Lost and reborn in Italy

Greece copied Egypt, Rome copied Greece and Italy copied their forefathers in Rome, calling it a ‘Re-naissance’ (re-birth) But all had very different societies and Medieval Italy was entirely new.

The culture and art of the Greek and Roman empires were to be lost for a thousand years, but were to be rediscovered in the renaissance in Italy. A dramatic and sustained increase in population across Europe with increased food, health and life expectancy, that all combined to drive a dramatic increase in trade. Newly rich merchants and bankers fuelled a demand for art. The art patrons had arrived.

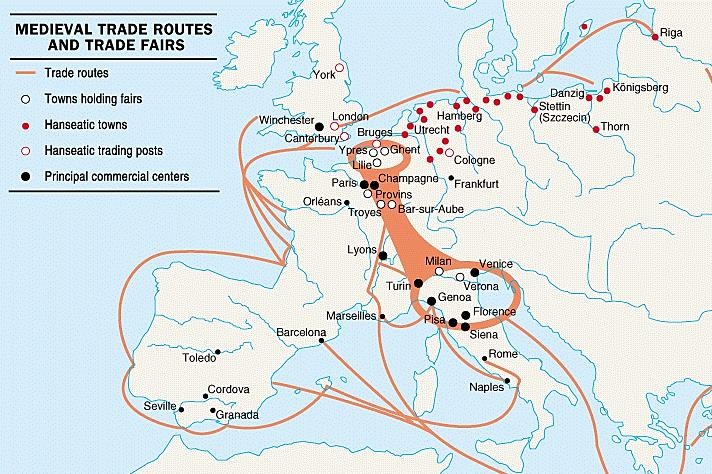

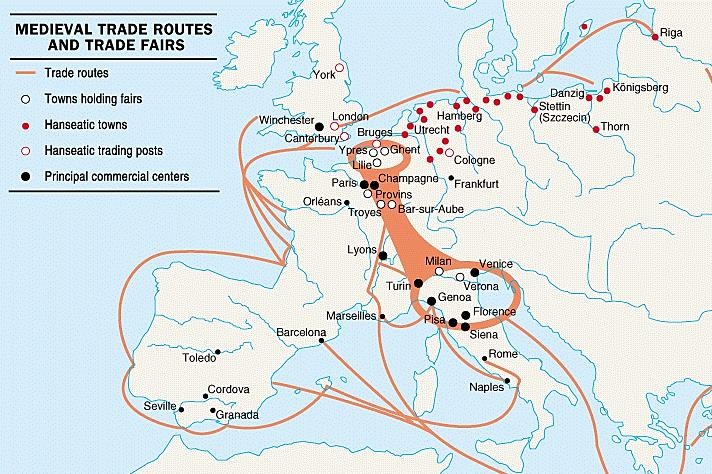

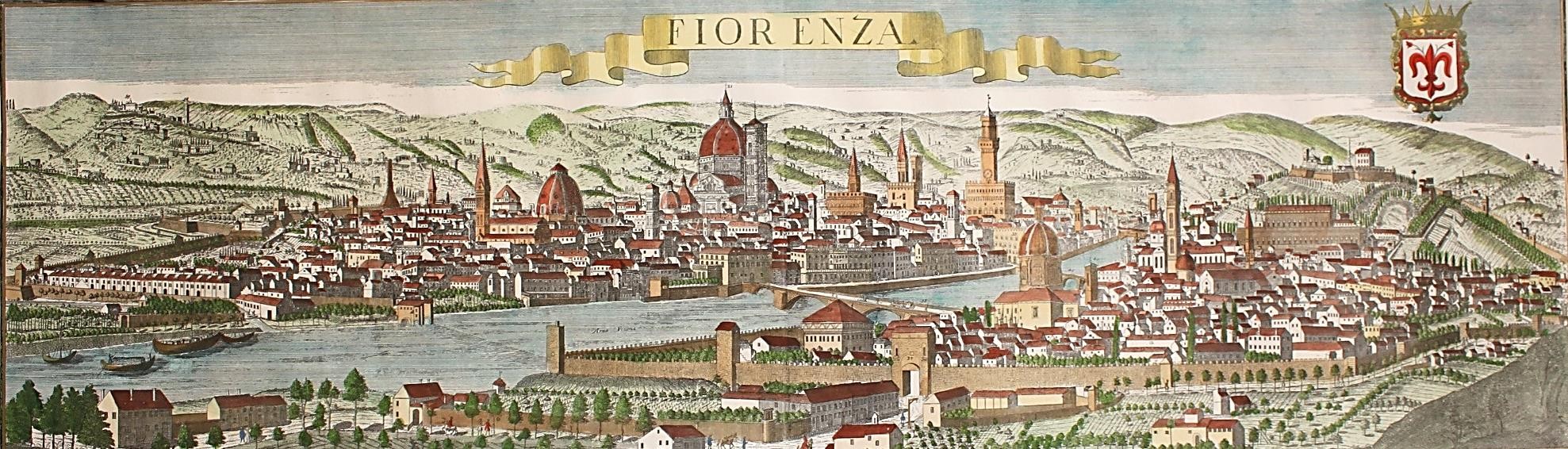

So by the 14th century, 900 years after the fall of Rome, trade had recovered and again flowed through the states of Italy. From Venice and Florence and then on to France, the Netherlands and England, even on to the Baltic. (1)

A rich circle of trade financed by powerful bankers that grew to develop commercial contracts. These wealthy families sought a status through the perceived sophistication of art and soon their art patronage eclipsed that of the Church or Aristocracy. Art moved from the Church to the people.

Their wishes came to influence the nature of art.

Rich merchants and even richer bankers brought wealth to the cities and their new villas began to replace the old dark wooden houses. But, at night the cities were left in darkness by the lack of streetlights, with just a few very dim oil lamps in the major areas. The narrow side streets stayed completely dark and black, where you would need to carry a flaming torch to light your way home.

