PROMISE OF MAY

THE first touch of the rose-gray morning air brought to my senses suspicion of two new delights; one, the more sensuously pleasing, to be sought, the other to be hoped for. It was easy to hope for things of such a morning, for there come gracious days in the very passing of April that presage all the seventh heaven of early June.

At such times the pasture people bestir themselves, and no longer march sedately toward the full life of summer, but begin to riot and caper forward. The old Greek myth of fauns dancing on new greensward is not less than fact; by May-day the shrubs caracole. I suspect even the cassandra of wiggling its toes under the morose morass; and though it may not outwardly prance, it puts on the white of new buds as if it at least were coming out of mourning.

By sunrise the riot of the robin symphony had become a fugue, and there was some chance to hear the other birds. I had hoped for a soloist who should certainly be here. The coming of the earlier bird migrants from the South is sometimes delayed by storms or forwarded by pleasant weather, but those which come now are almost sure to appear at a definite date. There are always Baltimore orioles in the elms about my house on the morning of the eighth day of May. No one has yet seen one on the seventh, though the neighborhood takes an interest in the matter and keeps careful watch. It is a matter of twenty-five years since the observations began, and not yet has the date failed. If on that morning I do not see the flash of an oriole’s orange, yellow, and black among the young apple tree leaves, and hear that musical whistle, I shall think something has gone dreadfully wrong with return tickets from Nicaragua.

Of the brown thrush I am not quite so sure. He rarely calls on me. Instead, I have to seek him out on the first few days of his arrival. He likes the sprout land best, and the flash of rufous brown that you get from him as he flits away among the scrub oaks might well be the color of a fox’s brush, yet there is no mistaking his sunrise solo. It is quite the most sonorously musical bird song of early spring, and I have heard it often on the twenty-fifth of April.

I dare say it has always been here as early as that, though some years I have failed of the concert-room and so of the singer. Always he is here by May-day. This morning his rich contralto rang from a birch tip in the pasture where he or some thrush just like him has sung each May-day morning for I do not know how many years. I listened in vain for the chewink, though he too is due. Like the brown thrush he is a thicket-haunting bird, following soon on the trail of the fox sparrow, cultivating the underbrush by claw as he does.

There is no rest for the weary brown leaves of last year, though they may take passage on the March winds to the inmost recesses of the green-brier tangle of the pasture corners. Through March and early April the fox sparrow harries them, and they have hardly settled with a sigh to a brief nap in his trail before the brown thrush and the chewink are at them with bill and toe-nail, and these are here for the summer. About a week later, generally on the very sixth of May, easy going mister catbird will appear with great pretence of bustle. He is a thicket bird, too, but unlike the chewink and the brown thrush his farming is all folderol. He simply potters round on their trail, gleaning. Whatever the thicket-bird name is for Ruth, that is his.

There are sweeter singers in the spring woodland than the brown thrush, but I know of none whose rich voice carries so far, and this one’s rang in my ears through all my wanderings till the sun was high and the dew was well dried off the bushes. Now and then I must needs forget him and even my quest in my joy over the fresh beauties that the shrubs were putting on, seemingly every moment. It is something to look at an olive-brown pasture cedar which has been as demure as a nun all winter and spring, and see it suddenly in bloom from head to foot, as if before your very eyes, coming out all sunclad in cloth of gold. It is no illusion of the sun’s rays or the scintillation of the morning dew, but a rich glow of gold out of the sturdy heart of the plant itself.

Last October I had thought nothing could make a cedar more beautiful than that rich embroidery of blue beading on cloth of olive, which these Indian children of the pasture world donned for winter wear. Now I know their May robes to be lovelier. No doubt they are days in coming out, these tiny blooms of the pasture cedars, yet they always reach the point where I notice them in a flash. One moment they are somber and sedate, the next they are all dipped in sunshine and dimple with a loveliness which is the dearer because it is so unexpected.

You might think it just the foliage of the plant taking on a livelier tint with the coming of glad weather, and there is a change there, but that is only from brown to green. In the severe cold of the winter the leaves seem to suffer a decomposition in the chlorophyl which gives them their green tint and put on a winter garb of brownish hue, but with the coming of the warm days the chlorophyl is reformed, and the brown is rapidly giving place to green when this new transformation flashes on the scene. Right out of the little green leaf-scales grow thousands of tiny golden-brown spikes with a dozen golden mushroom caps ranged in whorls of four about them.

