XIX

SUMMER'S FAREWELL

The Blaze of Its Adieu to Mount Washington

Summer lingers yet just south of Mount Washington and, though often frowned away, as often returns to say good-bye, "parting is such sweet sorrow." Already there have been days when the frown was deep, when the hoar frost on the summit clung as white as snow in the sun and refused to melt even on the southerly slopes, when at night the cold of winter bit deep and the Lakes of the Clouds shone wan in the morning light under a coating of new, black ice. Then summer has come back, dissolving the repentant frost into tears at a touch of warm lips, bending and quivering over the great gray dome of the summit until, approaching from peaks to the southward, I have seen her presence surround all in a shimmering enfolding of loving radiance.

From the high ridge of Boott's Spur I saw it thus, slipping back myself to say good-bye, of a day in late September. From no point in the mountains does one get a finer impression of the massive dignity of Washington summit than from this. The Spur is itself no mean mountain, rising with precipitous abruptness from between Tuckerman Ravine and the Gulf of Slides, bounding in rounding, thousand-foot ledges from Pinkham Notch to a height of more than 5500 feet; it lifts the persistent climber to a veritable mizzen-top whence he looks still upward to the main truck of the summit, with the wonderful rock rift of Tuckerman Ravine between, dropping out of sight behind sheer cliffs at his feet. On such an autumn day there is a mighty exhilaration in thus floating in blue sky on such a pinnacle. The body is conscious that the spirit within it steps forth from peak to peak into limitless space and is ready to shout with the joy of it. Indian summer, which does not come down to the sea-coast levels for another month, touches the high ranges now, and under its magic they remember spring. It paints the brown grasses, the sedges and the leaves of the three-toothed cinquefoil which scantily streak the cone of Washington, with a purple tint, and the gray rocks themselves ripen like grapes with a soft blue bloom in all shadows.

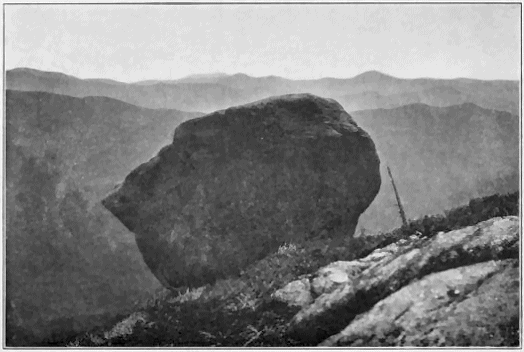

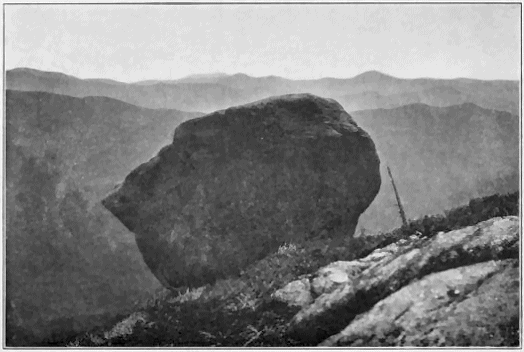

To me the finest of the four trails which lead to the summit of Boott's Spur is that which comes up from Pinkham Notch by way of the Glen boulder. Its start is through a forest primeval. The lumbermen have taken the spruce, to be sure, but here are birches along the footpath that may have been growing when Darby Field first came this way to the summit of Washington with his two Indians. It may be not. Birches are quick-growing trees, yet here are some that are almost three feet in diameter, having the great solid trunks and shaggy, scant heads of foliage which are characteristic of trees that reach maturity in a forest before it knows the axe. Whatever the trials of the trail it is worth while to climb among such trees as these. It is a steep trail, in ledgy spots, and it soon leads to slopes where the axe has not followed the spruce, on to a growth which the axe scorns, and on again to a dwarf tangle of firs that are hardly to be passed without the cutting of a canyon. Not in the mangroves of Gulf swamps nor in the rhododendron "slicks" of the southern Appalachians can a traveller find a more determinedly dense impediment to his passage than in these mountain firs where they dwindle to chin height and interlace their century-old stubs of branches. Farther up they shorten into a knee-deep carpet which hardly delays the passage, and from these emerges the great cliff on whose verge hangs "the boulder."

