FAIRY FRUIT

TO-DAY the September west winds have begun the fall house-cleaning by sweeping the tops of the pine woods. All the morning the little brown scales which nestle close to the base of each pine leaf as it grows, protecting it from the withering force of the midsummer sun, have been soaring and spinning in high glee, curiously lighting up with brown glimmers the solemn sanctuaries beneath.

It is the first prophecy of winter under the sheltering boughs where still lingers the midsummer warmth. The chickadees, going their forenoon rounds, scold about it in a brisk fashion that is in tune with the briskness of the wind itself. In the languor of the south wind the chickadee has a little lazy song which he sings often, “Sleepee, sleepee,” a tuneful little ditty that makes you want to stretch out on the brown carpet with a mound of green moss for a pillow and let the resinous odors lull you to sleep. I always feel that the bird himself murmurs it with one eye closed and himself in danger of falling off the perch in slumber.

None of that song to-day. It’s “chick-chickachick, chick-a-chicadee dee dee,” with a snap in it like the crack of a whip. Yet the flock soon passes on, and in the dreamy warmth of the grove you know little of the vivid touch in the wind. Only enough of it comes through to set the little brown pine motes to whirling merrily as they fall, vanishing from sight like flitting elves as they touch the brown carpet below.

There was another elf-like transformation, an appearing and a disappearing, in the woods this morning. That was a Pyrameis atalanta that kept vanishing into the trunk of a big pitch pine. This, the red admiral, own cousin to the familiar Pyrameis carduii, the painted lady, is a butterfly whose movements are as snappy as those of the west wind on these house-cleaning days. Rich red, white and black are the colors on the upper side of its wings, but when these are closed there is exposed only the under side, which makes the creature so exactly like a rough chip of the pitch-pine bark that when he lights on the trunk the vanishing is complete. Out of nothing he sprang, a vivid flash of darting red and white flipping before your eyes, then he darted up to the pine trunk that seemed to open and let him go in, so completely did he transform his bright colors into a bit of brown bark.

The more I see of woodland glades and sun-dappled depths and the creatures that inhabit them the less I am inclined to smile at the elder races of the world that peopled them with fairies, sprites, and goblins. Why should they not believe in these things? It is hard sometimes for us to forego all lingering remnants of faith in such inhabitants of field and wood.

This morning on my way to the grove I seemed to meet with more than the usual number of woodchucks, though you would hardly call it meeting, for our paths never crossed. But in three different parts of the big mowing-field a woodchuck bobbed out of nowhere in particular. No doubt he was feeding on the clover of the farmer’s aftermath, but I saw no more of that than the cropped herbage after the woodchuck was gone. My first sight each time was when the animal began to roll in a straight line across the field. I say roll, for woodchucks at this time of year are so fat that they do not seem to run, but undulate over the grass as does the deep sea wave over the shallows.

