IN THE WHITE WOODS

THE snow came out of the north at a temperature of only twenty degrees above zero, yet, strange to say, for some hours it came damp and froze immediately on every tree-trunk or twig that it struck. The temperature remained the same all day and through the night, but the streak of soft weather somewhere up above which was responsible for the damp snow soon passed away and frozen crystals sifted down that had in them no suspicion of moisture. Yet these tangled tips with those already frozen firmly to the trees, and made a wonderful snow growth the whole woodland through. The next morning it hung there untouched in the crystal stillness and as the woodland people waked they might well have rubbed their eyes, for they had found a new world.

It was a mystical white world that had crowded in and mocked the slender growth of all trees and shrubs with swollen facsimiles in white. The northerly side of tree-trunks, large or small, showed no longer gray bark or brown, rough or smooth. Instead, fluffy white boles rose from the white ground and divided into white limbs, which separated again into mighty twigs of white. The dark outlines of bare trees, the delicate tracery of gray and black that massed day before yesterday in the exquisite dark shades of the winter woods, existed only as a faint definition of the world of whiteness which had descended upon us in a night.

Upon each shrub and tree had grown another, its fellow in exact reproduction of line and curve, only swollen to forty times the size. This enormity of limb and twig shut off all vistas. Where it had been easy to see through the bare wood, the brush merely latticing your view and softening up the middle distance with gray or pink or brown, according to the growth, now the gaze was tangled in a narrow grotto heavily decorated with buttress and baluster, with fluting, frieze, and fillet, with mantel, moulding, mullion, and machicolation, and beat in vain against a solid wall of alabaster just beyond. The greater pines were pointed cones of white, each limb drooping with the weight of snow to its fellow below, and the hangings of the outer tips joining to form a surface wherein miniature domes, set strangely askew, yet massed in curves of superb beauty to the making of the symmetrical whole.

In it all there was no feeling of weight. As a matter of fact it pressed the smaller shrubs and trees well down toward earth. The narrow woodland path was barred with a woven portcullis of white that had swung down from either side. Here and there in the open the smaller pasture cedars were bowed to the ground, doing reverence to the garment of mystic purity with which the earth was sanctified as if for the passing of the grail. In a moment you expected to see some Galahad rise from his knees with shining face, take horse beneath the marble towers of this woodland Camelot, and ride down white lanes in holy quest. In the deep wood the seedling pines broke through the drifts like gnomes from mines of alabaster, whimsical green faces showing beneath grotesque caps and shoulder capes that were part of the whelming snow. Yet it all looked as light and airy as any structure of the imagination, seeming as if it might rise and float away with a change of mood, some substance of which air castles are built, some great white dream poised to drift lightly into the realm of the remembered, as white dreams do.

In woodland pathways where the trees were large enough on either side so that they did not bend beneath the snow and obstruct, all passage was noiseless; amongst shrubs and slender saplings it was almost impossible. The bent withes hobbled you, caught you breast high and hurled you back with elastic but unyielding force, throttled you and drowned you in avalanches of smothering white. To attempt to penetrate the thicket was like plunging into soft drifts where in the blinding white twilight you found yourself inexplicably held back by steel-like but invisible bonds, drifts where you felt the shivery touch of the cold fingers of winter magic changing you into a veritable snow man, and as such you emerged. It was more than baptism, it was total immersion, you were initiated into the order of the white woods and not even your heel was vulnerable.

Thus panoplied in white magic, my snowshoes making no sound on the fluffy floor of woodland paths, I felt that I might stalk invisible and unheeded in the wilderness world. The fern-seed of frost fronds had fallen upon my head in fairy grottos built by magic in a night. These had not been there before, they would not be there to-morrow. To-morrow, too, the magic might be gone, but for to-day I was to feel the chill joy of it.

