SOUTH RAIN

THE night was dark and bitter cold, though it was early March. Over in the dismal depths of Pigeon Swamp, where no pigeons have nested for nearly a half century though it is as wild and lone to-day as it was when they flocked there by thousands, a deep-toned, lonely cry resounded. It was like the fitful baying of a dog in the distance, only that it was too wild and eerie for that. Then there was silence for a space and an eldritch screech rang out.

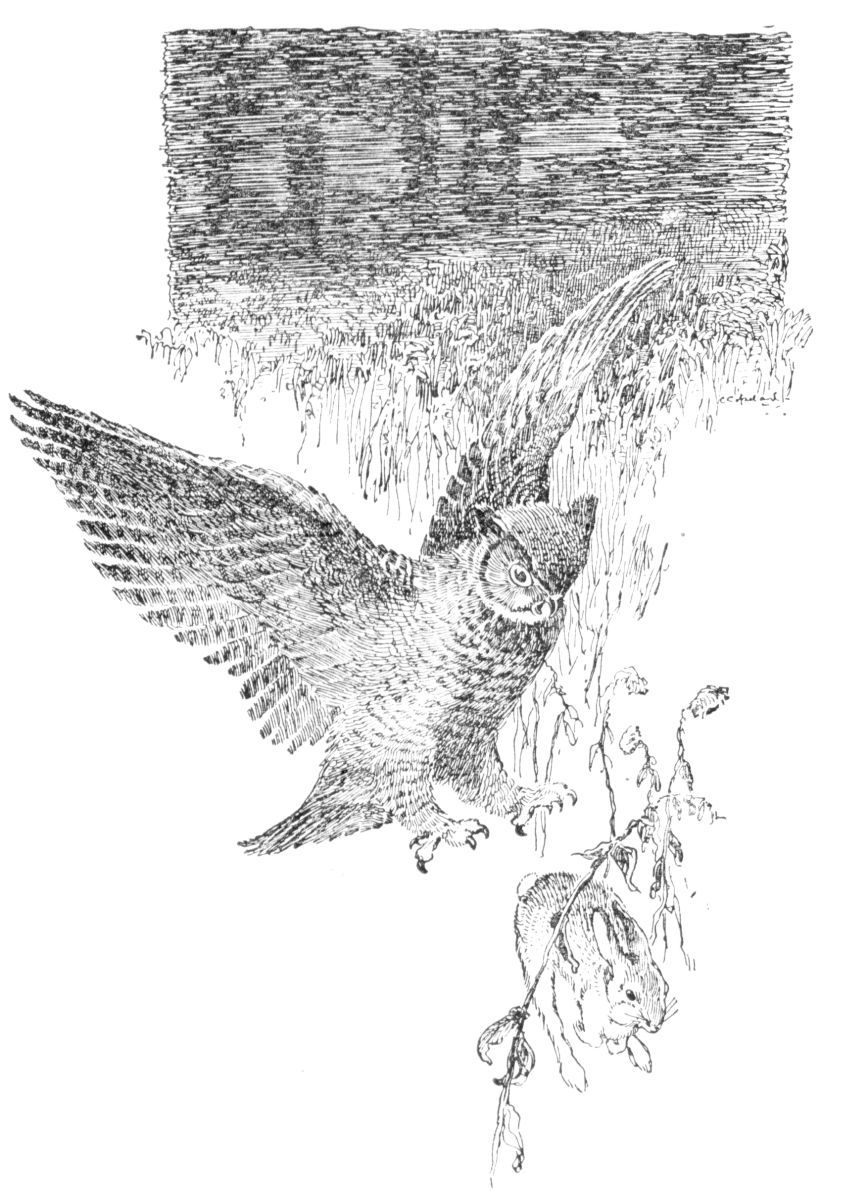

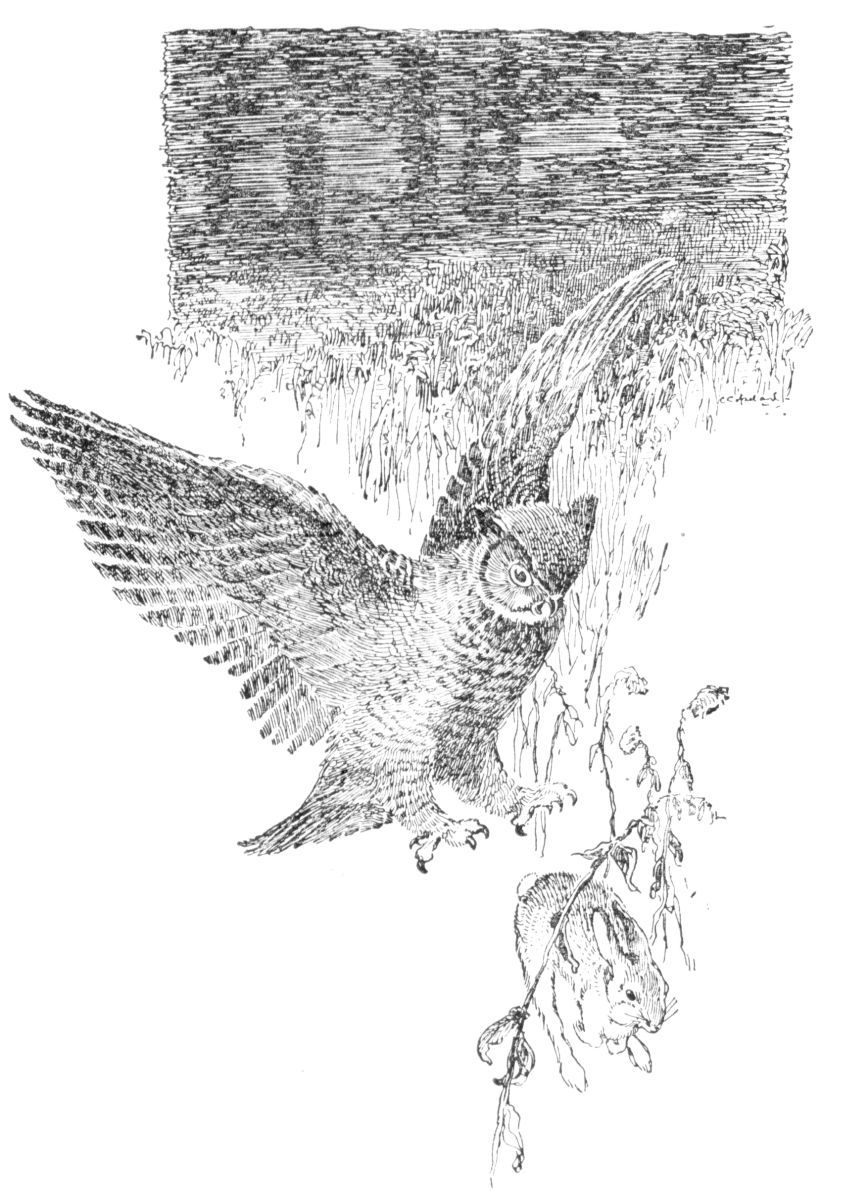

It was blood-curdling to a human listener, but it was reassuring to the great horned owl snuggling down on her two great blotched eggs to keep them secure from the cold, for it was the voice of her mate hunting. Sailing silently on bat-like wings he was beating the open spaces of the wood, hoping to find a partridge at roost, and I fancy the deep “whoo; hoo, hoo, hoo; whoo, whoo,” all on the same note, was a grumble that trained dogs and pump-guns are making the game birds so scarce. Perhaps that blood-curdling screech was one of triumph over the sudden death of a rabbit, for Bubo virginiana is tremendously rapacious and will eat any living thing which he can carry away in his claws.

It might, too, have been his method of expressing ecstasy over the nest and the promise of spring which the horned owl alone has the courage to anticipate with nest-building in these raw and barren days, when winter seemingly still has his grip firmly set on us. Oftentimes his housekeeping arrangements are completed by late February. No other bird does that in Massachusetts, though farther north the Canada jay also lays eggs about that time, way up near the Arctic Circle where the thermometer registers zero or below and the snow is deep on the ground.

That blood-curdling screech was one of triumph over the sudden death of a rabbit

On what trees he cuts the notches of the passing days I do not know, but surely the horned owl’s almanac is as reliable as the Old Farmer’s, and he knows the nearness of the spring. I dare say the other birds which winter with us know it too, though not being so big and husky they do not venture to give hostages to the enemy quite so early in the season. The barred owls will build in late March, and soon after April fool’s day the woodcock will be stealing north and placing queer, pointed, blotched eggs in some little hollow just above high water in the swamp.

The crows are cannier still. You will hardly find eggs in their nests hereabouts before the fifteenth of April, and you will do well to postpone your hunting till the twenty-fifth. Yet they all know, as well as I do, when the spring is near, and I think I have the secret of the message which has come to them. It is not the fact that a south wind has blown, for this may happen at any time during the winter, but it is something that reaches them on the wings of this same south wind.

