In 1172, an Augsburg priest named Wernher wrote, “A poem I begin / in love of holy Mary” [Eines liedes ich beginne / in sente Marien minne” ll. 1-2]. These are the opening lines of his Maria or Driu liet von der maget (three poems about the maiden), composed in Middle High German verse. Wernher’s roughly six thousand lines have the distinction of being the earliest vernacular life of this figure so central to Christianity throughout its history.[] Apparently motivated by fervent devotion to the Virgin Mary, Wernher freely reshaped and expanded his Latin source, Pseudo-Matthew, which he probably consulted in a “legendary”—a collection of saints’ lives.[] As Kurt Gärtner puts it: “Wernher transformed the events related succinctly in Pseudo-Matthew into lively and colorful representations of situations; he also knew how to motivate and depict the feelings that moved his characters. . . .”[] The poem survives today in a richly illustrated manuscript, made about 1220,[] that further transformed Wernher’s text, offering reader-viewers what Nikolaus Henkel calls “an effectively synaesthetic experience-space, in which text and images are each present in their own mode of functioning, but could be experienced together and in relation to one another.”[] This paper explores the reader-viewer’s experience in negotiating this illuminated manuscript.[] Applying the findings of neuroscience and cognitive studies[]—especially in the areas of perception, evocriticism (an approach that sees storytelling as an evolutionary adaptation), functions of mirror neurons, and cognitive blending—enables an understanding of how Wernher and the makers of this manuscript convey to reader-viewers the motivations and emotions of their characters.

This paper aims to demonstrate by means of an extended example some of the benefits to art history of making the cognitive turn.[] Cognitive studies has shown that the mind is “embodied in such a way that our conceptual systems draw largely upon the commonalities of our bodies and of the environments we live in.”[] These commonalities, being biologically based, have evolved and are shared through time. Thus, this inter-discipline of cognitive studies refuses the traditional Western conceptualization of mind and body as distinct and hierarchically ordered entities and speaks instead of the “embodied mind,” the “mind/brain,” or, as Elizabeth A. Wilson puts it, the “neurological body.” This body establishes “a relation between psyche and soma in which there is a mutuality of influence, a mutuality that is interminable and constitutive.”[] As a discipline enmeshed in the material, art history is especially well positioned to benefit from the findings of cognitive studies. For example, one-point perspective (the use of one vanishing point) encourages the notion that a disembodied eye enjoys an ideal, weightless position from which to survey a scene. Cognitive studies enables an understanding of the artifice of this notion by demonstrating that the conditions of embodiment—including, for example, the vertical axis of the body and the placement of the eyes in relation to it—crucially shape “the manner in which sensory information from the outside world is transformed into knowledge of the world.”[] Studies in perception show how the brain and body function together to shape what we think we see. Thus, to accept and apply the findings of empirical research in neuroscience and their interpretation as demonstrated in the range of approaches included in the umbrella term “cognitive studies” would fundamentally change our understanding of the ways humans experience art and would also provide art historians with significant new tools for analyzing response to their objects of study.

