CHAPTER III

THE ROMAN OCCUPATION

Foursquare to all the winds.

THE part played by physical causes, outlined above, is illustrated by the successive stages in the Roman occupation. The two first invasions by Julius Caesar were little more than desultory raids; the next, under Aulus Plautius and Vespasian in A.D. 43, had important and permanent results. Pevensey (Anderida), Portchester (Portus Magnus), and Southampton (Clausentum) were all occupied in turn; up the Itchen valley the invaders came, and its strategic position made them choose Venta Belgarum as their military base in the south of England.

History is silent as to the actual occupation of Venta, but Bede and others mention the occupation of the Isle of Wight, and the silence of Roman writers on this point merely makes it clear that little resistance was encountered here. Nor does Roman literature give us any account of Venta; the only mention of it is in the Antonine Itineraries, the great road-book of the Roman Empire, dating probably from about 320 A.D.; but its importance in Roman days is to be inferred from the remains the Romans have left behind, as well as from Bede and other indirect evidence.

No Roman structure, except, perhaps, some part of the ancient wall still existing, remains above ground now, but the site of the city, as marked out by the Romans, still remains clearly shown, and the spade and pick-axe are continually bringing to light evidences of what Winchester was like in Roman days.

The Roman city formed a rectangle aligned almost exactly with the four points of the compass. Intersecting it from north to south was the great highway leading to Clausentum, and another road, practically corresponding to the present High Street, crossed this at right angles, dividing the whole area of the city into four rectangular blocks or tesserae. All round this area was a wall of stout masonry, with gates at the four points where the two main highways pierced it; upon the same lines were reared later the walls of the Norman city, and their general direction is clearly traceable now. A walk along Westgate Lane, North walls, Eastgate Street, the Weirs (where portions of the ancient wall may still be seen), College Street, Canon Street, and St. James’s Lane, would practically carry us round the circuit of the Roman as it would of the later mediaeval city.

The temples of the gods occupied the south-eastern area where the Cathedral now stands, and a well in the Cathedral crypt is pointed out to visitors as having been connected with heathen worship in Roman times. Numerous pieces of tesselated pavement, vases, urns, and votive objects generally, articles of adornment, for household use and the toilet, are frequently found even still, mingled with innumerable coins and relics of a military nature.

