SOME JANUARY BIRDS

IT seems to be our lot this winter to have April continually smiling up in the face of January. Again and again the north wind has come down upon us and set his adamantine face against all such folly. The turf has become flint; the ice has been eight inches thick on pond and placid stream, and the very next morning, maybe, the soft air has breathed of spring, and bluebirds have twittered deprecatingly as if glad to be here, but altogether ashamed to be found so out of season. As a matter of fact, of course, some bluebirds winter with us, but they don’t warble “cheerily O” in the teeth of the north winds. On those days you must seek them in the cuddly seclusion of dense evergreens, more than likely among close-set cedars where the blue cedar-berries are still sweet and plenty. But we have had many days in this January of 1909 when the bluebirds have had a right to feel called to at least take a hurried glimpse at the bird boxes or the holes in the old apple trees, just as people take a flying trip to the summer cottage on a warm Sunday; they know they can’t stay, but it is delightful to just look it over and plan.

I think the crows, though they are tough old winter residents, have something of the same impulse to plan nests and make eyes and cooing conversation, one to another. To-day I heard, in the pine treetops of a little pasture wood where several pair nest every year, the unmistakable note. In that great song of Solomon which the whole out-door world will chorus in the full tide of spring the crows have the bass part, no doubt, but they sing it none the less musically. It is surprising what a croak can become, between lovers.

I saw them slip away silently and shamefacedly as I approached, and I knew them for callow youngsters, high-school age, let us say, to whom shy love-making is never quite out of season. But they got their come-uppance the moment they sailed out of the grove, for their appearance was greeted with a wild and raucous chorus of crow ha-ha-ha’s. High in the air, flapping round and round in silence above the pines, a half dozen riotous youngsters of their own age had been observing them, chuckling no doubt and winking to one another, and now that the culprits were driven out into the open where all could see them the chorus of jeers knew no bounds. It was as unmistakable as the caressing tone, this jeering laughter. You had but to hear it to know very well what they were saying. The crow language has but one word, which in type is caw. But their inflections and tone qualities are such that it is easy to make it express the whole diatonic scale of primitive emotion.

Many of our summer birds whose winter range barely includes us seem to be more than usually prevalent this winter. It may be that the mild season has to do with this, but it is equally probable that a plenitude of food is more directly responsible. Seed-eating birds are particularly in luck this year. I do not know of a winter when the birch trees have fruited so plentifully, nor have I noticed so many flocks of song sparrows as this year. I find them twittering happily along through the wood, hanging in quite unsparrow-like attitudes from slender birch twigs, busy robbing the pendant cones of their tiny seeds. In the summer you know the song sparrow as a very erect bird. He sits on some topmost twig of cedar or berry bush and pours forth quite the cheeriest and sweetest home song of the pasture land. Or perchance he flies, and the usual short and oft-repeated refrain seems to be broken up by flutter of his wings into a longer, softer, and more varied song that has less of challenge and more of sweet content in it. In his winter notes, which are really nothing but a cheery twittering, I always think I hear something of the mellow singing quality of this song of the wing.

To-day I saw a sharp-shinned hawk, hunting noiselessly, no doubt for these same sparrows. He flitted among the treetops like a nervous flash of slaty gray, and was gone so quickly that had I not heard the welt of his wing tips on the resisting air as he turned a sharp corner I should never have seen him. Most of our hawks, though well known to take an occasional chicken, are mouse and grasshopper eaters. The sharp-shinned is the real chicken hawk, for he eats more birds than anything else, though the small songsters of the thicket form the greater part of his diet. I have rarely seen him here in winter, though his summer nest is common in the deep woods, with its cream-buff eggs heavily blotched with chocolate brown. Just as the plenitude of food of their kind kept the song sparrows with us to enjoy the mild weather, so I think the multitude of song sparrows and other succulent titbits made the sharp-shinned hawk willing to winter where he had summered.

All these birds which are wintering as far north as they dare seem to come out and cheer up in the April-like days, but in those which are distinctly January you may tramp the woods for days and not see one of them. The flicker is a rather common bird with us the winter through. In a warm January rain you will often surprise him wandering about in the thawed fields, looking for iced crickets and half concealed grubs and chrysalids among the stubble. Let the snow come deep and the wind blow out of the north and the flicker vanishes from the landscape. It is as if he had gone into a hole and pulled his thirty-six nicknames in after him, so completely has the flicker disappeared. He is a strong-winged bird and I have always been willing to think that at such times he simply whirled aloft on the northerly gale and never lighted till he was a few hundred miles to the south. He could do it easily enough. He would find bare ground and good feeding in the tidewater country of Virginia when New England is three feet under snow and the zero gales are drifting it deeper and freezing the heart out of the very trees in the wood.

