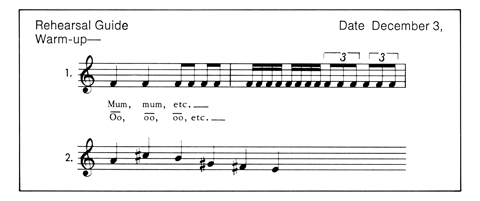

A rehearsal guide, such as shown in figure 1, can be used to establish balanced, consistent rehearsals. This kind of attention to planning will pay off for both the director and the choir. The director will find that the use of a rehearsal guide will discipline his approach to each rehearsal.

Sing the first four notes on an "oh" vowel, not fast. Add the last two notes and move the tempo up gradually.

Secondary purpose of warm-up

Strive for clarity of notes. (The theme [No. 2 of figure 1] is that used in Britten's Wolcum Yole!, Boosey and Hawkes.)

1st Selection

Wolcum Yole!—work to clean up the moving notes at both the text, "Wolcum Yole!" and "Be thou heavne King" passages. Apply the principle of diaphragmatic support, (used in warm-up) to the moving notes. Work to the soft section.

2nd Selection

"Break Forth, O Beauteous Heavenly Light," J. S. Bach, G. Schirmer.

Stress the amount of room needed to produce a free tone. Then use text, still striving for room in the mouth. Have students place index finger in front of the ear to detect jaw motion.

Continue to use text, emphasizing the growth principle, striving for the continued deepness of the tone, open throats, and growth in the tone.

3rd Selection

"Now Thank We All Our God," J. Pachelbel, Robert King Music Co.

Begin on the last section, sing on pum; stress the rhythmic activity and its relation to the cantus firmus. Use C. F. with text, other parts on "pum". Emphasize the relationship between the C. F. and the other parts, including dynamic levels needed to achieve clarity of both.

4th Selection

"Psallite," M. Praetorius, Bourne Music Co.

This is an easy piece that that the choir can perform rather well quite quickly. Work for balance, blend, and style. Must not be too forceful, although rhythmic. Work for correct word stress. Be careful of Latin and German pronunciation. Have choir speak text.

If Time

Repeat Wolcum Yole!, recapping work done at beginning of rehearsal. If possible, continue to end of work.

If there is a chalkboard available directly in front of the choir, list the pieces that will be rehearsed in their rehearsal order. As the singers are seated, they can begin to place the music in order, saving time later in the rehearsal. Rehearsal time will be conserved if the choir has permanently assigned music folders. Except in an emergency, rehearsal time should not be used to distribute music.

After the pieces have been selected for rehearsal, the following points will aid in determining the order in which they will be rehearsed.

1. Place the most difficult task of the rehearsal toward the beginning of the rehearsal. Either begin with it or precede it by a short work or only a small portion of a work, so the singers will be fresh for the most difficult work of the hour.

2. Do not rehearse passages in extreme ranges before the voices are properly warmed up.

3. Try to put different styles into the rehearsal, but do not mix the styles so much that there is no continuity and no carry over of ideas.

4. When possible, use two or more works that have similar problems.

5. Do not rehearse several pieces in a row that have a high tessitura or whose total vocal requirements are quite demanding. If this is done, the rehearsal will really be finished long before the director dismisses the students. If the singers have to sing too long in extreme tessituras they will quickly tire and be unable to respond to normal rehearsal demands. The tone quality will also suffer and the singers will begin to force to try to regain the lost quality. There is only one result; a poor rehearsal.

6. Separate the most difficult pieces with easier ones. Do not devote an entire rehearsal to just difficult repertoire. The singers' mental and vocal abilities will be overtaxed and much less will be accomplished than desired.

7. Build variety into the rehearsal even if it is variety within only several works (choosing contrasting sections, etc.).

8. Do not always start at the beginning of every piece. Beginnings of pieces are often over-rehearsed to the detriment of the rest of the work. Do not waste rehearsal time singing through sections that the singers know. Go immediately to the place in question. It is often worthwhile to begin rehearsals in the middle of a work.

9. It is also desirable to have the choir sing one piece in its entirety or a section of a longer work during the rehearsal. It should be remembered that they will not always share your enthusiasm for part learning.

10. Place a short break in the middle of a one-hour rehearsal. Confine the members' talking to a few moments during the break before the necessary announcements (place announcements at the break rather than at the beginning of the rehearsal).