CERTAIN WHITE-FACED HORNETS

THE lonesomest spot in all the pasture, the one which the winter has made most vacant of all, is the corner where hangs the great gray nest of the white-faced hornets. Its door stands hospitably open but it is no longer thronged with burly burghers roaring to and fro on business that cannot wait. It was wide enough for half a dozen to go and come at the same time, yet they used to jostle one another continually in this entrance, so great was the throng of workers and so vigorous the energy that burbled within them. While the warm sun of an August day shines a white-faced hornet is as full of pent forces, striving continually to burst him, as a steam fire-engine is when the city is going up in flame and smoke and the fire chief is shouting orders through the megaphone and the engineer is jumping her for the honor of the department and the safety of the community. He burbles and bumps and buzzes and bursts, almost, in just the same way.

It is no wonder that people misunderstand such roaring energy, driving home sometimes too fine a point, and speak of Vespa maculata and his near of kin the yellow jackets, and even the polite and retiring common black wasp, with dislike. In this the genial Ettrick Shepherd, high priest of the good will of the open world, does him, I think, much wrong. “O’ a’ God’s creatures the wasp,” he says, “is the only one that is eternally out of temper. There’s nae sic thing as pleasing him.”

This opinion is so universal that there is little use in trying to controvert it, and yet these white-faced hornets which I have known, if not closely, at least on terms of neighborliness, do not seem to merit this opprobrium. That they are hasty I do not deny. They certainly brook no interference with their right to a home and the bringing up of the family. But I do not call that a sign of ill temper; I think it is patriotism.

Probably the trouble with most of us is that we have happened to come into quite literal contact with white-face after the fashion of one of the early explorers of the country about Massachusetts Bay. Obadiah Turner, the English explorer and journalist, thus chronicles the adventure in the quaint phraseology of the year 1629.

“Ye godlie and prudent captain of ye occasion did, for a time, sit on ye stumpe in pleasante moode. Presentlie all were hurried together in great alarum to witness ye strange doing of ye goode olde man. Uttering a lustie screme he bounded from ye stumpe and they, coming upp, did descrie him jumping aboute in ye oddest manner. And he did lykwise puff and blow his mouthe and roll uppe his eyes in ye most distressful waye.

“All were greatlie moved and did loudlie beg of him to advertise them whereof he was afflicted in so sore a manner, and presentlie, he pointing to his foreheade, they did spy there a small red spot and swelling. Then did they begin to think yt what had happened to him was this, yt some pestigeous scorpion or flying devil had bitten him. Presentlie ye paine much abating he saide yt as he sat on ye stumpe he did spye upon ye branch of a tree what to him seemed a large fruite, ye like of wch he had never before seen, being much in size and shape like ye heade of a man, and having a gray rinde, wch as he deemed, betokened ripenesse. There being so manie new and luscious fruites discovered in this fayer lande none coulde know ye whole of them. And, he said, his eyes did much rejoice at ye sight.

“Seizing a stone he hurled ye same thereat, thinking to bring yt to ye grounde. But not taking faire aime he onlie hit ye branch whereon hung ye fruit. Ye jarr was not enow to shake down ye same but there issued from yt, as from a nest, divers little winged scorpions, mch in size like ye large fenn flies on ye marshe landes of olde England. And one of them, bounding against hys forehead did give in an instant a most terrible stinge, whereof came ye horrible paine and agonie of wch he cried out.”

Let go on the even tenor of his home-building and home-keeping way, white-face is another creature. One of his kind used to make trips to and from my tent all one summer, and we got to be good neighbors. At first I viewed him with distrust and was inclined to do him harm, but he dodged my blow and without deigning to notice it landed plump on a house-fly that was rubbing his forelegs together in congratulatory manner on the tent roof. He had been mingling with germs of superior standing, without doubt, this house-fly, but his happiness over the success of the event was of brief duration. There came from his wings just one tenuous screech of alarm followed by an ominous silence of as brief duration. Then came the deep roar of the hornet’s propellers as he rounded the curve through the tent door and gave her full-speed ahead on the home road. An hour later he was with me again, had captured another fly almost immediately, and was off. He came again, many times a day, and day after day, till I began to know him well and follow his flights with the interest of an old friend.