Gradually the money from trade by the rich began to filter down to the lives of the poor and cities prospered. In Florence, even a peasant maid’s family would expect to offer money to persuade another family’s son to marry their daughter. It was more of an arrangement between families than an act of love, with lavish weddings. (2) Wives were expected to raise young boys to grow up to be healthy, educated young men and so more families could become successful and wealthy. An educated middle class was born.

Their children went to schools to study Mathematics, Greek and Latin, the ancient sculptures and classical literature where art was valued in a virtuous life.

Realism in art was reborn, away from the religious taboos where the ban on ‘graven images’ resulted in a cult of flat, un-natural images. This new art raised peoples’ aspirations and citizens rejoiced in this new culture, in which banking families were the leaders. The great cities of old were returning with a civic pride.

But it had taken a thousand years for these great cities to grow again, with their ancient art re-discovered (the ‘re-birth’, or as termed in French as the ‘re-naissance’). This new style was expressed as ‘humanism’ in a philosophy adopted across Europe to engage all citizens in an ethical, harmonious civic life and in its culture.

By the 15th century the ancient civilisations and art of the Greeks and Romans, had become to be admired and artists again went to schools of ancient art to study the beauty and realism of these works. Across Europe the church, aristocracy and the new wealthy merchants and bankers competed to be part of this ‘humanist’ sophistication. A sophisticated culture grew that is still admired today.

