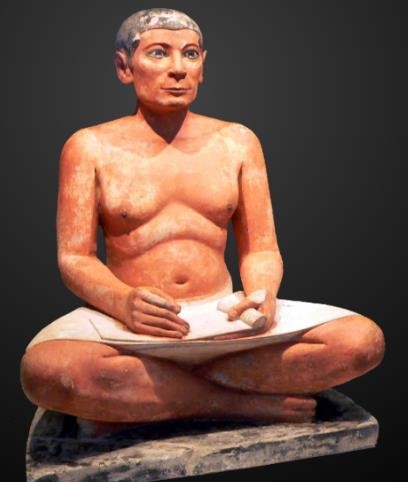

Ancient Egypt – a perfect paradise

Egyptians saw their Empire and world as a perfect paradise and if they lived a good life then in death they would pass to the same paradise. Unfortunately, their life meant that they would make an early trip to that paradise, but it was a good life, supported by a host of Gods.

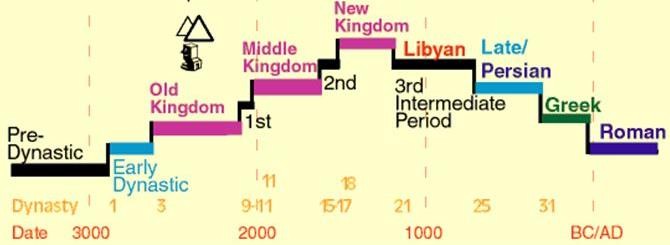

Ancient Egypt was a land of remarkable stability with 3 Kingdoms lasting up to 500 years each with short disruptions, after which life would return to the normal ‘paradise’.

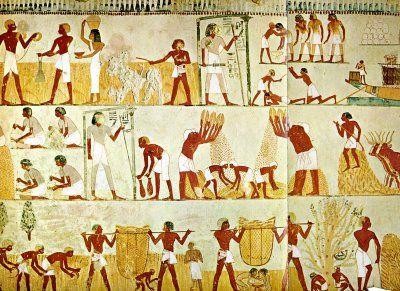

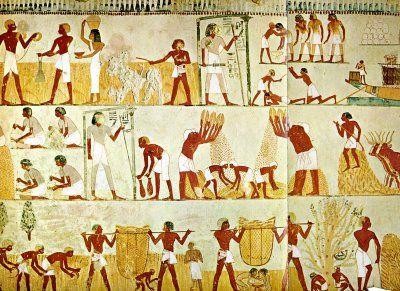

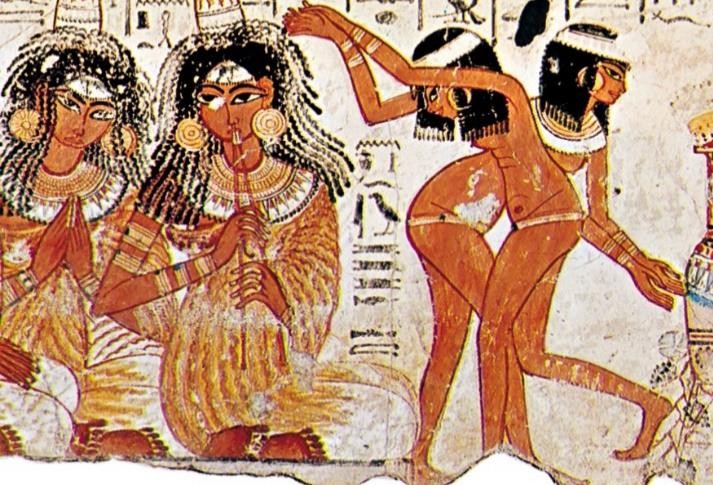

Their frescoes adhere to a strict religious and cultural design, reflecting the unchanging world both now and in the afterlife. Simple lines and flat areas of colour create a sense of order and balance within a composition.

