CHAPTER XI

LATER NORMAN DAYS

They shot him dead on the Nine-stone Brig

Beside the Headless Cross,

And they left him lying in his blood

Upon the moor and moss.

BARTHRAM’S DIRGE.

WHEN William the Conqueror died, the link with Normandy was temporarily severed, and during the reign of Rufus of evil memory Winchester declined in political importance; nor, apart from one or two episodes, are the Winchester memories of the reign of a striking character. It witnessed, indeed, the practical completion of Walkelyn’s life-work—the great cathedral—as well as the institution of St. Giles’s Fair, as already mentioned, but these belong in essence, though not in time, rather to the epoch of the Conqueror than to that of his violent-minded successor.

Most characteristic of all events of the reign was the long-drawn-out struggle between Rufus and Archbishop Anselm—“the fierce young bull and the old sheep,” as Anselm himself had in dismal prognostication dubbed them. On Lanfranc’s death in 1089 William kept the see vacant for several years, as was his practice in matters of church preferment, in the meantime shamelessly appropriating the temporalities of the see; and when as a result of a dangerous illness he at last agreed to appoint a successor, it was only with extreme reluctance and forebodings of ill that Anselm was at last prevailed on to accept the king’s nomination. Anselm’s fears were fully justified, and a state of hopeless strife soon existed between the two. To all Anselm’s demands, particularly his demand to go to Rome for investiture, the king returned an inflexible refusal, until a crisis was reached at a great council held in Winchester, memorable as the last personal meeting between the king and the archbishop. Every form of pressure was brought to bear on Anselm; he refused, as a matter of conscience, to give way, and finally announced his intention of going to Rome without the king’s sanction, as he could not go with it.

The king raged and stormed in vain, till Anselm, as he turned to leave the royal presence, begged permission to give him his blessing. “I refuse not thy blessing,” said the king, somewhat subdued; he inclined his head, and Anselm signed the sign of the cross over him. They never met again.

The last scene of all in the reign is, however, Winchester’s most dramatic, as well as tragic, recollection. On the afternoon of Lammas Day (August 1), 1100, news came to Winchester that the Red King, who had been hunting that day in the New Forest, had there met a violent death. Prince Henry, his younger brother, with his followers had spurred into the city bringing the tidings, had seized the Royal Treasure, and had summoned the Witan to pronounce him king. Meanwhile the Red King’s body, alone and untended, lay weltering in blood on the spot where he had fallen, till a charcoal-burner, Purkess by name, travelling along had found it and placed it in his cart, that the poor remains might at least have decent sepulture in the cathedral of the diocese. As the news spread in the city an eager throng gathered and watched the road to await the sorry funeral cortège, as it made its mournful way, probably along the road from Compton through the south gate, and so into the old monastery. The interment took place the very next day, right under the tower—“on the Thursday he was slain, and on the morning after buried”; and when a few years later the Norman tower fell upon the tomb, men said it was the Red King’s crimes and not structural weakness that had occasioned the fall. His bones were transferred later on to one of the mortuary chests on the side screens of the choir, but popular tradition still points to a tomb beneath the tower as the tomb where he was originally buried, and speaks of it as Rufus’s Tomb.

