CHAPTER VII

JAPANESE CHILDREN

Boys and girls--Games--The Feast of Dolls--School life--The ‘Hina Matsuri’--The Feast of the Carp--The ‘Bon Matsuri,’ the festival for dead children.

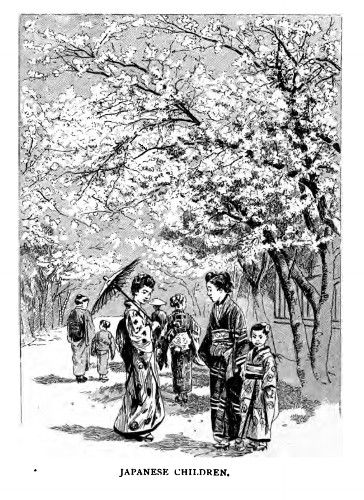

There is nothing more delightful in Japan than the children. Japan has been called ‘the Paradise for Babies,’ and the Japanese ‘a nation at play.’ Certainly these titles seemed to me appropriate as I took my first drive through the narrow Japanese streets, and saw at every turn the crowds of happy-faced little beings, either flying huge kites--whose long strings got sadly in the way of our rickshaws, though no one seemed to care--or spinning tops on the pavement, a fatal practice to short-sighted pedestrians.

How picturesque they looked toddling about in their bright-coloured kimonos and high wooden clogs, with a baby almost as big as themselves firmly secured on their backs, the rider and ridden sometimes so near of an age that one almost fancied they must be taking turns and carrying one another!

‘HOW PICTURESQUE THEY LOOKED!’

The babies, too, appeared to enjoy the fun as much as anyone, which was fortunate, as, willing or unwilling, they had to join in all the games of their elder brothers and sisters, and one wondered how on earth it was their little heads didn’t roll off as they rocked backwards and forwards, and up and down, in time to the rapid movements of the game their elders were playing.

Little girls, too small to carry real babies, had big dolls strapped on their backs, and it was really difficult to distinguish the live article from the imitation. No wonder their backs become bent nearly double by the time they are old women--they age very quickly do the women in the Far East--but they are wonderfully fascinating when young, with their curious, old-fashioned manners, their marvellous self-possession, and the politeness and dignity with which they comport themselves on every occasion. They have but one drawback, and that I must confess is a very serious one--namely, the total absence of pocket-handkerchiefs; and somehow they always seem to have colds! I think I need say no more.

There are many strange and original customs relating to the management and bringing up of children in Japan. Boys are the most thought of, as is universally the case all over the East, but not to the same extent as in other Eastern countries.

‘On the birth of a son there is great rejoicing in a family. Two fans are presented to the infant by his godparent, representing courage. When he is thirty days old he is taken to a temple to receive his name. Three names are written on separate bits of paper and given to a priest, who, asking the gods to direct the choice, throws the slips into the air, and the first falling to earth is supposed to contain the name the gods approve of, and is consequently given to the child.

‘Other names are added during the boy’s life--on his fifteenth birthday, on his marriage, and one is given to him after death by his relations.

‘A boy’s head is clean-shaven until he is five years old, with the exception of four little tufts of hair--one in front, one behind, and one at each side of his head. On his fifth birthday the function of the “hakama” takes place--the child, in other words, goes into trousers. A godparent is appointed for this important event, who presents his godson with three gifts--a false sword, a wooden spear, and a ceremonial dress embroidered with storks, tortoises, branches of fir, bamboo-twigs, and cherry-blossom--all emblems of good luck and long life. From that date his hair is allowed to grow, though it is generally very closely cropped in French fashion.

‘On his fifteenth birthday the last and most important function is celebrated--"the Ceremony of the Cap"--when a new godparent is chosen, the boy receives his second name, and he attains his majority.’[C]

C. Siebold.

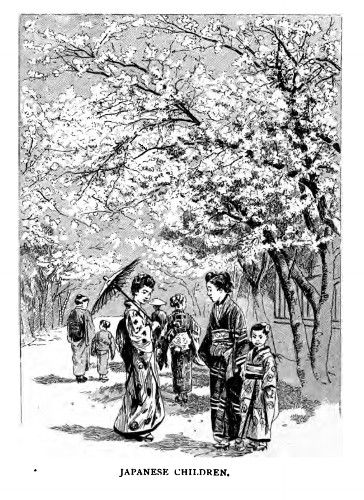

JAPANESE CHILDREN.

We are also told by Siebold that it was the custom of the ancients, on the birth of a female child, to let it lie on the floor for the space of three days, and in this way to show the likening of the man to heaven and the woman to earth. This custom has fortunately been abolished, with many other cruel and barbarous practices, and female children are no longer neglected.

When a daughter is born in a house, a godparent is chosen, who presents the baby with a shell of paint, implying beauty. A pair of ‘hina,’ or images, are also purchased for the little girl, which she plays with until she is grown up. When she is married her hina are taken with her to her husband’s house, and she gives them to her children, adding to the stock as her family increases.

