CHAPTER V

AN IMPERIAL GARDEN-PARTY

Silk dresses and frock-coats--A disappointed Colonel--The Royal procession--The chrysanthemums--I am presented--A Japanese play--Japanese royal sport--The Mikado and his subjects.

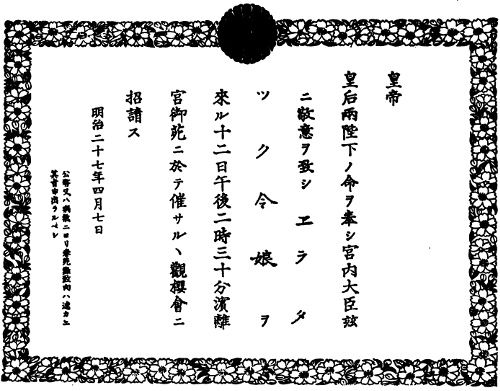

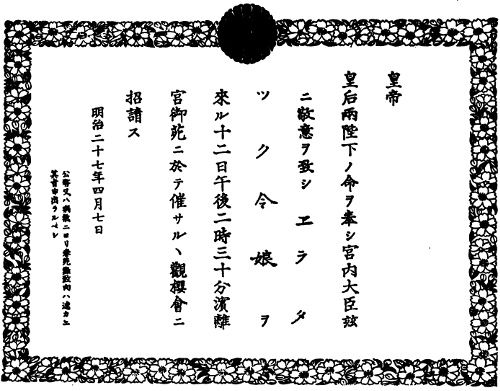

We had been in Japan nearly three months when we were invited to attend the chrysanthemum garden-party given by the Emperor and Empress each November in honour of His Majesty’s birthday. Invitations are sent but a few days beforehand, as the date of the party depends on the state of the chrysanthemums. Only the Corps Diplomatique, Government officials, and a few globe-trotters are invited; the latter obtain their invitations through their own Legations. As it is almost the only occasion when Their Imperial Majesties are seen in public, I was delighted at the idea of going.

Our invitation-cards were very large and thick, with the Imperial crest at the top and a gold border of chrysanthemums. The writing was in Japanese characters, but enclosed in the same envelope was a slip of paper in French, saying that ladies were to appear in silk dresses and gentlemen in frock-coats and top-hats. Not possessing a suitable garment, I was puzzled at first to know what to wear, but I eventually succeeded, with the assistance of one of the little Chinese tailors, in converting a blue silk evening frock into one suitable for the garden-party.

The day was fortunately fine and exceptionally warm for November. We started from the Imperial Hotel in Tokio, where we were staying, at about half-past one, Colonel S. and his wife from Hongkong sharing a carriage with us.

Japanese horses are willing little beasts, not much larger than ponies. Our coachman drove full gallop through the streets, and the ‘betto,’ or footman, ran along in front shouting at the crowds to get out of the way. How an accident was avoided I do not know, as the streets seem to be the playground of all the children in Tokio; and I thought several of the little doll-like figures must have been run over. Our driver and betto wore dark blue linen with a crest embroidered on their backs, and large white pith hats fastened under the chin with a strap.

OUR INVITATION-CARDS WERE VERY LARGE AND THICK.

Colonel S., who was only passing through Japan on his way to England, had no frock-coat with him, but in his well-cut dark suit and top-hat we all thought he could not fail to pass muster. We were mistaken, however. On our arrival at the palace, we were ushered into a large hall where a row of officials in blue-and-gold uniforms were waiting to inspect us. As the gallant Colonel passed up the room, two of the officials stepped up to him, pointed to his frockless coat, began gesticulating wildly and talking rapidly in Japanese, of which the Colonel did not understand a word. My father, who speaks Japanese, attempted to explain matters, but without success. The discomfited and disappointed officer had to retire, leaving his wife, who fortunately had on the required silk dress, to go on with us alone.