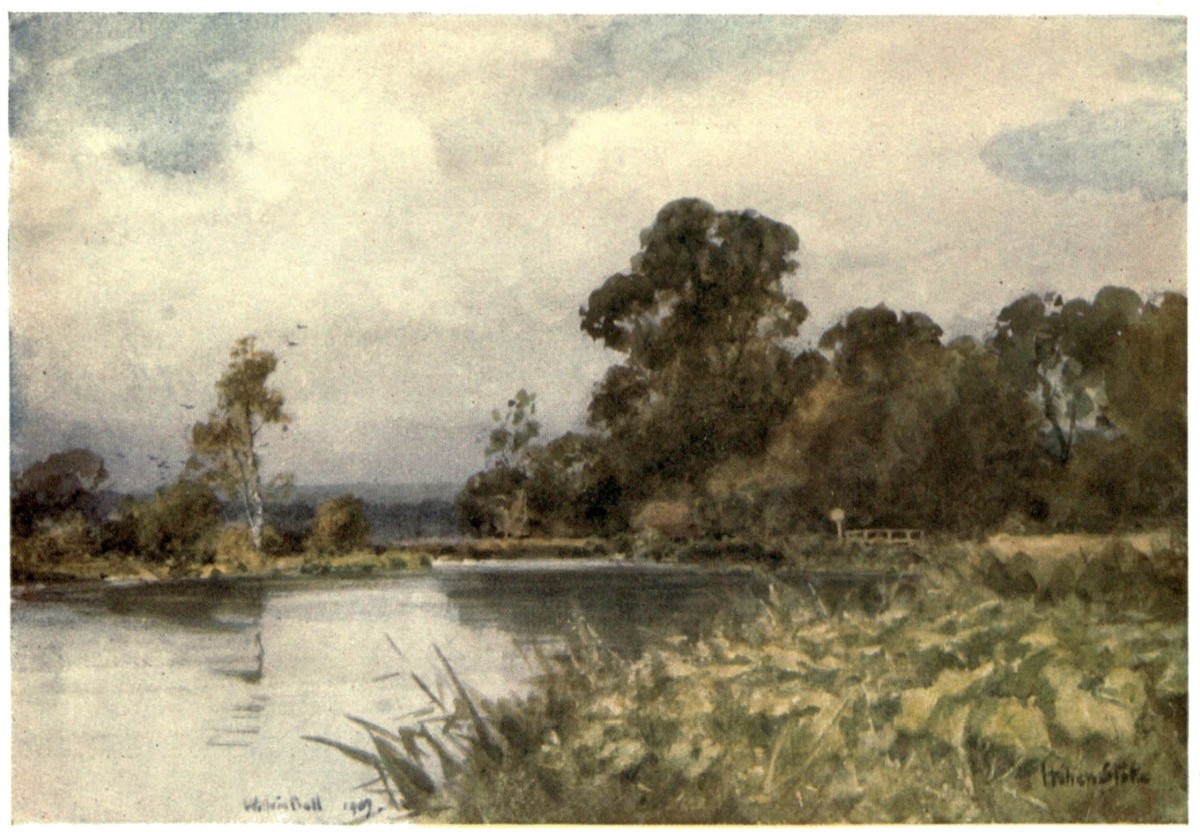

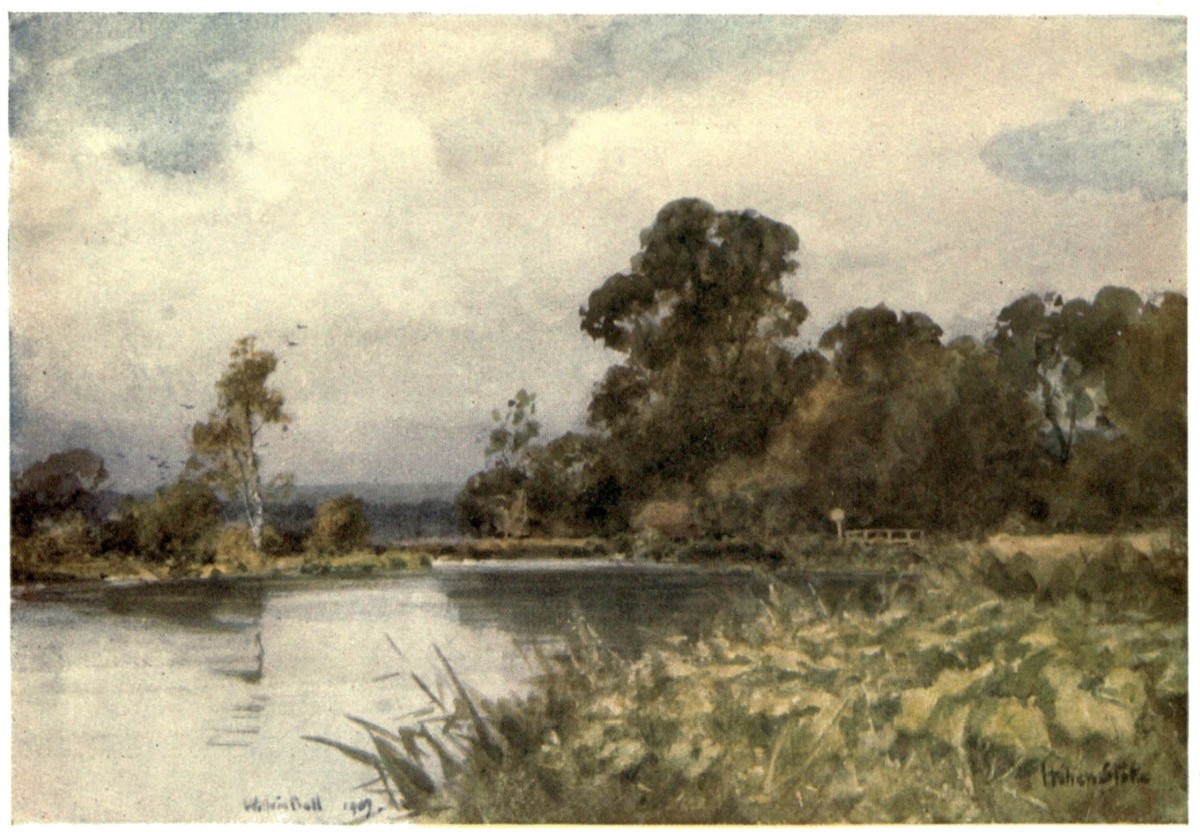

WATERSPLASH AT ITCHEN STOKE

Perhaps the prettiest reach of the river Itchen—and that is saying a good deal—lying between Itchen Stoke and Ovington. The road between them crosses the main stream in a delightful ‘watersplash.’

And now, with Henry on the throne, Winchester resumed its former political importance. Henry reunited the Norman provinces to England, and the old activity of intercourse across the seas was resumed. But more than that, Henry identified himself with the city more closely than any king has ever done before or since. His romantic marriage with the Saxon princess Eadgyth, of Romsey Abbey, grand-daughter of Edmund Ironside, made him popular, and after his marriage he and his queen—the good queen Molde the people called her—made Winchester Castle their residence, and here their son William, the ill-fated hero of the White Ship tragedy, was born.

With its old political position restored, and the king reigning and residing here in person, Winchester rose to the zenith of its importance in Norman days.

A number of events of interest are identified with this reign. First and foremost, the birth of Hyde Abbey. Newan Mynstre, the pious offspring of Alfred and Edward the Elder, had since the translation of Swithun’s bones, during Æthelwold’s régime, steadily declined in importance, and its activity had been much hampered. The proximity to the older and more extensive foundation, which eclipsed and overshadowed it in importance, was one cause; another was the cramped nature of the site upon which the New Minster had been erected.