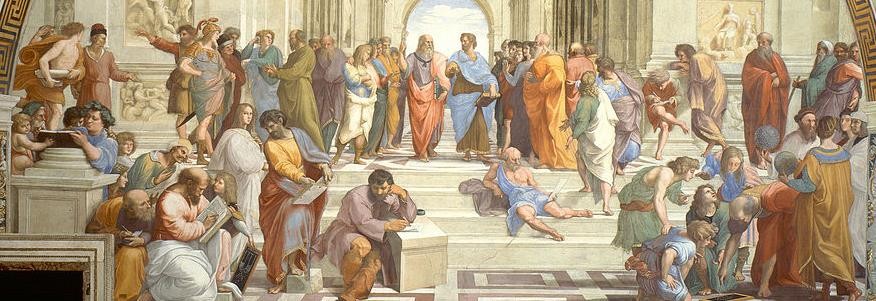

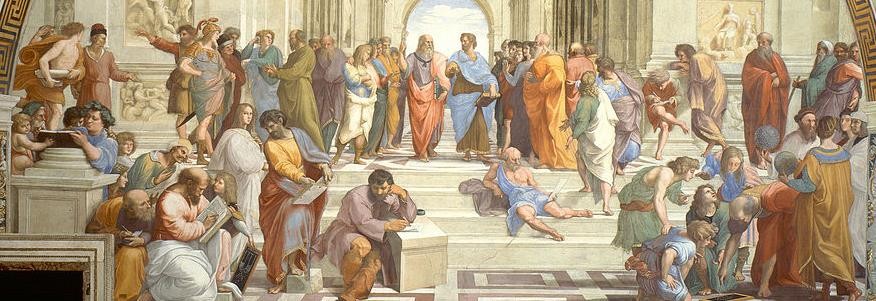

Seeing themselves as part of a new sophisticated social class, these wealthy patrons would go on to commission the best artists who could produce an art of beauty - true to life. The ancient Roman sculptures that still remained in Italy, provided examples and inspiration for the artists to sculpt with realism and balance. Great artists such as Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and Donatello came to fame. This fresco by Raphael depicting Ancient Athens, symbolises the marriage of philosophy, art and science drawn from Ancient Greece, with the science of Leonardo. Plato and Aristotle are dominant in the centre, whilst Raphael depicts himself lounging on the steps with Michelangelo at the foot, struggling to achieve perfection. The ancient philosophers and their values became the hallmark of the Italian Renaissance.

School of Athens, 1509-1511 Raphael, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City

Artists designed buildings, created beautiful sculptures and painted great art. They were to transform cities and bring art back into ordinary people’s lives, providing a unifying culture on which to build a cohesive society.

But it was the patrons looking to secure their status in society and establish their sophistication across their European markets, who would fuel demand and determine the nature and style of the art.

You only have to look at one religious sculpture to see how realism was again embraced, even in churches. This sculpture from 1463 depicts the friends of Jesus rushing to him when they heard of his death.

With their head-dress and cloaks flying and crying out in dramatic style, it was too detailed to be carved in marble and was instead modelled in clay and baked as terracotta (‘baked clay’). It was then painted in vivid colours, that have now long since faded away.

Sculpture was transformed into something lifelike, dramatic and exciting. These women are life size and seen rushing to find Jesus dead. The excitement of the age has even caused the church to change.

This realism is in contrast to previous religious dogma and teachings and brought religion directly into people’s lives rather than previous portrayals of a heaven far away from this world.

Lamentation, Nicollo Dell’Arca, 1435-1440, Bologna

But, as we shall see, there was fierce competition between the independent states of Italy fuelled by the rich trade of powerful bankers and merchants, where power and control were everything.

