The ‘...Isms’ of Art

Modern Art for a Modern World

The 20th century heralded new industrialised societies with a new middle class defining the new world for themselves, such as the adoption of impressionism against the upper-class art ‘establishment’. (Book 4)

Artists were seen as the bohemian voice of society and free to express extreme opinions. Their art not only challenged traditional forms of art, but some saw themselves as a protest movement against bourgeois interests and the cultural values that shaped society, which they believed led to the First World War of 1914-18.

This was a time of great change as the war shook societies throughout Europe with 15-19 million deaths and 23 million wounded military personnel. It was the people who suffered and who termed it as ‘the war to end all wars’. The great empires of Russia and Austria fell and everywhere democracy was established as the people vowed never again to be taken to war by their rulers. But as we shall see, it would happen again.

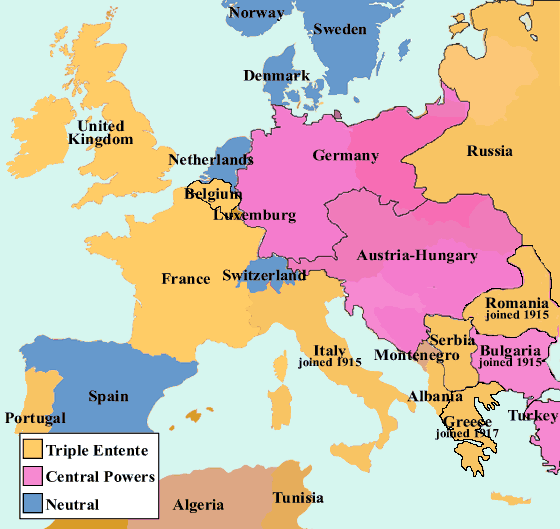

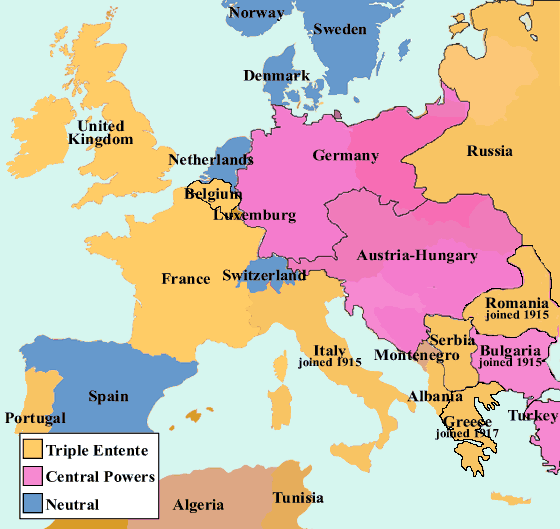

The First World War had been triggered by the assassination of the Emperor of the fading Austro-Hungarian Empire, by a Bosnian-Serb nationalist. The Empire decided that retribution must be made and set out to invade Serbia, who were Russia’s friends and who in turn declared war on the Empire. Germany rushed to the Empire’s defence declaring war on Russia. France had agreed to support Russia and so joined in. Germany then moved against France through Belgium, who Britain had agreed to support and so Britain joined in, creating a Russian, French and British axis, or ‘entente’. War now covered Europe to the bewilderment of the people, who were suddenly told that friends were now enemies. (1)

Europe in the First World War

Mistrust between nations and a breakdown in diplomacy were to reap a dreadful cost on the men called to the fight, in a supposed defence of their nation. Nationalism was to pay a terrible price.

The 20th century had already brought great changes in society and the turmoil of war was to bring extreme changes in Art.

Following the art of Impressionism of the 1870’s and 1880’s, (an early ‘ism’), the door had been opened for artists to experiment and a rush of new forms and styles defied categorisation as artists shared ideas. With a new society embracing change, anything was possible and in art all possibilities were explored. Reviewing these early 20th century developments can be confusing and much like a mad tree branching off in all directions. But if we follow the journey made by the artists rather than the categories imposed by art critics with their ‘isms’, a clearer picture emerges.

These artistic movements all had one thing in common of looking to the future and stepping away from the past.

Four Artists and Futurism

In 1909 a challenging article by four Italian artists, was published in Italy and France stating ‘We want no part of the past …. we the young and strong Futurists’. They disparaged anything old and traditional for the new world of speed and technology – the car, the airplane, industrialised society and they were passionate nationalists. They praised originality ‘however daring, however violent’. So as fervent nationalists, they were as much a sociological as an artistic movement, expressing dynamism and energy in an age of new scientific developments. (2)

This vision brought four artists together looking for a ‘universal dynamism’ in art with a style to break-up and then brought these separate objects together, to be followed by the cubism practised by Picasso. They perceived a world in constant movement. Rushing cars, trains, planes and bikes were featured and even found their way into advertising.