Always small and confined, so close were their respective churches that chanting in one disturbed the devotions in the other. The erection of William the Conqueror’s palace had made matters still worse, and the monks had had to forego a portion of their already over-congested area. Under these circumstances William Giffard, who had succeeded Walkelyn as Bishop of Winchester, obtained from Henry permission to move the monastery to the village of Hyde in the northern suburbs of the city, and here near Danemark Mead, where Guy of Warwick was said to have vanquished Colbrand the Dane, the new structure was commenced. The immediate result was highly satisfactory.

The monks of St. Swithun’s, who also had suffered from the over-close proximity and congestion, as well as from the rivalry of its over-close neighbour, heartily co-operated and granted the site for the new abbey. Old rivalries were allayed, and for a time a spirit of cordiality prevailed, while as a means of raising funds to assist both houses the king’s grant of a three days’ fair was added to, and an extension given for five additional days, making eight altogether.

In 1110 all was ready, and the monks of Newan Mynstre proceeded in solemn procession to take possession of their new home, bearing with them their sacred relics—the great cross of gold given by Cnut and Emma, and the remains of their illustrious dead, Alfred and Alswitha and their son Edward, for reinterment in the glorious new Abbey Church. Newan Mynstre had so far lasted for some 200 years; now it entered on a new and amplified existence—an existence destined to endure for over 400 years, during which, as Hyde Abbey, it was to maintain a proud and exalted position among the monasteries of the land, till Henry VIII.’s commissioners dissolved and swept it away, leaving what is now a scanty ruin merely—a gateway and little else—to speak of the former glories of the once famous foundation of Alfred the Great.

