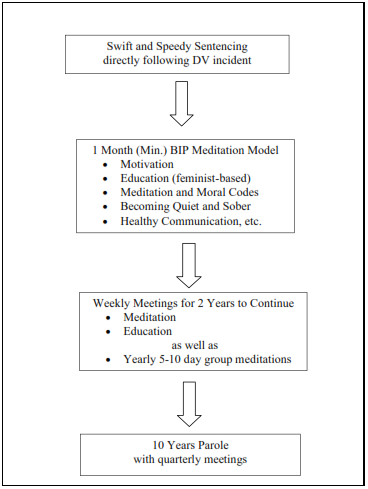

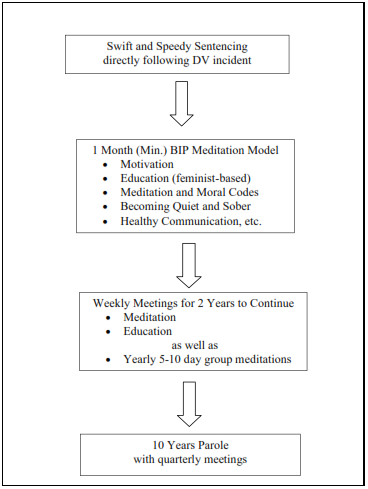

Proposed Model for BIPs that Incorporates Meditation

Looking at the many benefits cited from prison meditation programs and the mental and neuro-physiological impacts of meditation, and based on the theoretical framework of the complex social dynamics that contribute to domestic violence, while keeping the limitations brought out in the empirical work in mind, I have come up with an outline for a therapeutic contemplative model that BIPs may use in order to incorporate meditation as a tool for rehabilitation. Understanding the negative consequences of gender construction and patriarchy, I agree with the majority of respondents that education and social deconstruction is critical to changing harmful thought patterns that trigger abusive behaviors in batterers. However, although patriarchy and gender construction contribute to the perpetuation of VAW, my argument is that the root cause of suffering is not solely societal, but lies within each individual, as violence is always a choice. Therefore, in order to eradicate VAW, education alone will not suffice. This has been clearly demonstrated in the previously mentioned studies that find BIPs to be ineffective. Thus, a more comprehensive, multi-disciplinary approach is needed that will give batterers tangible tools on how they can transform themselves from the inside. The model I propose provides feminist-based education from the Social and Cultural model along with training in meditation. This proposed hybrid model may work experientially, where education may work intellectually, thus creating a balance and offering batterers tools to transform their violent thought patterns and resulting behaviors. As many respondents recommended, it shall include education on healthy relationships, communication, socialization, gender construction, masculinity, accountability, as well as different moral philosophies that will supplement meditation practices. This alternative model is intended to meet existing state standards, however, due to time and word limitation, it will not be presented as an official proposal for a BIP program, but rather as a suggestion of what can be done.

Since ridding batterers of harmful beliefs about male dominance entails education and perhaps a re-wiring of brain patterns, transformation will require a substantial amount of time and effort. In fact, S.N. Goenka refers to meditation as a “spiritual surgery.” Therefore, I recommend that BIPs conform to standards such as those used for many alcohol and drug-abuse rehabilitation programs, where individuals must remain 24 hours a day for a minimum of one month. This could happen in jail, such as the previously mentioned programs through the SFSD and TCSD. The idea is that with a concentrated block of time away from societal distractions, batterers can unlearn (or deconstruct), harmful social attitudes, while at the same time meditating in order to discover their sensations to gain greater control over their minds and reactions. Essentially, they will have the time and space to become acquainted with their true selves.

As found in the empirical section, mediation will not work for everyone, as not everyone will accept the idea of meditating. Thus, the program would also offer a feminist social-cultural BIP model, concentrating on the power and control wheel, the equality wheel, etc., with group discussions and a focus on accountability. Healthy communication techniques would be taught and practiced, with an emphasis on conscious breathing and awareness of sensations. Moreover, the program should provide a psychologist to work with batterers individually to see to any psychological needs, such as past traumatic experiences, etc., a concern that emerged in the empirical portion of this paper. Programs that wish to incorporate additional holistic healing methods, such energy work, hypnosis, etc. may choose to offer such tools depending on the needs of the individual, as I agree with several of the respondents who shared that every batterer is different and thus a successful rehabilitation program should offer a variety of tools.

Because battering is often a lifelong pattern of coercive behavior and abuse, and not a one-time incident, I recommend that these month-long rehabilitation programs be followed by a two-year program of group meetings every week for four hours or twice a week for two hours a week, with an additional 5 to 10 days of intensive meditation practice in a group setting, such as in Vipassana courses. In addition, I would encourage state requirements to adhere to a swift sentencing for the one month batterer intervention program, including an extended parole period of 10 years, meeting quarterly every year to track their progress and analyze their attitudes and behavior. This would be required for all batterers, even those who are no longer in a relationship with the victim of the catalytic incident.

