CHAPTER XIII

ANGEVIN AND PLANTAGENET

Ay, that approves thee, tyrant, what thou art,

No father, king, or shepherd of thy realm;

But one that tears her entrails with thy hands,

And like a thirsty tiger suck’st her blood.

Edward III.

WE need not stay to discuss in much detail the course of events during the reigns which followed. It was but a blackened and ruined Winchester which emerged from the disasters of the civil war. With two monasteries, some twenty churches, and most of the domestic dwellings consumed, it took her all her energies to reconstruct the desolate fabric; nor did she ever completely recover the blow. Hyde Abbey was at once recommenced, and gradually, but only very gradually, resumed its former importance. St. Mary’s Abbey, too, was rebuilt, and Winchester, as the natural centre of the wool trade, was able steadily to recover her commercial activity, and managed to retain her importance as a centre of traffic and intercourse some two hundred years or more longer, but politically her supremacy had departed for ever, and London henceforth was more and more to hold unchallenged sway.

Henry II.’s visits in Winchester were not frequent, and in addition were but casual. It was here, while recovering from illness, that he matured his great scheme for the administration of justice, the division of the country into circuits with itinerating judges of assize, to hold assizes or sittings for the due dispensation of the king’s justice, from which circumstance Hampshire has always occupied a foremost position in the assize list, but Winchester was in no sense his capital.

Richard I. paid the city the compliment of coming here after his release from captivity to be crowned in the Cathedral, and though at the royal banquet following thereon the citizens of Winchester strove with those of London for the honour of serving the king with wine—a privilege involving the reversion of the golden goblet in which the wine was to be served—their claims were overruled and London bore off the prize.

More important were the building projects of the Bishop of Winchester, Bishop Godfrey de Lucy, who had succeeded to the see the year before Richard came to the throne. The pilgrim stream which flowed through Winchester had swollen to such proportions as to embarrass the monks of St. Swithun’s. Bishop Godfrey formed a confraternity to raise funds and carry out an extension eastward of the fabric, to make it possible for the pilgrims to visit the shrine of the saint without invading the body of the church, an extension which, owing to the limited area of firm ground on which the Cathedral stood, had to be made on an artificial foundation, in peaty and waterlogged soil, and to this fact must be in part attributed the insecurity of the fabric, which has necessitated the enormous and heroic labour of repair now actively in progress. Of this, however, more anon.

But Bishop Godfrey de Lucy had wider aims also. As bishop and receiver of the dues from St. Giles’s Fair, the commercial prosperity of the city was of great moment to him, and he improved and developed the Itchen navigation by means of a canal—or “barge river,” as it is termed—and constructed a huge reservoir at Alresford, much of which remains still as Alresford Pond, to retain the water necessary to keep the channel full. The trade of Winchester was evidently still a highly valuable asset.

Of King John’s reign we have memories in keeping with the general course of his doings. He was frequently here, hunting regularly in the forests all round the city, and here his son and successor, Henry of Winchester, afterwards Henry III., was born. It was at Winchester that John received Simon Langton and the other bishops exiled during the interdict, and in the chapter-house of the Cathedral that he received the papal absolution for his offences against Holy Church. But the peace thus dishonourably ushered in was of short duration, and a year or so later Winchester was in foreign hands, being held by Louis, Dauphin of France, whom the barons had invited over to expel John from the throne.

But when John died, as he did shortly afterwards, the barons withdrew their support from the Dauphin, and John’s son Henry, then a lad of nine years old only, ascended the throne—Henry III., Henry of Winchester.

We cannot give in full the story of Henry, interesting and important as it is, and intimately associated as much of it was with our city; for Henry was here continually, he made it his chief residence, and in the years that followed Winchester had often reason to pay dear for his attachment to his parent city. Wild disorder, riot and revel, profuse expenditure and pinch of consequent poverty, anarchy and siege and civil warfare in her streets, all followed in turn, till order was at last evolved, and dignified and noble parliaments assembled in her Castle Hall, the symbol of the reign of law that was to follow, and the earnest of that rule by representative assembly which has made our nation—and almost Winchester herself—the mother of parliaments, honoured through the length and breadth of the world.

