us all was silent as death. “Alto! Quien

va?” came the sudden challenge. “Cuba!” responded Jose, with alacrity; and in a

moment two dark figures sprang at him. My revolver was out in an instant, but

they were only embracing my guide and vigorously patting him on the back, a

mark of deepest affection among the Cubans. The two sentinels brought their

horses from the field, and courteously insisted that 1 should mount, while one

rode forward to apprise the camp of our arrival and send men to the beach for

the stores.

I was loath to rob the soldier of his horse;

but he insisted, marching ahead on foot, and cautioning us to keep absolute

silence. I scrambled into the saddle, and we jogged along for perhaps a league,

when we reached the Cuban outposts. Round the campfires were grouped

picturesque-looking bandits, Negroes to a man. By the flickering light they did

not look prepossessing, but they greeted me effusively, and gave me a palm leaf

shelter to sleep under. Being worn out, I gladly crawled in, and keeping my

revolver handy, was soon asleep.

A hand on my shoulder, a strange voice - the

robbers, I thought. I sprang up only to be blinded by brilliant sunlight, to

find a ragged “asistente” had brought a cup of delicious coffee, and stood

grinning at my confusion. Jose came soon after, and said we must be moving, for

we were too near the city for safety, and I found the outpost had waited an

hour rather than wake me. The officer, a commandante or major, was a half-caste

named Gonzales, and through the medium of Jose, he welcomed me to Cuba Libre,

adding that General Rivera would be glad to see me. He was sorry he had no

breakfast then to offer, but the Spaniards had been very bad there and nothing

was left in the country. Later, however, we would reach a prefectura and

perhaps find food. He insisted on my keeping my mount, and the owner thereof

tramped along gaily, telling me he, his house, his horse, and his all, were at

my service. These rebels were certainly interesting fellows, and apprehensions

as to my reception soon vanished.

Crossing hills and skirting woods, we reached

a wilder district and finally the insurgent camp. The colonel was a black of

gigantic proportions, with one of the finest faces I have ever seen. His

features were small and regular, of the Arab or Houssa rather than the Negro

type. He was a veteran of the ten years' war, bore numerous wounds, and was one

of the most trusted officers in the brigade of General Ducasse. His manly

bearing was impressive, and he neither boasted of his prowess nor related

horrible massacres by the Spaniards that could not be verified - two common

failings in west Cuba.

I had been sitting in camp but a few minutes

when I was addressed in perfect English, and met my first white rebel

gentleman. Major Hernandez by name, a graduate of an American college and a law

student. He explained that he was on a commission and had stayed in camp for

the night.

Friendships ripen quickly under such

circumstances, and we were soon exchanging confidences. In half an hour I had

received some new ideas of the Cuban revolution. “Todo mambi negro,” laughed my

friend, “just here and in some other places, yes, but members of the best white

families in Cuba are in the woods.” And as I talked with that young patriot who

had given up a good home and pleasant surroundings for a rough life of danger

and privation, I began to realise there was something in the cause of Cuba Libre.

I had been given to understand that no white colonists of repute, no true

Cubans were engaged in the uprising, that it was simply an extensive

brigandage, a western “Francatripa” or “Cincearotti.” How soon I found it was

the whole Cuban race writhing and struggling against a fifteenth century

system!

The winter campaign of '96 was just closing,

and the insurgent army of the West was never in a worse condition. Antonio

Maceo had been killed but a few days previously, and the province was flooded

with guerillas, and soldiers flushed with this success. Rivera crossed the

Mariel Trocha early in December, and was in command near Artemisa, toward which

Hernandez was going. I was anxious to accompany him, but he persuaded me

against it, pointing out the innumerable dangers and hardships of travelling

poorly mounted through a district so strongly invested by the enemy. He advised

me to go to a certain prefectura in the hills, where I could secure a guide and

good horses, and join some force when things grew more settled. There were a

few Americans in Pinar del Rio, he said, two correspondents, and some

artillerymen. I met but one, some time later, a man named Jones, in the last

stages of consumption; the correspondents, Scovel and Rea, had gone to visit

Gomez. I reluctantly said farewell to Hernandez, and later reached the

prefectura.

The prefect was a white man of considerable

intelligence, a guajiro, or farmer. His house had been destroyed by Maceo's

order, to prevent its conversion into a fort, and the Spaniards had looted his

cattle; but with true Cuban philosophy he explained that boniatos (sweet

potatoes) were easy to raise, and when Cuba was free all again would be well.