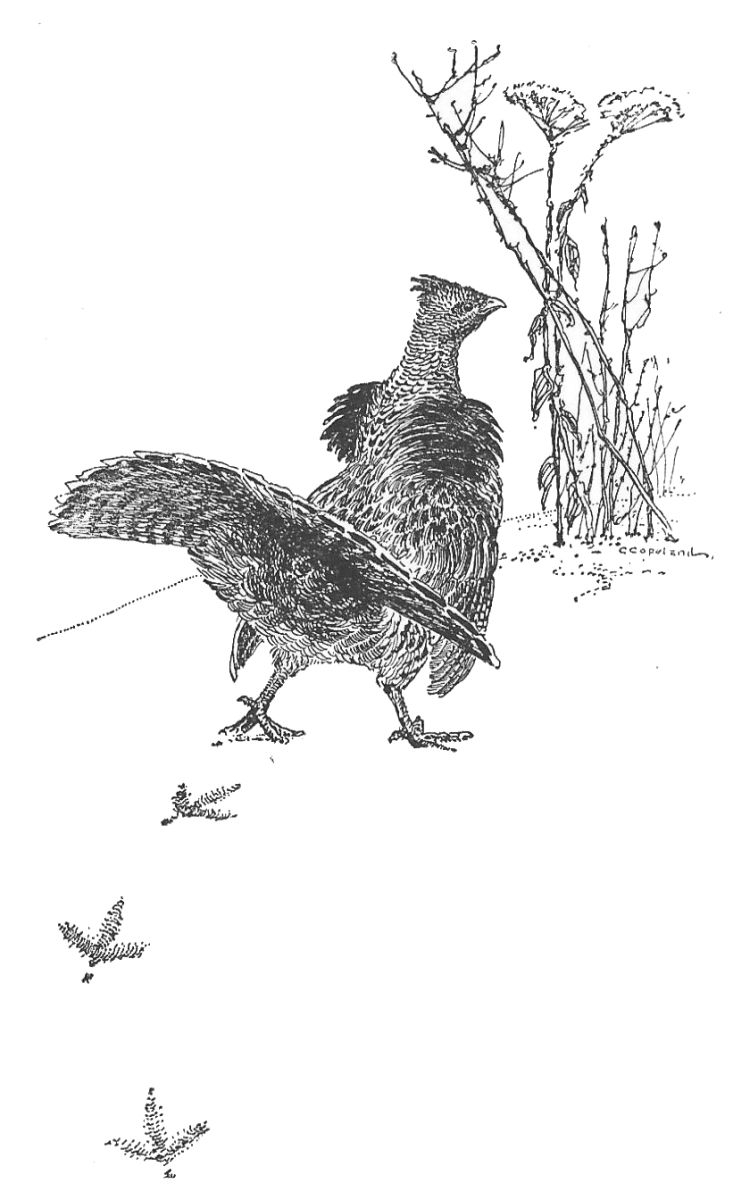

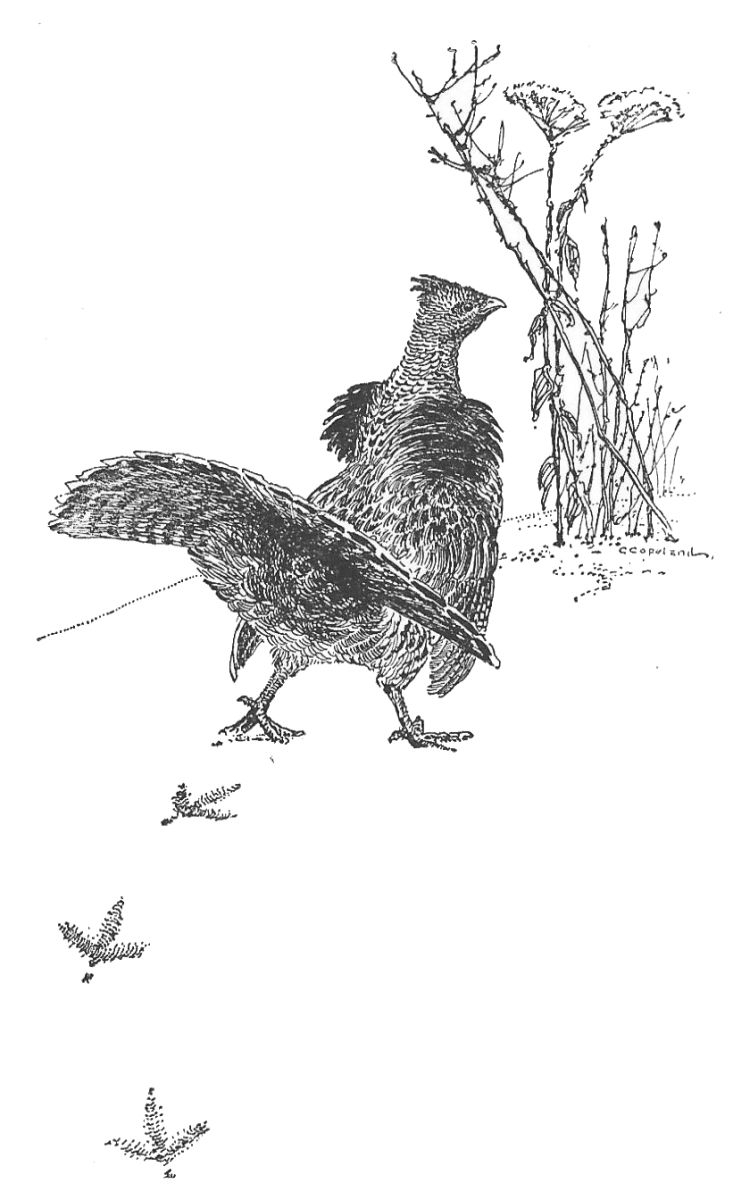

A ruffed grouse was the first woodland creature not to see me. I stalked around a white corner almost upon him and stood poised while he continued to weave his starry necklaces of footprints in festoons about the butts of scrubby oaks and wild-cherry shrubs. He too was barred from the denser tangle which he might wish to penetrate. He did not seem to be seeking food. Seemingly there was nothing under the scrub oaks that he could get. It was more as if, having breakfasted well, he now walked in meditation for a little, before starting in on the serious business of the day. He too was wearing his snowshoes, and they held him up in the soft snow fully as well as mine supported me. His feet that had been bare in autumn now had grown quills which helped support his weight but did not take away from the clean-cut, star-shaped impression of the toes. Rather they made lesser points between these four greater ones and added to the star-like appearance of the tracks.

I knew him for a male bird by the broad tufts of glossy black feathers with which his neck was adorned. It was the first week in February, but then Saint Valentine’s day comes on the fourteenth, and on this day, as all folklore—which right or wrong we must perforce believe—informs us, the birds choose their mates. My cock partridge must have been planning a love sonnet, weaving rhymes as he wove his trail in rhythmic curves that coquetted with one another as rhymes do. His head nodded the rhythm as his feet fell in the proper places. Now and then he bent forward in his walk as one does in deep meditation. If he had hands they would have been clasped behind his back when in this attitude, as his wings were. Again he lifted his head high, fluffed out those glossy black neck feathers and strutted. Here surely was a fine phrase that would reach the waiting heart of that mottled brown hen that was now quietly keeping by herself in some secluded corner of the wood. The thought threw out his chest, and those tail feathers that had folded slimly as he walked in pensive