After walking about half a mile through the grounds, which are very beautiful, over little bridges and up little winding paths, we arrived at some large tents, where the chrysanthemums were on show. Numerous groups of people were dotted about--Japanese officers and officials in uniform; others in grotesquely-cut frock-coats and opera-hats; their wives and daughters in European dress; also members of the different legations and consulates. I could not help thinking how far better the little Japanese ladies would have looked in their own national costume, but European dress is the strict order at Court. The scene was a very picturesque and animated one, and great excitement prevailed when, about half-past two, the Emperor and Empress were announced to be coming. The Corps Diplomatique arranged themselves in line--first the French Minister as doyen, with his wife, daughters, secretaries, and Belgian staff; then followed the English, German, American, Spanish, Dutch, Italian, Russian, Chinese and Korean diplomats, the two latter looking very picturesque in their quaint head-dresses and long robes. The remainder of the guests stood in a group a little apart.

As the Royal procession appeared in sight, walking slowly up the winding paths, the band played the Japanese National Anthem and there was dead silence amongst the crowd.

The Emperor walked first in full General’s uniform, quite alone. He is a tall man for a Japanese, stout and extremely plain. He had a stern, somewhat forbidding expression, which he always wore in public; and as Sir Edwin Arnold says, ‘The slightest bend of his brow in salutation appears to be the result of superhuman effort of reluctant will.’ Yet he is idolized by his people; it is said that his power is enormous, while no one knows how he controls and rules the Empire from the privacy of his walled-in palace.

Behind him walked the Empress, quite alone also, dressed in crimson brocaded satin with a little Paris bonnet to match, followed by her ladies-in-waiting and the Court officials and Ministers of State--amongst them the Marquess Ito, Count Oyama, and General Yamagata, all well-known names in Europe at the present time.

They bowed low as they passed us, and we kept up a succession of bobs and curtsies until we joined into line and followed the procession into the flower-tents.

THE GARDENS ARE VERY BEAUTIFUL.

Apparently the great feature at a chrysanthemum show, from a Japanese point of view, is not the size and shape of each flower, but the number of blossoms on a plant flowering at the same time. Three of the tents contained but one enormous plant in each; with from one to two thousand blooms all the same size and colour. We were told that one of these plants alone requires a gardener’s entire time to look after it, as the difficulty is to get all the flowers to perfection at once. In other tents, chrysanthemums with small, different-coloured flowers had been trained over wires to represent figures of people and animals, more curious than beautiful.

After the flowers had been inspected, the Emperor and Empress entered a large tent, where the presentations were made. Each Legation went in turn to felicitate the Emperor on his birthday and to bow to the Empress. All had to walk backwards out of the tent past the Court ladies and officials--not an easy task. With some the Emperor said a few words. His face when smiling lighted up, changing his morose expression to one of almost benevolence. I own to feeling horribly nervous when my turn came to be presented by our Minister’s wife, and breathed a sigh of relief when I returned safe and sound from the Royal tent without having utterly disgraced myself by tumbling over my train, or knocking down one of the little officials who were stationed at every available corner.

Small tables were placed about on the grass, and we were offered sandwiches of foie-gras, caviare and chicken, creams, ices, and champagne.

It was amusing to watch some of the Japanese guests, not only partaking of a hearty meal, but quietly secreting sweetmeats and cakes in their pockets, probably for some little child at home.

The royal party, after having some light refreshment at a table a little apart from the rest, then rose to leave. The National Anthem was again played, and we all followed as we liked.

At one end of the gardens a play was going on. No stage, only a ring of chairs and a big sheet. The actors were being made up and dressed in sight of everyone. Men clothed in black, with masks, arranged the scenes, and were supposed to be invisible. The play was ‘The Forty-seven Ronins.’ All the Japanese in the audience held handkerchiefs to their eyes and wept copiously, although I failed to see anything at all pathetic in the wild gesticulations of the actors. The famous Danjiro was there--the Irving of Japan. Amongst the audience the poetess of the Empress was pointed out to us, a curiously shrivelled-up little lady in a stiff green-and-white brocade, with a large bustle, green shoes and stockings, and a wonderful erection of flowers and feathers on her head. This costume must have done duty on these occasions for many years, to judge by its antique style; but the little lady was evidently very proud of her toilette. Three of the young Princesses, pretty little girls, with round, merry faces and bright dark eyes, were also spectators. We did not see the Crown Prince, a delicate, consumptive youth, already married and a father. The Empress is not his mother. She is childless, but the Japanese law has sanctioned the adoption of this boy, the son of one of the Emperor’s unofficial wives, as heir to the throne. I am told, however, that the Crown Prince looks upon the Empress as his mother.