His residence was now in the hills near La Isabella, a mere bohio of clay,

thatched with palm. In the deep gorges below, the Guardia Civil, the local

guerilla, and sometimes columns operated, but fearing ambuscades, the hilly

trails were usually given a wide berth by the Spanish regulars. To the west lay

the fertile valley of La Palma, now simply a blackened desert right up to Pinar

del Rio City. The valleys to the south were in even a worse condition; many

residences had been destroyed by Maceo, and later Weyler with his columns had

swept the country with fire and sword until it was a desert of ashes.

I had a sharp attack of fever in the

prefect's house, and was exceedingly well treated. When, after several days'

hospitality, I moved on, he was grossly insulted because I offered him money.

Many days had passed uneventfully in the district. I rode around occasionally,

but in the valley the columns were operating, and guerilla raids took place too

close to us to be pleasant. I had a narrow escape one day, several shots being

fired after me by a marauding party, and I soon witnessed many phases of the

horrible warfare Spain was waging. No important insurgent force came in our

district, only small rebel bands; and becoming impatient we finally marched

across country toward the Trocha, a mule having been secured for Jose and my

own sorry steed exchanged advantageously.

After crossing the hills to the once

glorious valley to the south, Weyler's brutal measures were in evidence on

every side. Following Maceo's death, he had redoubled his efforts to subdue

Pinar del Rio, and each day we came across smouldering houses, rotting

carcasses of cattle, wantonly slaughtered, and blackened stalks of burnt crops.

For miles we rode without meeting a living soul; but later, striking the woods

again, we found Cuban families camped in the thickets, subsisting on roots, and

living in constant terror of the guerilla. These cut-throats raided and looted

at pleasure, driving into town the fugitives they captured, killing the men and

frequently outraging women.

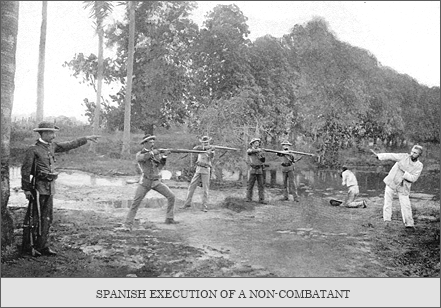

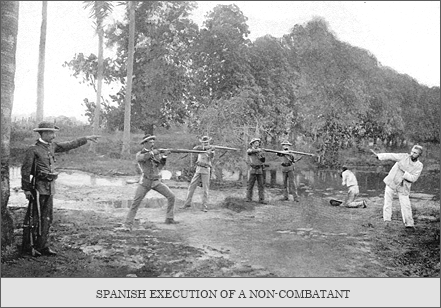

Raid

followed raid, the pacificos, or non-combatants, being ruthlessly slaughtered

if captured too far from the town for convenient transportation, or upon

attempting to escape from the soldiery. Five miles from Mariel, not twenty feet

from the camino Real (Royal highroad), the bodies of two women and four men,

all killed by the local guerilla, lay for three weeks unburied, and probably

the remains are there yet. In the hills just north of Candelaria I was shown

the ruins of a field hospital, and the charred remains of sick men, butchered

and burned therein. Later, in the main road near Artemisa, we found the body of

an aged pacifico, his head split in twain with a machete. Sylvester Scovel, who

had spent weeks in the province before I landed, personally investigated the

cases of over two hundred non-combatants murdered by Weyler's orders, in Pinar

del Rio. This was but a fraction of the atrocities, and from the bodies I

actually saw, and the cases brought to my notice in a regular journey through

this district, I have no hesitation in saying that I believe Scovel's

investigations to be correct, regardless of the attempts of others to impugn

his veracity in these reports.

Exaggerated stories of Spanish atrocities

have flooded the American press, until responsible persons are inclined to

doubt the authenticity of every case ' reported; but in those early weeks I saw

evidences of sickening horrors that turned me from a strong sympathiser with

Spain to a bitter hater of everything connected with her brutal rule in Cuba.

True, I also heard and verified stories of oppression and cruelty by individual

insurgents in Pinar del Rio, notably of one Bermudez, a blackguard given a

command by Maceo when officers were scarce. He, a Cuban, instituted a reign of

terror in his district, equalled only by Weyler's rule. But Bermudez was soon

disgraced, and finally hanged by Gomez, while the butchers in Spanish uniform

were but obeying Weyler's implicit orders by the perpetration of outrages.

A number of desperadoes had joined the

insurrection for loot, and in the rich West, Gomez and Maceo found constant

crimes and other lawless acts committed by their followers, that terrorised the

pacific Cubans. False leaders arose, and by carrying on a war of rapine under

the guise of patriotism, greatly damaged the Cuban cause. These men were dubbed

plateados, or plated Cubans; and Gomez for many weeks warred only against them,

hanging some convicted of flagrant outrage. So severe were the measures

instituted by the old leader, that men were executed for petty theft, and false

patriots deserted in dozens.