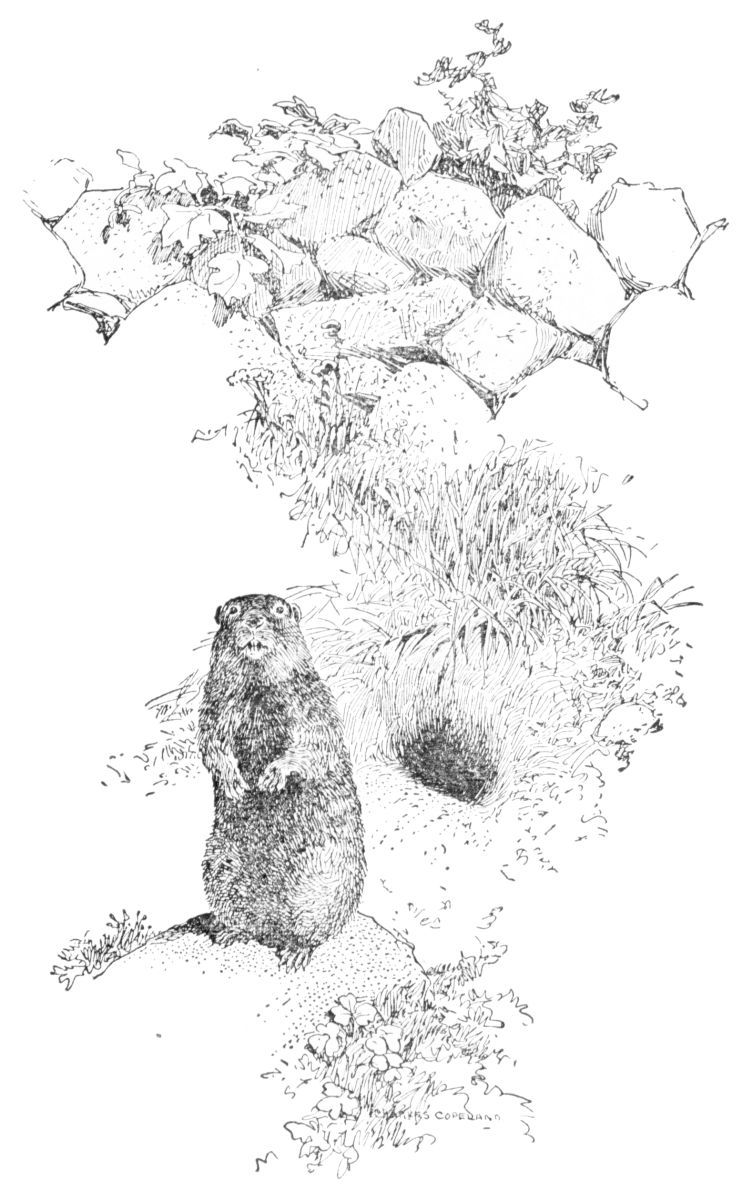

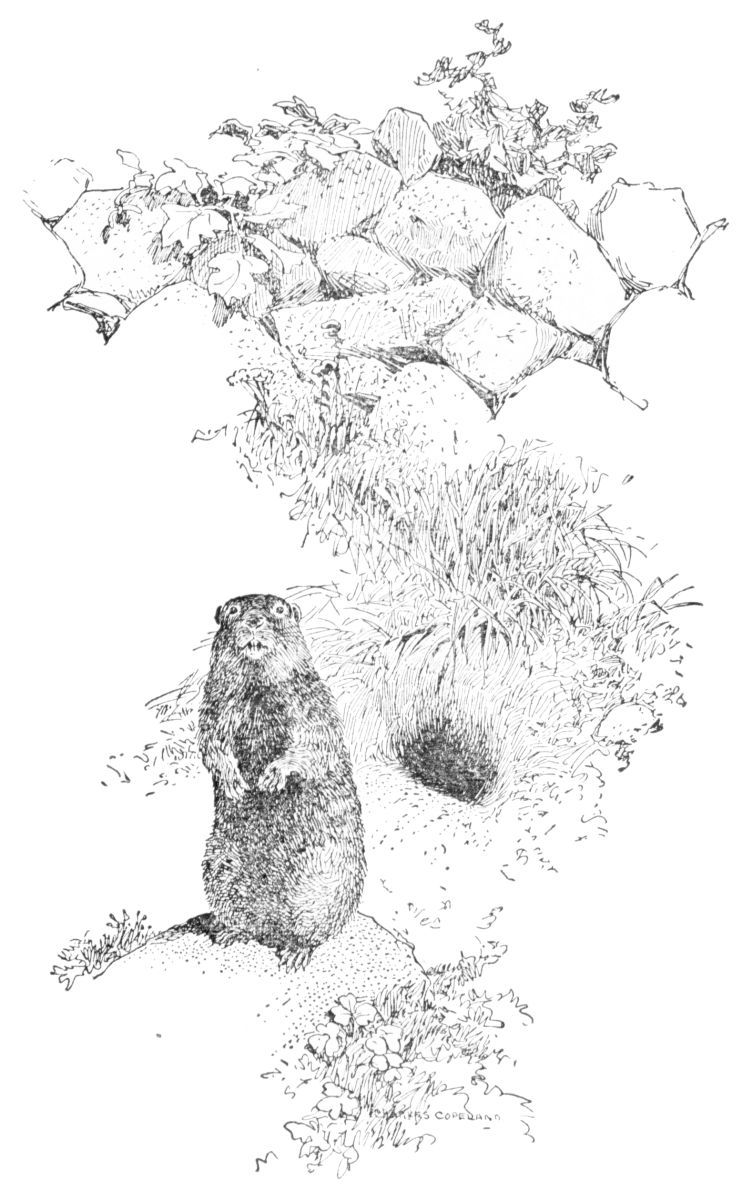

I never can help chasing them, though I know well what is about to happen. Nor do I expect to catch one, for, fat as they are, they move with surprising rapidity. Even if I happen to know where his hole is by the pile of dirt at the door and rush between him and it, I am no nearer getting my game. I always fancy that the fat shoulders of the woodchuck jiggle with laughter and his little pig eyes twinkle, for that is just what he expects and is prepared for. He keeps right on in his straight line, then psst! he vanishes. You don’t see him dive or turn or hide. He just goes out of sight. You may poke about in the grass for a long time before you find the secret entrance by which he has returned to his burrow. Sometimes he has two of them. They are dug from within outward and no tell-tale trace of dirt is left to mark their location. This has all been carried down with infinite pains, then up, and left at the public door, where all may see it. The woodchuck is the very mark and origin of the paunchy gnome, which is said to guard buried treasures, and which bobs out of the earth, frightens Hob from his intended mining, then bobs back into the earth to guard the gold.

So you have but to go into the pine grove to-day with inquiring eye and acquiescent mind and all the beautiful old superstitions that always plead to be taken into the belief will come trooping along, to your supreme delectation. Well might the great and good Wordsworth say, he who knew the open wold and the bosky dell as few of us are privileged to know them, and wrote about them as none of us can:

The woodchuck is the very mark and origin of the paunchy gnome

“Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn,

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea,

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathed horn.”

Here in the pine grove is the riding-school of sylphs innumerable,—those fragile fairies who float in slender grace on the passing breeze. Their launching stands are the flat-topped receptacles of the blooms of Erechthites hieracifolium, the coarse and homely fireweed. All summer it has stood in the open spaces of the wood with its tall stalks bearing blossoms that look like green druggists’ pestles, with no beauty of petal or sepal to entice, no fragrance to call the wandering bee. Indeed, these surly blooms seem like buds that were too cross to open. Now it is different. The green bonds of guardian bracts are reflexed, and you may now see that this unattractive flower has held close pressed within its homely heart companies of sylphs.