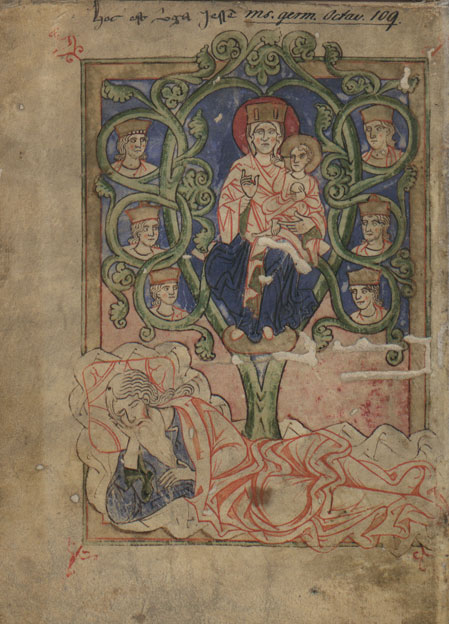

From its first page, the Cracow manuscript of Wernher’s Maria displays a propensity to convey meaning through and to the embodied mind. The manuscript opens with a full-page miniature visualizing the Tree of Jesse (Fig. 1), an image that derives from a Christian interpretation of Isaiah 11.1: “There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of its roots.” In the Latin Bible used in the Middle Ages, the word translated as “shoot” is “virga,” often rendered into English as “rod.” The Latin is a near-pun for “virgo,” meaning “virgin,” and was therefore interpreted by Christian exegetes as a reference to the Virgin Mary. By the time the Cracow manuscript was made, Bishop Fulbert of Chartres had written the responsory (or sacred chant), Stirps Jesse [the line or lineage of Jesse], which drew on Isaiah’s prophecy to create a genealogy for Mary, and Fulbert’s liturgical innovation had spread throughout Europe. The miniature in the Cracow manuscript visualizes the claim in Fulbert’s punning responsory, “The rod is the virgin mother. . .” [Virga dei genetrix virgo est],[] meaning Jesse’s lineage, visualized as a tree growing from his body, culminated in Mary herself (the rod) and her son Jesus (the branch). The inclusion of Jesse’s male descendents in the miniature insists on the participation of male bodies in the Incarnation. In its strong and simple composition, this miniature seems especially to assert that meaning arises from bodies, specifically from the intersecting axes of the horizontal male body of Jesse and the vertical female body of Mary. The bodily concerns of generation, birth, and the safe delivery and subsequent thriving of an infant with a distinguished lineage are introduced here as themes that resonate throughout this manuscript.

The image on the folio facing the Tree of Jesse continues Mary’s genealogy by visualizing Solomon, another of her ancestors.[] This folio again foregrounds bodies (Fig. 2). There is a shift, however, from the very stable and balanced composition of the Tree of Jesse to that of the Judgment of Solomon, which is filled with tension expressed through gesture and exchange of glance and dominated by the strongly unbalancing diagonals of scepter and sword. The story of the Judgment of Solomon found in I Kings 3:16-28 tells of two women who shared a home; each of them had recently given birth. When one mother lay on top of and smothered her child to death in the night, she falsely claimed that the surviving child was her own. The two women took their case to King Solomon, who ruled that, since neither woman would yield to the other, the living child should be bodily divided between them. The miniature visualizes the moment when the deceitful mother addresses the true mother in an endorsement of Solomon’s judgment. The words of her speech appear on the banderole rising from her uplifted hands: “It [the child] should be divided, as he [Solomon] says, so that it will be neither yours nor mine” [Man sol ez teilen als er giht. / daz mirs noh dir werde niht]. Typically, the miniatures in this manuscript include speech banderoles touching or held by the hands of speakers. The words thus animate the representations of their speakers, with the double result that speech is embodied and the reader-viewer’s sense of hearing is activated.[] As these words flow across the top of the page, they lead the reader-viewer’s eye to the huge sword in the executioner’s hand, raised in preparation for enacting the judgment that would inevitably place the living infant beside the dead one in the sarcophagus at Solomon’s feet. The atmosphere of anxiety that pervades this image exceeds that of the biblical text. There the actual mother of the living child speaks first, urging Solomon to let the child live and give it to the other woman; she thereby reveals the selfless love that convinces Solomon she is the true mother. Thus, the reader of I Kings anticipates a positive outcome even before learning that the deceitful mother urges the child’s slaughter. In the Cracow miniature, however, the true mother is mute, and Solomon, as if to visualize the way its words resound in his ears, appears to ponder the deceitful mother’s speech surrounding his head.

Visualization of spoken words moving through space is just one of the ways the engagement with space in this manuscript enhances the impact of the miniatures on reader-viewers. To gain greater access to this aspect of the reader-viewer’s experience of this illuminated manuscript, I begin with philosopher and aesthetician Richard Wollheim’s concept of “seeing-in,” which implies a dual response to a painting.[] One part of the experience comes from attending to the flat surface itself, and the other involves “seeing an object in the paint,”[] that is, the “registering of pictorial content.”[] Wollheim identifies “seeing-in” as a “special perceptual skill.”[] Cognitive philosopher Alva Noë’s study, Action in Perception, analyzes visual perception from the perspective of neuroscience. As Noë observes, far from being precisely focused and expansive, our perceptual field consists of a small, central area of sharp focus called the fovea; the rest of the field becomes progressively blurry towards the edges. The silver (now oxidized to black) and gold frames of the miniatures in this manuscript suggest just such a blurriness, creating a halo of light around the image that may enhance “seeing-in” by mimicking the actual perceptual field of the reader-viewer.