An order and balance fundamental to Egyptian culture, in a society unchanged over 2,000 years. (1)

The Egyptians had a love of life, believing that they lived the best possible life in the best possible of worlds, before and after death. The philosophy was one of living in harmony and in balance with both the community and the world at large. A line from the First Kingdom reads:

Let your face shine during the time that you live. It is the kindness of a man that is remembered during the years that follow

This philosophy applied to all social classes, where all valued life and enjoyed competing in ‘Games’. Board games and sports were popular pastimes and the ‘games’ were often combined with festivals and national celebrations. Field hockey, rowing, javelin, archery and running where - after 30 years of reign - even the Pharaoh was required to prove his fitness by running a measured course. Fitness was important and weekly routines were designed to encourage not just stamina, but team spirit. This healthy life was reflected in cleanliness both in their homes and personally where all bathed regularly, with men shaving their heads and body hair to avoid lice.

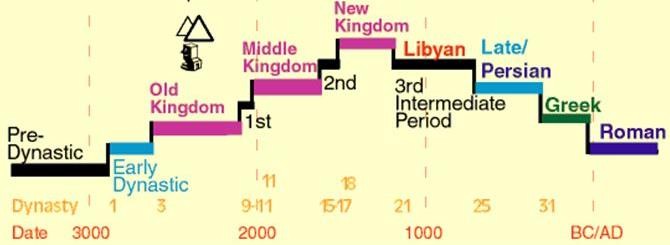

Tomb relief of ploughing, harvesting and threshing.

The vast majority were farmers who worked the fields for the state or landowning local nobles, taking a portion of the cereals for themselves. This was supplemented by growing vegetables alongside their homes and supplemented by fishing, regulated by the state. So, all Egyptians enjoyed a vegetarian diet, supplemented by some poultry and fish, particularly on festival days. The Egyptians believed that humans, animals and plants were one of a whole and an essential element of the ‘cosmic order’.

An agricultural and environmental system which many people advocate today.

Women had total equality in owning a business or land and initiating divorce. While men laboured in the field, women ran the home, including the vegetable plot and making the bread and a honeyed beer – essential staples of people’s lives. The Nile was not clean enough to drink, so a low alcohol beer was consumed by all and ‘inns’ were in every community. People enjoyed their social lives and also feasts and festivals accompanied by music and dance. (2)

Children had pets and toys including puppets, dolls and mobile wooden toys and storytelling of magic, romance and ghosts provided a history. Children ran naked until the age of puberty at 13 for girls and 15 for boys, when they would normally marry. People wore short linen ‘kilts’ that were difficult to dye so most were left in their natural off-white colour and all went barefoot.

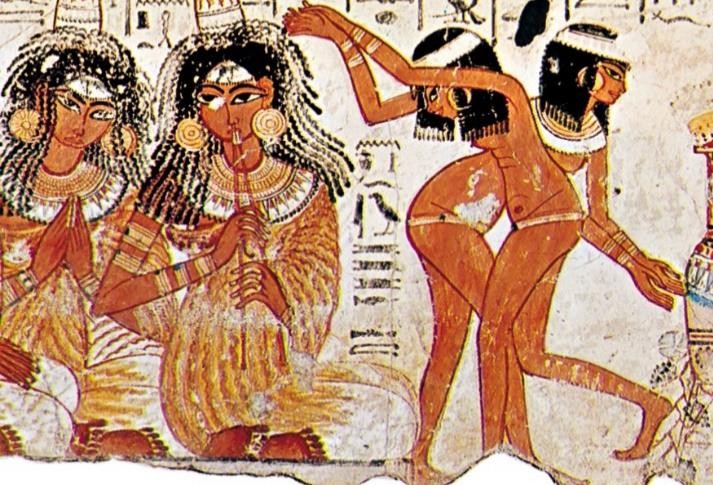

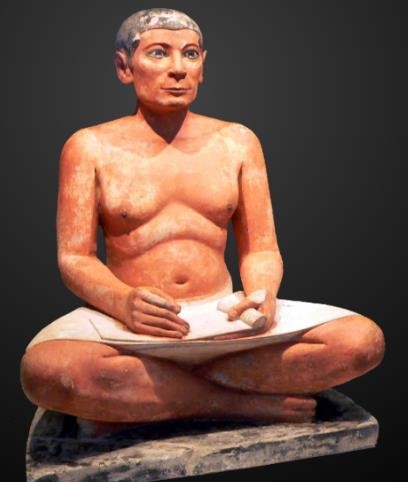

This society ran without coinage, but under a barter system where fixed amounts of agricultural produce could be exchanged into copper, silver or gold. A system that was standardised across Egypt and so which resisted any monetary collapse or inflation and was open to all and supervised by ‘scribes’, who held a respected position in the administrative and legal bodies.