Retelling history through art

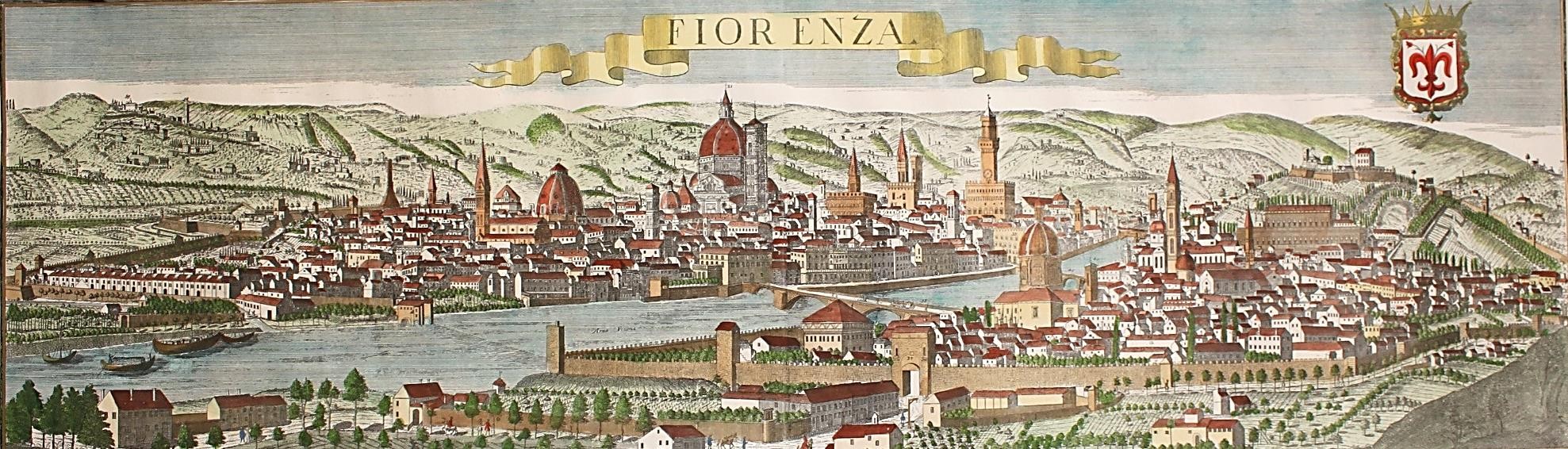

Florence had become the richest state and so had the biggest army to wage a string of wars between states. In this bustling 15th century, the Medici banking family had used their great wealth to gain control of Florence.

The Medici’s family’s wealth came both from trade and from managing Church money across Europe. (11)

View of ancient Florence, by Probst

The rich could now afford to have art made that reflected their power and status and so their version of history. They wanted to show the world the superiority of Florence across the region and display their fine tastes. They aspired to be recognised as the wisest and most cultured across Europe and so they sent out for the best artists to make the best works of art. These were to emulate the grace and realism of Ancient Greece which was now the standard throughout the European aristocracy. As they competed amongst themselves to be the best and the most cultured, they often ordered different versions of the same subject, to suit their personal standing.

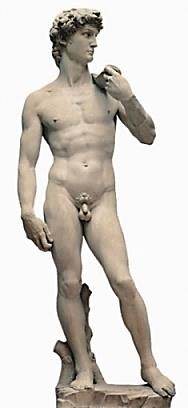

An example is in the varied statues of ‘David’.