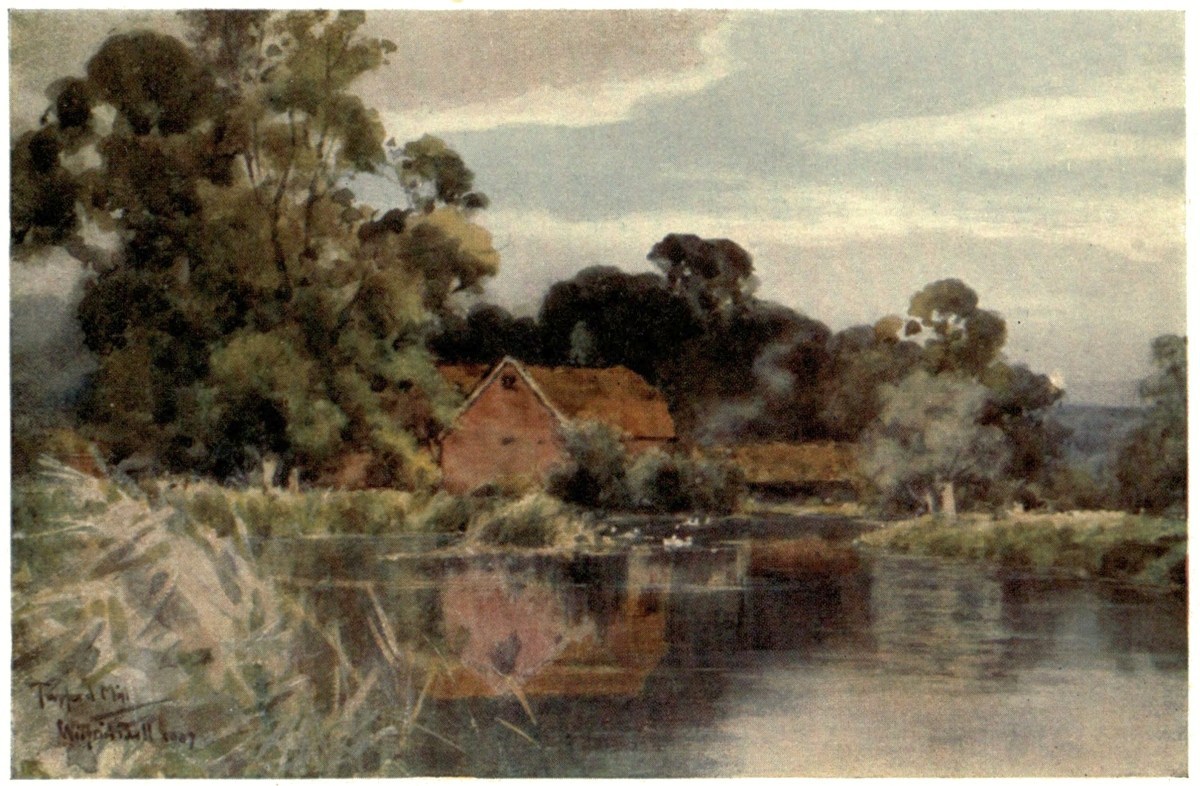

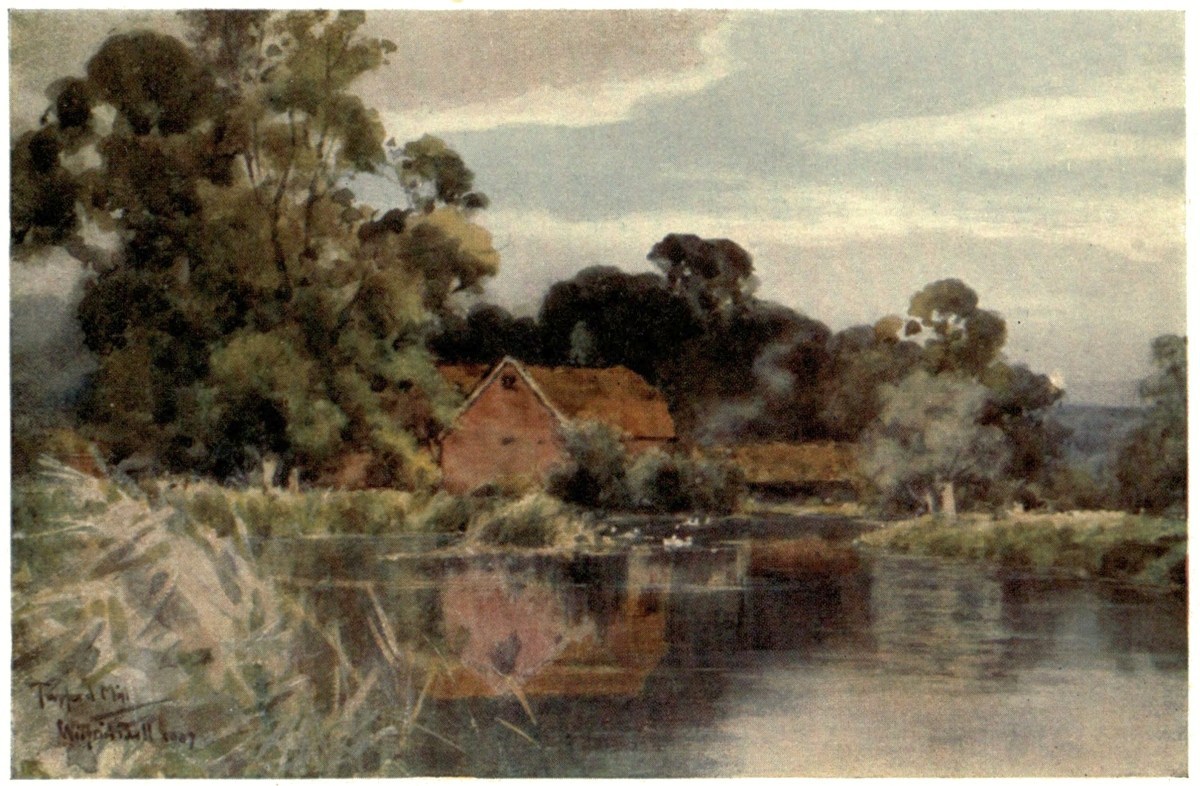

SHAWFORD MILL

Shawford Mill, near Shawford. The river channels here are fringed in summer-time with mimulus, yellow iris, and forget-me-not, and are delightful to ramble along.

More important still are the Roman roads which led from Winchester, the routes of which are still unmistakable, and which remain the great enduring monument both of the Roman occupation and of the Roman civilizing instinct. Indeed, the chief service the Roman occupation did for Winchester was to bring it into effective contact with the rest of the country. The Belgic tribesmen had no common organization or polity; a number of scattered and incoherent units linked together merely by the accident of position, and a more or less common racial descent, they resembled one of the lower animal forms, not possessing a common nerve centre, but controlled by local ganglia and responding merely to local stimuli. The Roman genius was to link up the whole land into one united organism and to supply a nervous and arterial system regulated by central control. Law and Order were the great lessons it taught the world, and open and secure lines of communication were the necessary preliminary of the Pax Romana. No succeeding age save our own has so fully recognized the value of good and effective road communication. Our modern roads and tracks very often merely follow routes first marked out by Roman hands, and the common occurrence of the title ‘High Street,’ generally applied to the leading thoroughfare of town or village, is a constant reminder to us of the debt we owe to the Romans.

Radiating from Venta Belgarum were no less than five thoroughfares, of which four were undoubtedly important arteries. The first led to the sea, to Clausentum, the port. It followed the line of the existing Southampton road as far as Otterbourne, and then straight on through Stoneham (the ad Lapidem of Bede) to Clausentum. This