CHAPTER V

THE CAPITAL OF ENGLAND

This royal throne of kings ...

Fear’d by their breed and famous by their birth.

WITH the dawn of the ninth century came further development. During the 200 years or so of the so-called Heptarchy, a gradual and continuous movement of cohesion—social as well as political—had been in progress. The strength of the Anglo-Saxon was his courage, a determination and persistence hardly distinguishable from obstinacy; his weakness was his lack of imagination and his narrow political horizon. He had never learnt to think nationally, hardly even tribally, far less imperially; his thoughts centred themselves in the little hamlet or home settlement where all were kin at least, if not kind. He took

the rustic murmur of his bourg

For the great wave that echoed round the world.

And if he thought of his fellow-countrymen at all, apart from family blood-feuds which called for vengeance, it was probably in the exclusive spirit of Jacques:

I do desire we may be better strangers.

These individualistic ideas were being slowly modified by existing conditions: families had been grouped into tythings, tythings into hundreds, hundreds into shires; the communal system of land tenure was merging into the manorial system, and with the consolidation of individual kingdoms came a struggle for political supremacy and a movement towards national cohesion and unity. It was the glory of a Wessex king, ruling in Winchester, to render this conception an accomplished fact.

It was at the Court of the great Charlemagne that Egbert gained his political training and insight. Forced as a youth to flee from Wessex, he had been made welcome at the Emperor’s Court, and there in the centre of great world-movements, in a Court which numbered the most accomplished scholars of the time, Egbert began to ‘see things.’ When in 802 A.D. he was called to ascend the throne of Wessex, Charlemagne, it is said, gave him his own sword as a parting gift, but something far more potent—political insight and training—was his already.

Egbert set himself not only to consolidate his power in Wessex, but to weld the separate jangling factions into one under his personal supremacy. The details of this long struggle are part of English history and do not concern us here: suffice it that he asserted the supremacy of Wessex over the whole land, and it is in connection with him that the term England—Angleland—was first used. In 829 A.D. he held a council at Winchester and proclaimed himself King of Angleland.

Winchester thus entered on a new phase, as capital of England and not of Wessex merely, and its importance rapidly developed.

It was well for the land that internal union was thus in sight, for with Egbert’s reign a new danger arose. The migratory racial movements of which the coming to Britain of Jute, Angle, and Saxon was but a phase, had never ceased, but the conditions had altered. In earlier unsettled days new-comers as they crossed the Swan’s Bath had been usually welcomed as allies, now when the land had become settled, when wealth had accumulated in town and monastery, the late-comers came in guise of a foreign foe. Egbert’s reign saw a great revival of the descents of these Danes or Northmen as they were called. Wherever their ‘aescas’ or longships appeared panic seized the countryside. Murder, outrage, conflagration, and ruin were the ordinary incidents of a Viking raid. Men might well pray as they did, “From the fury of the Northmen, good Lord, deliver us,” for the invader knew nothing of mercy, and his enterprise and desperate valour were only equalled by his fiendish delight in cruelty. Egbert struggled long, and, on the whole, successfully, against these foes. In 839 he died, after a reign of thirty-seven years, and his bones are still preserved in a mortuary chest in the Cathedral of his capital.

The words on the chest are:

Hic rex Egbertus pausat

(Here rests King Egbert).

Surely Winchester, which preserves the bones of him who first strove for and successfully realized the conception of national unity, should be the Mecca for all true devotees of Great or Greater Britain.

Like master, like man, and great kings have always had great subjects. Such a one was Swithun, Bishop of Winchester, whose influence was all powerful during the next half century, and was reflected in Egbert’s still greater grandson, Alfred. Swithun belongs essentially to Winchester; he laboured incessantly for the kingdom, the diocese, and the city, and his shrine became for centuries afterwards the glory of its Cathedral, and the place of pilgrimage for thousands of pious feet. He built churches; he protected the Cathedral and Monastery by building a wall round it; he built a bridge across the river, outside the East Gate of the city, where the present graceful Georgian structure stands. As some old verses tell us:

Seynt Swithun his bishopricke to al goodnesse drough,

The towne also of Winchester he amended enough,

For he lette the strong bruge without the towne arere,

And fond thereto lym and ston and the workmen that were there.