The Seated scribe, Saqqara

Rather than applying written legal statutes, disputes were settled on a common sense view of right and wrong. Punishment was swift and all swore an oath to speak the truth.

Slaves were mostly servants kept but unpaid or captured in battle or were criminals. They could earn money and buy themselves out of servitude to be full members of society. Society ran on native Egyptians, not on slavery.

This perfect life had one underlying fault. With the Nile running at the centre of this tropical country to the north of Africa, disease from parasites such as malaria and worms, threatened all those who worked and played outside. One third of children would die, with their father dying at age 30 and their mother at 35. People died young, although with an unshakeable faith in an afterlife. With a life spent pampered indoors the Upper classes lived longer from age 60 anywhere up to 90, ironically providing the stability in Egyptian society.

This long living upper class (3) could take a longer view and undertake monumental buildings, which are astonishing in the remarkable skill and techniques used by artisans.

Ancient Egypt, Sculpture & Architecture

This sculpture of Pharaoh Khafre was one of 13 that stood in a huge pillared necropolis (funerary city) and is carved from an extremely hard and dark stone, related to diorite. To carve and then polish this stone with only a bronze tool and then grind and polish the surface, is a remarkable achievement, particularly in the symmetry and ideal body proportions. His strong face suppresses all motion to create an eternal stillness, in a controlled empire with powerful leadership. He is portrayed as eternal in the universe that all Egyptians lived, underlining the unchanging nature of life, which encompassed all living things. Here the God Horus was depicted as a falcon, spreading its wings to protect the Pharaoh, in an Egyptian Empire.

Khafre, enthroned, 2570 BC

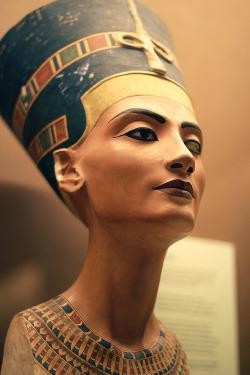

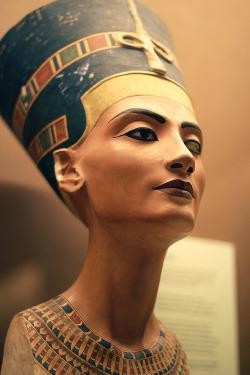

The life size bust of Nefertiti also portrays a timeless beauty that will continue into the afterlife and is still with us today, 3300 years later. The bust shows a symmetry in the lines of the wide hat continuing through the forehead, down to the chin and poised on the delicate neck, much as a flower stem. Nefertiti displays a protective kindness and authority with her chin held high. This beauty and realism are in direct contrast to the religious confines of frescoes.

Egypt abounds with a sense of order and a power that is unchallenged and is displayed in the architectural order of the King’s tomb on the Giza plateau, adjacent to Cairo.

Bust of Nefertiti, 1345BC, Great Royal Wife on the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten

The Giza pyramids were built 4,600 years ago to such mathematical precision, that at 139m high, each base is equal to an error of just 58mm with joints of 0.5mm between each of the 2.9 million two-ton blocks. Over 20 years of building, one would be set every 10 minutes, following a production line of quarrying, shipment and precision cutting. The exterior was clad in highly polished white limestone panels and possibly with a gold capstone. Their past is very sophisticated.

At the same time Northern Europe was building the crude Stonehenge.

Pyramids of Giza, 2589-2504 BC, Pharaoh Khufu

Built over 10-15 years by between 40-100,000 employed workers and artisans, enjoying privileged conditions in an adjacent village and assisted by farmers during the annual flooding of the Nile. To work on any Pharaoh’s tomb or temple, was considered an honour. After Giza, pyramids were built much smaller and later pharaohs were buried in underground tombs in the Valley of Kings, hiding sites from later tomb raiders.