He never bothered me or anyone else. He had no time for men; the capture of house-flies was his vocation and it demanded all his energy and attention. In fact that he might succeed it was necessary that he should put his whole soul into earnest endeavor, for he was not particularly well equipped for his work. He had neither speed nor agility as compared with his quarry, and if house-flies can hear and know what is after them, the roar of his machinery, even at slowest speed, must have given them ample warning. It was like a freighter seeking to capture torpedo boats. They could turn in a circle of a third the radius of his and could fly three miles to his one, yet he was never a minute in getting one.

I think they simply took him for an enlarged edition of their own kind and never knew the difference until his mandibles gripped them. He used to go bumbling and butting about the tent in a near-sighted excitement that was humorous to the onlooker. He didn’t know a fly from a hole in the tentpole, and there was a tack in the ridgepole whose head he captured in exultation and let go in a sort of slow wonder every time he came in. He got to know me as part of the scenery and didn’t mind lighting on top of my head in his quest, and he never thought of stinging me. I timed his visits one sunny, still day and found that he arrived once in forty seconds. But this was only under most favorable weather conditions. A cloud over the sun delayed him and in wet weather he was never to be seen.

His method with the fly in hand was direct and effective. The first buzz was followed by the snip-snip of his shear-like maxillaries. You could hear the sound and immediately see the gauzy wings flutter slowly to the tent floor. If the fly kicked much his legs went in the same way. Then white-face took a firmer grip on his prize and was off with him to the nest. The bee line is spoken of as a model of mathematical directness, but the laden bee seeking the hive makes no straighter course than did my hornet to his nest in the berry bush down in the pasture.

Flies were plentiful and, knowing how many hornets there are in a nest, I expected at first that he would bring companions and perhaps overwhelm my hospitality with mere numbers, but he did nothing of the kind. I have an idea that he was detailed to the fly catching work just as other workers were busy gathering nectar and honey dew for the young and others still were nest and comb building. Later in the summer another did come, but I am convinced that he happened on the other’s game preserve by accident and was not invited. The two between them must have captured thousands of flies and carried them off alive to their nest.