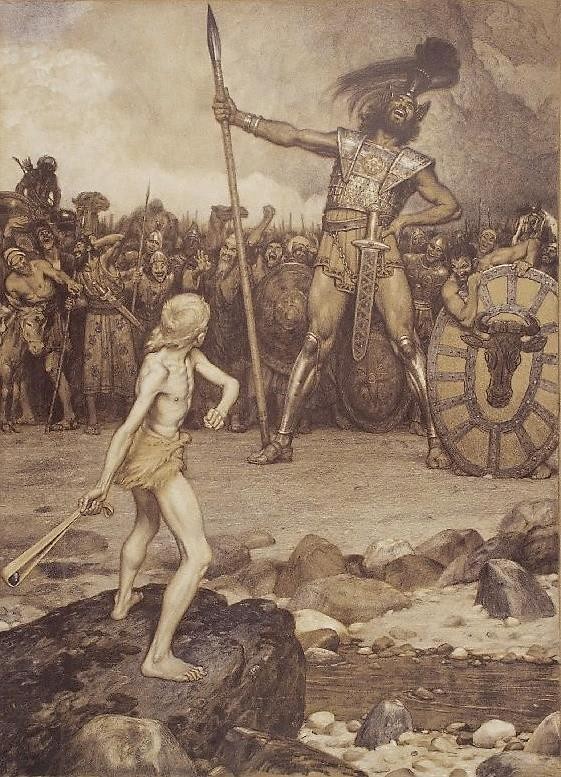

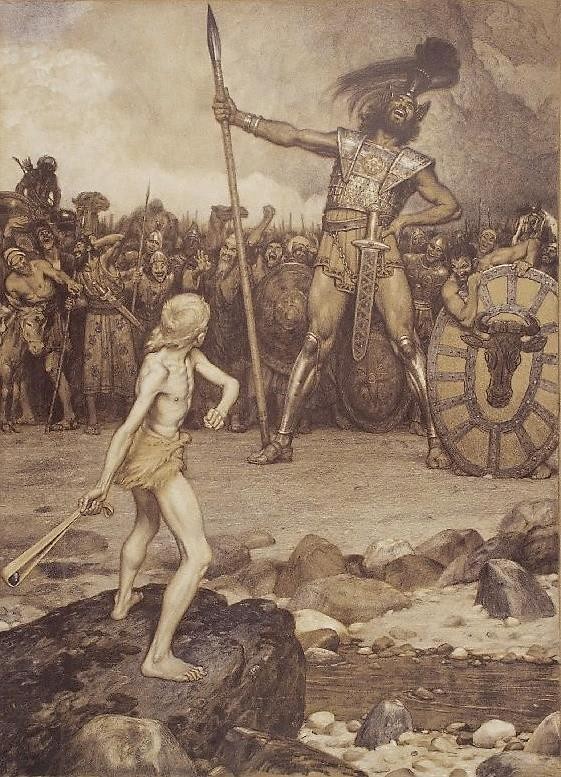

Sculptures often celebrated great events from the past and the battle between David and Goliath was one that celebrated the power of good over evil. The battle had taken place some 2000 years earlier, but the story was well known as it had been celebrated in the Bible and so read out in church. Celebrating how the Israelites (Jews) defeated their enemy, the invading Philistines, the legend demonstrates how the ‘few’ can defeat the ‘many’. This was very relevant to the many Jewish bankers who were a minority in Italian society.

A shepherd boy David went out armed with just a sling to meet the Philistine champion Goliath, who had challenged the Israelites to settle the war by single combat. Goliath was a giant, carrying a huge sword and spear and towering over David. The mighty threaten the small.

Picking up some stones David walked bravely forward, throwing down his armour. The Philistines laughed and then, as both armies looked on hushed, David spun his sling above his head and before Goliath could use his mighty sword, launched his stone. He struck Goliath in the middle of his forehead and he crashed to the ground, dead. David cut off the dead giant’s head and held it aloft. Seeing their leader killed so easily, the Philistines fled the battlefield and Israel was saved.

Courage and right were rewarded.

The Renaissance philosophy praised individual values of honour and glory in this life, rather than being merely a gateway to an afterlife.

Antique print, 1900, Schindler

But the character of David was open to interpretation.

The church in Italy dominated people’s lives and the rich wanted to secure their place in heaven. This story of the triumph of good over evil was known by everyone and artists were paid by rich merchants to celebrate this biblical victory and so secure their place in heaven. As a result, there is more than one sculpture of David and each one was ordered by a different patron and made by a different artist and each shows a different story that each wanted to portray. Patrons were deciding the nature of art.

The first was by ordered by the banker Medici who controlled Florence, to show his perfect taste.

He sought the best sculptor of the time, Donatello who portrays a young and slim life size portrayal of David, victorious after the battle. This delicate style was very different from other sculptures of the time. David looks down at the head of Goliath that lays at his feet and prods it with Goliath’s sword. The message was that the Medici family were always victorious and were the leaders in style and society, not just cold mercenary bankers. The sculpture was made in bronze and could be polished to shine with the beauty of David. This life-size work stood in the courtyard of the banker’s house for all their guests from across Europe to admire and so admire the Medici. Daring to be the first nude sculpture in Florence and clearly effeminate, they invited controversy, further demonstrating their unchallenged position in society.

‘David’ by Donatello – 1440

Museo Nazionale, Florence

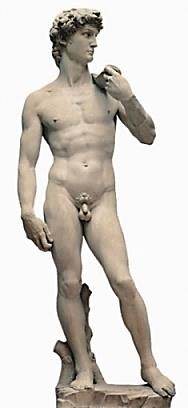

And then later there is Michelangelo’s idea of a proud, but tense David before the battle and is the most famous. The first huge nude since antiquity, this was a daring sculpture on which he laboured for 4 years.

Cut from a single block of marble that had lain neglected for 40 years as other sculptors were put off by flaws inside the block, Michelangelo worked secretly day and night inside a black tent. This huge sculpture stands 17 feet high, a tremendous three times the size of other life size sculptures. It was made to sit on the top of the roof of the Duomo, Florence’s cathedral.