Further, according to what Noë calls the enactive view, perceptual experience depends upon sensorimotor knowledge acquired through physical action.[] “How they (merely) appear to be plus sensorimotor knowledge gives you things as they are.”[] Noë uses the example of seeing objects overlapping in such a way that one occludes part of another; in the miniature of the Judgment of Solomon, for example, the true mother’s body occludes part of the deceitful mother’s body. But we know that her occluded body is complete because we draw on our experience of having moved our bodies in space to enable multiple points of view. Thus, perception results from appearance plus sensorimotor knowledge, or knowledge acquired through physical action. Perception, in other words, is a bodily experience.

Neuroscience has discovered, Noë reports, that “Perception is not a process of drawing an internal representation, so it seems implausible that pictures depict by producing the sort of representation in us that the depicted scene would produce.”[] He goes on to offer an alternative: “The enactive approach suggests a rather different conception of pictorial representation. Pictures construct partial environments. They actually contain perspectival properties such as apparent shapes and sizes, but they contain them not as projections from actual things, but as static elements. Pictures depict because they correspond to a reality of which, as perceivers, we have a sensorimotor grasp. Pictures are a very simple (in some senses of simple) kind of virtual space. What a picture and the depicted scene have in common is that they prompt us to draw on a common class of sensorimotor skills.”[]

The preference for physical action in the miniatures in this manuscript especially activates these sensorimotor skills. As reader-viewers “see-in” to the miniatures, they make spaces for moving, gesturing figures and their interactions, and they understand those figures to have weight and three-dimensional substance. Further, the frequently employed device of extending elements of the image beyond the frame pushes the figures forward off the flat surface and into the reader-viewer’s space. Although Noë assumes the perspectival depth that most western art constructs, the miniatures in this manuscript ask also for what we might call “seeing-out.” This device reinforces the immediacy of the action in part by creating the illusion that the bodies depicted are co-present with the reader-viewer’s body. Sensing the overlapping as generative of space, the reader-viewer contemplating the miniature of the Judgment of Solomon experiences the figures of the true mother and child as pushed farthest from the frame and closest to herself. The frailty of an infant and its need for caring and wise mothering thus become concerns that the miniature forcefully communicates to the reader-viewer at the basic level of perception.

A cognitive approach to the Cracow manuscript must also take evolution seriously, as literary scholar Brian Boyd does in evocriticism, the approach he develops in On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction. In answering the question of what an evolutionary perspective might offer the student of narrative, Boyd answers that it “can stress the importance of attention itself, so often taken for granted in literary criticism. . . ."[] Attracting and maintaining attention to their narrative is the “storytellers’ first problem.” For Boyd, “attention precedes meaning, although an emerging intuition of meaning may also feed back into our interest in the story.”[] Those who designed and made the Cracow manuscript chose to attract the reader-viewer’s attention first through images—the facing full-page miniatures I have just discussed—thereby giving priority of place to the visual narrator whose depictions continue to appear throughout the manuscript. As we have seen, the first full-page miniature presents the protagonist of the narrative—Mary, with her child Jesus—as the apex of a centuries-long sequence of generation; it establishes their lineage. The next introduces text, not yet in the author’s long rhymed poems but in the deceitful mother’s direct speech, which raises anxiety about the survival of a child. Both genealogy and children were of great import to every noble family, aware of and proud of its ancestors and intent on continuing the line through the successful production of offspring. It is virtually certain that such a family commissioned the Cracow manuscript, and that its designers knew what would attract their clients’ attention.