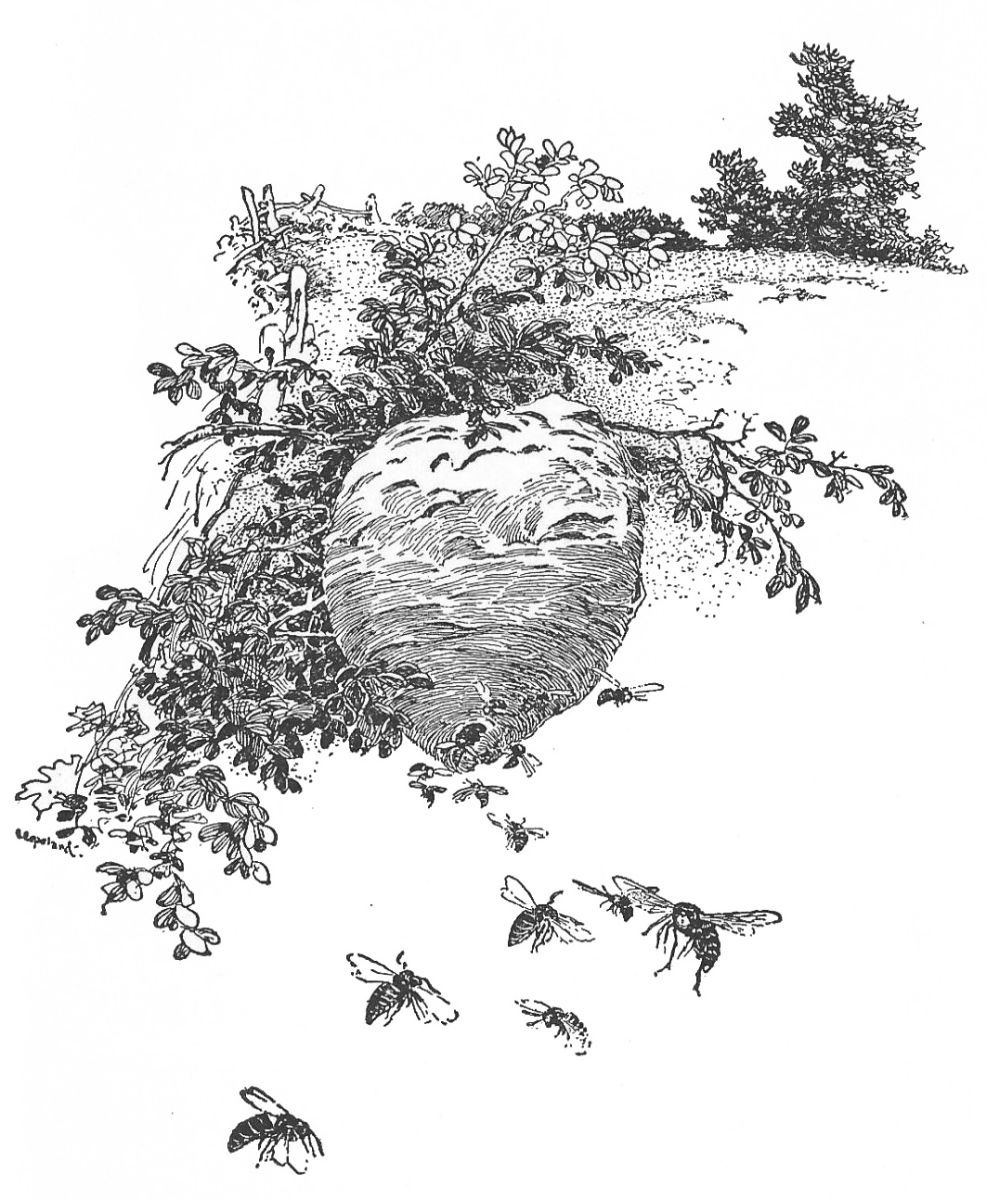

Thus their paper fort, hung from the twigs of a blueberry bush, had by September grown to the dimensions of a water-bucket and contained a prodigious swarm of valiant fighters and mighty laborers, so much will persistent labor, even by near-sighted, dunder-headed hornets, accomplish. I say near-sighted, for the two specimens of Vespa maculata who used to hunt flies in my tent were certainly that. I say also dunder-headed, for if not that they would have learned eventually the location of that tack head and ceased to capture it. Barring these failings, no doubt congenital, I know of no pasture people who show greater virtues or more of them than the white-faced hornets.

Their paper fort had by September grown to the dimensions of a water-bucket and contained a prodigious swarm of valiant fighters

The weak beginnings of their great community home in the berry bush were made in early May when a single lean and hungry queen mother crept from a crevice in the heart of a great hollow chestnut where she had survived the winter. She sunned herself for a time at the opening, then began eagerly chewing fibre from a gray and bare dead limb near by. She chewed this and when it was softened to a pulp she flew straight to the berry bush and began her long summer’s work. Laboring patiently she made and brought enough of the paper pulp moistened with her own saliva to form a nest half the size of an egg containing just a few cells in a single comb that was horizontal and opened downward. In these she laid an egg each, worker’s eggs.

Always the first brood is of workers only, and it would seem that the mother hornet is able by some strange necromancy to lay an egg which shall produce, as she wills, a worker, a drone or another queen, for the hornet hive, like that of the honey-bee, has the three varieties. While these eggs hatch she completes the nest and then begins feeding the funny little white maggots which hang head down in the cells, stuck to the top by a sort of glue which was deposited with the egg.