Of interest and importance only second to that of the erection of Hyde Abbey was the appointment of the bishop, Henry of Blois, who succeeded to the see on the death of William Giffard in 1129—a man of high birth and extreme eminence, who was to play a leading part both in the national fortunes and in the fortunes of the city for over forty years. His career we shall deal with more fully in the next chapter.

As to the condition of Winchester in Henry’s reign we have fortunately sources of exact and unusually ample information. From the Domesday Survey of William the Conqueror, Winchester and London had been entirely omitted. Henry gave orders for a Winchester Domesday, as it is sometimes termed, to be compiled—a survey limited, it is true, to the king’s lands, that is, the lands in Winchester paying land-tax and brug-tax (the latter a tax of uncertain nature, perhaps dues on brewing). This was supplemented by a second survey made some years after by order of Bishop Henry of Blois; and the results of the two surveys are of peculiar importance and interest, for though the church properties are left entirely unnoticed, we glean from it knowledge, not only of the streets and properties, but also of the occupations and handicrafts, et hoc genus omne, of Norman Winchester.

The mode of taking the census was peculiar. Eighty-six of the leading burghers were empanelled and sworn to hold a grand inquest, and to return a faithful verdict. From their labours we gather not only that the Norman city, in its general ground plan, its walls, gates, and the dispositions of its streets, reproduced very closely many of the features of the original city erected by the Romans, but that that general character has remained practically undisturbed to the present day. The main artery and commercial thoroughfare was then, as now, the High Street, referred to only indirectly in the census as Vicus Magnus. Nearly all the other streets crossed it at right angles and were named after the different trades followed in them; and we gather that in Winchester, as in all other mediaeval towns, each trade had its own special street or quarter, and their general disposition was somewhat according to the scheme annexed.

Some few of these names linger still, though practically all the special industries have long since disappeared. Minster Street has survived and for obvious reasons, Sildwortenestret and Bucchestrete have survived to modern times in Silver Hill and Busket Lane respectively, while Gere Street or Gar Street, curiously enough, survives, though all but unrecognisably, in Trafalgar Street. The list of the trades alone is lengthy and varied, and in itself a telling testimony to the prosperity of the city at the time. The occupations of cloth-weaving, tailoring, tanning, remind us of the great industry of the district—sheep-rearing—the wool and other products of which formed the staple attraction for continental merchants to throng to the city

|

Westgate.

|

|

|

|

The Castle.

|

—

|

— Snidelingestret (or Tailors’ Street), now Westgate Lane.

|

|

Gerestret (or Gar Street, now Trafalgar Street).

|

—

|

— Bredenestret (now Staple Gardens). Here later on the Wool Staple was placed.

|

|

Goldestret (or Gold Street, now Southgate Street).

|

—

|

— Scowertenestret (Shoe-waremen’s Street or Cobblers’ Street), now Jewry Street. The Jewish Ghetto was here--hence its present name.

|

|

Calpestret (or St. Thomas’s Street).

|

—

|

— Alwarenestret (All-wares-men’s Street or Drapers’ Street), (now disappeared).

|

|

Menstrestret (now Little Minster Street).

|

—

|

— Flesmangerestret (Flesh-mongers’ Street or Butchers’ Shambles), now St. Peter’s Street.

|

|

The Monastic Quarter.

|

—

|

— Sildwortenestret (or Shieldware-men’s Street), now Upper Brook Street. The name survives in Silver Hill.

|

|

|

|

— Wenegerestret (or Wongar Street), now Middle Brooks.

|

|

|

|

— Tannerestrete (or Tanners’ Street), now Lower Brook Street.

|

|

On this side also was Colobrochestret (or Colebrook Street). Close by was the [1]Hantachenesle, the quarters of one of the ‘Gilds.’

|

|

— Bucchestrete (near Eastgate).

|

|

Eastgate.

|

|

|

during the fairs of St. Giles. The shieldmakers reflect its military importance, and the goldsmiths the rank and material wealth of those for whom it catered.