Movement was everything

‘Futuristic Motorcycle’, Fortunato Depero, 1914

‘Unique forms of Continuity in Space’, Boccioni, 1913

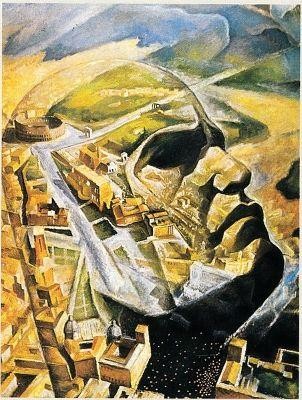

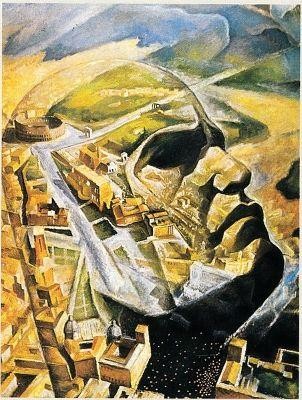

With its focus on nationalism, inevitably the Futurist movement was brought into politics and in 1914 they campaigned heavily against the then all-encompassing Austro-Hungarian Empire, heralding Italy’s entry into the First World War in 1915. The realities of war were to bring the group into disrepute and they began to break up. But in the aftermath of the war, Fascism became the hope of modernising Italy with its industrialised North and archaic South. (‘Fascism’, defined as a far right, authoritarian, ultranationalist, dictatorial society) The futurist style was taken up by the new fascist regime under Mussolini and came to express the new modernist and nationalist vision, leading Italy to join fascist Germany in the next world war.

With Mussolini’s guiding figure

‘Women, Stairs, Skyscrapers’, Fortunato Depero, 1930

‘Mussolini Aviatore’, Gauro Ambrosi, 1938

However, as Italy’s fortunes later suffered during World War 2, so the vision of a new powerful, all conquering society fell away, and Futurism was consigned to a past that it had earlier rejected.

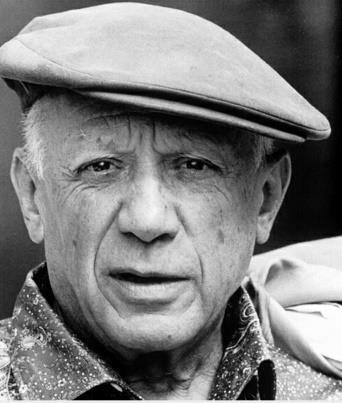

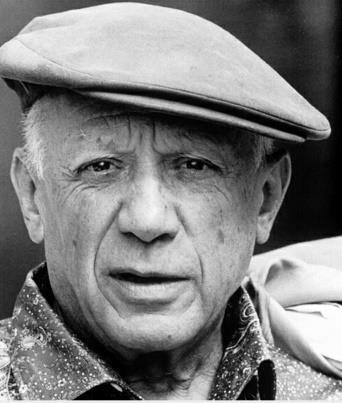

Throughout this time a giant of 20th Century Art – Pablo Ruiz Picasso, 1881-1973 – was developing his style of ‘cubism’, building on the concept practised by Futurists, that was to echo around the world.

Pablo Picasso & Cubism

1908 aged 27 and 1962 aged 81

1908 aged 27 and 1962 aged 81

Prominent amongst this ‘new wave’ of art was Pablo Picasso. With an extraordinary talent, his mother recalls his first words as ‘piz, piz’ – ‘pencil, pencil’. His father was an established traditional painter and lecturing art professor and gave his son a formal academic art training. He very soon recognised that his son’s skill had surpassed him and enrolled Picasso into a School of Fine Arts. But Picasso lacked discipline, skipping classes and instead immersing himself in works such as those by El Greco from the Renaissance with elongated limbs, startling colours and mystical backgrounds. (3) Picasso was developing his own view of ‘modernism’ and in 1900 aged just 19 he made his first trip to Paris, then the art capital of Europe and which became his home for the next 60 years. With no income he lived in extreme poverty and cold, often burning his paintings for warmth, sleeping during the day and working by night. Picasso’s work had a hard beginning.

His work tended to a gaunt, modernist style and he went through periods where he favoured the colour blue and then rose. Picasso always portrayed a sombre mood, reflecting how earlier he had been traumatised by the death of his sister aged 7 and now by the suicide of a close friend. But his fame was spreading, even to New York where the famous Stein art collectors sought his work. But what route was his work to take?