Several miscreants in Pinar del Rio, under

Burmudez, and Colonel Murgado, who had also obtained a regular commission, were

simply brigands. When Maceo broke up the gang, most of them reached Havana, and

re-enlisted in the Spanish guerilla, where they could loot at will without the

risk of being hung. Maceo then put his personal friend, the brave young

Ducasse, in command of the perturbed district, and he gradually won back the

confidence of the distracted pacificos.

Another colonel, named Nunez, was deprived

of command and reduced to asistente rank for executing five Spanish cavalrymen

whom he declared were caught burning a house. Lieutenant Castillo and Prefect

Gonzales were shot for looting. These severe examples had a salutary effect

upon the insurgent army. Gomez claimed that a revolution that became a refuge

for those who wished conveniently to follow criminal and disorderly lives would

not be justified, even for the cause of liberty. With such in their ranks, the

Cuban cry, “Viva nuestra bandera sin mancha” (Long live our unstained banner),

would be of nil effect. The insurgent forces were composed of all classes and

shades of society; once wealthy planters, farmers, farm labourers, and ignorant

negroes from the cane fields formed the bulk of the Army of Deliverance,

students from Havana College, clerks, cigar makers, and a tatterdemalion scum

from the slums adding a considerable contingent from the cities. Diverse as

were these elements of the revolution, they were but local factors in the

universal struggle of mankind for emancipation from the dominant creed, “Might

is Right.”

As the revolution gathered wider support, trade

was brought to a standstill, and the enraged Spaniards in Havana, who naturally

suffered loss of spoil, demanded that Premier Canovas should despatch a man to

Cuba who would stamp out the rebellion at all costs. Campos had dared to

suggest that genuine reforms would alone restore peace, but to this they would

not listen. The old cry, “No quarter,” was raised, and to satisfy the frenzy General

Weyler was appointed.

Valeriano Weyler was but General of

Cataluna, but he had the reputation of being absolutely unscrupulous, and was

thus the man for Cuba. When he arrived in Havana, the intransigents tendered

him an effusive welcome, especially the volunteers. Raising his effeminate and

neatly gloved hand as he harangued the populace, he announced that Spain's

enemies would find his hand gloved with steel. He came to make a pitiless war

upon them, and pledged himself to speedily restore peace to the island.

His first policy was to strengthen the

Trochas, or fortified barricades, one built across the narrow portion of the

island from Mariel to the south coast, the other across Puerto Principe from

Jucaro to Moron. Thus he hoped to shut Maceo in Pinar del Rio, Gomez in the

Central provinces, the forces under Jose Maceo in the extreme east, and deal

with each in turn. The Cubans showed their contempt by cutting their way through

the Trochas repeatedly, though the barriers certainly hindered easy and

frequent communication.

All cities and towns of consequence, and the

railroad tracks, were fortified. Reinforcements also poured over from Spain,

thousands of wretched conscripts being torn from their homes and shipped to

Cuba. They were equipped with Mauser rifles, the most effective extant, and

abundant ammunition; but the absolute lack of commissary, their cotton uniform

and canvas shoes with hemp soles, the ignorance of the officers, and lack of

drill, made the vast army so hurriedly mobilised, useless for extensile

operations. It was effective, however, for Weyler's purpose of devastation, and

the disintegrated duty in the thousands of small wooden block-houses that

surrounded the towns and guarded all the railways in the island, with the aid

of barbed-wire barricades built from fort to fort. Weyler soon had 200,000

so-called regulars in Cuba; 25,000 guerillas were also raised, chiefly from Negroes

and half-breed scum in the cities, and freed criminals with previous military

experience from Spain. The Spanish volunteer organization throughout the island

was 60,000 strong. This gave a command of at least 285,000 men.

It has been easy for writers to criticise

Weyler as a brutal plunderer, who cared for nothing but blood and corruption.

Brute he was, corrupt and absolutely unscrupulous, but he was by no means the

sensual monster represented. His orders were explicit; to crush out the

rebellion at, any cost and regardless of human sacrifice, and he accomplished

wonders. His policy was extermination, and he neither denied nor cloaked it.