The other day, though, I caught one of them sitting in the hollow of an ancient apple tree. There was an opening of some size facing the south into which the midday sun shone with refreshing warmth. Here, sheltered from the bite of the north wind the flicker had tucked himself away and was enjoying his sunny nook much as pigeons do in just the right angle of the city cornices. But he was better off than the pigeons for there were fat grubs in the decaying wood that formed his shelter and he could use his meal ticket without leaving his lodgings. Our woods are full of such hostelries and they shelter more of the woodland creatures than we know as we tramp carelessly by.

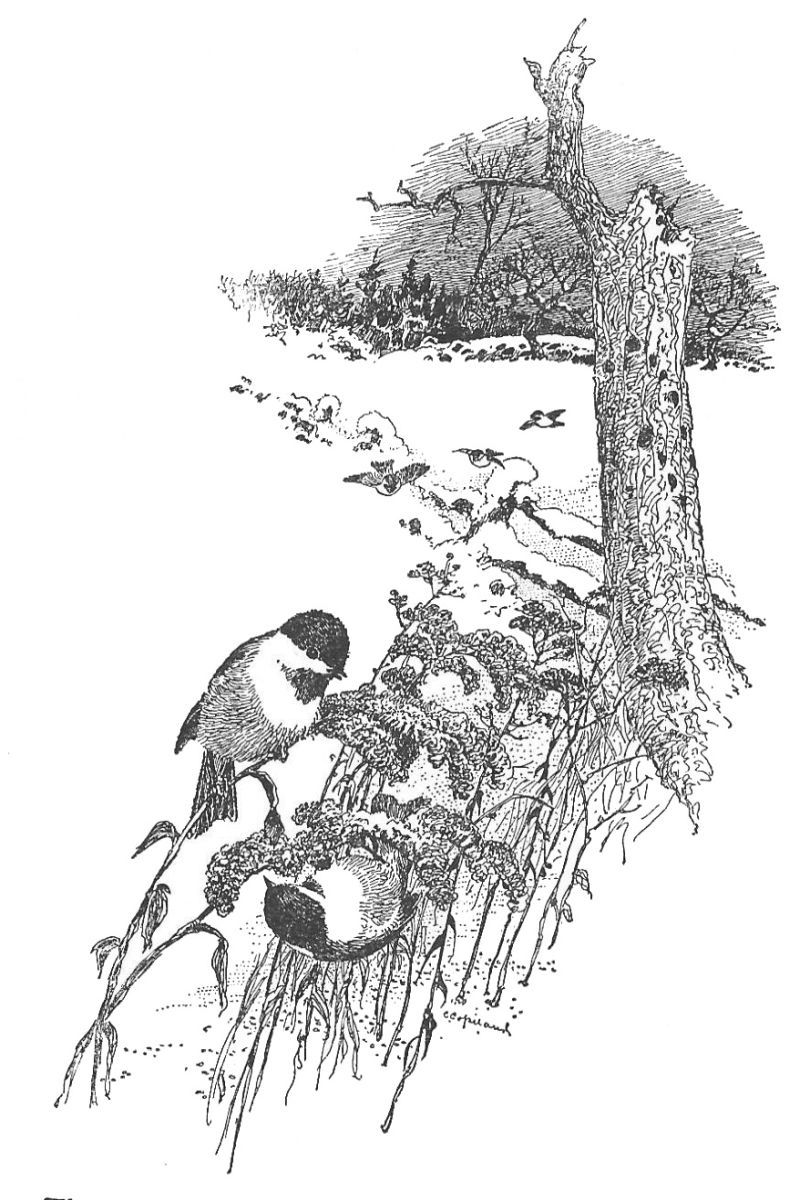

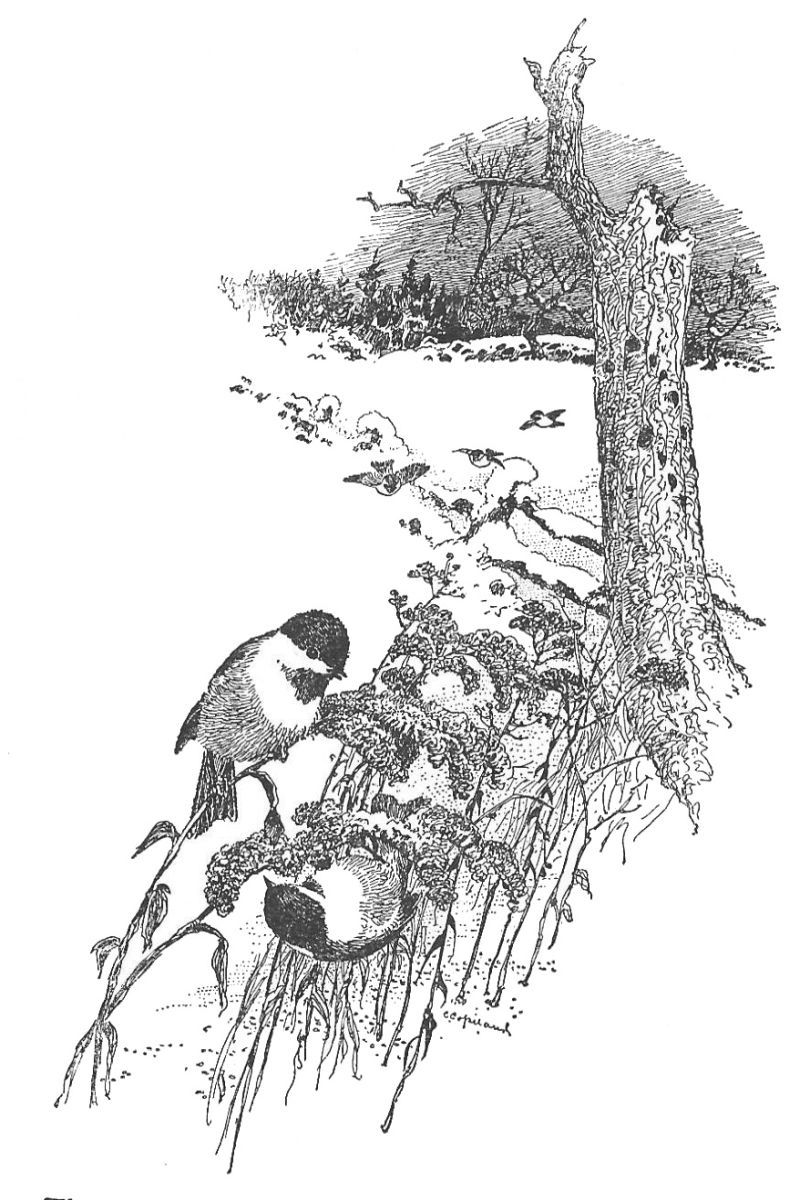

But if the bluebirds and flickers hide themselves securely through the coldest winter days and the song sparrows and even the crows are apt to be scarce and subdued, as is certainly the case in my woods, there are other feathered folk who seem to delight in the cold and be never so gay as when the sky is leaden, the wind bites, and the frost flakes of snow squalls let the sun struggle through the upper atmosphere because it is too bitter cold to really snow. Of these the chickadees lead. They seem to be never so merry as when they hear the sweet music of the tinkle of cold-tense snow crystals on the bare twigs.

In spite of the soft raiment in which the weather garbs itself to-day it is only three days ago that the great organ of the woods piped to the northerly wind as it breathed pedal notes through the pines and piped shrill in the chestnut twigs. And there was more than organ music. The white and red oaks, still holding fast to their brown leaves, gave forth the rattling of a million delicate castanets, and the wind drew like a soft bow across the finer strings of the birches so that all among slender twigs you heard this fine tone of a muted violin singing a little tender song of joy. For the trees were sadly weary of being frozen one day and thawed the next. They thought the real winter was at hand when the cold would be continuous and the snow deep. All we northern-bred folk love the real winter and feel defrauded of our birthright if we do not get it.

There are other feathered folk who seem to delight in the cold