Great temple complexes were built to house a Treasury and a series of tombs, dominated by a temple. The carved columns and painted roofs, hide an underground series of chambers and passages, as in a maze. These are a designed to protect tombs and confuse and trap any prospective robber with 20-ton trapdoors. Historical records tell of a fabled lost network of 200 rooms, yet to be uncovered.

These inspired the garden mazes we have today.

Hypostyle Hall, Temple of Hathor, Dendera, 2250 BC

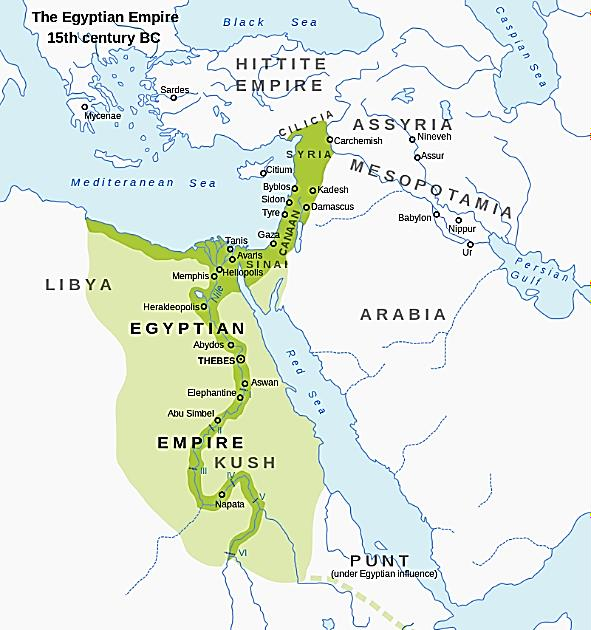

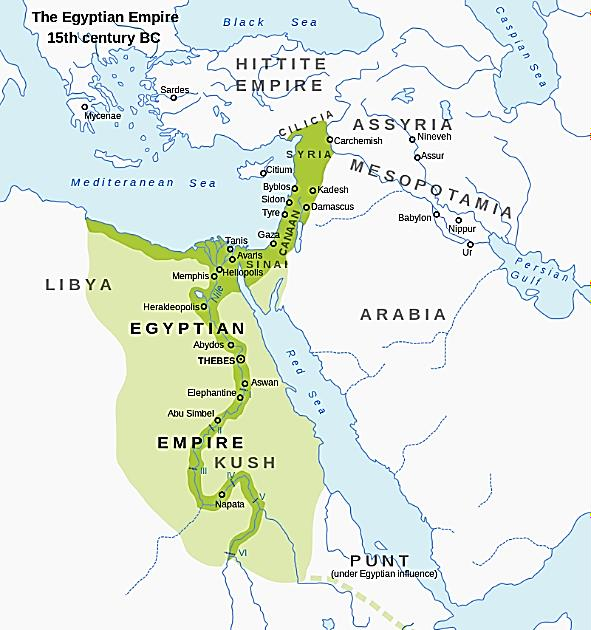

Although trading throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, the Egyptian people were not great travellers, regarding other lands as inferior to their ‘universe’. They traded across the Mediterranean with 43 metre ships exporting grain and linen and bringing back spices, oil and luxury goods, with ebony gold and ivory from Punt. (North Africa) Their military was primarily for defensive purposes and only extended their empire when threatened by countries to the North. But the Egyptian Empire was to eventually decline and be taken over first by the Persians from Arabia, then the Greeks, to be finally absorbed into the Roman Empire. The Greeks in particular frequently visited and took home the architectural temple designs.

Egypt, extent of Empire, 1570-1069BC

Art had underpinned Egyptian society by projecting an unchanging and secure life in which everybody was part, guided by a ruling Pharaoh. Art told their story and was a visible depiction of their culture and beliefs.