Fate deals unkindly with some, even at times with those who deserve most at her hands; Swithun is one of these. A man of saintly life and far-reaching influence, his humility and aversion to display were among his most striking personal characteristics. With an instinctive and indeed prophetic dread of superstitious veneration being paid to his remains after death, he gave orders that his body should be buried, not within the Cathedral, where kings and saints reposed, but in the open graveyard outside, among the poor and the unnoticed. But in vain: with the monastic revival in King Edgar’s reign, one hundred years later, came the erection of a new and more splendid cathedral. Tales of miraculous occurrence began to be told of Swithun’s tomb, and nothing would serve but the translation and enshrinement within the new Cathedral of the saint, so pre-eminently national, whose bones had such potent virtue. Accordingly, in solemn state, in the presence of King Edgar, Archbishop Dunstan, and Bishop Æthelwold, the pious translation was performed. Thus Swithun, never formally canonized, became by universal consent dignified by the appellation Saint, and his mortal remains were for centuries the object of that superstitious worship which he himself had so earnestly dreaded. Later years obscured his reputation even more: a tradition grew up that the saint had signified his displeasure at the translation of his body by sending a violent deluge of rain, which for forty days rendered his exhumation impossible. No foundation for this impossible story can be found in any contemporary account, and several contemporary accounts both minute and circumstantial still exist; but the tradition has passed into a proverb, and so the name of Swithun—his virtues, his piety, and his personality all forgotten—serves often merely to suggest the school-boy jingle:

St. Swithun’s day, if thou dost rain,

For forty days it will remain;

St. Swithun’s day, if thou be’est fair,

For forty days ’twill rain nae mair.

For the general public he has ceased to be a historic personality at all, entitled to veneration and esteem, and has come to be regarded as a mythical being, malignant and capricious, the patron saint of discomfort and of stormy skies.

The century which followed Egbert’s death was one of unremitting struggle against the Danes—a struggle during which the newly formed kingdom seemed more than once in imminent danger of being submerged. Æthelwulf and his sons faced the danger manfully, through which, at length, Alfred emerged victorious. The history of Winchester is in large measure merely the history of these movements.

Æthelwulf, the priest-monarch, the son of Egbert, who succeeded him in 839, will be best remembered in Winchester as the father of Alfred, and by the charters, particularly two of extreme interest, which he executed here. The more important of these is still extant, and the original is preserved in the British Museum. This is often spoken of as the origin of tithes, but erroneously, as Æthelwulf’s gift was a gift to the Church not of produce, but of one-tenth of his landed possessions.

The charter conferring this grant, having been duly executed, was solemnly laid on the high altar of the Cathedral in the presence of Swithun and the assembled Witan. The actual original of the second charter no longer exists, but an ancient copy is preserved among the treasures of the Cathedral Library. Even as a copy it possesses extreme interest: it bears the names of King Adulfus (Æthelwulf), Swithun, and the King’s four sons, Æthelbald, Æthelbert, Æthelred, and Alfred—the two elder sons being described as ‘Dux’ (Earldorman), and each of the two younger, mere boys at the time, as ‘Filius Regis,’ son of the King. Each name is attested, according to Saxon custom, not by a seal, but by a cross. The date is 854, when Alfred was five years old, and the document is the earliest tangible link still existing between the city and the great King.

Of Æthelwulf’s other acts, his two marriages, his journey to Rome, and his grant to the Pope of Peter’s Pence, as a ransom to relieve the sufferings of English pilgrims journeying thither, we cannot speak in detail. Suffice it that Alfred was taken to Rome by him when quite young, and was solemnly confirmed by the Pope himself. Æthelwulf died in 857, and was buried in the Cathedral. His bones rest in a mortuary chest mingled with those of Kynegils.