Naturally enough, many other interesting details are to be gathered incidentally, e.g. the names of the inhabitants, among which many names still familiar as distinctively Winchester names are to be found, and their various ranks and occupations. We read, for instance, of a market near the three minsters, of which the present Market Street is a survival; of ‘estals,’ or stalls, in the High Street, a reference with a curious modern echo, inasmuch as the stalls in the High Street and Broadway have been quite recently the source of much local heart-burning and contention; of ‘escheopes,’ or shops, which had belonged to the Confessor’s queen, Edith; of reeves (prepositi), and of a ‘stret bidel’ (or street beadle). One curious entry relative to Eastgate speaks of certain steps which gave access to the church above the gate (qdā gradˢ ad ascendendā ad ecclam sup portā), showing that King’s Gate was not alone among the city gates in having a little church above it.

Another important feature we gain information on is the position of the Gilds. These trade organisations had now become important and fully organised; they served for the protection of their members, they made regulations for the conduct of the several trades, and their headquarters were used as clubs or places for general meeting and discussion—the latter including almost as a sine qua non ale-drinking, and that not always in moderation. The Survey contains references to three halls or ‘gild’ headquarters—Lachenictahalla (or chenictes’ hall) near Westgate, the Chenichetehalla near Eastgate (on the site of the present St. John’s Rooms), and the Hantachenesle in Colebrook Street. What the very obscure term Hantachenesle, applied to the last named, means is a problem on which so far no satisfactory light has been thrown. Nor is it clear who the ‘cnechts’ or ‘chenictes’ were—whether, as is generally assumed, they were ‘knights,’ i.e. young men of rank, or ‘cnechts,’ i.e. sons of burghers not yet admitted to the ‘Freedom.’ We read that at the Chenichetehalla, the ‘chenictes’ drank their gild (chenictehalla ubi chenictes potabant Gildam suam), and at the Hantachenesle the ‘approved’ or freemen drank theirs (Hantachenesle ... ubi pbi homiēs Went potabant Gildā suā). That this beer-drinking was often inordinate we gather from various contemporary references, such as Anselm’s rebuke of a certain monk who was given to frequenting the gilds and drinking deeply: in multis inordinate se agit et maxime in bibendo ut in gildis cum ebriosis bibat. There is also a reference to a ‘Gihald’ or ‘Gihalla’—possibly a ‘Gild’ Hall,—and the Pipe Rolls of this reign mention a Tailors’ Gild, and a Chepemanesela, or Chapman’s Hall. The whole subject of these gilds, as well as of their halls, is one of great obscurity, and the references in the Winton Surveys, full of interest as they are, serve rather to whet our curiosity than to actually solve any problems they suggest.

