THE VANISHING NIGHT HERONS

IT is a long time since I have set eyes, in broad daylight, upon the black-crowned night heron, often known as “quawk,” and otherwise derisively named by the impuritans. The scientists have also, it seems to me, joined in this derision, for they have dubbed him Nycticorax nycticorax nævius, which is a libel on his language. At any rate, it sounds like it. The roots are evidently the same.

Yesterday, however, in broad daylight, I saw two pair sailing down out of the sunlit sky to light on a tree by the border of the pond. Very white they looked in the glare of day, and I wondered at first if four snowy egrets had not escaped the plume hunters after all and fled north for safety. Probably I shall never see snowy egrets again, though they used to stray north as far as this on occasions. Now, even the night heron, which used to nest hereabout in colonies of hundreds, is rarely seen.

I suppose if bird species must become, one by one, extinct, we can as well afford to lose the night heron as any. He is not a particularly beautiful bird in appearance, though these four seemed handsome enough as they sailed grandly down into the trees on the pond border. His voice is unmelodious. Quawk is only a convenient handle for his one word. It should rather be made up of the roughest consonants in the language, thrown together with raucous vigor. It sounds more like “hwxzvck!” shot into the mud out of a damp cloud. The voices of night herons, sailing in companies over the marshes and ponds used to sound like echoes of a convocation of witches, falling through damp gloom as broomstick flights went over. Shakespeare named a witch Sycorax. He may have been making game of herons.

To-day, having seen these four, I went down to the places which used to be the old-time haunts of night herons, and looked carefully but in vain for traces of their presence. It is their nesting time. There should be eggs about to hatch, or young about to make prodigious and ungainly growth in singularly flimsy nests that let you see the blue of the eggs faintly visible through the loosely crossed twigs against the blue of the sky. These I did not find, and the big cedars which used to be so populous were lonely enough.

Once there would be a nest in every tree, two-thirds of the way up, and a big heron sitting on guard at the top of the tree, or astride the eggs on the nest itself. How the long legged mother bird could sit on this loose nest and not resolve it into its component parts and drop the two-inch long eggs to destruction on the peat-moss beneath is still a mystery to me. But she could do it, and the young after they were hatched did it, sometimes six of them, and the nests remained after they were gone, in proof of it. Most birds’ nests are marvels of construction; the black-crowned night heron’s seems a marvel of lack of it, but I think few of us could make so ill a nest so well.

The night heron’s day begins at dusk and ends, as a rule, at daylight. His eyes have all the night-seeing ability of those of the owl, and he finds his way through fog and darkness, and his food as well. Yet the bird seems to see well enough by day. The four that sailed down to the pond yesterday in the full glare of the afternoon sun had no hesitation about their flight. They swung the corner of the wood and lighted on limbs of the trees with as much directness and certainty as a hawk might. Indeed, when their voracious young are growing up they have to fish night and day. It seems to me that fish must be becoming more plentiful now that the black-crowned night herons are few in number, for a single bird must consume yearly an enormous quantity.

I undertook the care and feeding of two once that I had taken from one of those impossible nests. They were the most solemnly ridiculous young creatures that were ever made. “Man,” says Plato, “is a featherless biped.” So were these youthful night herons. They were pretty nearly as naked as truth and might have passed for caricatures of the Puritan conscience, for they were so erect they nearly fell over backward.

They would not stay in any nest made for them, but preferred to inhabit the earth, usually just round the corner of something, whence they poked weird heads with staring eyes that discountenanced all creatures that they met. The family cat, notoriously fond of chicken, stalked them a bit the first day that they occupied the yard. At the psychological moment, when Felis domesticatus was crouching, green eyed, for a spring, the two gravely rose and faced her. She took one look at those pods of bodies on stilts, those strange heads stretched high above on attenuated necks, and faced the wooden severity of their stare for but a second. Then she gave forth a yowl of terror and fled to her favorite refuge beneath the barn, whence she was not known to emerge for a space of twenty-four hours.

There was something so solemn, so “pokerish,” so preternaturally dignified about these creatures that they seemed to be out of another, eerier, world. If we ever get so advanced as to travel from planet to planet I shall expect to find things like them peering round corners at me on some of the out-of-the-way satellites, the moons of Neptune, for instance.

