Environmental History in the Classroom: Yellow Fever as a Case Study

In early twentieth-century Cuba, the U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission, led by Walter Reed, discovered that mosquitoes were responsible for the spread of yellow fever across the globe. Prior to Reed's findings, people had lived in fear of a disease that appeared to strike with no warning or logic. Yellow fever, characterized by a high fever, black vomit, and skin yellowing, often proved fatal. In the 1790s numerous cities in the U.S. were crippled by the fever and the epidemics returned at regular intervals until 1905, "the last American yellow fever epidemic"(Hays, 265). In two letters to her sister (October 27, 1878 and January 27, 1879) and one (October 13, 1878) to the Memphis Telegram, nurse Kezia Payne DePelchin describes the yellow fever outbreak of 1878-1879 that spread across Mississippi, Tennessee, and Louisiana, leading to the deaths of an estimated 4,100 people in Mississippi alone (Nuwer, 126). These three documents are physically housed in Rice University's Woodson Research Center, but are made available online through the ‘Our Americas’ Archive Partnership (a digital collaboration on the hemispheric Americas). While accounts of yellow fever are not overly rare, DePelchin’s perspective is unique in that she managed to survive close contact with infected individuals during numerous epidemics due to her immunity acquired by surviving the illness early in life. While there are a variety of ways to approach her writings, this module contends that DePelchin's writings are a resource for educators interested in using the lens of environmental history as a way to describe the economic growth, the scientific advances, and the development of civic involvement that occurred in the U.S. during the 1870s.

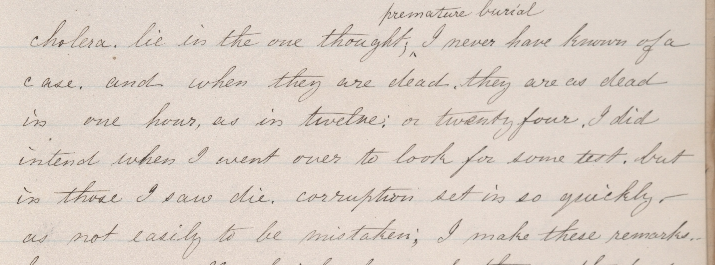

Just as social history, an outgrowth of the 1970s, is now considered a commonplace part of college and high school history textbooks, environmental history, one of the newest and most engaging forms of historical inquiry, is gradually being incorporated in the classroom. Environmental historians use primary documents to explore how the environment (insects, natural disasters, diseases, etc.) impacts and shapes human history in a variety of ways. For an example of a good, recent environmental history see Matthew Mulcahy’s Hurricanes and Society (2006) (see full biographical details below). To begin with, educators can emphasize how, although she did not realize it at the time, DePelchin, through her letters, constructed an environmental history of the 1878-1879 yellow fever outbreak. She traced the characteristics of the illness, accounted for the “collection” of the victims, and wondered why citizens so quickly began to “dance over the ashes” of the dead. DePelchin eventually returned back to Texas, but she wrote to her sister that “the remembrance of the awful scenes of the great epidemic have cast a shadow on my heart that will never pass away.” A single lecture can focus on DePelchin or environmental history can serve as a theme carried throughout the entire course.

Educators would probably get the most benefit from introducing DePelchin’s letters during a discussion of 1870s America, a section that appears under the title of “Growth as an Economic Power” in many U.S. History textbooks. In addition, the 1870s is known by historians as a period marked by city development and scientific innovation. City boosters lauded the benefits of their individual cities in order to gain revenue, while innovators such as Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison invented the telephone and phonograph, respectively. This connects to the DePelchin letters because science had yet to solve the mystery of yellow fever and the letters describe in detail the successes and failures of the various curative methods attempted by nurses and doctors. To trace the evolution of medical approaches to yellow fever, and to put the 1878-1879 epidemic in perspective, educators can assign sections or particular chapters from J. N. Hays’s Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History (2005). Then, a discussion can take place focusing on how treatments for yellow fever changed over time. Students can also be asked to bring in articles on modern diseases, such as SARS, and to connect how our present-day search for answers parallels that of the past. If the class is large and additional illness essays are needed, educators can reference Michael Oldstone’s Viruses, Plagues, and History (1998).

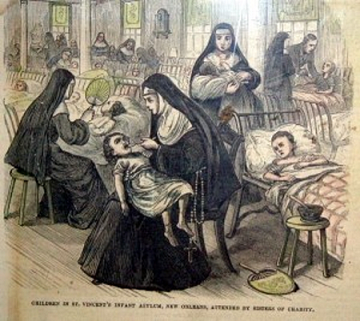

It is also interesting to note how civic organizations, one way that we prevent and treat illness in the present day, were only starting to develop in the 1870s. DePelchin was drawn in to help as a nurse with the assistance of a larger medical group, but very few cities across the South had created medical or health boards. For a strong elucidation of this argument useful for educators hoping to emphasize the civic development of the South, see Plague Among the Magnolias (2009) where Deanne Stephens Nuwer traces the “expanded role played by charities and local government agencies” during the 1878 outbreak (xi). The concentration of resources made possible by the growth of cities allowed for these advances, but epidemics in cities also created unique problems. Students can be asked to identify how city life could exacerbate already deadly disease conditions. For example, students can investigate the city-based similarities between the 1793 Philadelphia outbreak (see J.H. Powell’s Bring Out Your Dead (1949)) and the 1853 New Orleans outbreak (see John Duffy’s Sword of Pestilence (1966)).

While comparing city environments is important, this module would be remiss if it did not mention the possibilities inherent in making a global comparison of yellow fever outbreaks. Caribbean historians have been innovators in environmental history and their efforts have produced a substantial number of worthy resources. Richard Sheridan’s Doctors and Slaves (1985) represents one of the more substantial works and it can facilitate a comparison of U.S./West Indies medical cultures, as evident via the treatment of a variety of illnesses, including yellow fever.

On a final note, yellow fever provides educators a rare opportunity to convey an intangible aspect of history to students, the way that people in the past experienced and felt fear. It is often difficult to explain in a classroom how people decades or centuries ago were motivated by fear in ways similar to, and different from, people today. For example, fear led to flight being the most commonly chosen method of avoiding yellow fever, as evidenced by DePelchin’s writings. Visuals can help convey the influence of emotions on human history. In particular, PBS has an informative and dynamic one-hour film entitled, "The Great Fever".

Bibliography

Duffy, John. Sword of Pestilence: The New Orleans Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1853. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1966.

Hays, J.N. Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts of Human History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC CLIO, 2005.

Mulcahy, Matthew. Hurricanes and Society in the British Greater Caribbean, 1624-1783. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Nuwer, Deanne Stephens. Plague Among the Magnolias: The 1878 Yellow Fever Epidemic in Mississippi. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama, 2009.

Oldstone, Michael. Viruses, Plagues, and History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Powell, J. H. Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1949.

Sheridan, Richard. Doctors and Slaves: A Medical and Demographic History of Slavery in the British West Indies, 1680-1834. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.