Northern Europe – The Netherlands

Outside of Italy and prior to the Renaissance, art was taking very different paths in very different worlds. It was the Dutch who had first taken paintings to a new level with oils on canvas. Trade brought rich customers who wanted bright paintings to hang on their walls and to send home.

At the start of the 15th century the Dutch artist Jan van Eyck had developed painting with linseed oils, building up translucent layers for a ‘glazed’ finish to enhance the colours. Through their trade routes from the Dutch East Indies, they could import bright pigments from as a far away as Baghdad and exotic Persia. Colours were natural, not manufactured and the deep blue of lapis came from Afghanistan. Millions of years ago lapis was thrown up from 35-40 km underground where the extreme heat and pressure had transformed yellow sulphur into a deep ultramarine blue – worth more than gold! Using oils also meant that the Dutch could paint on a ship’s canvas rather than oak board and the canvas could then be rolled up and sent by sea or overland in smaller and faster carts. Paintings became more available and much more exciting. (1)

The Dutch already had established routes for their art as the Netherlands became a centre of trade between the north from England, Russia and Scandinavia and the south with France, Italy and Constantinople (now Istanbul). Bankers provided letters of credit for payment and these wealthy bankers had come from Italy and wanted to send some of this wonderful new art back home. At that time Italian artists were still using an egg-based paint and could not produce the same impression of depth and colour achieved with oils. The bankers spent much of their wealth on portraits, 70 years before the Italian painters such as Michelangelo and Leonardo.

Jan van Eyck was the first to produce realistic portraits that reflected the sitter’s character. He worked for the fabulously wealthy Duke of Burgundy, acting as ambassador and spy with his travels termed ‘secret commissions’. His artistic notoriety and the patronage of the Duke, opened many doors otherwise held closed.

This self-portrait by the artist Jan van Eyck shows him looking challengingly at the viewer with an inscription reading ‘as I Eyck can’. With the exaggerated folds of the bright red ‘turban’ he was showing prospective customers the colour, detail and accuracy of his own work. These true to life portraits were a new skill appreciated by the aristocracy to favourably display themselves and when looking for a wife from another country could see not just her looks, but gave an insight into her character.

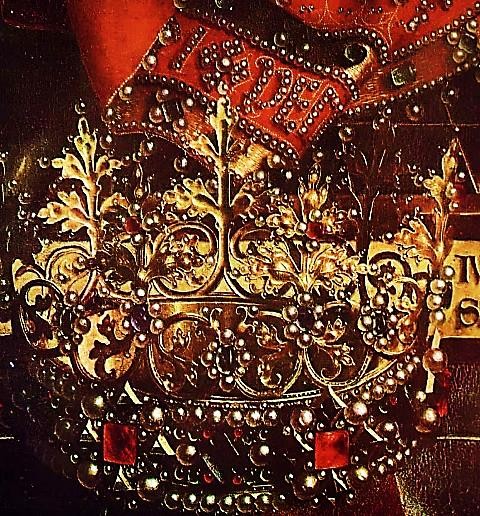

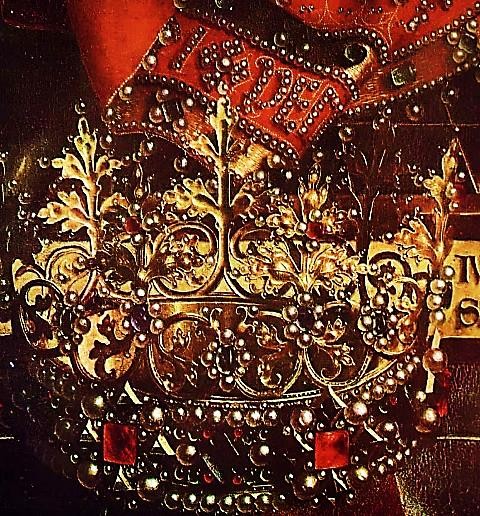

Van Eyck displayed an incredible level of detail, as in these excerpts from his Ghent altarpiece. The detail and richness of colour that he achieved stands out and also shows how he was a master of portraying the brilliance of jewellery.