The Emperor has five unofficial wives, all ladies of good family, who have separate establishments in the palace grounds, but are never seen in public; in fact, of the private life of the palace the outside world knows nothing. Japan is one of the oldest dynasties in the world, and the Japanese were living very much as they do now, except for electric light and European dress, when we Westerners were savages in blue paint and feathers.

In another part of the palace grounds are the duck-ponds and decoys. The killing of these wild duck, which come in great quantities every winter to the moat and decoys, is held to be a royal sport in Japan, and they are considered more or less sacred. The official who showed us the decoy begged us to keep quite silent, and we walked on tiptoe, in single file, up a narrow path to a small wooden hut, where we were allowed to peep at the sacred birds through little slits in the wood. There were already great numbers of them collected together, all apparently quite tame. The ‘sport’ is this: There are long dykes, with a high net at the end. The ‘sportsmen’ stand on either side with large hand-nets, and the duck are driven into the dykes from the pond, and, not being able to get out, rise, when they are caught in the nets and their necks wrung. It is supposed to be a great disgrace to miss a bird.

We were afterwards taken to the aviaries, where we saw a collection of birds of every description, from a Cochin-China hen to an eagle. There was a parrot there which is known to be a hundred and twenty years old, possibly more. They were all beautifully kept and cared for. One of the attendants amused us by saying: ‘Is it not a sign of the Emperor’s good heart to have so many birds?’ But when we asked him how often His Majesty came to see them, he said: ‘Oh, he never comes here.’

The Imperial Palace is an enormous building of wood surrounded by a moat. The rooms are decorated with valuable paintings, the walls hung with ‘kakimomos’ by celebrated Japanese artists, and old embroideries; the Emperor also possesses a priceless collection of gold lacquer and ivories. The palace is fitted up with electric light, but the Emperor considers it dangerous, so the rooms are lighted by thousands of candles.

The palace grounds cover many acres in the centre of Tokio--the highest position in the city. Imperial etiquette forbids that the ruler of the Land of the Rising Sun should be looked down upon from any point of view; therefore from his palace windows he can look down upon every part of the city. For the same reason, on the rare occasions when His Majesty passes through the streets of the city, orders are given for all the upstair window-blinds to be lowered.

BUTCHER’S.

UMBRELLA SHOP.

QUAINT SIGNBOARDS IN SOME OF THE STREETS, TOKIO.

Formerly men, women, and children fell on their faces as the royal carriage passed by; now they only bow low, in token of their awe and respect.

POULTRY AND EGG SHOP.

JAPANESE TAILOR.

QUAINT SIGNBOARDS IN SOME OF THE STREETS, TOKIO.

Soon after our arrival in Tokio I had a rather startling experience. I was standing in one of the streets to watch the Emperor drive past in his carriage, when suddenly my hat was wrenched off my head, and I was pushed forward violently by some heavy hand. On looking round, I saw an officious little policeman glaring at me, my poor hat in his clutches. Not until the procession had disappeared from view could I understand what had happened, but remained meek and hatless. It seems the little man considered my attitude towards his Sovereign was not sufficiently humble, and took this somewhat drastic way of correcting me. I must say this was the only occasion when I have experienced the slightest rudeness or incivility in the streets of a Japanese town, although I do not consider that foreigners are altogether beloved in Japan.

An artist who painted the portraits of the Emperor and Empress told me that he had been obliged to do them almost entirely from photographs, as their Imperial Majesties are far too sacred to pose as models. On one occasion he persuaded one of the Court officials to allow him to stand behind a curtain at a Royal banquet. Through the curtain he made a little hole, and was thus enabled to get a glimpse at the Emperor. Another time he waited patiently for hours at some place where the Empress was to pass; but on her arrival all present were obliged to bow their heads in obeisance, and the poor man could see nothing. However, the likenesses were considered good, and the artist received three thousand dollars for each picture, as well as a large medal, of which he is very proud.