He who does not believe that "there were giants in those days," that they fought on the Presidential Range, and that the head of one, cut off and petrified with fear, rolled down to this spot where it quite miraculously stopped, has probably never seen the boulder from the ledge about north of its point of poise. There it looks all these things. It has a George Washington nose, a Booker Washington chin, and the low forehead of the cave man. It has even an ear, plugged with a bluish, slaty rock quite different from the brown sandstone of which the whole is composed, as this is quite different from the various rocks of the ledges round about. Motorists driving up the Glen road can see the boulder ahead of them outlined against the sky. It looks from that point as if it might roll down and stop the car at any time. But if it looks insecure in its position to motorists in the highway, to the Alpinist who stands beside it this appearance of instability is startling. Jocund day never poised more on tiptoe on the misty mountain top than does this big rock head on the verge of the cliff. I, for one, dislike to go directly below it. Some day it is going to roll on down the mountain and that might be the day.

In the clearness of the autumn air all the forest of Pinkham Notch and its approaches lay far below my feet. The world below was a Scotch plaid of equally proportioned crimson and green with a finer stripe of rich yellow. Every maple is at the height of its flame, but the birches of the valley still hold much of their green, at least from above. Below them in the forest one walks as if at the bottom of a sea of golden light in which flecks of other color fall or spring into view at each new turn of the path. The hay-scented ferns are almost as white as the bark of the canoe birches. The brakes are a golden brown, and all the under-forest world is yellow with the leaves of all varieties of birch. Only the withe-rod sets splotches of maroon in its great oval leaves, and shows among them its deep blue of clustered berries. But none of this reaches my eye as I sit high in air above it. Thence the world below is a Scotch plaid, out of which the roar of Glen Ellis Falls rises, the falls themselves completely hidden within the plaid.

"The Glen Boulder has a George Washington nose, a Booker Washington chin, and the low forehead of the cave man"

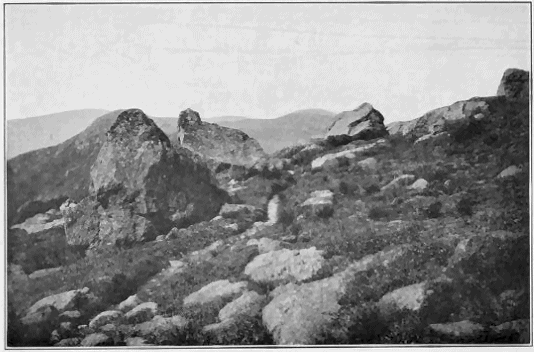

More and more of the under-world of birch yellow comes to the surface as the trees climb the hill till at the last they spread a golden mist of color wonderful to behold. At certain portions of the slope the firs begin again and go on up the hill with the birches, slender and beautiful, aspiring and inspiring, and even along among the bleak rocks they creep, soft green mats of spreading limbs, flecked here and there with the yellow of creeping birches and the maroon of low blueberries, all this patterned among the exquisite lichen-grays of the rocks. All the southerly ridge beyond the boulder is a rolling smoke of these golden birch tops pricked through with the green-black spires of spruce and fir, nor has any slope on any mountain more beauty to offer to the eye on this day in late September when the air is like a crystal lens through which one looks into unmeasured distances and sees clearly.

Behind the boulder, terrace by terrace, the mountain rises to the top of Slide Peak, whence one may see the magic of the air lenses change this mingling of vivid colors to a blend which is a rich violet and loses its red as the distance grows greater till it ends on the far horizon in a pure blue that seems born of the very sky itself, and to sleep in its arms. With it the eye floats over the ranges that rim the horizon half around, touching and soaring from Wildcat and Black on to Baldface and on again to be lost in the maze of hills that ride eastward into the dim distance of the State of Maine. More to the southward Doublehead lifts his twin peaks in massive dignity and over Thorn is Kearsarge, almost airy in the contrast of its perfect cone. On again southeast and south flash lakes, Silver and Conway and Ossipee, Lovell's Pond and in the far distance Sebago, lighting the softest blue toward a haze that one suspects is the sea. Due south between peak after peak, between Paugus and Chocorua and through a gap in the Ossipee Range lie the waters of Winnipesaukee, shining beneath the noonday sun.