Strangest of all were the beeches. They have held the lower of their tan-pale leaves and with them have whispered of snow all winter long. Whatever the day, you had but to stand among them with closed eyes and you could hear the beech word for snow going tick, tick, tick, all about. It seemed as if flakes must be falling and hitting the leaves so plainly they spoke it. Now that the flakes were beginning the beeches never said a word, but just stood mute and watched it come and listened to the music of all the other trees. Or perhaps they listened to something finer yet. It was only in their enchanted silence that I thought I heard it. Now and then the wind held its breath and the oak leaf castanets ceased, and then for a second I would be sure of it; an elfin tinkle so crepuscular, so gossamer fine that it was less a sound than a thought, the ringing of snow crystal on snow crystal as the feathery flakes touched and separated in the frost-keen air. It surely was there and the beech trees heard it and stood breathless in solemn joy at the sound.

The chickadees were very happy that day. Little groups of half a dozen flipped gaily from tree to tree, bustling awkwardly and jovially about picking up food continually, though it is rarely possible to see what they get as they glean from limb to limb. Winter is the time for sociability, say the chickadees, and they welcome to their number the red-breasted nuthatches that have followed the season down from the Maine woods. The chickadee in his cheery endeavors to take his own in the way of food where he finds it does some surprising acrobatic feats, but they are almost always clumsy and you expect him momentarily to break his neck. Not so the nuthatch. He runs along the under side of a limb with his back to the ground as easily as he would run along the upper side. He comes down the smooth trunk of a pine head down, just as a squirrel does, his feet seeming to be reversible and to stick like clamps wherever he cares to put them. All the time his busy little head is poking here and there with sinuous agility and his slim, pointed bill is gathering in the same invisible food, no doubt, that the chickadee is after. And as he eats he talks, a quaint high-pitched, nasal drawl of yna, yna, yna, that gets on your nerves after a while and you are glad to see him let go his upside-down hold, turn a flip-flap in the air, and light on another tree some distance away. I think Stockton got his idea of negative gravity from watching the nuthatches. If I were mean enough to shoot one I should as soon expect to see him fall up into the sky as down to the earth, so usually regardless and defiant is he toward the proper and accepted force of gravity.