Most young birds will eat what you bring them and clamor for more until they are full. These young herons yawned at my approach as solemnly as if they were made of wood and worked by the pulling of a string. Never a sound did I know them to make during their brief stay with me, but they would stand motionless and silent and gape unwinkingly till a piece of fish was dropped within the yawn. Then it would close deliberately and reopen, the fish having vanished. Fish were plentiful that year and so seemed to be time and bait, and I became curious as to the actual capacity of a growing night heron. I could feed either one till I could see the last piece still in the back of his mouth because there was standing room only. Yet if I went away but for a moment and came back, there they stood, as prodigiously empty as ever. The thing became interesting until I began to discover assorted piles of uneaten fish about the yard, and watching soon showed what was happening.

Foot passengers out in the country have a motto which says, “never refuse a ride; if you do not want it now you may need it next time.” This seemed to be the idea which worked sap-wise in the cambium layers of these wooden young scions of the family Nycticorax nycticorax nævius. They never refused a fish. As long as I stood by, their beaks, having closed as well as possible on the very last piece required to stuff them to the tip, would remain closed. After they thought I had gone away they would stalk gravely round a corner, look over the shoulder with an innocence which was peculiarly blear-eyed, then, believing the coast clear, yawn the whole feeding into obscurity in the tall grass. Then they would stalk meditatively forth with hands clasped behind the back, so to speak, and gape for some more.

This was positively the only thing they did except to wait patiently for a chance to do it again, and I soon tired of them and took them back to the rookery, where they were received and, so far as I could see, taken care of, either by their own parents or as orphans at the public expense. It all seemed a matter of supreme indifference to these moon-hoax chicks. There is much controversy as to whether animals act from reason or from instinct. I am convinced that these young night herons contained spiral springs and basswood wheels and that thence came their actions. Probably had I looked them over carefully enough I should have found them inscribed with the motto, “Made in Switzerland.”

I fancy many people confound the night heron, known to them only by his wildwitch cry, voiced as he flies over their canoe in the summer dusk, with the great blue heron, which is nearly twice as big a bird. Perhaps I would better say twice as long, in speaking of herons, for bigness has little to do with them. I well remember my amazement as a small boy, coming out of the woods onto the shore of the pond with a big muzzle-loading army musket under my arm—my first hunting expedition—and scaring up a great blue heron.

I had been reading the “Arabian Nights,” and knew that the roc was a great bird that darkened the sun and carried off elephants in his talons. Very well, here was the very bird in full flight before me, darkening the entire cove with his wings. Es-Sindibad of the Sea might be tied to the leg of this one for aught I knew. Mechanically the old musket came to my shoulder and roared, and when I had picked myself up and collected the musket and my senses, there lay the bird on the beach, dead. But he was still an “Arabian Nights’” sort of a bird for one of his dimensions had vanished, his bulk. He was all bill, neck, legs, and feathers, the wonder being how so small a body could sustain such a spread.