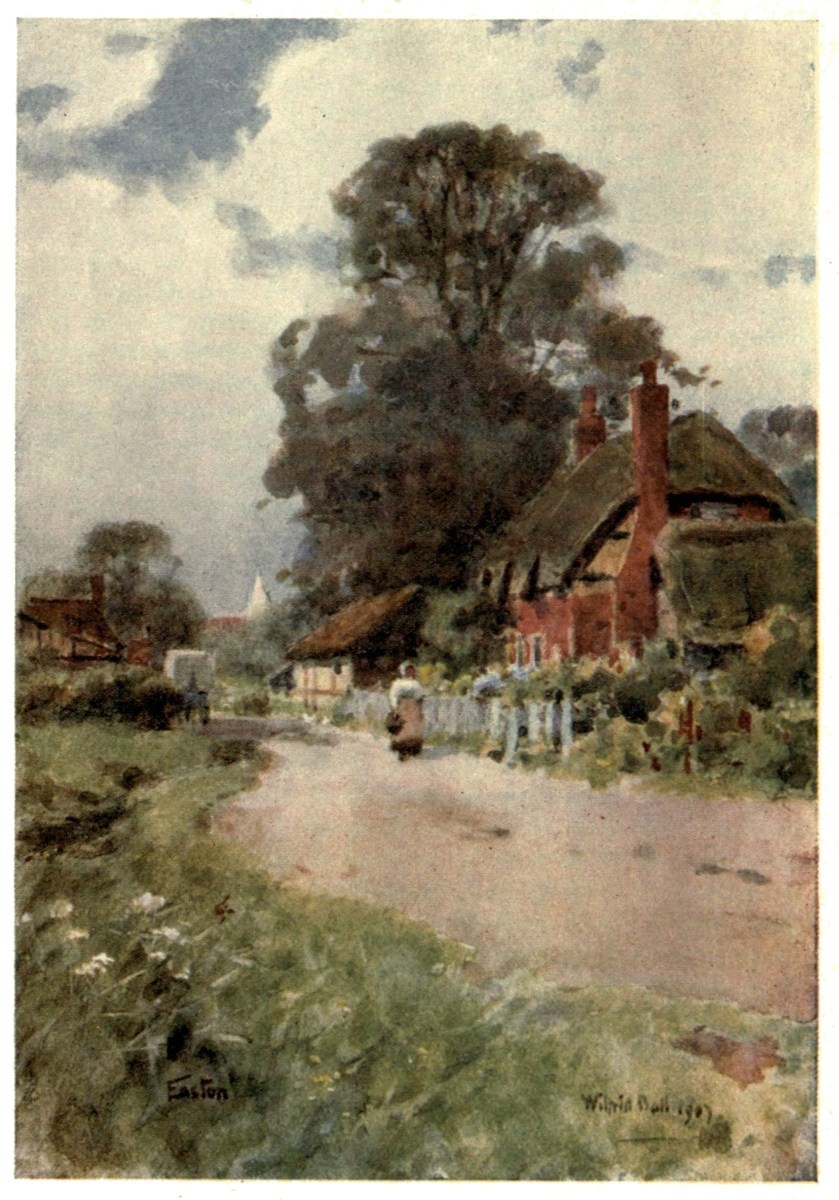

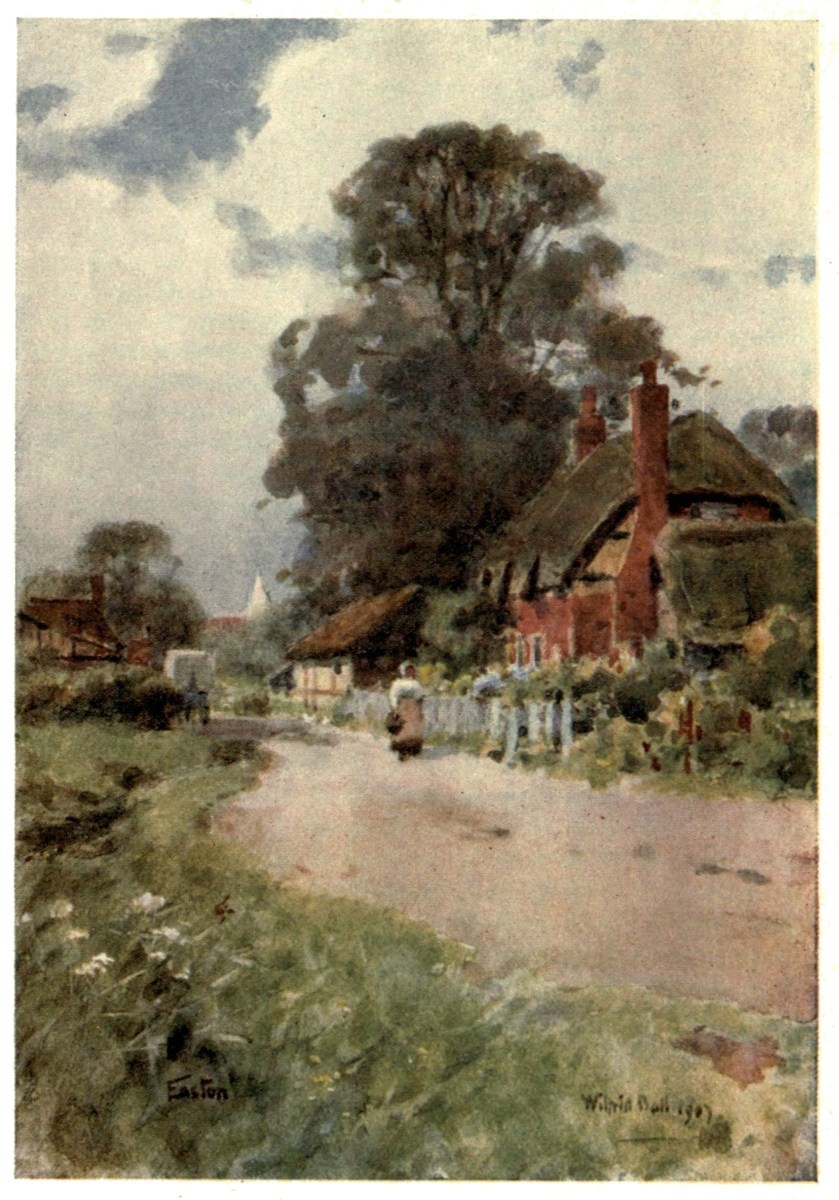

EASTON

A typical Itchen valley village, one of the most picturesque in the county, with an old Norman church, quaint thatched cottages, and clipped yews.

But whatever their exact function and organisation at the time, from them the important Merchant Gild grew, and its hall in High Street (on the site occupied now by the old Guildhall) was the centre for many years of corporate and civic rule, till the erection some forty years ago of the present and more pretentious Guildhall in the Broadway.

The whole circumstances of this so-called Winton Domesday are of unusual interest. The original MSS. exist, bound in an ancient leather binding, considered to be the work of contemporary Winchester craftsmen. These are now the property of the Society of Antiquaries.

Significant among other features of the mediaeval city was the Jewish quarter, or Ghetto, a survival of which we have in the present Jewry Street, at that time Scowertene Street. Abutting on this, in the rear of what are now the extensive premises of the George Hotel, dwelt the Jewish community, with a synagogue of its own, for the Jews were not merely tolerated here, but actually welcomed. The extensive commercial relations now rapidly developing between Winchester and the Continent were doubtless responsible for this, and the Jew in his ancient prescriptive capacity of banker was found to be an effective ally in building up the commercial importance of the rapidly developing city. References to the Jews at Winchester are fairly frequent all through the next two centuries, the period of Winchester’s commercial prosperity. In Richard I.’s reign Richard of Devizes tells us of a Lombard Jew lending money to the Priory of St. Swithun, and