Quite prim and upright as compared with these shifty wrigglers is the third boon companion of these winter day expeditions, the downy woodpecker. You are not so apt to find him as the other two, for his work is deeper and more laborious and they are likely to flit flightily away while he still drills and ogles. Yet you can hear him much farther away than the others, and it is not difficult to slip quietly up and see him at his work. Prim and erect he stands on some rotten stub, his stiff tail-feathers jabbing it to hold him steady, his head now driving his nail-like bill with taps like those of a busy carpenter’s hammer, anon speeding up till it has almost the effect of an electric buzzer. Then he looks solemnly with one eye in at the hole that he has made, prods again eagerly and pulls out a fat white grub, gulps it, and goes hop-toading up the stub looking for more probe possibilities. Or perhaps he writes scrawly Ms. in the atmosphere as he flits jerkily over to the next tree that pleases him.

Thus though not of a feather these three flock together in the biting cold of winter days and seem to be cheery and courageous if not exactly contented. They are all hole-born and hole-building birds and when night overtakes them they know well where to find wind-proof hollow trunks where they may snuggle, round and warm in their fluffed out feathers till dawn calls them to work again.

Yet, with all the yearning of the trees and the joy of the woodland creatures in the prospect of snow it ended in no snow storm. All day long the sun shone palely through a frost fog and the frost crystals sprang out of it at the touch of the icy wind and tinkled into snowflakes right before your eyes. The wind swept a feathery fluff together in corners but at nightfall when the moon shone through a clearer air and a near-zero temperature the crystals had begun to evaporate, and by morning hardly a trace of them was left. To-day it is April-like; to-morrow we may have zero weather again and before these words get into print perhaps the yearned-for snow will have come and with its kindly shelter covered the succulent green things of pasture and woodland that need it so badly.

It is wonderful, though, how they stand freezing and thawing and yet remain green, firm in texture, and wholesome. The birds of the air have feathers which they can fluff out and make into a down puff for a winter night covering. Here in the pine grove is the pipsissewa starring the ground with its rich green clumps. It is as full of color and sap, seemingly, as it was in July when its fragrant wax-like blossoms starred its green with pink. No cell of the fleshy texture of its green leaves is broken nor is there a tarnish in their gloss. Its seedpod stands dry on a dry scape in place of its flower, but that alone shows the difference between summer and winter. Yet it stands naked to the north wind protected by neither feathers nor fur. Who can tell me by what principle it remains so? Why is the thin-leaved pyrola and the partridge berry, puny creeping vine that it is, still green and unharmed by frost when the tough, leathery leaves of the great oak tree not far off are withered and brown?

Chlorophyl, and cellular structure, and fibro-vascular bundles in the one plant wither and lose color and turn brown at a touch of frost. In another not ten feet away they stand the rigors of our northern winters and come out in the spring, seemingly unharmed and fit to carry on the internal economy of the plant’s life until it shall produce new leaves to take their places. Then in the mild air of early summer these winter darers fade and die. Here in the swamp the tough and woody cat-o’-nine-tails is brown and papery to the tip of its six-foot stalk. The blue flag that was a foot high is brown and withered alongside it, yet the tender young leaves of the Ranunculus repens growing between the two and not having a tenth of their strength are tender and young and green and unharmed still. The first two died at a touch of the frost. The buttercup leaves have been frozen and thawed a score of times without hurt.

You might guess that the swamp water has an elixir in it that saves the life of the repens; but how about the Ranunculus bulbosus, European cousin of the repens? That grows on the sandy hillside, and even the root tips that extend below its little white bulb have been frozen stiff a score of times since the woody stemmed goldenrod beside it dropped dead, sere and brown, at the first good freeze. Yet to-day in the smiling sun I found the young leaves of the Ranunculus bulbosus green and succulent and unharmed of their cellular structure, and so I am sure they will remain, under the snow or bare, as the case may be when the first yellow bud pushes upward from that white bulb where it is now patiently waiting the word. Our botanists who study heroically to find some minute variation in form that they may add another Latin name to their text-books might study these variations in habit and result and tell me the reason for them. I’d be glad to buy some more books on botany; but none that I have seen have so far within their pages any explanation of this puzzle.