Dolls occupy a very important part in the life of a little girl. They are not merely playthings to be thrown away and discarded at will; on the contrary, they are considered ‘heirlooms’ in a family, and carefully guarded and treasured for generations. I really think an ‘ichi ban,’ or best doll, receives much more care and attention than the real baby, who from its earliest infancy, as I have before remarked, is made to share in all the work and play of its elders, with no regard to its own feelings or wishes.

The ‘Hina Matsuri,’ or the Feast of Dolls, takes place annually on March 3, and lasts about a week. I remember paying a very interesting visit to the wife of the late Japanese Minister of Marines in Tokio, when I was invited to see her little girl’s show of dolls.

O Haru San--the Honourable Miss Spring--who was an only child, and adored by her parents, greeted me with charming politeness and dignity, placing her tiny white hands on her knees and bowing her head down to the ground. She was a delightful little creature of eight years of age, very small and slender, with manners quite equal to the Countess, her mother, who is one of the most charming women I have met in the East. O Haru San was dressed in a fascinating gray silk crape kimono, with a fold of scarlet crape round the neck and a gold brocaded obi. Her face and throat were much whitened, the paint terminating in three points at the back of the neck; her lips were reddened and slightly touched with gold. Her hair was drawn back, raised in front and gathered into a double loop, into which a band of scarlet crape was twisted. On her feet she wore ‘tabi,’ little white linen socks hooked up at the side, with a separate place for the great toe, and I noticed her little lacquered ‘geta’ (clogs) were placed neatly together just outside the door. The whole effect reminded me of an exquisite wax model, and it was impossible to imagine that tiny delicate being capable of any mental or physical exertion.

To my surprise, however, she tripped gaily in front of me up the wooden staircase and down a long corridor to a large room where the Hina Matsuri was being held. She appeared perfectly at her ease, and chatted away, asking me many intelligent questions, through the interpreter, about little English girls, their games, dolls, etc.

On the landing a dolls’ garden was arranged, with small houses, bridges, miniature fir-trees--the latter a great speciality in Japan--a river with real water, even a minute pond with three gold-fish--the whole arrangement very artistically planned and set out. As O Haru San drew back the lacquered panels of her room, she looked at me anxiously to see how I should be impressed. I certainly had no cause to feign surprise. The sight was a most unusual one. The room was literally packed with dolls of every sort and description; almost every nationality was represented, some nearly life-size, others the length of one’s little finger; all were arranged in groups, standing, sitting, propped up against cushions, in every conceivable attitude.

On a kind of daïs were two dolls on thrones, representing the Emperor and Empress of Japan. As far as I could see every doll was in perfect order, every detail of their costumes correct--no broken noses, arms, or legs--no pins! Even in the hospital, where several pale-faced dolls were lying in bed, I noticed the splints and bandages were not to hide, but to represent, injuries.

My small hostess darted hither and thither, pointing out special favourites, rearranging some of the groups with her delicate little white hands with great care and precision. I thought of my favourite rag-doll Sally, with no features and destitute of legs, that I used to hug in my arms as a child when I went to sleep; and I wondered what O Haru San’s feelings would have been if I had suggested adding that mutilated remnant to her collection. What havoc a few English children would have made in that room! But a Japanese child is perfectly content to look and admire; and I imagine such a thing as breaking a doll would be considered almost a crime. Many of these toys, I was told, were over two hundred years old; some represented warriors and ‘samuri’ of the seventeenth century--uniforms, weapons, complete. I must not forget the dinner-service which was spread on one of the tables, and from which every day during the Matsuri food was served to the more important of the dolls by their young mistress.

How comic it all seemed, and yet how real and serious it was to little Miss Spring! She told me that at the end of the week every doll was carefully wrapped in paper and locked away until the following year, although one or two special favourites were occasionally brought out for change of air.

Before leaving O Haru San presented me with about a thimbleful of tea in a tiny transparent cup of white and gold, saying in her pretty little way: ‘This tea is worthless indeed, and green, but deign to moisten your honourable lips with it.’ I did as she requested, assuring her that never before had I tasted its equal in delicious fragrance.

One must be polite to avoid hopelessly disgracing one’s self in Japanese society.

I felt strongly inclined to kiss the tiny piquant face, white paint and all, as we said good-bye; but that would have been far too great a breach of etiquette to be tolerated by the little lady, who, bowing low as I left the house, begged ‘to be very kindly remembered to my most honourable father, of whom she had heard so much.’

The following extract, taken from a German book written in 1841, shows us how much importance has always been attached to the rules of politeness and etiquette in Japan. It says, speaking of education: ‘Children of the higher orders are carefully instructed in morals and manners, including the whole science of good-breeding, the minutest laws of etiquette, and the forms of behaviour as graduated towards every individual of the whole human race, by relation, rank, and station.’