They are not more than an eighth of an inch long, these pollen bearing spikes which will presently loose upon the wind tiny balloons bearing pollen grains to float down the field to the even more rudimentary pistillate flower, but they are big enough to change the gloom of rocky hillsides to a glow of delight, seemingly in an hour. You have but to look about you if you will visit the pasture cedars on May-day, and you may see the place light up with the change.

There is no fragrance to these blooms other than the resinous delight which the leaves themselves distil at the caress of warm suns. It was no odor of the pasture cedars which had given an object to my walk.

The larch is not a native of Massachusetts, but it will grow here fairly well if you plant it, and there are long rows of these trees by the roadside on the way to the pasture. These are all coming forth in the fragile beauty of new ideas. The larch is the mugwump among conifers, dallying irresolutely between two parties. Born a dyed-in-the-wool Republican it has yet of late years leanings toward Democracy. So it votes with the conifers on cones and the deciduous trees on leaves.

Sometimes I cut a larch limb to see if this year one isn’t turning endogenous, and am never sure but the fruit for the new season will turn out to be acorns instead of cones. You never can be sure in what way these independents will surprise you. It is lucky the trees do not have the Australian ballot on what their year’s output shall be. If they did there would be no possibility of predicting what would be the larch crop.

As might be expected, larches are not virile trees, but have a slender beauty which is quite effeminate. Just now their this year’s leaves are a third grown, and are very lovely in their feathery softness, but lovelier yet are the young larch cones, growing along the branches, sessile among the young green of the leaves, translucent, deep rose-pink cameos of cones, that remind you of an etherealized tiny pineapple, a strawberry, and a stiff blossom carved in coral, all in one.

After all, I am convinced that the larches may do as they please about their leaves, vote with the deciduous trees if they wish to, and flout their coniferous ancestry if they will, provided they continue to grow yearly on May first these most delectable of cones. No blossom of the year can show greater beauty.

Baffled in my search for the origin of the sensuous odor which had lured me and which seemed still to drift hither and thither on the variable air, I got the canoe and paddled over alongshore to a cove that I know, a new-moon shaped hiding place behind a barrier reef of rough rocks, further screened by brittle willows that struggle forward year after year, waist deep in water, bravely endeavoring to be trees. They almost succeed, too, in that their trunks tower a modest twenty feet and some of their limbs remain on throughout the year. So brittle are the slender twigs, however, that the least touch seems to take them from the parent tree; and as I push my canoe between them in a favorable channel of the reef I collect an armful in it in brushing by. It is a wonder that the March gales have left any.

Past the barrier and afloat on the slender, placid crescent I found a new-moon world with a life of its own. Rough waves may roll outside, but only the gentlest undulations crinkle the reflections on the mirror surface within. The winds may blow, but rarely a flaw strikes in far enough to ruffle the water. Here, with the sun on my back, I might sit quietly, and soon the normal life of the place, if at first disturbed by my entrance, would go on.

Yet here is no drowsy silence, such as will fill the cove with sleep in August. Passing April may leave things quiet, but they are awake. The first sound which disturbed this quiet was a kerplunk at my side, followed by the grating of a turtle shell over rough rock and a second plunge. Two spotted turtles that had been sunning themselves on a rock at my very elbow as I glided in thus became submarines, and slipped silently away to Ooze Harbor between two sheltering rocks at bottom. These two had been contemplating nature with the sun on their backs, as I planned to, and had been loth to leave such pleasant employment. I think the turtle’s brain may work quickly, but his motions are as slow as those of the Federal Government.

Round about me were the mangrove-like buttonball bushes, showing no signs of green, and the brown heads of hardhack and meadow-sweet blooms of last year bent over their own reflections in the water. Here were gray and brown sackcloth and ashes. Did not the little cove know that Lent was long past? Yes, for here, too, were the maples scattering their red blooms all along the surface; and as I looked again I saw the sage green of young willow leaves just pushing out along the yellow bark of those brittle shoots.