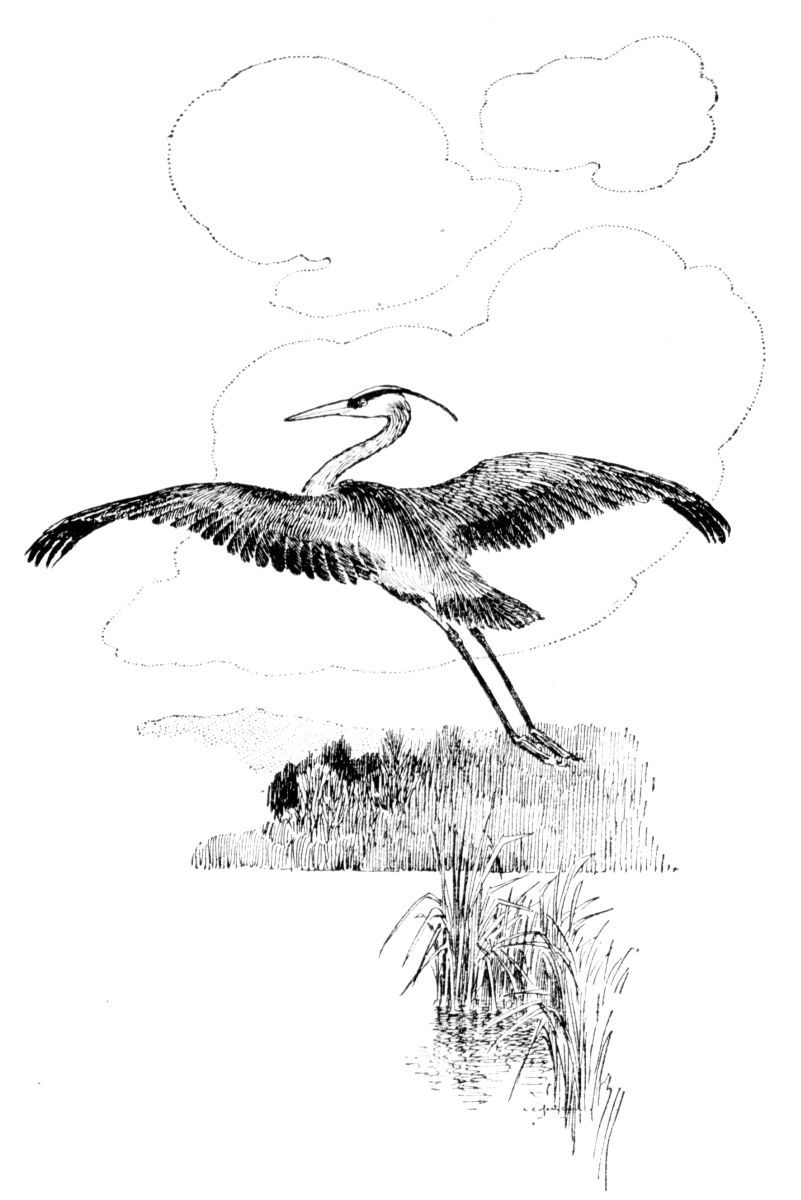

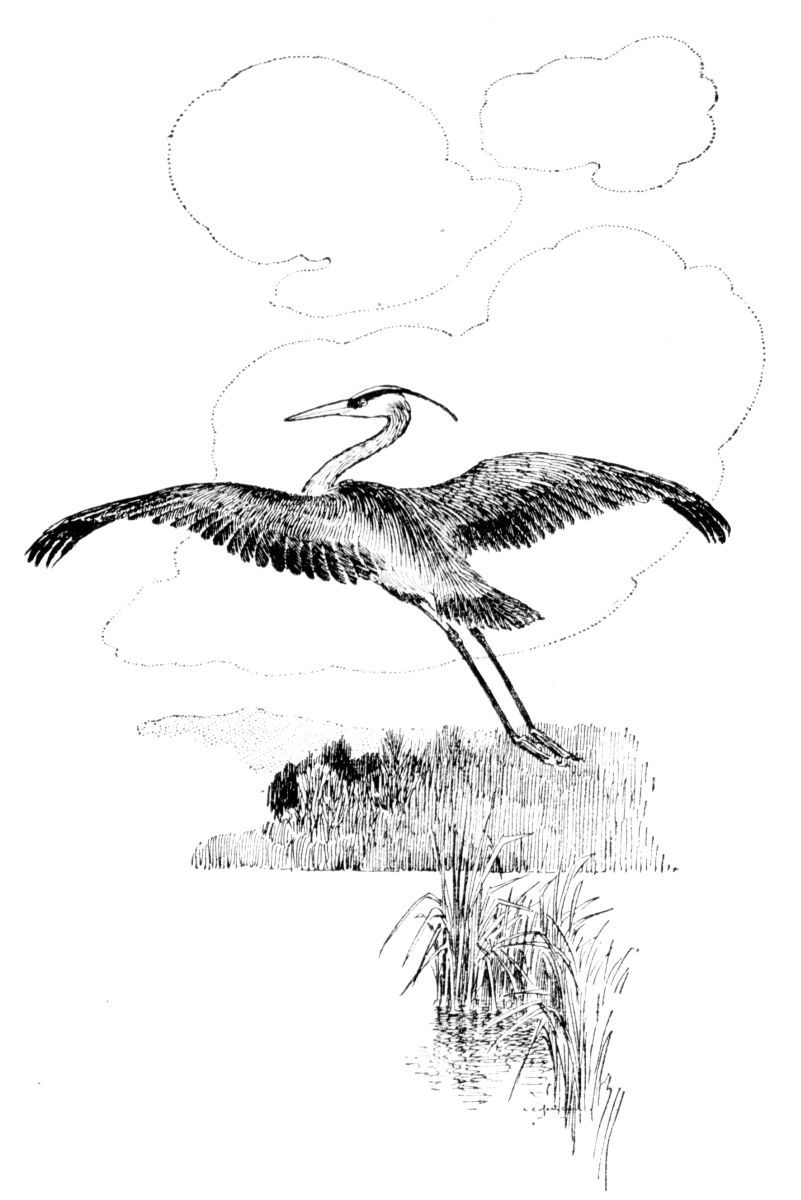

The great blue heron, in spite of his slenderness, which you can interpret as grace or awkwardness, as you will, is a beautiful bird and a welcome addition to the pond shore, the sheltered cove or the sheltered brookside pool which he frequents. If you will come very softly to his accustomed stand you may have a chance to see him sit, erect and motionless, the personification of dignity and vigilance. The very crown of his head is white, but you are more apt to notice the black feathers which border it and draw together behind into a crest which gives a thought of reserved alertness to his motionless pose.

The general impression of his coloring is that of a slaty gray, this melting into brownish on his neck and being prettily touched with rufous and black on other parts of the body. It is a pleasure to watch his graven-image pose, but it is an even greater one to see him take flight. His long legs bend under him, and he springs forward into the air in a mighty parabola. The wings arch in similar curves and lift him with the very first stroke seemingly a rod in air, and as they arch forward for the second the long outstretched neck draws back and the long legs trail in very faithful reproduction of the ornamentation on a Japanese screen. You hardly feel that here is a living creature, flying away from fear of you. It is rather as if a skillful decorator had magically painted the great bird in on the drop scene in front of you. But the flight of the great blue heron is strong if his body is small in comparison with his other dimensions, and he rapidly rises in the majesty of power and flaps out of sight over the tree tops.

The wings arch in similar curves and lift him seemingly a rod in air

The great blue heron is not rare, but I think he, too, is much less common than he used to be. Usually he does not summer with us, going farther north, where he nests in colonies. I seem to find him most often in late September or October, when he drops off for a few weeks, a pleasant fishing trip interlude in his flight to winter quarters in the south. But he is here now, and may be met with on most any May morning if you will seek out his haunts.