Each of his four sons succeeded him, one after other, and during their reigns the Danish incursions grew in frequency and intensity: 857 saw them repulsed with heavy slaughter in Southampton Water; in 860 they came again, forced their way to Winchester itself, burnt and sacked it. The Cathedral and Monastery appear to have escaped, thanks possibly to the strong, defending wall which Swithun had erected.

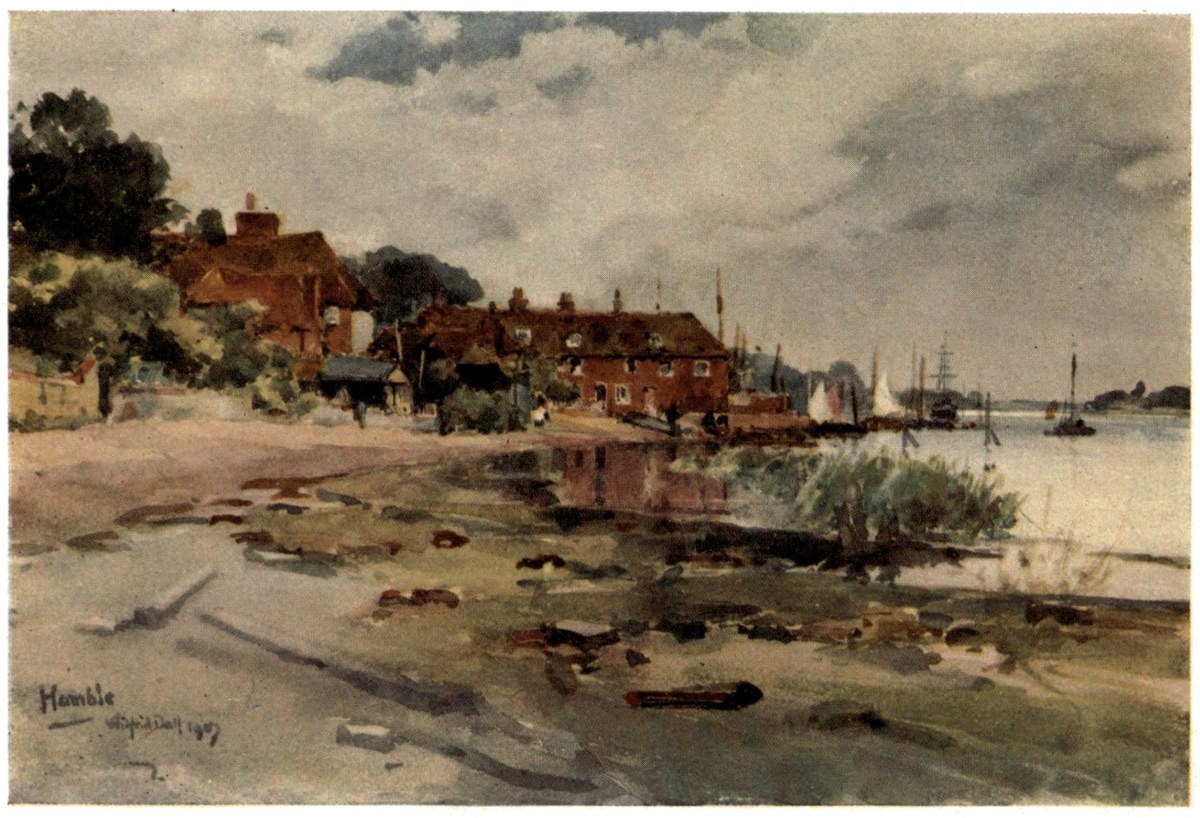

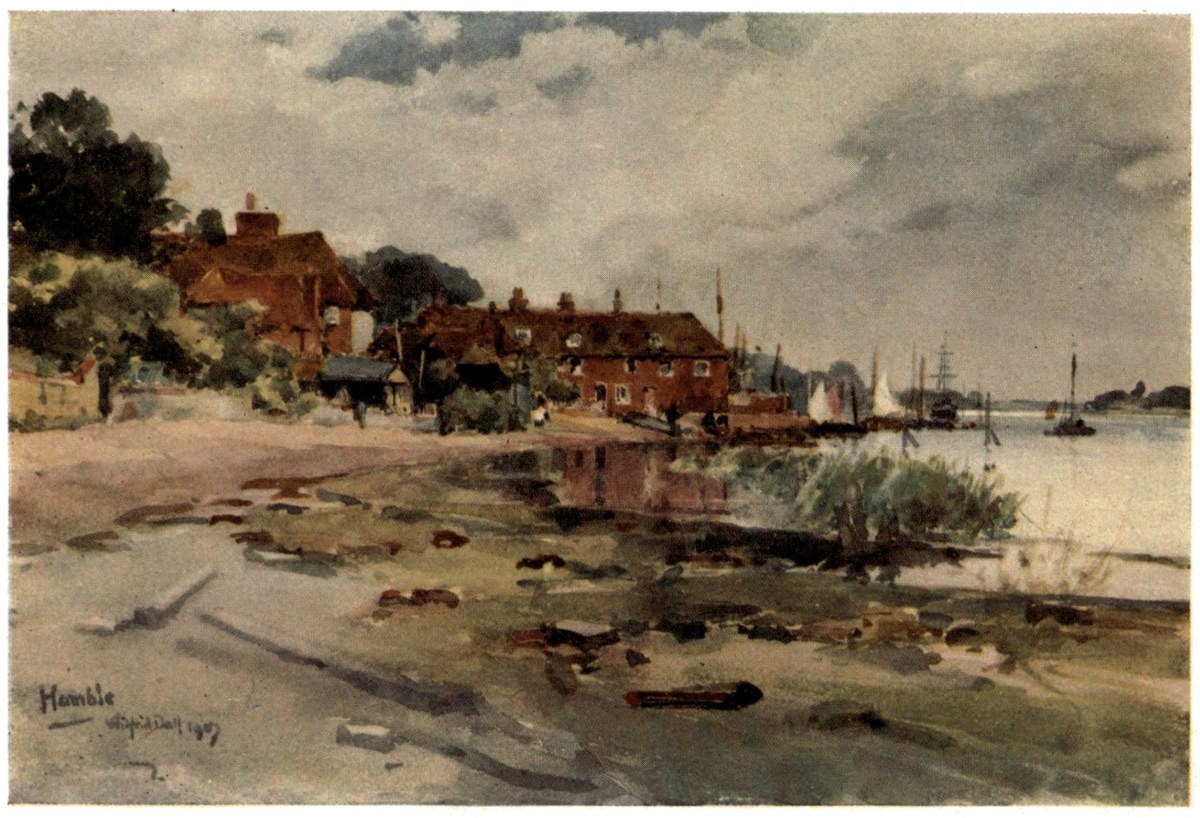

HAMBLE

A characteristic seaport village at the mouth of Hamble estuary—the centre of an important crab and lobster trade. In the mud of the tidal river lies embedded an ancient Danish “longship,” supposed to have figured in the Danish descents of Alfred the Great’s time. The Mercury Training Ship lies moored here; its masts and yards can be seen up the river. The rich red brick and tile work of Hamble village forms in summer-time a delightful picture from the water, with the blue of the river and the yachts in front and the dark trees behind. Warsash lies just opposite Hamble, and Netley just behind it.

Æthelbert succeeded to Æthelbald, Æthelred to Æthelbert, and ever the struggle increased in intensity. In the last year of Æthelred’s reign he and Alfred fought no less than nine pitched battles against the Danes. In the winter of 871 Æthelred died, as it would seem, mortally wounded in battle, and was buried at Wimborne, and Alfred, the last of the four brothers, became king.