Self-portrait, Jan van Eyck, 1433 National Gallery, London

The altarpiece was opened on feast days to show rich religious symbols

Ghent Altarpiece, Jan & Hubert van Eyck, 1432, St. Bavo’s, Cathedral, Ghent. (Excerpts are from the top 2nd and centre panels)

Children’s games and town festivals

But as all these bankers, Kings and Dukes lived these privileged lives, what of everybody else, the poor – what were their lives like in Northern Europe in the 16th century?

Well at first with all this trade work was plentiful and the people in the towns lived well. So, they began to have larger families, but with more mouths to feed, the price of their food escalated. Then as the children grew up, there were more people to work and so wages fell, pushing them back into poverty. A life of swings and roundabouts. Their diet was black bread and peas, washed down with lashings of beer, an average of one litre a day each. The water could be too bad to drink, so it had to be beer. But they lived in close communities and celebrations and festivals were their escape from the grind of life, both for children and for adults.

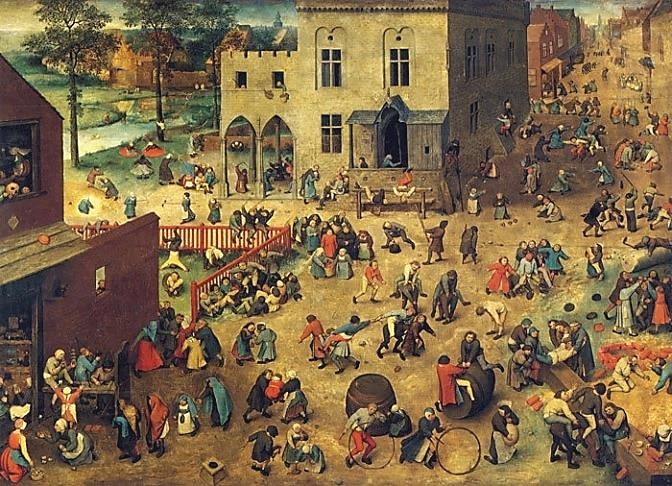

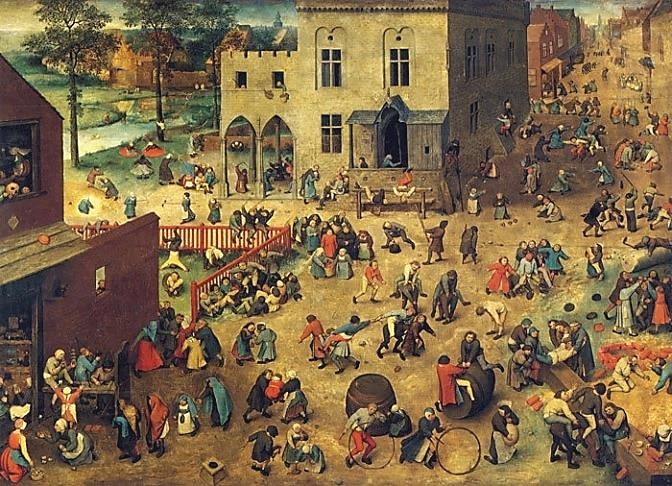

One Dutch artist 130 years after van Eyck, was Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Rather than paint for the rich, he chose to record village life, providing a unique window into a now vanished folk culture and rural society. Bruegel started out in life as a designer of prints, but he moved to Brussels and switched to painting and unusually at that time, depicted peasant life. Bruegel produced many scenes of rural and town life during the 16th century and as his sons and even grandsons were to continue this work, he came to be called Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

His paintings became sought after by wealthy Flemish collectors, who were drawn to the distinct style of dozens of small figures engaged in individual pursuits, seen from a high viewpoint. This was very different to the studied and structured paintings of the day where all was carefully staged in a rigid pose.

Without these paintings we would not have such a vibrant picture of life outside of the cities.

‘Children’s Games’ Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1560, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Amazingly in this painting, from almost 500 years ago, are 80 children’s games.