As a result, when you look at the sculpture from ground level, David’s head seems bigger than you’d expect. But when you look up at the sculpture from underneath; as you would have done if it was on the roof; then it all looks in proportion. It had to be big to be seen from the street below. But, then no one could lift this huge 6 ton sculpture up on to the roof and so instead it stood in a public square outside the governors’ offices, who had commissioned the statue. Ironically this was closer for the people to admire and all the better to announce to the states all around Florence that the hero David was a symbol of the peoples’ strength and would protect and overcome all enemies.

Completed in 1504, it was not until 1873 that it was moved inside a gallery.

‘David’ by Michelangelo – 1504, Galleria Dell’ Academia, Florence

Next came a sculpture by Bernini who was aged just 24. (see later)

Again, life size and shows David in the moment of launching the stone. David had thrown aside his armour as he advanced on Goliath and it lay at his feet. This marble sculpture does not have the grace and beauty of the earlier bronze work, but is all power and action as it steps out into the viewer with a strong, determined look. This powerful image was ordered by a church Cardinal for his villa and stood as a statement of his power.

‘David’ by Bernini – 1624 Galleria Borghese, Rome

Three sculptures portraying David before, during and after the battle for three different patrons who each chose their own version of the ‘reality’ of that event and of that person. It was the rich merchants or the church who decided what people see and believe. Even history can be influenced to present a particular version. As Winston Churchill said: ‘History is written by the victors’.

Even today we see individual and corporate wealth determining architecture in our cities and founding new art galleries that compete with an art designed primarily to attract visitors and so enhance their status in society.

With the demand for their work, Renaissance artists thrived, also receiving commissions in architecture with grand buildings. Art began to again dominate cities as in the Greek and Roman world of old.

The great Italian artists – Leonardo da Vinci

This same revolution of a renaissance in realism and expression that was seen in sculpture, was also expressed in paintings, although they still portrayed perfect and ideal figures. Where previous paintings had looked ‘flat’, now they had depth – perspective – giving the illusion that you are looking into a real scene. This was coupled with a burst of wonderful colour in paintings on church walls and then on canvas. As Popes, Kings, Emperors, Dukes and the new rich merchants and bankers competed for the best, art was raised to new levels and artists became revered for their skill. The Medici family who commissioned the sculpture of David, now had a banking business that extended from Italy up to the north at Bruges, in the Netherlands. Bruges was the leading centre for the wool trade and so became a major trading city as well as an art centre for Northern Europe. The Medici had a long and powerful reach across European countries and so influenced tastes across varied societies.

While the Italian states fought between themselves both in battle and in trade, they were also rivals to be the most cultured and so were also in competition for the best artists. As art became exclusive to the richest and the most powerful, art became political in a projection of ‘soft power’ to assert their position. But this also brought beauty and pride to the cities and unified societies emerged, creating stability and bringing business and increased wealth. Other new artists seized these opportunities and more works became more freely available.

