INTRODUCTION TO SUTURING

WHAT IS A SUTURE?

The word "suture" describes any strand of material used to ligate (tie) blood vessels or approximate (bring close together) tissues. Sutures are used to close wounds

SUTURE COMPONENTS

A) THREAD

B) NEEDLE

TYPES OF THREAD

Surgical suture material can be classified on the basis of the characteristics absorbability, origin of material and thread structure.

They can be absorbable or nonabsorbable; synthetic or natural; mono-or multi-filamentous.

ABSORPTION

Absorption can occur enzymatically, as with catgut, or hydrolytically, as with the absorbable synthetic polymers. An important measure of absorbability is the absorption time or halflife, which is defined as the time required for the tensile strength of a material to be reduced to half its original value. Dissolution time is the time that elapses before a thread is completely dissolved. These times are influenced by a large number of factors including thread thickness, type of tissue, and, not least, the general condition of the patient.

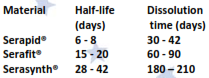

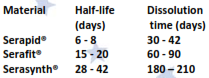

The most important absorption and dissolution times are shown in the following table:

Approximate absorption times of synthetic suture materials

ORIGIN OF MATERIAL

Suture materials can be classified as being of natural or synthetic origin. The former include silk and catgut. The other main groups of suture materials are those produced from synthetic polymers such as polyamide, polyolefines and polyesters. This group also includes absorbable polymers derived from polyglycolic acid.

STRUCTURE OF THREAD

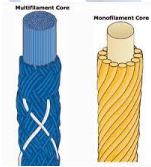

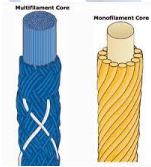

Monofilament and multifilament thread structures are distinguished.

Monofilament threads

Synthetic monofilament threads are produced by a special extrusion process in which molten plastic is extruded under high pressure through fine spinnerets. The monofilament structure is used mostly for thinner threads. With thicker threads the wiriness that is a characteristic of all monofilament threads impairs handling and in particular renders knot-tying more difficult. Because of their smooth, closed surface and completely closed interior, monofilament threads have no capillarity. On the other hand, the ease with which they pass through tissue is unsurpassed.

Multifilament threads

Multifilament threads are composed of many fine individual threads either twisted or braided together. The direction of the twist is generally right-handed. Twisted multifilament threads include e.g. silk threads. All twisted threads show considerable variation in diameter. Their surface is mostly rough. The longitudinal orientation of the individual filaments within the thread results in relatively high capillarity. In braided threads the individual filaments lie more or less obliquely to the longitudinal axis of the thread. This tends to impede the passage of fluid. The capillarity of braided threads is therefore less than that of twisted threads. Multifilament threads have a rough surface that impairs passage through tissue but results in considerably better knot holding security. Multifilament threads are generally coated. The coating smoothes out the irregular surface and thus facilitates passage through tissue without impairing knot-holding security. Coated multifilament threads are less stiff and wiry than monofilament threads. The coating also reduces capillarity.

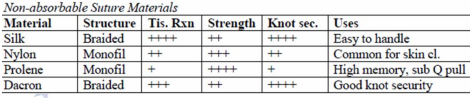

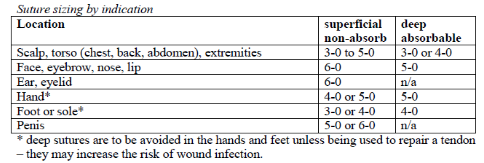

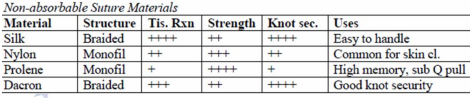

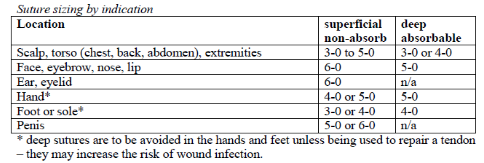

SUTURE SELECTION

- Do not use dyed sutures on the skin

- Use monofilament on the skin as multifilament harbor BACTERIA

- Nonabsorbable cause less scarring but must be removed

- Plus sutures (monocryl for E. coli, Klebsiella)

- Location and layer, patient factors, strength, healing, site and availability

- Absorbable for GI, urinary or biliary

- Nonabsorbable or extended for up to 6 mos for skin, tendons, fascia

- Cosmetics = monofilament or subcuticular

- Ligatures usually absorbable

NEEDLES

Necessary for the placement of sutures in tissue, surgical needles must be designed to carry suture material through tissue with minimal trauma. They must be sharp enough to penetrate tissue with minimal resistance. They should be rigid enough to resist bending, yet flexible enough to bend before breaking. They must be sterile and corrosion-resistant to prevent introduction of microorganisms or foreign bodies into the wound.

The best surgical needles are:

- Made of high quality stainless steel.

- As slim as possible without compromising strength.

- Stable in the grasp of a needleholder.

- Able to carry suture material through tissue with minimal trauma.

- Sharp enough to penetrate tissue with minimal resistance.

- Rigid enough to resist bending, yet ductile enough to resist breaking during surgery.

- Sterile and corrosion-resistant to prevent introduction of microorganisms or foreign materials into the wound.

Note:

The penetration force of a needle depends in the first line on its shape and the polished and etched microsection of the tip, and less on the quality of the steel

- Ductility: how often a needle can be bent back and forth before it breaks

- Austenite: microstructure of steel. Austenitic microstructure is face-centred cubic, forms at high temperatures above approx. 1300°C and only remains stable at these temperatures. The addition of alloy components such as nickel and manganese, however, maintains this structure at room temperature.

- Martensite: microstructure of steel. Martensitic microstructure forms at high temperatures. It is extremely hard and the structure can be maintained by rapid cooling (“quenching”).