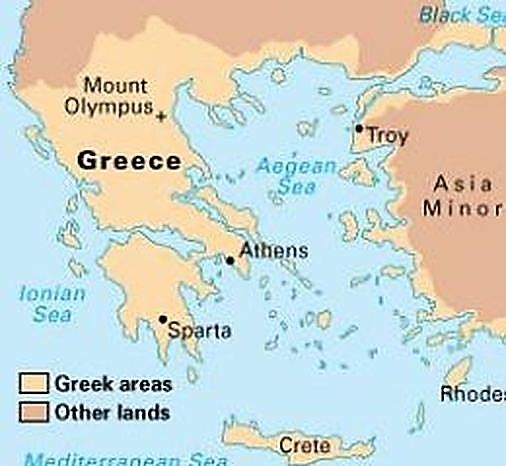

Ancient Greece – Wars

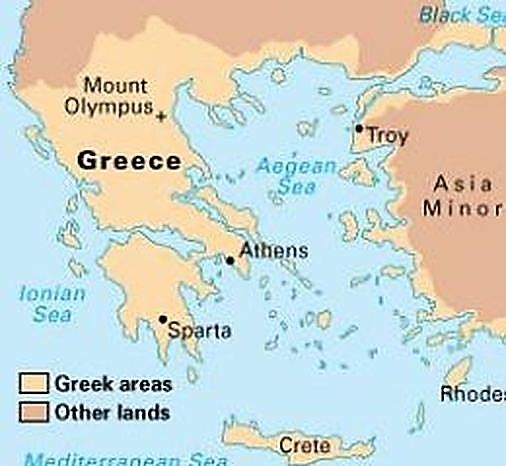

Ancient Greece, land of Gods and wars. For an incredible thousand years, war and peace swept across the lands and seas between Sparta, Athens and Troy and finally facing the Persian Empire. Their world was a mixture of peace and turmoil, of victory and defeat, where the Gods held sway.

Life was dominated by the Greeks’ belief in their Gods overseeing and rewarding their lives, although they did not share the Ancient Egyptian belief in a continued paradise after death. Gods were fundamental to religious culture and life, but it was a male dominated society.

For 500 years the individual city states of Sparta, Athens and Troy fought on land and sea. Greece was a place both of beauty and brutality. Children in Sparta, both rich and poor, were trained for war from the age of seven and later required to serve in the army. Each state was afraid that the other would become too strong and then by monopolising resources, overpower all the states around. During one siege the Spartan warriors were massed at the gates of Athens, but they were never to enter. Each state depended on their harvest to feed their citizens and most people worked in the fields. The warriors were also farmers and had to return home for the harvest!

But threats also came from across the sea where the great Persian Empire in Asia Minor, was massed at the doors and set to invade.

Classical Greece was not to emerge until the Persian threat had been overturned and it would take two great battles for that to happen. Persia invaded in 480BC at the Battle of Marathon where 10,000 Athenians faced some 20,000 Persians and a Persian fleet of 600 ‘triremes’ (galleys) with transport ships for soldiers, horses and provisions.

Great battles at sea would see 170 oarsmen in each galley, smash and crash their great pointed bows into the enemy. On land, their armies would line up to face each other and charge to crash with their shields. Then tear into each other with long spears and use short swords to cut and slash when the spears broke. These were fierce and bloody hand to hand battles.

Although outnumbered 2:1 the Athenians triumphed, surrounding and destroying the Persian army soon after their landing on the beach. Persia’s empire was dealt a mighty blow with a loss of 6,400 men against just 192 Athenians. The runner Phillippides ran the famous 25 miles from Marathon to Athens to announce the victory and with his very last breath exclaimed ‘Joy, we win’ and the legend of the Olympic marathon was born.

10 years later a unified Spartan and Athenian army faced a second even larger Persian force of 100- 150,000, facing just 7,000 Greeks. But superior Greek strategy drew the Persian army into a narrow pass between cliffs and the sea, squeezing the Persians against a Greek wall of bronze shields. They resisted for 3 days, until - with the dead piled high for the Persians to clamber over - just 300 Spartans and 700 Athenians were surrounded by the Persian army in a brave, but futile defence.

Finally beaten, Athens was evacuated and then burned to the ground. But at sea the Greeks had simultaneously trapped and decimated the larger Persian fleet, again by luring them into a narrow stait, cutting off their escape home. With the bulk of their 3,000 transport ships destroyed, the Persian army withdrew on a long overland march home, where most were lost to disease and starvation. Persia never again regained it’s strength. (4)

This great victory left the Greek states to dominate the Eastern Mediteranean, bringing huge trade and great wealth to its people and leading to a unified Empire formed by Alexander the Great. This strength formed the seeds for classical Greece, bringing democracy and the great art and culture that we still admire to this day.