Fully as common but by no means so noticeable is our little green heron, the third species of the genus that one is apt to see hereabouts. You will usually pass him unnoticed as he sits all day long in the shadow on a limb near the shore. Nor will you be apt to see him until he becomes convinced that you are about to approach too near. Then, with a little frightened croak, that is more like a squeak, as if his hinges were rusty, he springs into the air, flutters along shore a few rods and disappears into the woods again.

The thought of this little fellow always brings to my mind the silent drowse and quivering heat of August afternoons along a drought-dwindled brook where cardinal flowers lift crimson plumes on the margin of the still remaining pools. Here where deciduous trees shade the winding reaches he loves to sit and wait for the cool of evening before dropping to the margin and hunting his supper.

I always suspect him of being asleep there with his glossy black head thrust under his green wing. That would give him an excuse for being surprised at close quarters and account for his vast alarm when he does see you. If not I think he would slip quietly away before you got too near as so many birds do that see you in the woods before you see them. But perhaps not; perhaps he trusts to luck and hopes till the very last that you will pass on and leave him to watch his game preserves in peace and decide which fishes and frogs he will find most appetizing. The little green heron is a solitary bird, a very recluse in fact, and I do not recall ever seeing two together. He is a nervous chap, after you have once flushed him, however, and if you watch his flight with care you may see him light, stretch his head high to see if you are following him, meanwhile nervously twitching his apology for a tail.