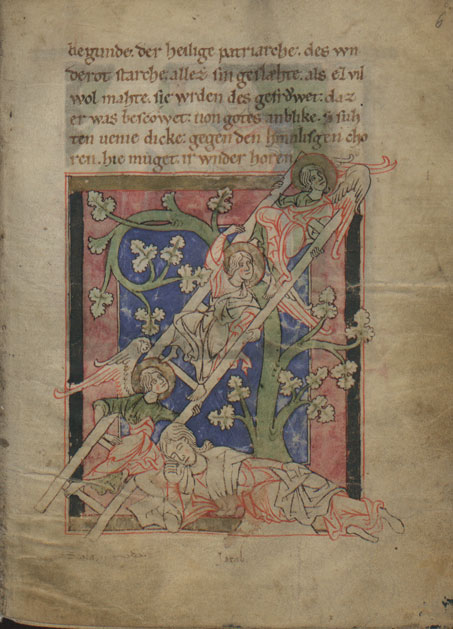

Only after these full-page miniatures does the verbal narrator enter, as Wernher’s text begins. He opens with praise of Mary and an invocation of her assistance[] before moving on to a description of his source, which he believed Saint Jerome had written. Then he starts his narrative with the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, relating the episodes of Jacob’s ladder and his wrestling with an angel. This section of text ends with the line directly above the miniature of Jacob’s ladder on folio 6r (Fig. 3): “here you may hear a wonder” [hie muget ir wnder horen; l. 260]. The word “horen” seems to refer to his story of Mary’s life, which is about to begin. It stimulates the sense of hearing just at the moment when the miniature engages the sense of sight. The gazes of all three angels in the miniature are fixed in the upward direction of their movement on the diagonally placed ladder. This miniature also engages the “special perceptual skill” of seeing-out, as the ladder overlaps the frame and pushes all of the angels—especially the one at the top of the ladder—into the reader-viewer’s space. Thus both angelic gazes and seeing-out focus attention on the upper right corner of the page, as if urging that it be turned in order to read-view more of the story.

Boyd makes a case for storytelling as an adaptive quality in evolution.[] For him, the large category is cognitive play, of which art—including the art of storytelling—is a subset. One of the chief functions of art is “to refine and retune our minds in modes central to human cognition—sight, sound, and sociality. . . .”[] Thus, “storytelling appeals to our social intelligence. It arises out of our intense interest in monitoring one another and out of our evolved capacity to understand one another through theory of mind.”[] The story that this manuscript tells would not have been new to reader-viewers, so the challenge is to engage their social intelligence by the way the story is interpreted, amplified, and visualized.

A transition at the opening of the next section of the first poem—“From the same kindred [as Jacob]” [Vz demselben chunne; l. 261] a child was born—connects the genealogy of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob with Mary, for the child is Joachim, who will be her father. The poem continues with the marriage of Mary’s parents, Joachim and Anne, leading to the birth of Mary and the story of her life through the Nativity and the return from Egypt after the death of Herod. This narrative is part of the central Christian myth. In ritual as celebrated in the cycle of the liturgical year, that myth is experienced episodically, as a series of key moments. The composition of Wernher’s poems appears to have been motivated in part by the introduction of new Marian feasts into the liturgy, for its three parts are organized around them: The Birth of the Virgin (Sept 8); the Annunciation (March 25); and the Nativity through Candlemas (when Mary and Joseph first took Jesus to the temple). But narrative has the option of filling in the gaps between these ritual, canonical moments. In the case of our poem, Wernher, a priest with pastoral responsibilities, explicitly addressed his poem to lay people. And though its stimulus may be liturgical, its concerns are not those of the fulltime religious but of the secular upper class.

One attraction of filling gaps in the biblical narrative through invention of new episodes, expansion of existing episodes, and character development may have been the way such material appeals to and develops what evolutionary psychologists have recognized as “our unique human level of theory of mind.” As Boyd puts it, “a fully human theory of mind requires a capacity for interpreting others not simply through outer actions and expressions, and even through inner states like goals, intentions, and desires, but uniquely also through beliefs.”[] Boyd argues that narrative is an evolutionary adaptation in humans that develops strategic intelligence by providing experience at “infer[ring] what others know in order to explain their desires and intentions with real precision.”[] Filling gaps stimulates reader-viewers to engage their theory of mind. Wernher’s development of the characters of Anne and Joachim and Mary and Joseph offers opportunities for reader-viewers to employ theory of mind in interpreting the married lives of these two couples, and thus to compare and comprehend more deeply the differences between the human institution of marriage and the unique marriage of Mary and Joseph.[] Illustrations also engage theory of mind: we learn to “understand social events and the sources of people’s knowledge” by “inferring others’ attention from reading the direction of their eyes, or their emotions from their expressions, or their knowledge from what they can perceive.”[]