White and slender and soft, they stand until the right wind comes along, then they spring fearlessly to his invisible shoulders and are borne whither they list. Not mortal things are these thistledown fairies that are so transparent white that you may look through them as they float by and see the sun. If it pleases them to touch your hand or your cheek as they pass, you may note an ethereality of sensation which is thought rather than feeling, so light it is.

The Epilobium angustifolium, sometimes called willow herb, is another fireweed, as beautiful of bloom as Erechthites is homely. Like this, it grows in waste places in the wood, flaunting its long raceme of showy, pink-purple flowers all summer. Like the Erechthites, too, when September has tamed its exuberance, it is more beautiful still as the abode of white sylphs which cling in whorls to its stem. Yet, mark you the difference. The sylphs, reared by the dour and homely fireweed, stand erect and prim in close communion as stately and correct and dignified as sylphs may be. Those born of the flaunting Epilobium cling to it in graceful, almost voluptuous abandon, assuming such poses as nymphs might in wooing a satyr. Equally beautiful, the first are like prim New England schoolmarms diaphanously gowned for a Greek play; the second suggest artists’ models frolicking in the woodland before being called to pose.

Along with these two fireweeds, breeders of sylphs, in my pine wood grows the pokeweed, a villainous name for a wonderfully vigorous and beautiful plant. Just now its close-set racemes of purple-black berries are ripening, their color a vivid contrast with the smooth rich green of its ovate-oblong leaves and the wine color of its stems. It is really a royal plant, and so great is its vigor that its dark berries threaten to burst their skins and scatter their rich crimson lifeblood. If you will look closely at the berries you will see that the fairies have stitched them neatly across the top to prevent this. The marks of the needle show, and the tiny puckering made by drawing the thread very tight.

It is so workmanlike a performance that I suspect the leprachauns, who are shoemakers, of having been called in to do it,—called in, for the leprachauns, without doubt, have all they can do conveniently, making and mending the fairy shoon. No doubt the brownies, who are domestic fairies and who would be keeping watch of the woodland fruits anent the preserving season, had them attend to this, lest the preserving be a failure. The poke berries look so rich and luscious that I have tried them; but I cannot say that I like the flavor, which is rich indeed, but peculiar. But then, I remember my first olive. They don’t taste half so bad as that did, and compared with pickled limes, which school-girls eat with avidity, they are nectar and ambrosia in one package.

