CHAPTER 4

UNDERSTANDING BUYER BEHAVIOR

No wonder they have become the target of marketing campaigns so sophisticated as to

make the kid-aimed pitches of yore look like, well, Mickey Mouse.

Marketers who had long ignored children now systematically pursue them-even

when the tykes are years away from being able to buy their products. "Ten years ago it

was cereal, candy, and toys. Today it's also computers and airl ines and hotels and

banks," says Julie Halpin, general manager of Saatchi & Saatchi Advertising's Kid Con-

nection Division. "A lot of people are turning to a whole segment of the population they

haven' t been talking to before."

Those businesses that have always targeted kids, such as fast-food restaurants and

toymakers, have stepped up their pitches, hoping to reach kids earlier and bind

more tightly. Movies , T-shirts, hamburger wrappers, and dolls are all part of the cross-

promotional blitz aimed at convincing kids to spend. The c umulative effect of initiating

children into a consumerist ethos at an early age may be profound. As kids take in the

world around them, many of their cultural encounters-from books to movies to TV-

have become little more than sales pitches. Even their classrooms are filled with corpo-

rate logos . To quote cl inical psychologist Mary Pipher, "Instead of transmitting a sense

of who we are and what we hold important, today 's marketing-driven culture is instilling

in them the sense that little exists without a sales pitch attached and that self-worth is

somethi ng you buy at a shopping mall."

Some wonder if marketers are creating a relationship with consumers too soo;, and

for all the wrong reasons.

Sou rces: David Leonhardt. "Hey

Buy This," Business Week. June 30. 1997. p. 65-67; Larry Armstrong. "Pssst! Come Inlo My Web." Bll siness Week. Ju ne 30,1 997. p. 67; Tom McGee, "Gening Inside Kid s Heads," American Demographics, January 1997, pp. 53- 59: "Kids These Days," Ame rican

April 2000, pp. 9- 10; Joan Raymond, "Kids Just Wanna Have

Fun," American Demographics, Fe bru ary 2000, pp . 57- 61.

INTRODUCTION

As noted, many of the parents of today's kids are the baby boomers marketers have been

tracking for over forty years. Primarily, their importance is based on their group's enor-

mous size. Just as important, however, is that they have a great deal in common; some demo-

graphics, such as age, income, and health; some shared

such as college for their

children, retirement, and diminishing health; and some behaviors such as voting Republi-

can, eati ng out, and buying expensive walking shoes . Nevertheless, they still remain indi-

viduals who were brought up in a unique fam ily and retain a personal way of thinking and

behaving. The ultimate challenge facing marketers is to understand the buyer both as an

individual and as a member of society so that the buyer's needs are met by the product offered

by the marketer. The purpose of this chapter is to present a discuss ion of several of the key

buyer behaviors considered important to marketers .

BUYER BEHAVIOR AND EXCHANGE

As noted in an earlier chapter, the relationship between the buyer and the seller exists through a phenomenon called a marke t exchange. The exchange process allows the parties to assess the relative trade-offs they mu st make to satisfy their respective needs and wants. For the

BEHAVIOR AS PROBLEM SOLVING

75

marketer, analysis of these trade-offs is guided by company polices and objectives. For exam-

ple, a company may engage in exchanges only when the profit margin is 10% or greater.

The

the other member in the exchange, also has personal policies and objectives that

guide their responses in an exchange. Unfortunately, buyers seldom write down their per-

sonal policies and objectives. Even more likely, they often don't understand what prompts

them to behave in a particular manner. This is the mystery or the "black box" of buyer behavior that makes the exchange process so unpredictable and difficult for marketers to understand.

Buyers are essential partners in the exchange process. Without them, exchanges would

stop. They are the focus of successful marketing ; their needs and wants are the reason for

marketing. Without an understanding of buyer behavior, the market offering cannot possi-

bly be tailored to the demands of potential buyers. When potential buyers are not satisfied,

exchange falters and the goals of the marketer cannot be met. As long as buyers have free

choice and competitive offerings from which to choose, they are ultimately in control of

the marketplace.

A market can be defined as a group of potential buyers with needs and wants and the

purchasing power to satisfy them. The potential buyers, in commercial situations, "vote"

(with their dollars) for the market offering that they feel best meets their needs. An under-

standing of how they arrive at a decision allows the marketer to build an offering that will

attract buyers . Two of the key questions that a marketer needs to answer relative to buyer

behavior are:

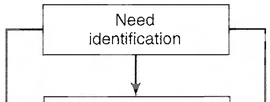

1. How do potential buyers go about making purchase decisions?

2. What factors influence their decision process and in what way?

The answers to these two questions form the basis for target market selection, and, ulti-

mately, the design of a market offering.

When we use the term

we are referring to an individual, group, or organi-

zation that engages in market exchange. In fact, there are differences in the characteristics

of these three entities and how they behave in an exchange. Therefore, individuals and groups

are traditionally placed in the consumer category, while organization is the second category. Let us now

to consumer decision making.

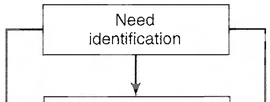

BUYER BEHAVIOR AS PROBLEM SOLVING

Consumer behavior refers to buyers who are purchasing for personal, family, or group use.

Consumer behavior can be thought of as the combination of efforts and results related to

the consumer's need to solve problems. Consumer problem solving is triggered by the iden-

tification of some unmet need . A family consumes all of the milk in the house or the tires

on the family care wear out or the bowling team is planning an end-of-the-season picnic.

This presents the person with a problem which must be solved. Problems can be viewed

in terms of two types of needs: physical (such as a need for food) or psychological (for

example, the need to be accepted by others).

Although the difference is a subtle one, there is some benefit in distinguishing between

needs and wants. A need is a basic deficiency given a particular essential item. You need

food,

air, security, and so forth. A want is placing certain personal criteria as to how

that need must be

Therefore, when we are hungry, we often have a specific food

item in mind. Consequently, a teenager will lament to a frustrated parent that there is noth-

ing

eat, standing in front of a full refrigerator. Most of marketing is in the want-fulfilling

business, not the need-fuifilling business. Timex doesn't want you to buy just any watch,

they want you to want a Timex brand watch. Likewise, Ralph Lauren wants you to want

76