road passed straight through the city from south to north, and from the northern gate of the city it branched off into two, one going north-east, along the existing Basingstoke road to Silchester (Calleva Attrebatum), the other north-west, following the line of the existing Andover road to Cirencester (Durocornovium). Both these roads can be still traced for a distance of a good many miles from Winchester. The fourth led directly west to Sarum, and can still be followed as a well-defined track all the way. The fifth led to Portchester (Portus Magnus) over Deacon Hill, and through Morestead, but with the exception of the first few miles all trace of it is now lost.

Details of some of these roads as given in the Antonine Itinerary already mentioned are quoted below, and the names of the stations and their distances apart are of more than usual interest, particularly from the assistance they give us as regards identification of the Roman sites.

|

Londinium (London) to Pontes (Staines), mille passuum (miles)

|

xxii

|

|

Pontes to Calleva Attrebatum (Silchester)

|

xxii

|

|

Calleva to Venta Belgarum

|

xxii

|

|

Venta to Clausentum (Southampton)

|

x

|

|

Clausentum to Portus Magnus (Portchester)

|

x

|

The Roman routes are not comfortable to follow now, particularly to the cyclist; their course is invariably straight, leading direct from point to point, over hill and valley alike, without regard to gradient or the lie of the land. The appeal they make to the thoughtful imagination is distinct and striking. Direct and uncompromising, they follow their course regardless of obstacles, suggesting irresistibly the genius and energy of the imperious people who met difficulties only to subdue them. Primarily imperial in character, if not always military, few things conduced so much to the settlement and growth in civilization of the land. Commerce followed in the wake of security, and the arts of war ministered thus as handmaid to those of peace.