Honey and pollen is the food which the youngsters receive, varied as they grow up with a meat hash of insects caught by the mother and chewed fine. Soon they fill the cells, stop eating, and spin for themselves a sort of silk night shirt and a cap with which they close the mouth of the cell. Here they remain quiet for a few days, changing from grub to winged creature as does a butterfly during the chrysalis stage of its existence.

Those were busy days for the queen mother, for she had the work and the care of the whole wee hive on her hands, and she showed herself capable not only of doing her own feminine part in the hive economy, but that of half a dozen workers as well, making paper, doing construction work, finding and bringing honey and pollen and insects for the food of the young grubs, and finally helping them cut away the seals to the cells and grasping the young hornets in her mandibles and hauling them out of their comb.

These young hornets washed their faces, cleaned their antennæ, ate one more free meal and set to work. Thereafter the queen mother, having reared her retinue, worked no more, but kept the hive and produced worker eggs as new cells were provided for them, now and then perhaps feeding the children when the workers were busiest.

The first care of the new-born workers was to clean out the once used cells and to build new ones. But there was no room for new comb within the thin paper envelope which the mother had built as a first hive. They therefore cut this away, chewing it to pulp again, and building new cells with a larger covering all about them. Then below the first comb they hung a second by paper columns so that there was space for them to pass between the two, standing on top of one comb while they fed the young hanging head down in the comb above.

They also added cells to the sides of the old comb, making it much wider. The first little round egg-shaped nest was all of one color, a soft gray, but the new additions are apt to be lighter or darker in color, according to the idiosyncrasies of the individual worker. Some indeed have a faint touch of brown when newly added to the structure though these soon fade, yet you may recognize always the dividing line between one hornet’s work and another’s by the difference in shade.

Thus the work went on during the summer, more cells being added to the existing combs, new combs being hung below, and always the surrounding envelope being cut away and replaced to accommodate the internal growth. Late August saw the last additions made. The hive then roared with life. The summer had been a good one and food was plentiful. Under the bounty of fierce summer heat and ample food the workers had developed a new faculty.

I have given them the masculine pronoun in speaking of them, for they certainly seemed to deserve it. Surely only males could be at once so sharp and so blunt, so burly, so strenuous and so devoid of interest in anything but their work. Yet it is a fact that in August some of the workers began to lay eggs, and if the old proverb that “Like produces like” holds good they still deserve the masculine pronoun, for these eggs produced only males.

At the same time the queen began to lay eggs which were destined to produce other queens. How all this could have been known about beforehand it is hard to tell, but such must have been the fact, for the cells in which these eggs were to be laid were made larger than the others as the greater size of males and females requires.

Thus the climax of the work of the great paper hive was reached. The new queens had been safely reared and had reached maturity when the first chill days of autumn came. These days brought rain, and the change from bustling life to silence was most startling. Almost in a day the hive was deserted. It was as if the entire colony had swarmed, and so they had, but not as a hive of bees swarms. They had left the old home never to return, but not as a colony seeking a new land in which to prosper. The first chill of autumn laid the cold hand of death on their busy life. They went away as individuals and stopped, numbed with cold, wherever the chill caught them.

Where they went it is hard to say, but one hornet or a thousand crawling into a crevice to escape the cold is easily lost in the great world of out-of-doors. No worker survives the winter. I think the intensity of their labors during the summer, the continued use of that energy that bubbles within them all summer long, exhausts them and they succumb easily, worked out. With the young queens it is different. Their work is yet to come, and the strong young life within them gives them vitality to endure the winter, though seemingly frozen stiff in their crevices. Yet only a few of these come through in safety. If the queens of one hive all built next year, the pasture would be a far too busy place for mere man to visit.

It is just as well as it is, yet I am glad that each year sees at least one queen white-face pulp-making in the May sun. Pasture life without her uproarious progeny would lack spice. The great gray nest is pathetic in its emptiness, and I am glad to forget it and its bustling throng, remembering only the one busy worker that used to come into the tent and, having caught his fly, hang head downward from ridge-pole or canvas-edge by one hind foot while all his other feet were busy holding his lamb for the shearing.