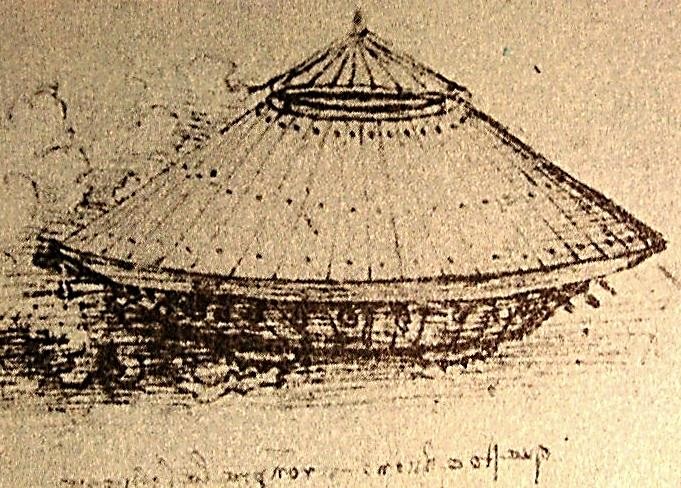

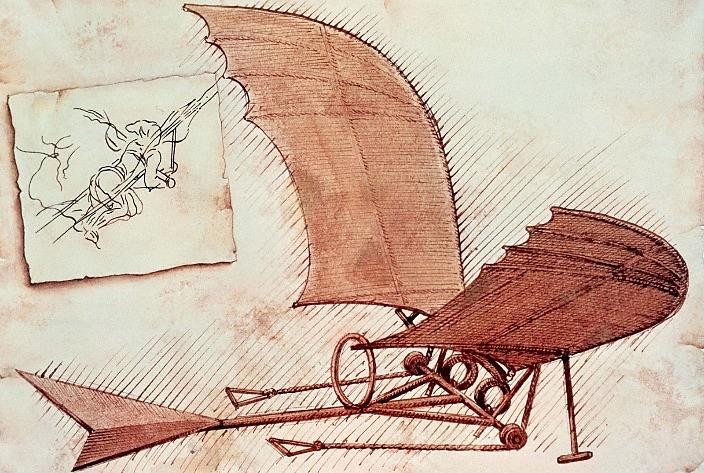

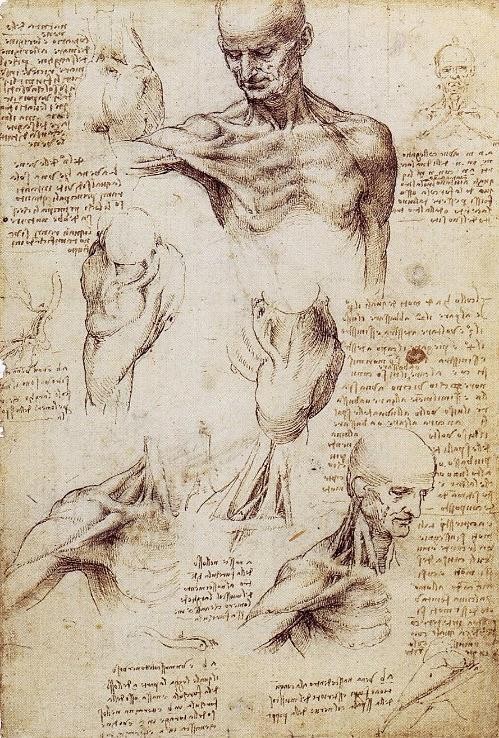

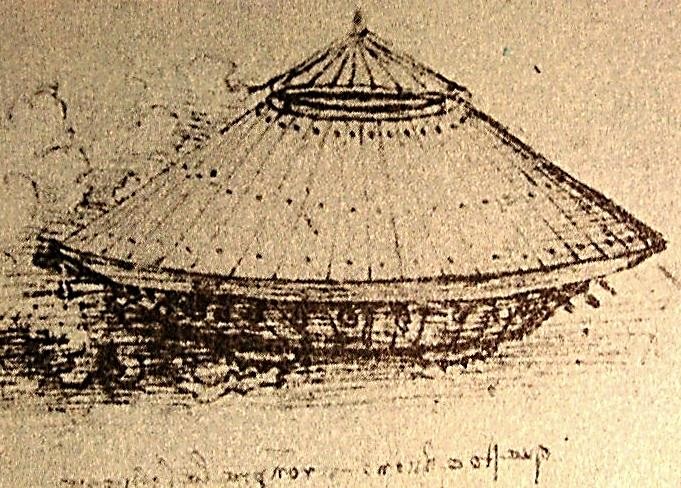

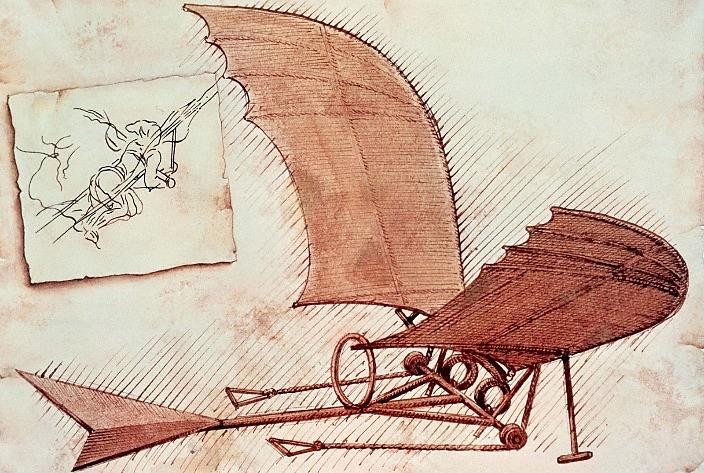

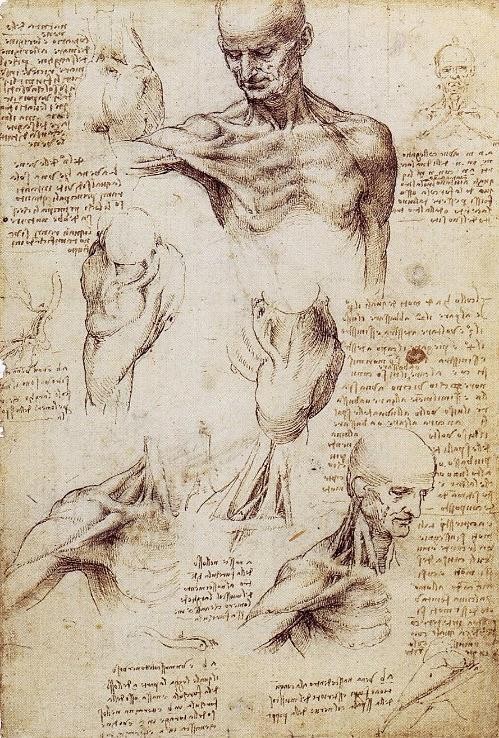

One of the most gifted of these artists was Leonardo da Vinci who became an apprentice to the famous painter Verrocchio. Although entirely self-taught, his early work so impressed that it is said that Verrocchio never painted again. Leonardo not only produced great art, but complemented this with the science of the Renaissance, designing military weapons for the wars. He drew the first flying machines, engineered canals to divert rivers, even wrote music. This range of talents made him attractive to the rich and powerful. The Duke of Milan realised this when Leonardo worked for him from 1482 to 1499. ‘Worked’ is debatable as in those 17 years Leonardo was so pre-occupied with his ideas, that he produced just 9 paintings and not all for the Duke. It seems that Leonardo preferred the process of concept and invention, rather than the finished work. (4)

He invented armoured fighting machines (tanks), canons and catapults to breach city walls and barricades to protect them. He designed double hulls to protect ships and even flying machines to hold a man.

But most were never to be built as the technology to build them had not kept up with his ideas, which were way ahead of his time. The Duke of Milan would have relished these advances as his family fought wars with an advancing Venice and then under siege from France, only to be rescued by the Habsburg Empire. (Book 3)