Ancient Greece - The Olympics

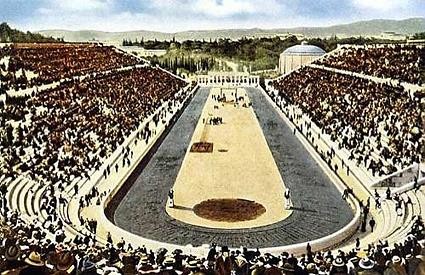

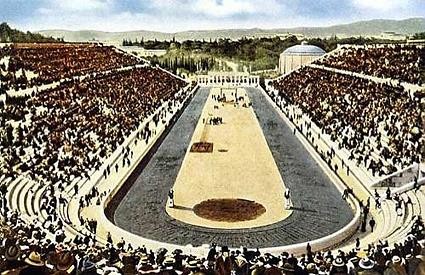

Amazingly there was one thing that would stop all wars – the Olympics! Winning at the Olympic Games was as important as it is today, bringing great fame and prestige and wealth to the athlete and to his home city and state. The greatest games of the ancient world. But to enter each state had to sign a truce that no wars would be fought during the ‘Games’ – sport wins over war! Their dominance was then asserted through sport.

Competitors came from near and far with some making a long journey, including a 2-day boat voyage from the islands and lands around the mainland. In those days, this could be a dangerous voyage with storms driving the boats on to rocks and many drowning.

On arrival the stadium stretched before them, high up in a ravine, in the hills north of Sparta. Under clear blue skies, a white oval with tiers of seats for 50,000 people from all the states. A sea of white robes, all cheering and singing.

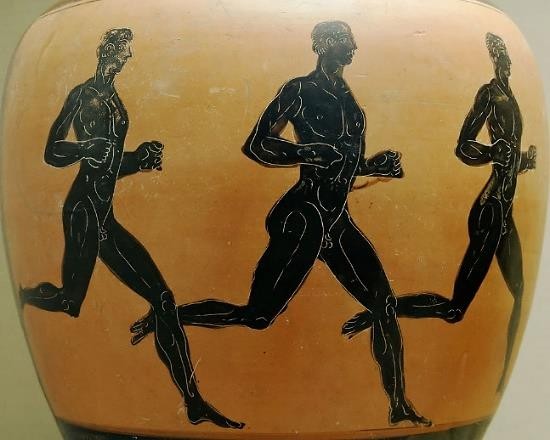

The athletes would line up to enter the arena, each naked and glistening with olive oil rubbed in to their skin to display their muscles. (Women were banned from the stadium, to have their own games) Striding down the entrance steps, through a line of life-size bronze statues celebrating past champions - also polished and shining in the sun - to parade around the arena, as each state cheered their champion. (5)

With the games so important, cheating was banned, as with doping today. Any athlete found cheating would have his name published and shown at the entrance, to the great shame of both himself and of his state. This reinforced the bonds in society and the cultural values of honour and loyalty.