All the under-pine world is spread just now with beautiful berries, for which neither we nor the birds seem to have a taste. There are the partridge berries, which, by the way, I have never seen a partridge eat, nor have I found them in the crops of partridges, which I have been mean enough to shoot. Yet these are, to my mind, the most edible of all, though they are insipidly sweet, and their flavor is so finely pleasant that it is not for the coarse palate of most mortals. Their vines carpet the wood in places, and the soft, pure red of the berries would catch the eye of bird or beast from afar. These stay ripe and sound all winter, and you may see their red shining softly among the evergreen leaves when the bare ground responds, dull and sleepy still, to the resurrection trump of spring. They have not been gobbled whole, therefore the larger animals and birds of the wood do not care for them; but in the spring you will often find them with a tiny bite taken out of one side. This can have been done by no other than the fairy urchins, too young to eat fruit with safety, and forbidden by their mothers, they yet slip out and take a bite before they can be hindered.

Equally beautiful and conspicuous, and equally insipid to the human taste, are the great blue berries of the Clintonia borealis, which grows sparingly under the pines hereabouts. These are as large as the end of your finger, and a wonderful clear shade of prussian blue. If you know the leaf of the lady’s slipper,—the moccasin-flowered orchid which is so common in June under all pines,—you might, thinking of the leaf only, call this the fruit of the lady’s slipper, where, as sometimes happens, but one berry grows on a stem. Yet if you look further you will not long labor under the mistake, for you will find many stalks with several berries, whereas the single blossom of the Cypripedium acaule could leave behind it but one. The fruit of the lady’s slipper is at this time of the year a dry brown pod, whence all the little dry seeds have long ago dropped; indeed, it is only occasionally that you will find the pod left so long.

I do not know but birds eat the beautiful fruit of the Clintonia, though I have never seen them do it, and I fancy it is too insipid to creatures that love wild blackberries, raspberries, and cherries. Yet, as in the case of the partridge berries, I have often seen the fruit with a tiny mouthful taken out of it as it stands on the stalk. This is a bigger mouthful than the marks left in the partridge berries, so I know that it is not fairy urchins which have done it, even if I thought they could climb these tall, slippery stalks. I have a fancy that Queen Mab herself, who, as you very well know, is the fairy midwife as well as queen, flitting home in the dusk of morning from motherly service, has stopped for a brief refreshment on the Clintonia stalk. I even have a notion that I can see in the bitten berries the prints of the wee pearls that are her teeth.

Every little starry bloom of the Smilacina bifolia, which vies with the Mitchella in carpeting the pine wood, leaves behind it a lovely tiny berry that is like a pinhead currant. These, now, are in little groups at the top of the withering stalks. Fairy currants I have heard them called, and I think the name a good one, for they are red and juicy like currants and taste not unlike them, though, like all these fruits, the flavoring is more insipid. They are a lovelier berry before ripening than after, for when young they are a slender sage green, through which the red shows more and more in dappling spots as they ripen, making them a most beautiful warm gray.

I am quite sure that the fairies make jam of these, stowing it away in wild-cherry stone jars, built for them by the stone-mason wood mice, who are very busy with the wild-cherry stones about this time. They drill a little round hole in each and extract the kernel, then put the stones away in their storehouses for sale to the fairies. I have often found these storehouses with the stones put away in them, but have never been fortunate enough to find the fairy larder with the jam in the jars.

I often wonder what the fairies think of the fruit of the nodding trillium, which you will find in the wood now with the others. I fancy they look upon it with wonder and amazement as a miracle of agriculture, just as we, about this time, wonder at the vast pumpkin exhibited at the county fair. It is sometimes almost an inch in diameter, roundish, with six angles or flutings on it, and a very vivid crimson in color.

To the fairies they must seem to grow, like cocoanuts, on palm trees, for the trillium’s erect stem, bearing its spreading palm-like leaves only at the top, is a foot or so high. I imagine they gather these as they fall with great glee, and stow them away for winter use in making fairy pumpkin pies. Often in autumn, along woodland paths in the night, I have seen a faint glow where I was about to set my foot. Always I step aside carefully, for I have been told that this soft, greenish light comes from glowworms.

Yet it is more than likely that sometimes the fairy urchins have been allowed to make jack-o’-lanterns from the smaller of these trillium pumpkins, and this faint glow is the fairy candle within these. After stepping aside you should bend your head and listen. If you hear faint, tinkling laughter, inexpressibly sweet and fine, it is the urchins out with their jack-o’-lanterns, and laughing in glee that they have succeeded in scaring someone.