meditation spread and cocked fan-shaped. I half expected him to open his strong, pointed bill and gobble as a turkey does under similar circumstances. The demure placing of star after star in that necklace trail was broken by a little fantastic pas seul, from which he dropped suddenly on both feet, vaulted into the air, and whirred away down arcades of snowy whiteness and vanished. I don’t think he saw me. He was rushing to find the lady and recite that poem to her before he forgot it.

He lifted his head high, fluffed out those glossy black neck feathers and strutted

On the white page of the path that lay open under groined arches of alabaster no foot had written a record for many rods, then it seemed as if from side to side stretched a highway. Back and forth in straight lines had gone a creature that made a lovely decorative pattern of a trail, a straight line firmly drawn as if with a stylus, on either side at a distance say of three-fourths of an inch tiny footmarks just opposite each other, while alternating with these and nearer the middle line were fainter and finer footprints.

Here the tiny deer-mouse had drawn his long tail through the snow, whisking from stump to stump in a quiver of excitement lest an enemy gobble him up, shooting across like a gray shuttle weaving this exquisite pattern that is like that of a dainty embroidery on a lady’s collar. How he can gallop so regularly and make his tail mark so straight is more than I can tell. Indeed, so sly he is and so swiftly does he go that I have never seen him make it. Beside this tiny pattern the marks where the gray squirrel has leaped across are like those of an hippopotamus on a rampage and the print of my own snowshoe was as if there had been a catastrophe and a section of the sky had fallen.

Along with the tiny mouse tracks were those of our least squirrel, the chipmunk. There is no difficulty about seeing him. He will almost come if you whistle for him. If you will camp near his burrow you may teach him to come and eat nuts out of your hand, answering any prearranged signal, such as whacking them together or chirping to him.