The Gulf of Slides beneath my feet was a vast bowl of russet gold decorated with Chinese patterns of deep green. In its very bottom I saw a black stream rounding the edge of a level open meadow where the deep grass had been trodden into paths by the passing deer. All round about it the spruce and firs set a bristling wall of pointed tops, and the quivering air that filled the bowl to the brim was obviously a liquid. I could see it flow up and over the ridge toward the summit of Boott's Spur, and as if to prove that it did so a red-tailed hawk flapped up from the firs that surround the little meadow, caught the updrift of this southerly breeze and soared on it in easy spirals to a point just above the ridge. Here he caught another current that came up the Rocky Branch Valley, a breeze resinous with the last big area of spruce in sight from the summits near Mount Washington, pungent with the smoke of the great woodcutter camps in its midst, and soared on up Boott's Spur. And as he did so the sun flashed back in white fire from a point in a ledge of the Spur overhanging the Gulf of Slides.

Somewhere in the highest hills hung once the great carbuncle whose fame led many early settlers to dare disaster in mountain searches for precious gems. Tradition has it that the great gem vanished from its matrix long ago. Perhaps it did. But something flashes white fire from a high cliff on the Spur to the eye of him who gets the sun at just the right angle from Slide Peak. The carbuncle may be there yet. Certainly the ridge that leads up from the boulder is rich in matrices for gems. Out through its granite burst veins of sparkling quartz, dazzling white, pink and green. Imbedded in this quartz are great crystals of silvery mica and smaller ones of black tourmaline. There are spots along the trail that glitter like a Bowery jeweller's window. This profusion of gemlike stones is to be found all along the way to the high ridge of Boott's Spur and make it doubly fascinating. If the great carbuncle ever really hung high in the mountains I fancy it is still not far from this neighborhood. Very likely it broke from its cliff and lies now buried in the débris of slides at the bottom of the great precipice which springs from the Gulf up to the top of the Spur, leaving only a fragment to dazzle my eyes from the top of Slide Peak. Perhaps the real thing is there yet, and I recommend the Glen Boulder trail to present-day gem hunters.

But from the mountain tops on the last days of September all the world is one of gems. From Washington the range and the Southern peaks which rise from it showed ruby fires of sunlight transmitted by the colored leaves of creeping blueberries and the three-toothed cinquefoil. Lower, emerald and bloodstone glinted among the dwarf firs, and lower yet were zones of gold for the setting of as many gems as the forest could furnish. All the blue stones of the lapidary showed their colors in the distance while the woods of the lower slopes were chrysoprase, garnets, topaz and all other stones which hold red, yellow or green glints in their hearts. Looking westward only the centre of the Fabyan plateau lacked this plaiding of interwoven gem colors. Instead it was a level oasis of tender green around which sat the great hotels in solemn sanctity.

The perfect clearness of this still mountain air was not only for the sight but for the hearing. One's ear seemed to become a wireless telephone receiver and sounds from great distances were plainly audible. Voices of other climbers, I do not know how far away, seemed to come out of the ledges of the high ridge of Boott's Spur as I sat among them and looked toward the great gray summit of Washington. Among the Derryveagh Mountains in the northwest of Ireland I have heard voices of children at play a mile away come out of a fairy rath, or seem to come out of it, and here at far higher levels was a similar spell at work. Finally I located other voices, seeing people on the summit of Monroe and others down at the refuge hut near the Lake of the Clouds, talking to one another. That one party could hear the other at that distance was strange enough, but that I, a mile farther away than the people at the hut, could hear those on top of Monroe was a still greater proof of the wonderful clearness of the air at that time.