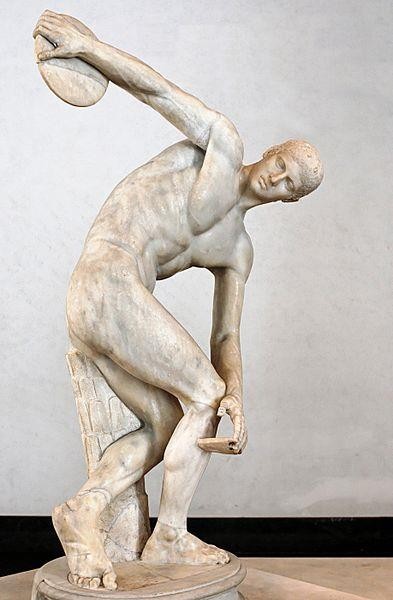

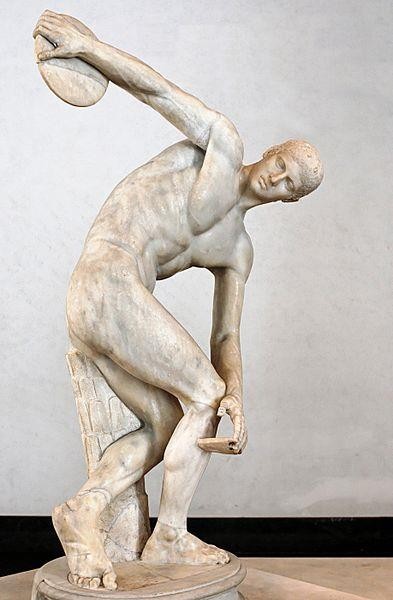

One event was the discus and that can still be seen in one of the statues commemorating a past champion. Today that bronze statue has long gone, but the Romans had made a marble copy known as ‘Discobolus’ – the ‘Discus Thrower’. In the long jump competitors swung two weights in front of themselves, to throw their arms and body further forward. (5)

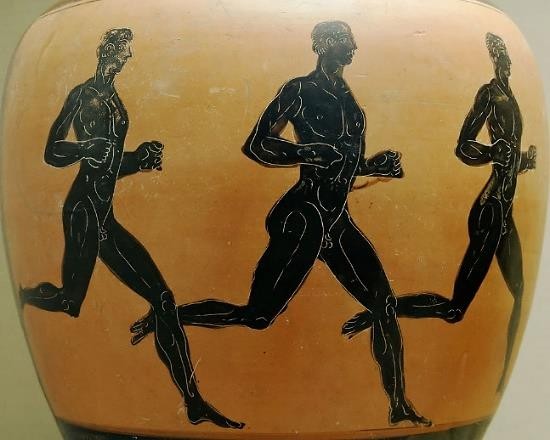

A major aspect of the Olympics was artistic expression, where Greeks described these athletes as ‘beautiful’ and admired their strength and elegance, which reflected their ‘ideal’ culture. Their fame was celebrated on vases and jugs where their balance is artistically portrayed

Discobolus, originally bronze in 450 BC,

Roman copy, British Museum, London

The Games ran from 765BC to 385AD and grew to some 50 events of running, jumping, javelin, boxing and wrestling, with even soldiers in heavy bronze armour running two laps, and the famous chariot races. (5)

All the Greek city states shared a winged goddess of victory called ‘Nike’ who stood at the entrance to the Games.

Now we have running shoes made by ‘Nike’ using the same wing:

Winged Nike, c. 200 BC, Louvre Paris

Philosophy and the Cosmos

Underlying Greek society was the preoccupation with philosophy (meaning a ‘love of wisdom’), that questioned the nature of the world around them and the individual ethics that lead to the best way to live. This freedom of thought and expression gave life to the democracy (meaning ‘people power’) that formed the political and civic institutions, setting the goal of politics and equal justice for all. Our world today owes much to the philosophers who led these discussions, of which three made the greatest and most lasting contributions. (6)

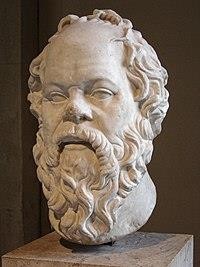

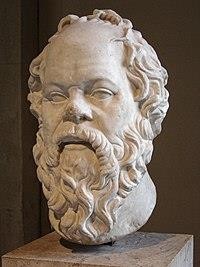

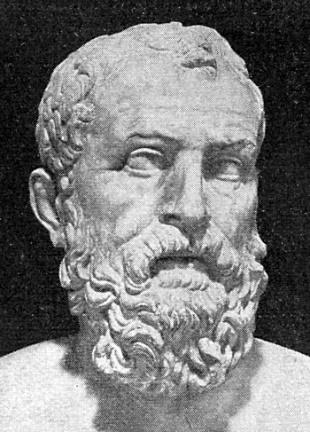

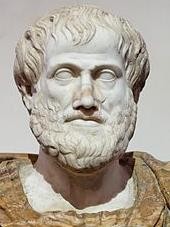

Socrates (470-399 BC) who introduced a form of inquiry where groups of individuals were led through question after question of themselves to realise a clarity of thought through reasoning and logic, questioning your statements to arrive at an informed proposal and so conclusion.