This night on which the horned owl of Pigeon Swamp brooded her eggs so carefully was lighted by the moon, but toward midnight a purple blackness grew up all about the still sky and blotted out all things in a velvety smear that sent even Bubo to perch beside his mate. There was then no breath of wind. The faint air from the north that had brought the deep chill had faltered and died, leaving its temperature behind it over all the fields and forest. The air stung and the ground rang like tempered steel beneath the foot, yet you had but to listen or breathe deep to know what was coming. The stroke of twelve from the distant steeple brought a resonance of romance along the clear miles and the air left in your nostrils a quality that never winter air had a right to hold. To one who knows the temper of the open field and the forest by day and night the promise was unmistakable, though so subtle as to be difficult to define.

Whether it was sound or smell or both I knew then that a south wind was coming, bearing on its balmy breath those spicy, amorous odors of the tropics that come to our frozen land only when spring is on the way. The goddess scatters perfumes from her garments as she comes and the south wind catches them and bears them to us in advance of her footsteps. You may sniff these same odors of March far offshore along the West Indies,—spicy, intoxicating scents, borne from the hearts of tropic wild-flowers and floating off to sea on every breeze.

With them floats that wonderful grape-bloom tint that touches the surface of all the waters to northward of these islands with its velvety softness, the currents carrying it ever northward and eastward, sometimes almost to the shores of the British Isles. You may see it all about you in mid-ocean as your vessel steams from New York to Liverpool or Southampton or Havre or the Hook of Holland. Some essence of all this gets into the air on the southerly gales that are borne in the windward islands and whirl up along our coast to die finally in Newfoundland or Labrador or Greenland itself. I believe the horned owl knows it as well as I do and begins his nest-building at the first sniff.

At daybreak the wind had begun to blow, all the keen chill was softened out of the air, and blobs of rain blurred the southern window panes. The temperature had risen already above freezing and was still on the upward path. There was in all the atmosphere that rich, cool freshness that comes with rain-clouds blown far over seas. It is the same quality which we get in an east rain, but it had in it also that suggestion of spiciness and that soft purple haze which drifts away from the tropic islands that border the Caribbean. Stopping a moment in my study before going out into this, I found another creature that had felt the faint call of spring and answered it, I fear, too soon. This was a great Samia cecropia moth. The night before he had been safely tucked away in his cocoon over my mantel, where I had hung it last December.

In the night he had answered the call and now was perched outside his cell, gently expanding his wings with pulsing motions that seemed tremulous with eagerness or delight. I noted the soft delicacy of the coloring in his rich, fur-surfaced body and wings, shades which are reds and grays and browns and ashes of roses, and a score of others so dainty and delicate that we have no words to describe or define them.

A wonderful creature this to appear in a man’s house, sit poised on his mantel and blink serenely at him, as if the man himself were the intruder and the room the usual habitat of creatures out of fairy-land. I studied him carefully, thinking, indeed, that he might vanish at any moment, and then I went out into the woods in the soft south rain, only to find that his colors that I thought so marvelous in the shadow of the four walls of my room were reproduced in rich profusion all about me.

His velvety-white markings, lined and touched off with brown so deep in places as to be either purple with density or black, were those of the birch trunks all about me, and there were the rufous tints that shaded down into pearl pinks and lavender all through the groups of distant birch twigs. His gray fur was the softest and richest of the fur of the gray squirrels, and this gray again shaded into red in spots that could be matched only by the fur of the red squirrel. There were soft tans on him of varying shades, from rich to delicate pale, and all the last year’s leaves and grasses had them. Nor was there a color about him which was not matched and repeated a thousand fold in bark and twigs and lichens and shadows all through the wood.

I had but to stand by with the great moth in my mind’s eye to see the whole woodland bursting from its cocoon and spreading its wings for flight. As a matter of fact that is what it is going to do later—but the time is not yet. Meanwhile the south rain was washing its colors clear and laying bare their bright beauty. In it you saw without question the promise of new growth and new life. Trees and shrubs stood like school children with shining morning faces, newly washed for the coming session. All trace of dinginess was gone. The yellow freckles on the brown cheeks of the wild cherry gleamed from far; the pale, olive green tint of the willow’s complexion was transparent in its new-found brilliancy.