Playing with dolls, a water gun, an inflated pig’s bladder (like a football), masks, swing, climbing, handstand, somersault, tiddlywinks, marbles, pretend wedding, blind man’s bluff, soap bubbles, riding a broom, ‘hide and seek’, a toy animal, walking on stilts, pole vaulting, leapfrog, rolling a hoop and that’s just 20! These are games still played today.

A town full of children.

There was a poem of the time that ridiculed adults as playing foolish games in their lives like children, when perhaps they should know better, as in the next painting.

This painting has an interesting contrast with an inn (pub) on the left-hand side, with boisterous party goers dancing to a band to celebrate carnival. While on the other side is a church with nuns in black observing prayer and Lent, tending the poor and the sick. One celebrating the church religious festival and the other the carnival party. Each year there was a ‘battle’ between the two sides with competing floats. The fat man on the beer barrel with a pie on his head pushed by a ‘clown’, contrasted by ‘Lady Lent’ on the other, drawn by a nun and a monk.

Town Festival, ‘The Fight Between Carnival and Lent’, Pieter Bruegel the Elder 1559, Vienna

In the middle of the square is the well that serves everyone with water, while at the back of the square are people preparing food and wine. On the left is a scene of joy that food is plentiful and then on the right the religious reminder of the tougher times to come before spring. Both the harvest and the church are important.

The French revolutions

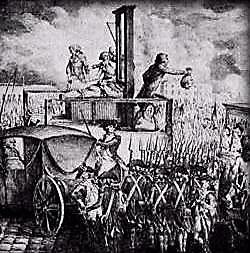

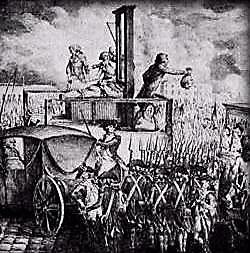

As the 16th and 17th centuries drew to a close, while the Dutch had entered a ‘Golden Age’ (Book 3), in France the poor began to increasingly suffer with grinding poverty and oppression, only worsening through the 18th century. France was bankrupt from supporting the American War of Independence against the hated English, with its people starving from 2 years of drought. The people rose up and the excessive and ridiculed monarchy, together with the crushing aristocrats, were thrown into jail where they promptly came before the Tribunal and people’s judge to be found guilty. They would then immediately be taken to have their heads cut off by the infamous ‘Madame Guillotine’. A dreadful and swift retribution in the ‘Terror’.

Dragged on a cart through the crowded narrow, cobbled streets, overflowing with sewage, they faced crowds of ‘citizens’ crying out for their blood. Terrified and huddled together they would reach the dreaded guillotine and wait to watch those before them being beheaded, before it was their turn to walk up the steps. Between 1793 and 1794, 17,000 would make this terrible journey, to the cheers of the crowd each time the guillotine fell. (2)

Following this revolution, Napoleon became Emperor and took France on a doomed adventure to conquer all of Europe. This was stopped at the battle of Waterloo in 1815, throwing France into disarray and heralding the return of a monarchy. But this new monarchy was itself to become deeply unpopular as they sought to overrule the government and were removed by a second revolution in 1830. France struggled to keep its titular monarchy, but it would finally be removed in 1848 when a Republic was declared with an elected President, in place to this day.

Liberty leading the battle, 1830 Eugene Delacroix, Louvre, Paris

Men and women were equal in this struggle for democracy and women were portrayed as leading men into battle against the aristocrats’ soldiers. Seen here in the second revolution, leading a charge over the bodies of the fallen soldiers. Baring her chest to the enemy she leads and turning with the French flag in one hand and a musket in the other, urges the men on, to raise their tempers for the battle

The painting is a celebration of the victory of the people’s republic to go forward into the future, with a cry of ‘Liberté, egalité and

fraternité’ (‘Liberty, equality and fellowship’) A cry that is still heard in the French national anthem today.

In England they chose another way without terror and blood, but one that still empowered the people.

Romance in England

When Henry Vlll broke away from the church in Rome in 1532, he destroyed all the powerful and rich abbeys and discouraged religious art in the churches. (Book 3) England was now outside of the Italian Renaissance and art tended to be commissioned by the King and the landed gentry in staged portraits, particularly miniatures.

Sculpture was limited to tombs.