Compulsory education exists all over the country, even in remote country villages in the interior. A drum beats at seven o’clock in the morning to summon the children to school, and if one is energetic enough to be about at that early hour, one sees troops of quaint little figures wending their way to the school-house with satchels on their backs, very possibly flying kites or spinning tops, according to the time of year, as they go along.

On a wet morning, instead of the merry little faces, nothing is visible but a long procession of large yellow parchment umbrellas, and bare brown legs and feet. With one hand the kimono is carefully held up high out of harm’s way, with no respect to appearances; in the other hand the children carry their ‘geta’ (clogs), which are only used in fine weather.

As Miss Bird says, describing a Japanese school:

‘The model behaviour of the children during school-hours is quite remarkable; they are so imbued with the spirit of obedience that their teachers have no difficulty in securing quiet and attention. In fact, they are almost too good; and their little old-fashioned faces look painfully serious sometimes as they pore over their books or repeat verses and lessons in their monotonous voices.’

One of their recitations, which I have since seen translated, ran as follows:

‘Colour and perfume vanish away;

What can be lasting in this world?

To-day disappears in the abyss of nothingness.

It is but the passing image of a dream, and causes only a slight trouble.’

In other words, ‘vanity of vanities’--a dismal ditty for young children, but very characteristic of the spirit of fatalism in the East.

‘The penalties for bad conduct used to be a few blows with a switch on the leg, or a slight burn with the “moxa” on the forefinger, but now the usual punishment is detention after school-hours.

‘The cost of education is not expensive--from a halfpenny to three halfpence a month, according to the means of the parent.’

Besides the national schools, there are many excellent colleges and schools for the children of the nobles and upper classes in Japan. In Tokio alone there are military, naval, and engineering colleges, besides a large University. Japanese students, however, frequently finish their education at foreign Universities, where they often take high degrees.

A girl generally leaves school when she is fifteen, but she continues her studies until she marries. An important part in her education is the arrangement of flowers, an art cultivated into a veritable science in Japan. I was anxious to take a few lessons, but was told that no satisfactory result could be obtained under three years’ constant study, so decided to leave that accomplishment to those who had more time and patience at their disposal.

I must not forget to mention some of the games and fêtes which take such an important place in the lives of Japanese children. I have described the Hina Matsuri, the festival for girls, which is celebrated on the 3rd of March. The feast for boys is held on the 5th of May at the festival of Hachman, the god of war. The towns and villages on that date present a most curious spectacle. Where there are any boys in the family, large, hollow, canvas kites in the form of a carp are hung at the end of long poles from every home; the number and size of the fish corresponding to the number and age of the boys in the family.

These fish used to be made large enough to carry a man up in the air, and have been known to be employed in time of war to spy into the interior of an enemy’s castle. On one occasion a robber was caught by means of their help, and killed, but they are no longer used for these practices.

The carp is chosen as an emblem at the feast of boys on account of its strength and power to swim up against stream. In like manner a boy is supposed to push his way along the stream of life and combat difficulties.

There is a very picturesque, and at the same time curiously pathetic, festival which takes place annually at the end of August at Nagasaki--the ‘Bon Matsuri,’ or festival to dead children. Every day during the week children in gorgeous costumes parade the streets of the town, carrying fans, banners and lanterns, collecting subscriptions. On the last day of the festival, at sunset, whole fleets of little straw sailing-boats, with food and a light on board each, are launched on the beach for the souls of the little children who have died.

How well I remember the scene! The sun was sinking like a ball of fire into the purple sea, tinging the mountains, the islands, and the yellow sand a delicate rose colour.

As far as the eye could reach numberless little figures were hurrying to and fro on the beach, fitting out their tiny crafts ready to launch into the water. As the sun sank behind the horizon the murmur of many voices broke the stillness, gradually resolving into a weird incantation, which echoed from hill to hill. This was the signal for the lighting and launching of the boats; a few minutes later, when night had fallen, the sea seemed ablaze with countless flickering lights; and on the shore, thousands of little figures, fast disappearing into the darkness, could be seen kneeling on the sand offering up their prayers and petitions for the welfare of the little ones they had lost, in whose memory the festival had been celebrated.

Since the opening up of the country to foreigners and the introduction of Western civilization, many of the quaint manners and customs in Japan are fast disappearing, and the Japanese children, especially in the Treaty-port towns, cannot be said to have benefited by the change.

Nothing can be more delightful than a Japanese child with Japanese manners; nothing, I grieve to say, more objectionable than one with European manners. Why is it, I wonder, that bad habits are so much more easily learnt than good ones?

In spite of all this, however, one must admit that much still remains, especially amongst the girls, of that grace, that gentle politeness and courtesy, which has ever given such a charm and attracted one so much to the children of Japonica.