Under the brown heads of the Spiræa formentosa and salicifolia were vivid leaves putting forth, and just as the pasture cedars seemed to jump into bloom before my eyes, so the little crescent cove seemed to garb itself in green as I looked. Under water, too, were all kinds of succulent young herbs just coming up, like the water-parsnip, whose root leaves start in the pond bottom, but which, with the receding waters of summer, will grow rank in the mud of the margin.

A leopard frog sounded his call from the roots of last year’s reeds,—a gentle drawl which has been compared to the sound produced by tearing stout cotton cloth, and perhaps that is as near as one can come to characterizing it, though the sound is a far more mellow and soothing rattle than that. The hylas have ceased their peeping and the wood frogs no longer croak. They have laid their eggs in the warming waters and gone up into the woods. Hitched to a twig a foot beneath the surface I found a jelly-like mass as big as my two fists, which contained a thousand or so of the eggs of the green frog,—Rana clamitans,—and no doubt those of the hylas and wood frogs were to be found nearby. The new-moon cove is a famous frog rendezvous, and a month from now the night there will be clamorous with the cries of many species. You would never believe there were so many varieties till you begin to hunt them by ear.

A pair of robins came and inspected their last year’s nest in a willow over the water, and I saw there a left-over kingbird’s, still holding the space, though the kingbirds themselves will not be back to claim it before the fifth or sixth of May. A silent black and white creeper slipped up and down and all in and about the shoreward bushes, gleaning stealthily and persistently, always with a watchful eye out for possible danger. This watchfulness did not cease when the bird finished hunting and settled down for a noonday nap. It chose for this a spot on the black and white angle of a red alder shrub, where it would look exactly like a knot on the wood. Then it fluffed down into a fat ball of feathers and for a half-hour seemed to snooze, motionless except for its head, that every few seconds turned and looked this way and then that. It was a noonday nap, but it was sleeping with both eyes open.

