CHAPTER VI.

“THE MASTER IS COME, AND CALLETH FOR THEE.”

RHODA seized upon her cousin as she was passing out of the tent. She was resolved that Helen should not go back to the dancing-room. What was done could not be undone. But she would take her away before the crowd had begun to disperse.

“Come, Helen,” she said, “I have your cloak and hat; you needn’t go into the house again. Mr. Gill will get the chaise ready at once.”

“O Rhoda, the fun is only just beginning,” pleaded Helen. “And I have promised to dance——”

“Then you must break the promise. It won’t be the first that you have broken to-night,” added Rhoda, sharply.

She wrapped Helen in her cloak, and tied her bonnet strings with her own hands. As they stood there, in the strange mingling of lamplight and moonlight, she could see that the lovely face looked half-frightened and half-mutinous. In an instant Rhoda repented of her momentary harshness; somehow she had never loved Helen better than she did at that instant.

“I’m sorry to spoil your pleasure, darling,” she whispered; “but what will the father say if we are late?”

Helen’s brow cleared. Without a word she walked straight to the place where the chaise was standing, and climbed up into her seat. William Gill, assisted by one of the squire’s stable helpers, proceeded to harness the chestnut horse, and in a few moments more they had driven out of the park.

It was such a relief to Rhoda to be going homewards, that for some moments she could think of nothing else. The cool night air soothed and refreshed her. The rattle of wheels and the quick tramp of hoofs were the only sounds that broke the silence. Cottages by the wayside were dark and still. The firs that bordered the road stood up rugged and black; not a tree-top rocked, not a branch rustled. The level highway was barred with deep shadows here and there. Overhead there was a soft, purple sky, and the moon hung like a globe of gold above the faintly outlined hills.

As they drew near the end of the three-mile drive, Rhoda’s troubled thoughts came flocking back. All Huntsdean and Dykeley would be talking of Helen Clarris to-morrow. Her dress, her jewels, her levity, would give the tongues of the gossips plenty of work for months to come. The Farrens were a proud family in their way. They were over-sensitive—as such people always are—and hated to be talked about. Rhoda knew that the village chatter could not fail to reach her father’s ears, and she knew, too, that it would vex him more than he would care to say. As Mrs. Gill had said, Helen had been strictly brought up. She had lived under her uncle’s roof in her childhood, and had gone to school with her cousin. All that had been done for Rhoda had been also done for her.

And then the jewels. Little as Miss Farren knew of the worth of such things, she had felt sure that they were of considerable value. Moreover, they were new and fashionable, and could not be mistaken for family heirlooms. Had Robert Clarris purchased them in his doting fondness for his wife? Were they love-gifts made soon after their marriage? Anyhow, Helen ought not to retain them. It was plainly her duty to dispose of them, and send the proceeds to Mr. Elton. Rhoda determined to speak to her about this matter on the morrow.

Just as she had formed this resolution, they turned out of the highway and entered the lane leading to Huntsdean. The road dipped suddenly; a sharp hill, overshadowed by trees, led into the village.

“Nearly home,” said Mrs. Gill, rousing herself from a doze. The words had hardly passed her lips, when the chestnut horse started forward with a mad bound. It might have been that William Gill’s brain was confused with the squire’s strong ale. A buckle had been carelessly fastened, and had given way. The horse’s flanks were scourged and stung by the flapping strap. There was a wild plunge into the darkness of the lane, a terrible swaying from side to side, and then a jerk and a crash at the bottom of the hill.

For a few seconds Rhoda lay half stunned upon the wet grass and bracken by the wayside. She rose with a calmness that afterwards seemed the strangest part of that night’s history. Mrs. Gill was sitting on the sod staring around her in a helpless way. The other two, William and Helen, were stretched motionless upon the stony road.

Still with that strange composure which never lasts long, Rhoda ran to the nearest cottage. Its windows were closed, and all was silent; but she beat hard upon the door with her clenched hands. A voice called to her from within, but she never ceased knocking until a labourer came forth.

“Hoskins,” she said, as the man confronted her, “my cousin has been thrown out of Farmer Gill’s chaise. You must come and carry her home.”

The man came with her to the foot of the hill, and lifted Helen in his strong arms. Other help was forthcoming. The labourer’s wife had roused her sons, and Mrs. Gill had collected her scattered senses.

They were but a quarter of a mile from home, but the distance seemed interminable to Rhoda as she sped on to the house. The familiar way appeared to lengthen as she ran; and when at last her hand touched the latch of the garden gate, her firmness suddenly broke down. She tottered as she reached the door, and then fell into John’s arms, crying out that Helen was coming.

The farmer sat in his large arm-chair. The Bible lay open on the table before him, for he had been gathering the old strength and sweetness from its pages. He had not guessed that the strength would so soon be needed. But it was his way to lay up stores for days of sorrow, and there was a look of quiet power in his face that helped those around him.