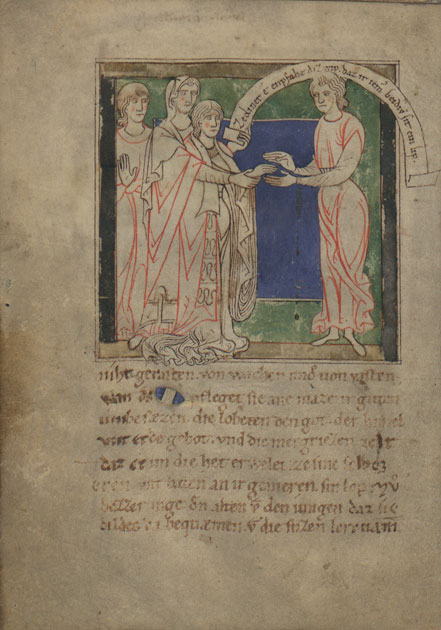

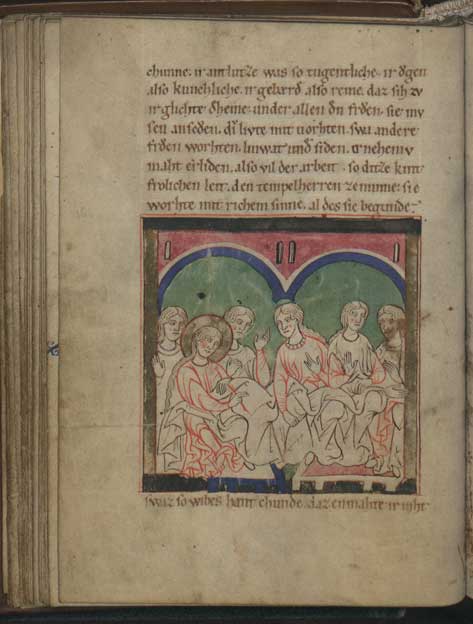

I turn next, then, to the ways the marriage of Joachim and Anne is constructed for reader-viewers. Wernher describes Joachim as a model of a man, “the best man on whom the sun ever shone” [v was der besten eine / den div sunne ie uberschêin; ll. 267-68], emphasizing his mind, sense, innocence, and holiness. He worked assiduously, exercised hard, and fasted. He also enjoyed religious narrative: as a young man, “He gladly sang and read / about his creator / the powerful old stories” [gerner sanch vnd las / von sinem schephaere / div starchen alten mære; ll. 296-98]. Visual emphasis falls on his generosity and charity; a miniature shows him as a wealthy man giving away two-thirds of his income. At the age of twenty, he chose to marry, for “he did not want to corrupt himself / with any kind of dissoluteness” [erne wolte sih niht uerbosen / mit deheiner getlose; ll. 339-40]. The miniature on folio 8v (Fig. 4) is inserted into the text passage describing his bride, Anne, whom he chose from the lineage of King David. She is chaste and beautiful, cultivates the giving of alms, and keeps vigils and fasts. The narrator places strong emphasis on their physical qualities. The first poem, in fact, uses the word for "body" twelve times in its 1,230 lines, six of them referencing Anne and three more referencing Joachim. The miniature reinforces the view of marriage as a union of bodies. The priest who is conducting the marriage ceremony holds a banderole out to Joachim, standing opposite him and Anne, containing these words: “Receive this woman for your own, so that you are both one body forever” [Ze diner e enpfahe diz wip. / daz ir iemer beidiv sit ein lip]. Cognitive psychologist David McNeill has shown that words accompanied by gestures are more profoundly retained in memory.[] In the miniature, gesture enacts the priest’s words, rendering them performative. He grasps Anne’s right wrist, indicating his power over her—that is, his authority to perform this ritual of marriage. The way his arm obscures the sight of hers virtually reduces her to his puppet. As he manipulates Anne’s hand, visually emphasized in silhouette against the blue background, the banderole with the priest’s words on it encircles Joachim and elicits his responding gesture of reaching with both hands to enclose Anne’s and thus to take possession of his bride.[] The gesture of enclosure and the phrase “one body forever” together create a normative marriage that will be sexually active, resulting in their daughter Mary. In their construction of Mary’s marriage to Joseph, within which, medieval Christians believed, she remained a virgin, the poet and the designer of this manuscript faced the challenge of shaping a relationship that would be understood by the reader-viewer as marriage while remaining within the parameters of orthodoxy.