Also, it is imperative that batterers become motivated to change through understanding their own suffering and the social dynamics that have contributed to their harmful thought patterns and behaviors. Like several respondents commented, I agree that meditation will only work for people who are sincerely willing to practice it because they truly want to change their thoughts and behaviors. Therefore, motivating the batterer to want to change is essential, and education and motivational stories should be shared immediately, prior to starting any formal meditation practice. This initial motivation is key to helping the batterer comprehend his own state of internal suffering. If a batterer understands the many benefits from surrendering harmful thoughts and behaviors, he may be inspired to work towards eradicating his own suffering and achieving and maintaining a state of equanimity and inner peace. Such motivation could consist of the videos, “Doing Time Doing Vipassana,” “Changing From the Inside,” and videos by teachers such as the Maharishi or S.N. Goenka. These videos are often shown in prisons before offering a mediation program, with great results of inspiring inmates to participate. At the same time as breaking down the cultural barriers toward meditation and motivating batterers to want to end their own suffering, (for their own benefit and the benefit of everyone they come into contact with), the programs can use poignant testimonials from ex-abusers and ex-victims (both in person and through videos) to open the batterers up to the idea that their behavior is wrong and that they have the ability to change it. Furthermore, educational videos about the social construction of masculinity, such as those by Jackson Katz can be introduced as the foundation for the social/cultural piece. Other supplemental materials, such as readings and exercises from Paul Kivel's work, could be introduced at this time. The goal should be to educate batterers without putting them on the defensive, which would only create resistance.

Just as many inmates learn how to become “better” criminals in prison, batterers often learn how to become “better” abusers during BIPs. They learn different tactics of abuse, including how to hide their controlling behavior from others and to hit their victims where no one else will see. Corroborating with other batterers who share the same harmful views of women and victims may make them feel indignant and justified in their abuse of others. Therefore, practicing silence, a technique used in Vipassana meditation, may be beneficial for the first week, while the batterers are adjusting to the program. This first week is also a crucial time for those with substance abuse issues. During this time they can focus on observing and listening, slowly breaking the barriers and motivating them to focus on what is going on in their minds and bodies.

Moral rules should be strictly observed during this time period, among them absolutely no intoxicants, including caffeine and cigarettes. In that way the program will act not only as a BIP but as a drug and alcohol rehabilitation, for those batterers who also have issues with substance abuse. I recommend that programs also only offer simple vegetarian food, which will help cleanse and purify the participants. These rules will undoubtedly cause resentment in many batterers, which must be met with patience and compassion. Penetrating the tough and unwilling exterior and motivating a batterer to desire positive, nonviolent transformation may be the biggest challenge to the overall success of the program. It is therefore strongly recommended that all staff members (including prison staff, if based in prison) become proficient in meditation. This will help create a safe environment where the batterers feel they are being treated as humans (which may hinder their desire to dehumanize others). This method worked well for Tihar Jail, as it was found to aide the cultivation of compassion for prison personnel towards inmates.

As respondents suggested, programs would benefit from both group meditation, where all practitioners are using the same method, and solitary meditation, where the practitioner could choose from different styles learned from meditation teachers. A variety of meditation styles could be used to accomplish the goal of transformation, though programs could work with one style, such as Vipassana or TM. There are styles of meditation, such as Vipassana, that discourage the intermingling of meditation styles. I feel that this program should not be an attempt to “convert” batterers to any one style of meditation, rather, it should be intended to give the individuals experience and options so that they can choose the style that works best for them and that they will be most likely to continue practicing while out of the program. Lastly, the program should incorporate an evaluation system to gauge the programs effectiveness, register best practices, and document case studies.

The logistical concerns would primarily be finding a suitable location, staff members, and funding. However, as RV19 encourages, “Where there is a will, there is a way!” Although funding may be a major concern of the state, the actual costs of DV far outweigh the costs of batterer rehabilitation. The costs of DV include emotional and physical trauma that will negatively affect communities and may also adversely affect future generations. The economic costs of DV are also extreme. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated in a 2003 report, “that the costs of intimate partner violence in the USA alone exceed $5.8 billion per year: 4.1 billion are for direct medical and health care services while productivity losses account for nearly $1.8 billion.”145 Thus, any initial financial costs invested into such a program would cut social costs and prevent further violence for years to come.

Batter Intervention - Meditation Model

Diagram of the Proposed Basics