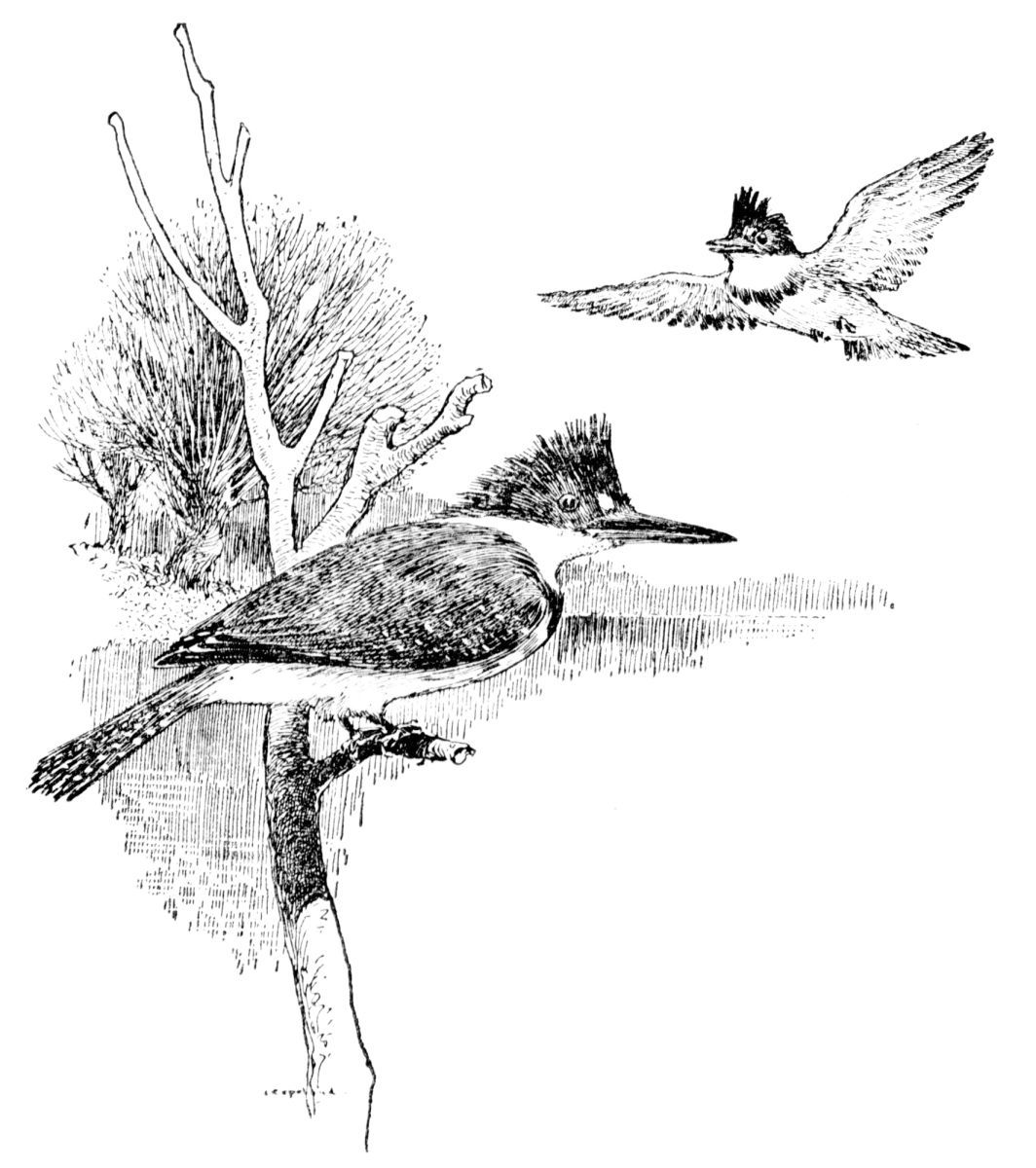

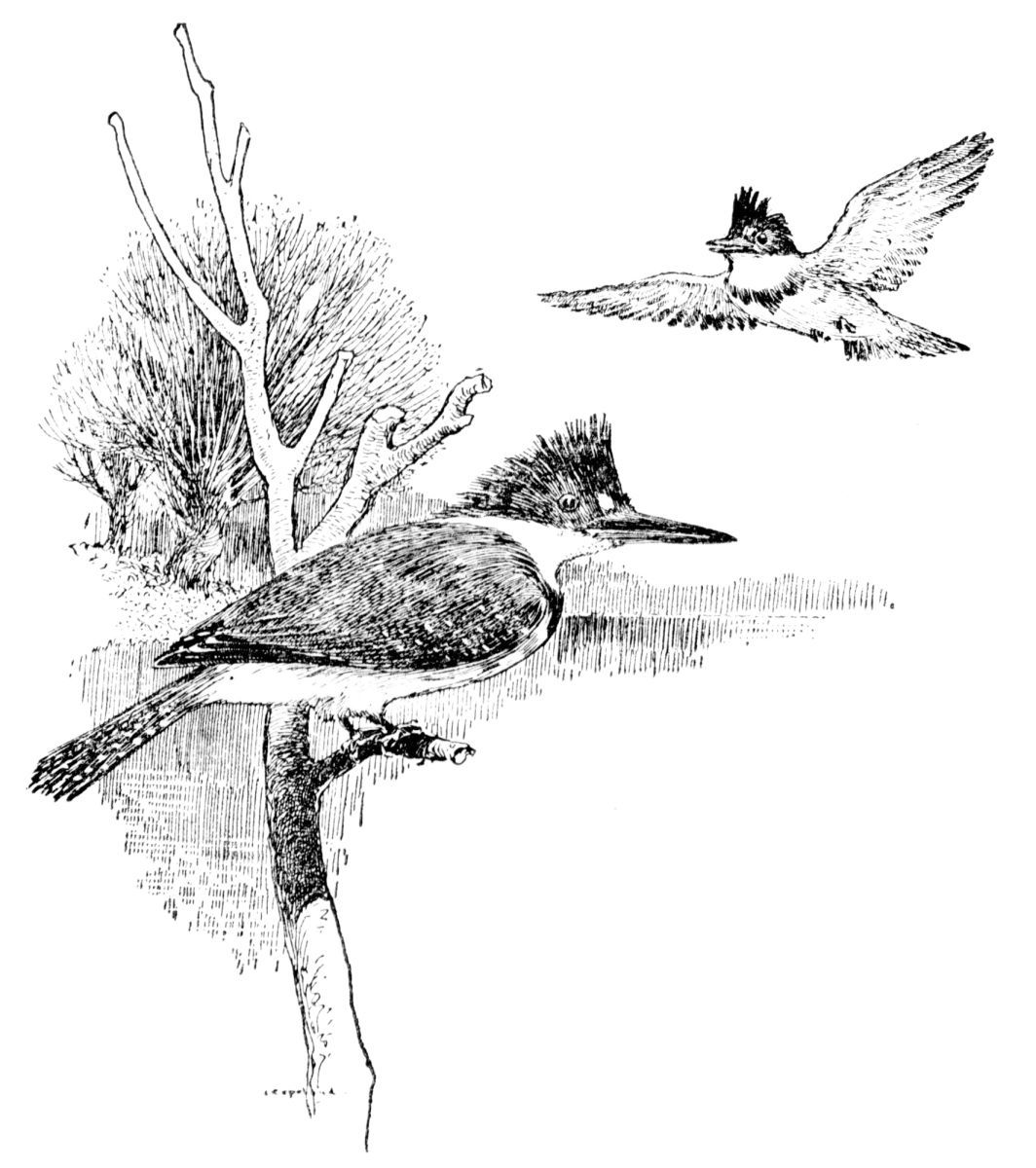

The kingfisher, always an example of nervous energy, flitted back and forth outside the willow barrier, springing his rattle in short vigorous calls. Once he fell into the water with a splash, and came out again with a young white perch in his mouth. By and by he gave an extra shout and went off over the hill and was gone an hour. Then two came back and the air was vivid with friendly staccato calls. But there seemed to be a disagreement later, for after a little the first bird was alone again. Then he began to fly back and forth, high over the cove, till his white throat seemed a sister to the young moon, paper white in the zenith.

The air was vivid with friendly staccato calls

All the kingfisher calls before that had been brief, but now as he flew he clattered like an alarm clock,—the kind that begins at ghostly hours and continues without intermission till you finally get up in despair and throw it out the window. His cry would begin with his leaving the point beyond the cove on one side, continue without a break as he swung high, and only cease when he had dropped to earth again on the other side. Where he got the wind for this continuous vaudeville I cannot say. I have never heard a kingfisher call so long without an interval before, but I take it to have been a far cry sent out for that vanished mate. Perhaps she answered finally, for he betook himself off after a little, I hope to a rendezvous.

While I listened in the silence for the returning call of the kingfisher, a little shore wind came over my shoulder and brought to me the same delicious, sensuous perfume that I had noticed in the early morning, only where it had then been as slender as a hope it was now rich and full with the joy of fulfilment. I looked back in some wonder at the rocky marsh behind the cove, but now I saw farther than the alders and maples that fringed its edge.