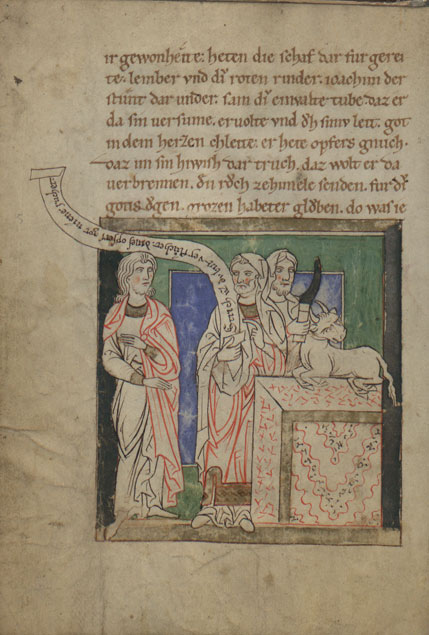

Following his sources, Wernher’s first poem goes on to describe the situation of Anne and Joachim twenty years after the marriage ceremony. They are still childless, a failure that a legal scholar interprets as due to God’s curse and therefore justification for sending Joachim away from the Temple (Fig. 5). The miniature emphasizes physical responses that engage theory of mind to understand the emotions of the characters. Joachim recoils physically from the scholar’s gesture and glance and, it appears, the words on his banderole: “Go away from here—you are accursed. God does not want your offerings” [Strich uz du bist verfluochet. / dines opfers got nîene ruchet]. The motion of the banderole from right to left seems to push Joachim back; as Messerer notes, “the banderole itself says, ‘Out’. . . .”[] To read the words on the banderole, the reader-viewer must literally turn the book upside down, as if to enact the total disruption of Joachim’s life resulting from the rejection of his offering. Such manipulation of the book makes reader-viewers aware of their own bodies even as they engage with the bodily experiences of others; it ensures that the sensorimotor system stays actively involved in perception.

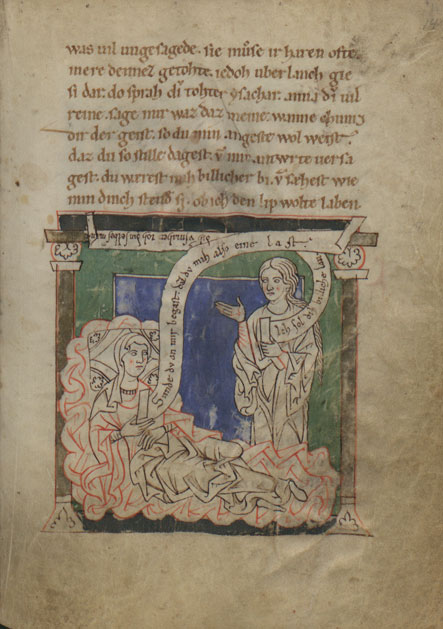

Anne interpreted Joachim’s departure as desertion of her and responded bodily: “The beautiful and good Lady Anne became pale and wan. Her bright color disappeared as her joy died” [do muse erbleichen danne / div schone vnd gute froe Anne/ ir liehtiv varwe uerdarp, / al ir frode erstarp; ll. 495-98]. In the miniature on folio 14r (Fig. 6), Anne, who has taken to her bed, accuses her maid of neglecting her. In a clash of banderoles that visualizes their lack of agreement, the woman replies, “It will be just of me to abandon you, for even your own husband spurns you” [Ich sol dih billiche lan. / dih versmahet ioh din selbes man]. Again the book must be turned, the maid’s upside-down words physically representing the inversion of the social hierarchy. Wernher’s presentation of this marriage offers to the book’s most likely owner—a noble laywoman—insights into both a marital relationship and the society within which it functions, as well as into the couple’s shame at infertility and joy when angels inform them that she has conceived. The poet and illustrator portray Anne and Joachim as eager to marry, marrying at the expected age in their society, and living in a normative marriage. They are sexually active and expect children, but are childless, for which they are rejected by their society until God intervenes and they have a daughter, Mary, whom they give to the Temple at the age of three. This extended portrait contrasts in significant ways with the next marriage the manuscript presents.

Wernher’s second poem begins with a description of Mary’s growing