Chequered as the reign was to be, the early years were quiet and prosperous, till Henry’s evil genius, Peter de Rupibus, Bishop of Winchester, gained ascendancy over the king. The king’s marriage to a French princess, Eleanor of Provence, followed, and the king, under the influence of a foreign wife, and a prelate and justiciar of alien sympathies, entered on a reckless course of extravagance and anti-national policy which estranged all his subjects’ sympathies. To all posts of honour and preferment, whether civil or ecclesiastical, foreign claimants were preferred, and the land groaned under the tyranny of alien domination, while its resources were being drained away from it to provide revenues for foreign beneficiaries abroad. Protest after protest, discontent, active opposition, ridicule, and remonstrance were all in vain. The king was once significantly asked by the witty Roger Bacon what dangers by sea a skilful pilot would most avoid, and on evading the question was told ‘Petrae et rupes’ (stones and rocks), a faintly-veiled allusion to the chief influence for evil in the state. But all was in vain, and at last armed opposition could no longer be prevented, and the barons under Simon de Montfort broke out into open revolt.

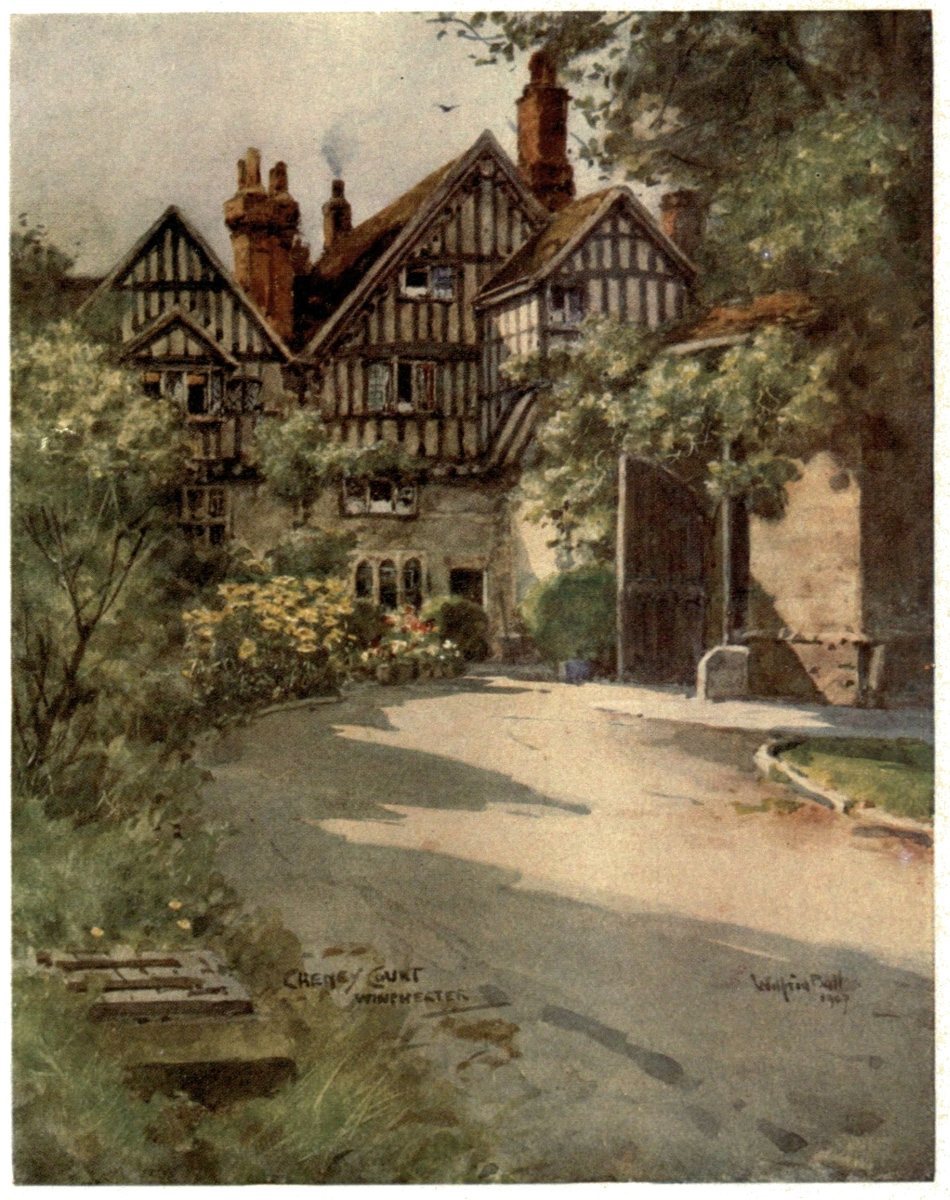

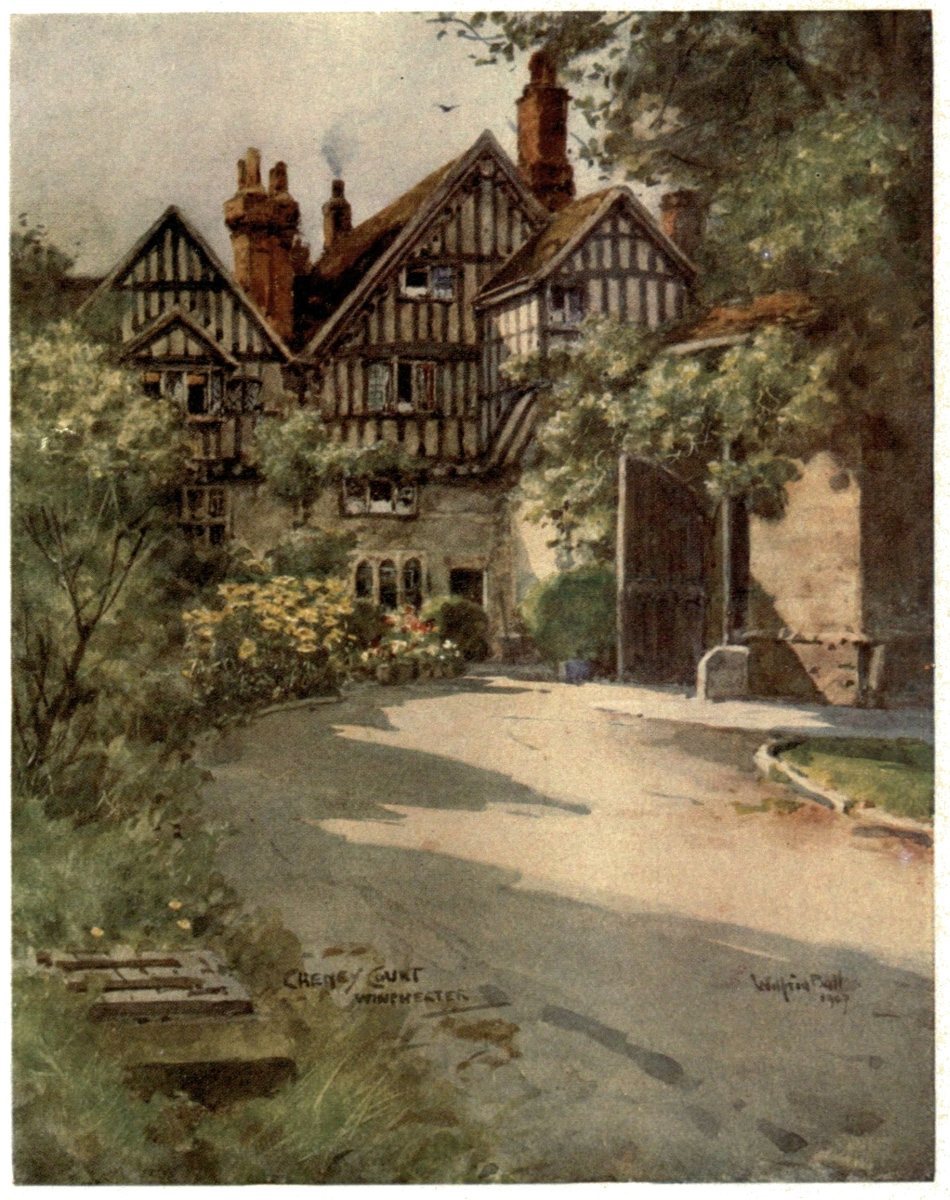

CHEYNEY COURT AND CLOSE GATE, WINCHESTER

The outermost ‘court,’ if such a term may be used, of the Cathedral Close, from which the great Close Gate gives access to Swithun’s Street and King’s Gate. The Close Gate is guarded by a porter, as in mediaeval days, who locks and unlocks it regularly by night and day. Near Cheyney Court stands part of the old ‘Guesten Hall,’ where poor pilgrims to the Shrine of St. Swithun used to be lodged. Weird tales of ghostly visitors haunting the Close are told by persons still living. The name Cheyney appears to be derived from the French chêne, an oak.