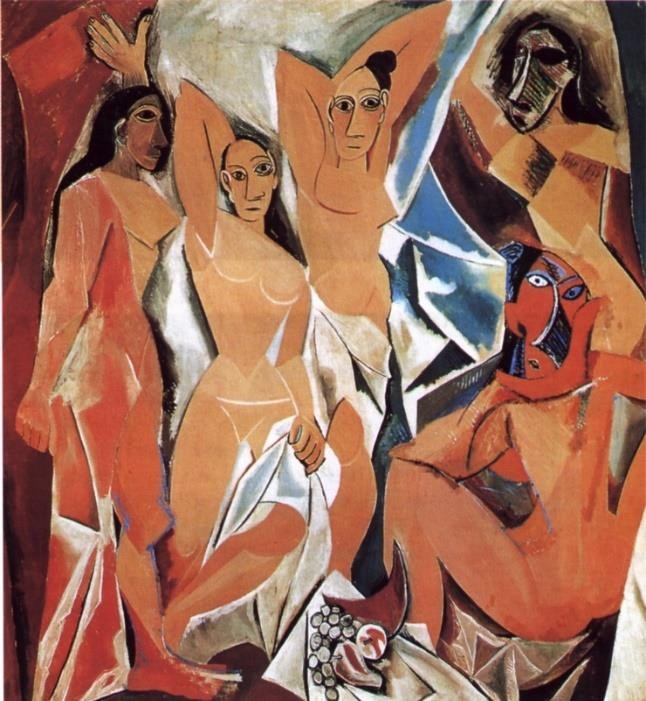

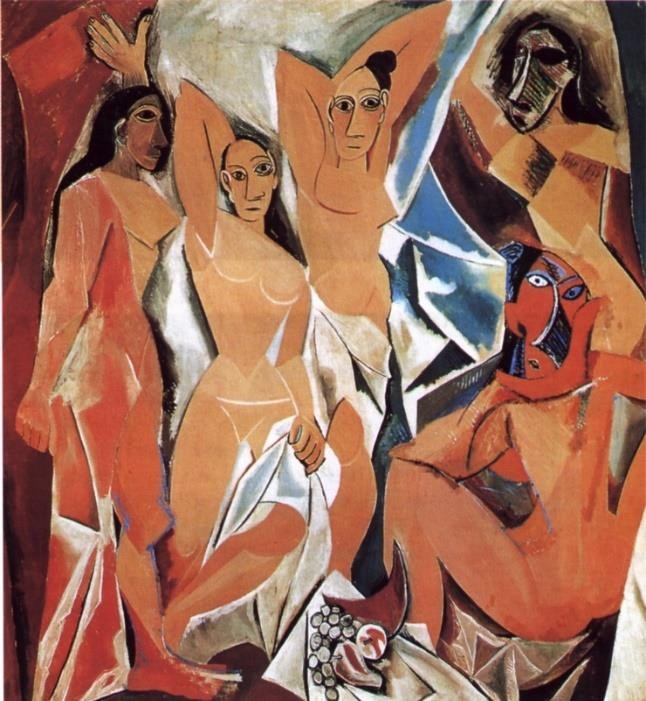

In 1907 he visited an exhibition of African artefacts and was impressed by the long- faced masks, which he then copied and introduced into his painting of prostitutes: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the birth of Cubism.

19th century, traditional African ‘Fang’ mask

The poor occupied his mind and prostitutes and beggars became much of his subject matter. His first cubist work was of these prostitutes, leading to the work being described as ‘immoral’. This caused Picasso some doubt and he did not show the painting until 1916, nine years later. In this interval he may have worked on the two heads on the right, which are clearly distinct from the other faces and reflect the African influence.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Pablo Picasso, 1907

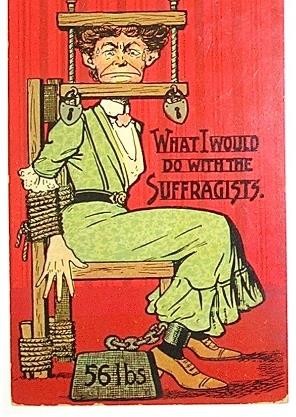

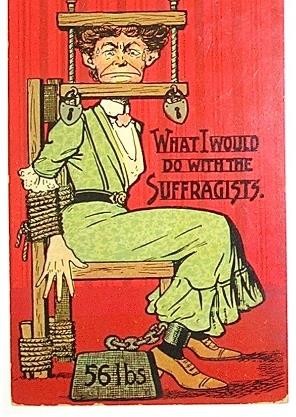

Picasso’s concern for the lives of women reflected a time when women were campaigning for the vote and greater equality with men. Suffragette (women’s right to vote) protests caused division in society, challenging society’s status quo. Women were arrested, jailed and derided in the popular press. But across the world women came to gain the vote, with society enacting further change in the cries for equality. The world had changed since the 19th century.

In the meantime, he worked with another artist Georges Braque and together they developed a cubist style that took apart objects and reassembled them in a stylised abstracted form, highlighting their shapes in multiple perspectives, as practised by the early ’Futurists’. (4)

Girl with a Mandolin, Picasso, 1910

Georges Braque, Little Harbour in Normandy, 1909

The Reservoir, Pablo Picasso, 1909

In the face of criticism, the artists showed their works at the Salon des Independants in Paris, as had the Impressionists before them. Like the Impressionists they had a patron in an art dealer, Daniel-Henry Khanweiler, who guaranteed them an annual income for the exclusive rights to their paintings. The history of modern art may have been very different without these patrons and the doors that they opened.

Around 1920 cubism became less popular, but Picasso was not interested in which school his work could be designated, but only on the effect.

His work became more elaborate and one recurrent theme was ‘The Weeping Woman’. Picasso explained ‘For years I’ve painted her in tortu