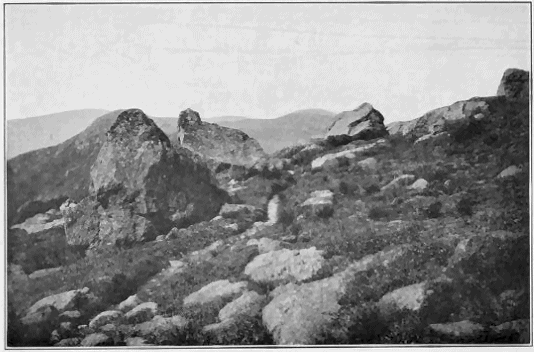

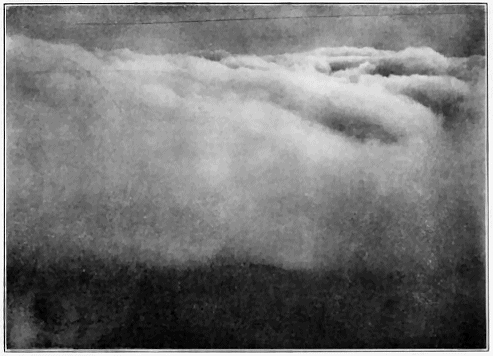

The Crawford trail along Franklin, Mount Pleasant in the distance

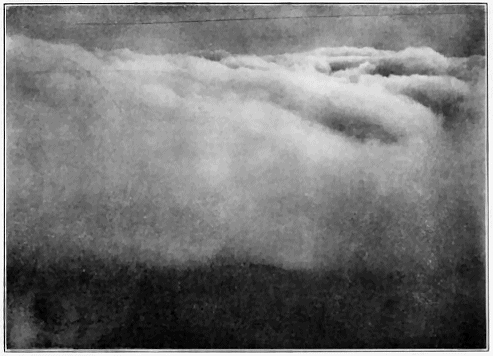

Such a condition presages storm, and before night, from the summit of Washington, I watched it materialize from thin air. In the sunlit stillness a thin, long line of cumulo-stratus clouds appeared circling the southern horizon from west to east. The line was broken in many places and it was lower than the summit, for I could see clear sky and land through the breaks. It did not seem possible that such a line of disconnected clouds could bring storm. But they joined and thickened while I watched, and by and by, as if at a word of command, far to the south light scuds were detached from them and came scurrying in from beyond Chocorua, blotting out Tremont and Haystack, Bear and Moat, swallowing the Montalban Range and Rocky Branch ridge in their floating fluff, coasting up and over Boott's Spur and blotting out Tuckerman's Ravine. They whirled in upon us, palpable, cotton-batting clouds with a chill in their touch, and wrapped all the summit in gray obscurity.

Again and again they broke and let me see all about, and each time I saw that the ring of cumulo-stratus clouds was denser at the bottom, and had moved in towards us from all the southern half of the horizon. The sun set, but we did not see it. The world was blotted out in a gray mass of scudding vapor that gradually became black night, out of which by and by rain came hissing on a wind that shook the buildings of the tiny summit village beneath their clanking chains. Morning came, and noon of the next day. The wind had changed from south to northwest, the sky in all valleys was clear, but still the dense clouds swirled about the cone of Washington and swathed the high ridge of the whole Presidential Range in masses of fleeting mist. No rain fell from this, but to stand in it was to gather and condense it in the pores of one's garments and become wringing wet.

"The world was blotted out in a gray mass of scudding vapor that gradually became black night out of which by and by rain came hissing"

Feeling my way through this opaque blindness down the painted trail to Tuckerman Ravine, I was well down to the verge of the head wall before I could see below it. There the wind seems to make a funnel between the Lion's Head and Boott's Spur and draw the clouds through it so rapidly as to thin them. With the Fall of a Thousand Streams splashing all about me, I saw the gray masses lift and through them the sun pouring its autumn gold upon the plaid of Pinkham Notch. The ravine below me was in shadow, but the fairy gold of that light seemed to flood back into it and infuse all its dripping firs and wet rocks with rainbow colors. It decked this mighty chasm in the mightiest mountain as if for a bridal, and all along the downward trail by the rushing Cutler River the firs shed diamonds and rubies with each touch of the wind, and the birches, yellow and black and white, held their autumn gold encrusted with precious stones.

In such guise was the mountain decked for my farewell to it, and though the slanting sun shone warm on the Glen road when I reached it I was wet with the parting tears into which all this finery dissolved as I passed. The summit is lone now. The last train has taken the villagers to the base and the village is boarded up. The hoar frost whitens it as I write and the film of ice dulls the clear eyes of the Lakes of the Clouds. Soon the snow will begin again to blow over the head wall into Tuckerman Ravine and mass at the bottom into the glacier which will once more stretch broad across the ravine next spring. Already the crimson of the rock maples which flames the woodland begins to sift down and leave the topmost twigs bare. Summer has said good-bye to the summit, and though she looks often fondly back she is well on her way south through the valleys.

END