Even though you are a total stranger he will not hesitate to whisk out of his hole under the brush heap right in your face and eyes, whisking back again in great terror, no doubt, but immediately putting out his whiskered nose to sniff and wrinkle it in comical confusion, half friendly, half frightened. So I had but to wait a moment before little Tamias striatus was out from under the brush pile and had flipped over to a fallen log, ploughing the soft snow off the end of it in a comically frantic rush to his hole there, the entrance being snowed up. He was in and out again in a jiffy, standing on his hind legs and peering over the log and making noses at me, jumping to the top and whirling and jumping down again, and then flashing out and kicking up crystals in a rush across the road to another hole under another brush pile, his scantily furred half tail erect and as humorously vivacious as everything else about him. The chipmunk when he thinks he is going to be captured and is filled with great fear—half of it being, I believe, fear that he wont be—is the most delightfully comical little chap that grows in the woods. If he’d only keep as wild as that after he is tamed I’d like one for a pet.

He was in and out again in a jiffy

Down in the open meadow where the unfrozen brook ran black in its banks of snow, touched only here and there with the green of luxuriant watercress, I found the trail of the crows. Not one was in sight and there was no sound from them anywhere. It was as if the snow had covered them under and they were unable to break through it. Here, however, was evidence to the contrary. Surely they had breakfasted, and no doubt well. They had marched all up and down the low banks, and where a snowy island lay in midstream they had promenaded it from one end to the other. Here and there I could see where they had stepped into shallow water and waded. The marks of muddy claws in the white snow were much in evidence where they had jumped out again. Just as summer bathers “tread for quahaugs” in the summer shallows south of the cape, I could fancy them feeling with their toes for shell-fish and prodding for them with long bill when found. But they had had a salad, too, with breakfast. I could see where they had pulled out the watercress all along and cropped it down to the larger stems. Even in winter weather when the snow lies deep the crow knows where to find what is good for him.

Where the path wound round the brow of the hill and the birches stand, their granaries still full of manna for the wandering bird, it seemed again as if my plunge into the white thicket had baptized me with invisibility. Of a sudden the air was full of the sound of wings and a flock of tree sparrows that must have numbered hundreds swung about my head and charged the snow-covered birches. Their dash shook some snow off and a few lighted, the others swinging off and having at them again. This time all found a footing and began to feed eagerly on the seeds from the tiny cones, scattering the birdlike scales in flocks far greater than their own.

I had stopped stock-still at the sound of their wings, and they took no more notice of me than if I had been a snowed-up fence post or a pasture cedar. I tried to count them, but it was not easy. They seemed to twinkle from twig to twig like wavelets in the sun, and though their garb is sober their movements dazzle. Just as I would get a group on a single tree nicely tallied they flashed as one bird over to another tree, and mingling with their fellows there spoiled the count. I finally estimated, rather roughly, that there were three hundred of them, a half of a light brigade of as merry fellows as I wish to meet. They twittered jovially and musically among themselves, and now and then one essayed a little sotto voce song which he never could finish because immediately his mouth was full.

Once or twice some inaudible order seemed to thrill through the flock and they whirled upward as if a single muscle moved every wing, swung a short ellipse and lighted again, often in the same trees. As they worked into the birches almost over my very head I could see every marking on them; the black mandibles, the lower yellowish at the base, the reddish brown crown and the back streaked with the same color, with black, and a yellowish buff, the wing coverts tipped with white and the grayish white breast with what looks like an indistinct dark spot in the center. In a kaleidoscopic flock of three hundred or more it is not easy to give every bird even a passing glance, but I am quite sure there were other than tree sparrows present. I seemed to see birds without the faint dark spot in the breast. A few, I know, had a distinctly rufous tint there, and I fancy swamp sparrows, a few of which winter hereabouts, and perhaps other birds for sociability’s sake, were with my winter chippies.

The shaking of the snow from the trees and their gleaning among the birch cones had scattered the little seeds which they love so well all about on the snow and soon they followed them. The surface a little before had been white. Before the birds were ready to come down it was spiced so liberally with the seeds and scales that they had shaken down that it was the color of cinnamon. Then with one motion the flock dropped like autumn leaves and began a most systematic seed hunt in which they left no bit of the space unsought. Yet when they were gone you would hardly find two tracks that crossed; they hopped in winding parallels that never went over the same ground a second time, leaving figures much like the mazes which schoolboys of long ago used to draw on their slates. They came almost to my feet and I was beginning to feel that my fancy of invisibility was very real after all when with a twitter of alarm and a single united action they whirred into the air and vanished over the treetops.

I turned away in chagrin. The magic was destroyed, evidently, and in turning I saw the cause. Just behind me in the snow with quivering tail and green eyes glaring accusingly was the family cat. He was hunting far from home, but I saw contemptuous recognition in his eyes and I knew he was thinking that here was that great, clumsy creature that was always scaring away his game.