It was not until a further 200 years later in the 19th century, that the industrial revolution was to bizarrely develop an art for the ordinary people and then in romantic paintings. A contradiction, but also a progress.

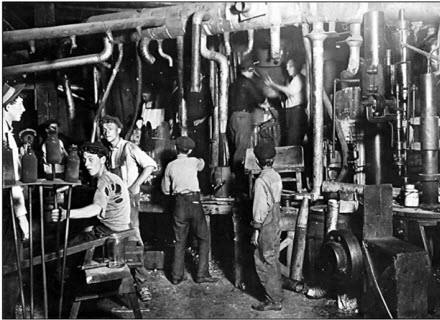

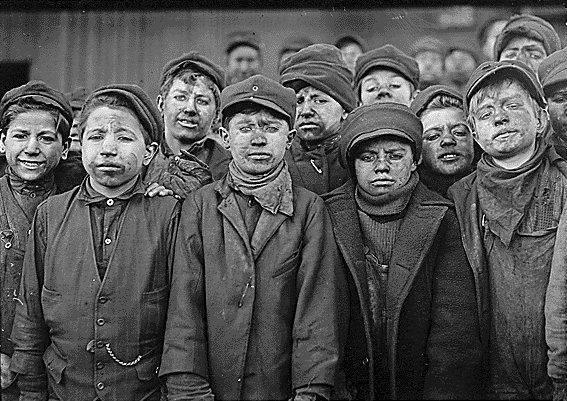

In the Victorian age; 1837-1901; living conditions in the new industrialised towns were terrible, with dreadful housing in slums and dangerous working conditions. These brought poverty, poor health, hunger, high child mortality and minimal education. In these living conditions people will despair and foster a dangerous resentment. Later photos came to record the people and their conditions.

Whitechapel, London, 1880’s

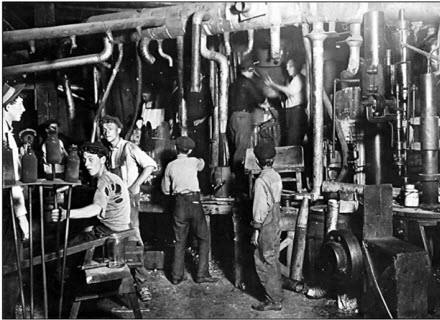

Glass factory 1908

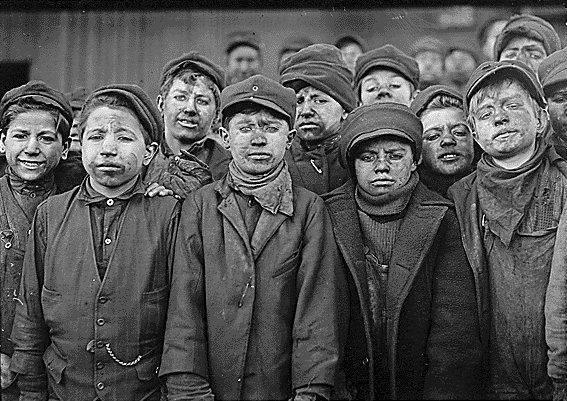

They portrayed the ignorant poor children who had their lives taken away from them, with no hope for the future. This suffering has been immortalised in the hymn ‘Jerusalem’, as ‘those dark satanic mills’.

Coal mining 1911

Mill workers 1910

This was a recipe ripe for revolution as happened in France and one that the British government sought to avoid. They introduced a succession of reforms giving people the right to vote (although women had to wait another 50 years), with worker’s trade unions. Public health improved with clean water through sewage removal and education was compulsory for all children. Children as young as 5 or 6 had worked 10-15 hours a day, often barefoot with no shoes, in dreadful factories and mines. This first reform only changed to a minimum age of 9 years old and working 12 hours a day. (3)

As the reforms were enacted, public bodies sought to engender a pride and ownership in their towns, with grand public buildings, as in ancient Athens. (Book 1) A national pride grew as the British Empire strode the world and ‘Great Britain’ under Queen Victoria, stamped its place in the world and in people’s lives.

Victorian Leeds Town Hall,