lamenting the leniency shown to them by Winchester; while later on in the thirteenth century we read of a Jew—“Benedict, a son of Abraham”—being actually granted the full freedom of the city. These facts reveal to us the scope and the importance held by the Winchester of mediaeval times as an emporium and centre of commerce of more than local repute. But we are anticipating, and we must now return.

The remaining distinctive feature of the city to be noted was the monastic quarter, which occupied practically the whole area between High Street, Calpe Street, and the outer city wall. Foremost in importance was the great Convent of St. Swithun’s—its great cathedral church forming its effective boundary to the north, its great gate opening into Swithun Street close to the little postern gate or King’s Gate, and with the south-eastern edge of the city wall as its southern limit. Behind it, eastward, was the bishop’s residence—Wolvesey, the ancient court of the Saxon kings—and flanking High Street at the eastern end was Nunna Mynstre, or St. Mary’s Abbey, part of the revenues of which were derived from the tolls or octroi duties levied on commodities entering the East Gate.

Such then, in bare outline, was the Winchester of Henry’s reign—not without its miseries, its injustices, it is true, but, as the times went, busy, prosperous, and developing. But this state of things was not to endure for long. Henry’s heir, William, had perished in the White Ship; and though he had done all he could to avert it, the land was to be shortly handed over to a disputed succession and the horrors of civil war when he died. Winchester has good reason to cherish the memory of Henry I. and to recall his reign with satisfaction. He died in 1135, and was buried in Reading Abbey, which he had himself founded.