In the Barons’ War which followed, Hampshire and Winchester were intimately involved. It has been the fate of Winchester, almost from early Saxon days, to have within more than one rallying point for popular sympathy, and so to suffer peculiarly at all crises of national division; and so it was now.

Few in the land had suffered more acutely from the king’s policy of preferring aliens than the monks of St. Swithun, and when the Barons’ War broke out the monks of the convent sided strongly with De Montfort. The citizens, however, held loyally to the king, and thus it came about that when in May 1264, a few days before the battle of Lewes, De Montfort marched against the city, the citizens rose against the convent, fearing lest the monks, who controlled part of the walls and the King’s Gate, should welcome the invaders and admit them to the city. A violent attack was made on them, the Close Gate was burnt down, and the invading citizens burst their way in and slew several of the monks. The fire spread to the King’s Gate and burnt it down; and when later on the gate was rebuilt, the monks of St. Swithun built above it a little church for the use of the lay servitors of the convent, and so the little church—now the parish church of St. Swithun’s, Winchester—came into existence, perched in mid air above the little postern gate. Nor was this all, for the year after, when Simon de Montfort the younger appeared again in arms before the city walls, the monks actually admitted him, and a wild night followed in Winchester; his troops revenged themselves on the defenceless citizens for their opposition by burning and plundering a portion of the city, and putting many of them to the sword. But the ascendancy of the barons was but brief, for in the same year, 1265, Prince Edward defeated and slew De Montfort at the battle of Evesham, rescued his father, and restored him to the throne.

A memorable year was this both for England and for Winchester, for Henry summoned to Winchester his first representative Parliament, notable because for the first time representatives of the cities and boroughs appeared there with knights of the shires, along with the barons and prelates, and the abbots and priors of the leading monasteries. The Prior of St. Swithun’s and the Abbot of Hyde were both present at that remarkable assembly. In 1268 a second Parliament assembled at Winchester, and four years later the king died, and Edward I. became king.

Henry III.’s reign was indeed a notable one for the city, and one notable addition he made to it remains still as one of its foremost architectural and historical treasures. This is the great and noble hall which he added to the castle, and which retains still, with some alteration, much of its original character. Many a notable scene has this noble hall witnessed, both during Henry’s reign and since, the early Parliaments of 1265 and 1268 pre-eminent among them. One such dramatic scene was the one related in full by Matthew of Paris, as occurring in 1249, when the king unmasked and brought to justice a confederacy of robbers who had conspired to waylay the highways and rob the passers-by. None were safe from them: even the king’s own consignments of wine, coming to Winchester, were stopped and plundered. Matters were in this state of insecurity when the king, coming to Winchester, was approached by some Brabantine merchants, who complained that they had been stopped on the highroad near Winchester and robbed of 200 marks. The king’s anger boiled over, and in hot indignation he ordered the castle gates to be shut, and a jury empanelled then and there to find and disclose the offenders. The twelve citizens thus appointed pleaded inability to throw light on the matter, but the king, not to be thwarted, shouted, “Carry away those artful traitors; bind them, and cast them into the dungeons below, and let me have twelve other men, good and true, who will tell us the truth.”

The second jury, with the fear of death thus before them, promptly displayed quicker powers of perception, and laid before the king the detects of a widespread conspiracy, in which many leading men of the city and neighbourhood, as well as of the king’s household, whose pay was probably long in arrear, were implicated. And so justice was done, and for a while travelling abroad was safer.

Thus, now through good report, now through evil, the fortunes of our city waxed and waned, but, in a sense, her day was over. Mediaeval Winchester more and more grew to assume the character of a purely provincial city; one with importance, indeed, with prestige and dignity, but from which, like the so-called ‘buried cities’ of the Zuyder Zee, the wide shores whereon the tides of major national circumstance ebbed and flowed, continually receded more and more, while her citizens found themselves less and less ‘going down in ships’ to the broad sea of national life, and ‘occupying their business’ in those ‘great waters.’