His administrative ability was stupendous. With inadequate means at his

disposal, he cut up the island in fortified sections, scattered part of his vast

army as “beaters in,” while with the remainder he attempted to kill off the

hedged-in coveys in succession. He filled his own pockets, and those of his

officers; yet gave his vast army enough food to keep them alive, subservient,

and in some semblance of health, when food itself was terribly scarce. He

planned and effectively carried out his extermination, murdering hundreds of

insurgents and their sympathisers in cold blood, and starving to death

thousands of innocents, whose nature and dearest associations had made rebels

at heart. But for the marked steadfastness of the Cubans, their resolution to

accomplish or die, and the influence of some of their leaders, Weyler could

have crushed the revolution by force. Eventually he would assuredly have

crushed it by extermination if Spain's finances could have sustained him.

In October 1896 all plans of the campaign

were formulated, and on the 21st the following order was issued from the

Governor's Palace, Havana, and spread broadcast throughout the country:

- - -

I, Don Valeriano Weyler Nicolau,

Marquis of Teneriffe, Governor-General, Captain-General of this Island,

Commander-in-Chief of the Army, hereby order and command:

1. That all the inhabitants of the

country districts, or those who reside outside the lines of fortifications of

the towns, shall within eight days enter such towns occupied by the troops. Any

individual found beyond the lines at the expiration of this period shall be

considered a rebel, and dealt with as such.

2. The transport of food from the

towns, and the carrying of food from place to place by sea or land, without a

signed permit of the authorities, is positively forbidden. All who infringe

this order will be tried as aiders and abettors of the rebellion.

3. The owners of cattle must drive their

herds to the towns, or their immediate vicinity, where guard is provided.

4. The period of eight days will be

reckoned in each district, from the day of publication of this proclamation in

the chief town in that district. At its expiration all insurgents who present

themselves to me will be placed under my orders as to residence. If they

furnish me with news that can be used to advantage against the enemy, it will

serve as a recommendation also the

desertion to our lines with firearms, and more especially when insurgents

present themselves in numbers.

Valeriano

Weyler. Havana, October 21st, 1896.

- - -

This was

the initiation of his policy. Article 1 stamped the bando as worse than

Valmaseda's proclamation of '69. The latter stipulated that men only should be

treated as rebels, i.e., shot at sight; and the United States loudly protested.

In '96 Weyler brazenly applied the same order universally; but the Washington

Administration allowed such enforcement within seventy-eight miles of America's

coasts without protest until too late.

The execution of Weyler's order commenced in

Pinar del Rio. Immense columns of troops poured into the province, and operated

in sections, driving the people from their homes, and looting and burning the

houses of high and lowly. When the eight days of grace expired, all excesses

were tolerated. Stock was seized, crops were torn up and destroyed, cattle that

could not be eaten or conveniently driven off were wantonly slaughtered; even

the long grass was burned to make the country uninhabitable for the rebels.

Weyler had drawn lines which prevented the

easy mobilisation of the scattered insurgent commands. Gomez had returned to

Santa Clara, cartridges were scarce, and against so large an army Maceo and his

small force could now only harass the enemy, and were powerless to prevent the

great devastation. On the approach of the soldiers, many of the people fled in

terror to the woods. Here the guerillas distinguished themselves by routing out

the fugitives, hunting them like wild beasts with dogs (this 1 have personally

witnessed), and frequently forcing into their camps such comely women as they

could capture. If towns were handy, the terrified pacificos were bundled in

unceremoniously; if not, the machete terribly and effectively cleared the

country, though better fate a thousand times to be butchered in cold blood, and

devoured by vultures and wild dogs, than to be slowly starved to death in the

reconcentration quarter of the towns, and the younger women forced into

degradation.

When Weyler's fiat was rigidly enforced near

the Mariel Trocha, consternation fell on the inhabitants of the other sections

of the West. In anticipation of a similar visitation, the panic-stricken people

hurriedly made their decision. The men foresaw compulsory service with the

Spaniards in the cities, and though until then they had no thought of joining

the rebels, it was now the only alternative. The women, children, and old men,

carrying their portable possessions, wended their way to the nearest township before

the soldiers arrived to loot. The men gathered their livestock, took what food

they could, and marched off to the hills to join their insurgent brothers. The

order had the same effect in Havana, Matanzas, and Santa Clara provinces.

Within three months it had driven the male strength of the island and an

abundance of food to the insurgent ranks.

By Christmas of '96 Pinar del Rio was burned

up completely, Havana Province was undergoing , the same drastic treatment, and

Captain-Gent3ral Weyler cabled to Madrid that the West was thoroughly pacified.

The rebels had only withdrawn to the mountains; and when the Spaniards

evacuated one district, the Cubans moved in, leaving their base of supplies in

the hills. Dumped by thousands in small towns, with the surrounding country a

waste, the herded reconcentrados abjectly starved from the first. Weyler had

destroyed their homes and crops, knowing full well the inevitable result.

“This is war,” was his naive reply to either

question or remonstrance on the subject.