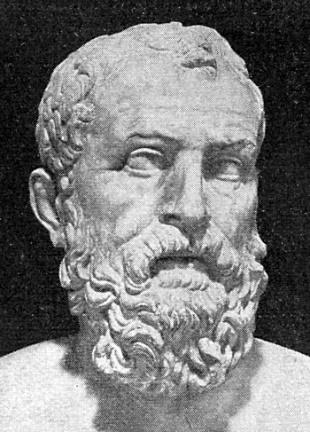

His student Plato (427-347 BC) raised ethical questions as to what is a fulfilling life in an ever-changing world, where everything can so easily be taken away, questioning the sense of permanence that we experience within a reality of change. Separating the mental realm from the pains and changes of the physical world, can lead to lasting values away from material concerns. Plato was to found the Academy of Athens, the first institution of learning in the western world, that was to last almost 1,000 years.

Then Plato’s student, Aristotle (384-322 BC) who looked to better understand the world and how matter is inter- related in different forms. His theory was that substances determined forms, whilst Plato considered that forms determined their substances. For Aristotle ‘substances’; or ‘matter’; are unchanged, whilst the forms they compile, can evolve. But then what comprises ‘matter’?

Other philosophers proposed that matter was comprised of atoms that can neither be created nor destroyed and that collisions of these atoms formed a cosmos consisting of many different worlds, which is infinite and that within this, the earth rotated around the sun. Not a million miles from our discoveries today and without the benefit of telescopes or calculators. ‘Ancient Greece’ was a sophisticated, confident and intellectual society.

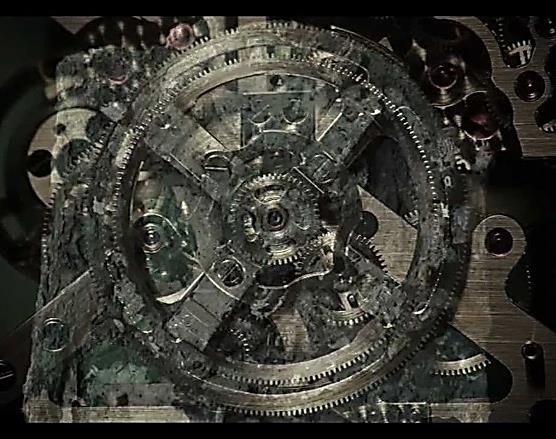

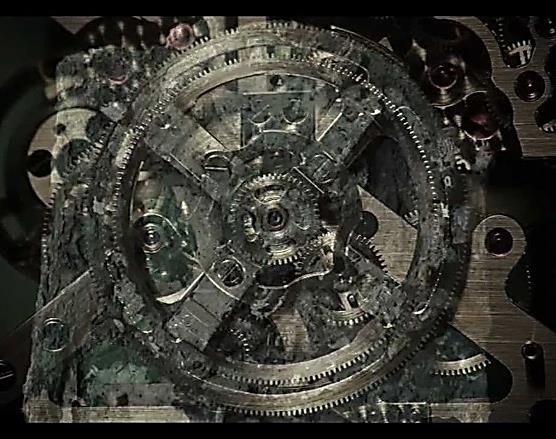

Greek society valued education with a curriculum of arithmetic, sports and music. Science was also taught and the Greeks developed an early form of an analogue astronomical computer discovered in an ancient shipwreck, whose complexity and invention was not matched until the 16th & 18th centuries. The device was used to predict astronomical movements and so provide an accurate reading of the stars as a calendar for religious events, decades in advance. That the earth is a sphere was recognised and its diameter calculated within an accuracy of 5%.

Antikythera Mechanism, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

A world of colour in cities

The ancient Greek world was full of colour, on buildings and sculptures – everywhere. Most sculptures were made in bronze or in clay terracotta and then painted in bright colours, but the colours have long since worn off.

This statue of ‘The Archer’ compares how he looks today, uncoloured with how he could have looked when painted, alive and vibrant. Colour ran throughout the city, foster