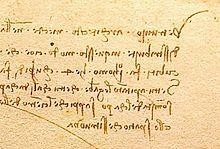

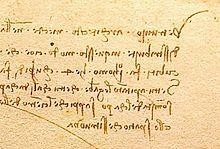

Leonardo was so keen to keep his inventions secret that he wrote in a mirror image, so to read his writings you had to look at the words in a mirror.

Although Leonardo considered himself a creative visionary and inventor, his studies of the workings of human and animal bodies meant that his art was true to life.

The description ‘genius’ can well be applied to Leonardo. He had so many ideas that a collection of 30,000 pages of his notes can be seen today in a chateau in Amboise in France. On the invitation of Francis 1 he had retired there for 3 years before he died aged 67 in 1519. His creativity can be seen in his famous, but few artistic works, which show us his true genius in capturing the character of the sitter. Being so innovative, he was among the first Italians to use the Dutch invention of painting with oils on canvas, allowing more vibrant colours.

As Leonardo was known for the use of vibrant colours - even in his own clothes - the Parisian Mona Lisa now cracked and yellow with age, may not be a true depiction of his work. A copy in Madrid made by an apprentice of Leonardo, may show a different view. This was very possibly made in the studio at the same time, but not subjected to the heavy varnishing used in later restorations. Similarly, his depiction of The Last Supper is even more degraded, but again an apprentice copy shows the true colours. (5) We can see this colour in another earlier work by Leonardo, Lady with an Ermine