Looking down on the ruddy glow of healthy maple twigs, it seemed as if they should have yellow hair and sunny blue eyes, so rich is the coloring of these Saxons of the wood and so fresh it shone under the ministering rain. Even the dour scrub oaks, surly Ethiopians, were not so black as they have been painted all winter, but lost their ebon tint in a hue of rich dark green that was a pleasing foil to the cecropia-moth beauty of the rest of the woods.

The one color lacking was blue. The sky’s leaden gray was but a foil for the rich woodland tints, and I wandered on seeking its hue elsewhere. Over on the hillside are the hepaticas. Their color when open is hardly blue, being more often purple or even lavender, yet they would do, lacking a more pronounced shade. But I could not find a hepatica in bloom as yet. Their tri-lobed leaves are still green and show but little the wear and tear of the winter’s frosts and thaws. In the center of each group is the pointed bud that encloses the furry blossoms, itself as softly clad in protecting fur as the body of my moth visitor, but no hint of color peeped from it as yet. You need to look carefully in very early spring to be sure of this, too; for the hepatica is the shyest of sweet young things, and when she first blooms it is with such modesty that you have to chuck the flower-heads under the chin to get a glimpse even of their eyes. Later on the coaxing sun reassures them and they stare placidly and innocently up to it like wondering children.

Over on the sandy southern slope there might be violets, too. Later in the year the whole field will be blue with them and all about are their rosettes of sagittate leaves, which the cold has had to hold sternly in check to keep them from growing the winter through. Indeed, I do not believe it has fully succeeded. It has been a mild season, and I think the violets have taken the opportunity during warm spells of several days’ duration to surreptitiously put forth another leaf or so in the very center of that rosette. If so, they might well have followed this courage with the further audacity of buds, and buds, indeed, they had but not one of them was open far enough to show even a faint hint of the blue that I was seeking.

It was hardly to be expected of the violets. They are so sturdy and full of simple, homely, common sense that it is rare that you find them doing things out of the usual routine. Warm skies and south winds may tease them long before they will respond by blooming earlier than their wonted date. They know the ways of the world well and realize how unwise it is for proper young people to overstep the bounds of strict conventionality. On the other hand, the hepaticas, with all their innocence, perhaps because of it, care little for the conventions. Indeed, I doubt if they know there are such things, or if they have heard of them would recognize them. It is likely that in some sunny, sheltered nook some rash youngster, all clad in furs of pearl gray, is in bloom now, though so shy and so hidden that I was unable to find the hint of color. I have known them to half-open those lavender-blue eyes under the protecting crust of winter snow.

Toward nightfall the rain ceased and the clouds simply faded out of a pale sky, letting the sun shine through with gentle warmth. Whither the mists went it was hard to tell, but they were gone, and a soft spring sun began wiping the tears from all things. Under its caress it seemed as if you could see the buds swell a little, and I am quite sure, though I was not there to see, that at this moment the willow catkins down by the brook slipped forth from their protecting brown sheaths and boldly proclaimed the spring.

They might have done so, and I would not have seen had I been there, for just then I had a message. “Cheerily we, cheerily we,” came a faint voice out of the sky. An echo from distant angel choirs practicing carols for Easter could not have seemed more musical or brought more delight to me down at the bottom of the soft blue haze that was taking golden radiance from the setting sun. Up through it I looked to the pale blue of the sky and saw two motes dancing down the sunshine,—motes that caroled and grew to glints of heavenly blue that fluttered down on an ancient apple tree like bits of benediction.

Just a pair of bluebirds, of course, and I don’t know now whether they are the first of the migrants to reach my part of the pasture or whether they are the two that have wintered here and that I have seen before on bright days. Wherever they came from they supplied the one bit of blue that I had sought, and their presence was like an embodiment of joy. Then the gentle prattling sweetness of their carol; what a range there was between that and the wild voice of the great-horned owl, heard not twenty-four hours before! It was all the vast range between Arctic winter night and soft summer sunshine. The owl had voiced the savage grumble of the winter, the bluebird caroled the gentle promise of the spring.

The promise may be long in finding its fulfilment, of course. The snow may lie deep and the frost nip the willow catkins,—though little they’ll care for that,—and the bluebirds may be driven more than once to the deep shelter of the cedar swamp, but that does not take away the promise that came on the wings of the south wind,—the promise that set the great horned owl to laying her eggs in that abandoned crow’s nest, and that made the bluebirds seek the ancient apple tree as their very first perch. March is no spring month, in spite of the “Old Farmer’s Almanack.” It is just a blank page between the winter and the spring, but if you scan it closely you will find on it written the promise we all seek,—the hope that lured my great Samia cecropia out of his snug cocoon.