Just as the golden glow of the cedars in the upland pasture had seemed to come all of a sudden, as if turned up by the pressure of a button which made electrical connection, and set the machinery of fantasy at work, so the inner swamp suddenly grew all sun-stricken with the yellow of the spicebush bloom. Bare twigs bore clusters of it everywhere, and its intoxicating odor thrilled all my senses with rich dreams of June.

So all this day of passing April the sun shone in the placid heart of the little cove with the full fervor of summer. The leopard frog throated his dreamy yawn from the bog, and the rich, soft perfume of the spicebush seemed to wrap all the senses in longing that thrilled and disquieted even while it lulled. There is a call to vagabondia in the odor of the spicebush, that gipsy of the wilder wood, which finds ready echo in the hearts of us all. If it bloomed the year round there would be no cities.

While I breathed the witchery to the full there fell from the sky above a gentle call, a single bird note out of the blue, that made me sit up straight and look eagerly.

A swift wing stabbed the air above the tree tops, and the note sounded nearer. “Quivit, quivit,” it said in liquid gentleness, and the first barn swallow of my season slipped down toward the pond and skimmed the surface in graceful flight. May is welcome. She could be ushered in by no sweeter music than the gentle call of the barn swallow, nor could she send before her more dignified couriers than the glowing pasture cedars or more richly sensuous odors than that of the spicebush which makes all the swamps yellow with sunshine in her honor.