INTERMISSION

NECKER

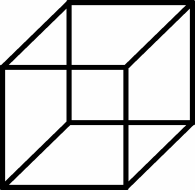

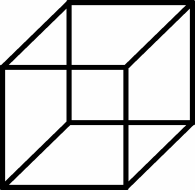

In my professional opinion, this is the best optical illusion in the world. It’s certainly the only one that I would have permanently tattooed on my body. It is a Necker cube. A wireframe outline of a cube. But look at for a little while and you should notice something strange. Whichever way it appeared at first, it seems to flip and change, a little longer and it flips back again. One moment you see the front face is coming out of the page upwards and rightwards. Seconds later, it is the opposite way around. The other square is now the front face, coming out downwards and leftwards. Then back, and so on ad infinitum or at least ad nauseam. The flipping never flipping stops. Trust me, I have had the tattoo for over five years now.

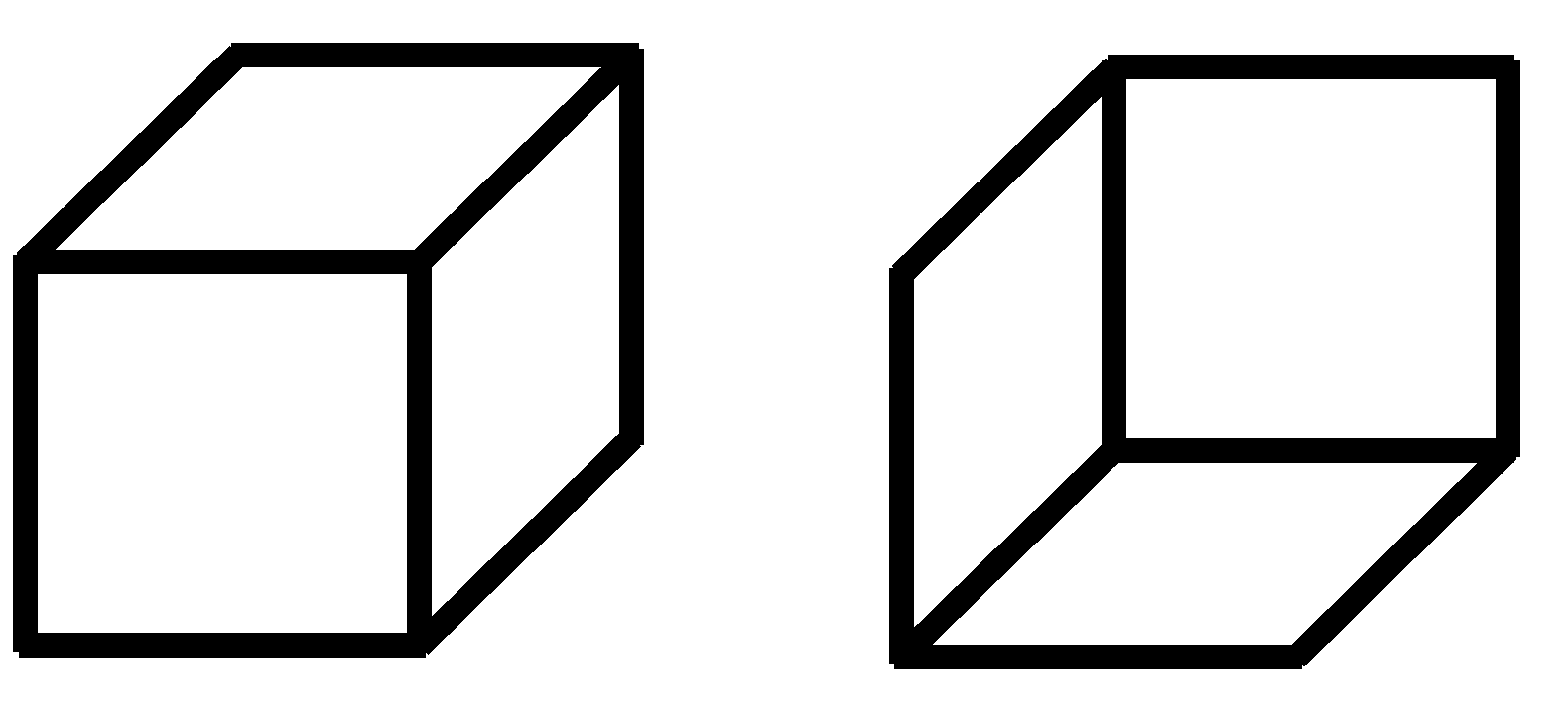

So what is happening? First, let’s be clear that they really are different. These are not two different views of the same cube. There’s one seen from above and one seen from below.

So which is right? Obviously, they are both right and that’s because in fact they are both wrong. What we are actually seeing isn’t a cube at all. It is some connected lines on a flat page that give the impression of a cube. Two cubes. The original figure is ambiguous. So on one level, the fact that what we see flips between these two possibilities is a fairly ordinary neurological fact. The visual parts of our brains see the lines on the page. They try to interpret this two-dimensional pattern. Elements of it are strongly suggestive of depth and what we construct is the cube that fits this. There are two possibilities so that’s what we see.

I don’t think anyone knows quite why it flips at that particular speed. But it might be more than a coincidence that 2-3 seconds is also the length of the personal ‘now’. The moving window in which we are constantly experiencing the present. Two seconds ago is the past, in two seconds time the future will arrive but right now this thin sliver of existence is happening. Or so it seems to feel.

There is only one window that you are looking out of. The Necker Cube suggests there can only ever be one. Try and divide your narrative into two conflicting frames and you’ll find it can’t be done. At first glance this is so obvious that it is often overlooked. But the fact we experience a unified self provides absolutely no explanation as to why we experience a unified self. Or why, as in the excluded simultaneity of these cubes, we can’t experience anything else.

At least not with a normal healthy brain or while trying to stay sane. Slice the huge bundle of fibres connecting the two hemispheres together and amazingly you’ll survive but there will be two dislocated parts to your personality rattling around inside you. It’s very hard to imagine what that feels like but take the right drugs and you can safely experience the disorientation of a kind. Dissociative anaesthetics can give you out of body experiences or twist time and space, while something as simple as too much alcohol can leave gaps in your memory of the night before. You were clearly there experiencing it, so why can’t you remember?

If you are unlucky enough to develop schizophrenia or even a simple skunk-induced psychosis, you can experience a disorientation of not knowing that your internal voices are your own. The illusion of a single-self is so strong, so essential that these experiences can drive you mad. Even when you know the cause, it doesn’t seem any less real. Self-knowledge doesn’t stop the depressed from feeling down. It doesn’t help someone with psychosis get a grip on himself or herself. Which self?

The Necker cube gives some clues as to how this self-governing mechanism is supposed to serve us. A well functioning consciousness balances the up with the down, the top with the bottom. Out there in the world is a single ambiguous figure that feeds into the system from the bottom upwards. A flat figure is passed up to higher dimensions, which use their knowledge to impose a fuller form. This happens with everything but rarely do we notice. Most things seem to us to have only one sensible interpretation. But this unruly cube breaks that illusion. Here it is clear that our brains have imposed the sense. Some abstract concepts have been handed down to ambiguous perceptions to tell them what we think of them. Many possible interpretations are always bubbling under the surface but only in rare circumstances does the debate take place before our very eyes.

It’s worth thinking about.