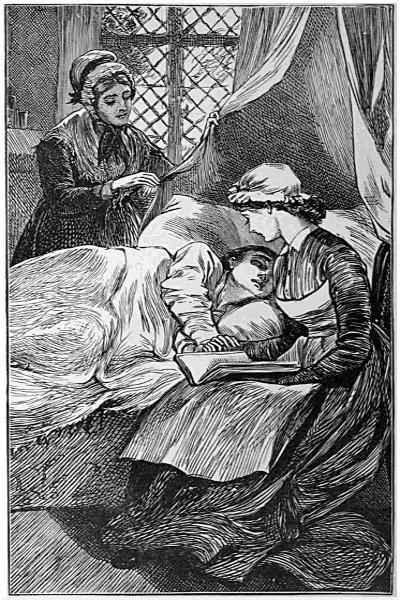

They carried Helen upstairs, and laid her on her bed. The lilac silk was dusty and blood-stained, the fragile lace soiled and torn. With tender hands Rhoda unclasped her glittering necklace and bracelets; the rings, too, slipped easily from the slight fingers. When those gay trinkets were out of sight, Rhoda’s heart was more at ease. Helen was their own Helen without them; the jewels had done their best to make her like a stranger. There was little to do then but to wait until the doctor arrived.

As it will be with the day of the Lord, so it often is with the day of trouble. It comes “as a snare.” Frequently, like the stag in the fable, we are looking for it in the very quarter from which it never proceeds. It steals upon us from another direction—suddenly, swiftly, “as a thief in the night.”

But the children of the kingdom are “not in darkness, that that day should overtake them as a thief.” They sleep, but their hearts wake; and there is light in their dwellings. Let the angels of death or of sorrow come when they will, they are ready to meet them. To the watchful and sober souls the Master’s messengers are never messengers of wrath. Ay, though they come with dark garments and veiled faces, they bring some token of Him who sends them. The garments “smell of myrrh, aloes, and cassia;” the glory of celestial love shines through the veil.

When Helen opened her eyes and looked round upon them all, they knew that there was death in her face. They knew it even before the doctor arrived, and told them the hard truth. She might linger a day or two perhaps, just long enough for a leave-taking, and then she must set forth on her lonely journey. But how were they to tell her that she must go?

“What did the doctor say?” she asked, faintly, after a long, long silence. The day was breaking then, but they were still gathered round her bed—still waiting and watching with that new, calm patience that is born of great sorrow.

“Nelly,” said the farmer, bending his head down to hers, “‘The Master is come, and calleth for thee.’ The call is sudden, my dear, very sudden. But it’s the Master’s voice that speaks.”

First there was a startled, distressed look, but it passed away like a cloud. The brown eyes were full of eager inquiry.

“Must it be?” she whispered. “Ah, I see it must! Oh, I’m not ready—not nearly ready. There’s so much to be forgiven; if I could only know that He forgives me, I wouldn’t want to stay.”

“Nelly!” answered the farmer in a clearer tone, “the Lord has got love and pardon for all those who want it. It’s only from those that don’t want it that He turns away. His blood has washed out the sins of that great multitude whom no man can number, and it will cleanse you too. Do you think He ever expects to find any of His children who don’t need washing? Ay, the darker they are in their own eyes, the fairer they seem in His!”

As Rhoda listened to her father’s words, and to her cousin’s low replies, she began to realize that poor, weak Helen had felt herself to be a sinner for many a day. She had felt it, and had tried to forget it. But this was not the first time that she had heard the Master’s call, and yearned to follow Him. Yet the weakness of the flesh had prevailed again and again, and her feet had gone on stumbling on the dark mountains. They would never stumble any more. The great King had come Himself to guide them over the golden pavement to the mansion prepared in His Father’s house.

All that day Rhoda’s mother was by the bedside. Rhoda herself went to and fro, now ministering to the baby’s wants, now hanging over her cousin’s pillow. Once she stayed out of the room for nearly half-an-hour, and on entering it again, she saw her mother strangely agitated. Helen’s head was on her aunt’s bosom, and her pale lips were moving. But Rhoda could not hear what she said.

“She tarried with them until the breaking of another day.”

She tarried with them until the breaking of another day. The sun came up. Shadows of jessamine sprays were drawn sharply on the white blind; a glory of golden light fell on the chamber wall. Towards that light the dying face was turned. To Rhoda, at that moment, came a sudden impulse. Clearly and firmly she repeated the familiar lines that she and Helen had learnt years ago,—

“The wide arms of Mercy are spread to enfold thee,

And sinners may hope, for the Sinless has died.”

For answer, there was a quick, bright smile, and then the half-breathed word—

“Forgiven.”

Only an hour later, Rhoda was walking along the grassy garden-path with Helen’s child in her arms. Was it yesterday that they were children playing together? Had ten years or sixty minutes gone by since she died? If she had come suddenly out of the old summer-house among the beeches—a gay, smiling girl—Rhoda could scarcely have wondered. There are moments in life when we put time away from us altogether.

And yet one had to come back to the everyday world again—a very fair world on that morning. Newly-reaped fields lay bare and glistening in the sun; thistle-down drifted about in the languid air, and the baby stretched out her hands to grasp the butterflies. She looked up, wonderingly, with Helen’s brown eyes, when Rhoda pressed her to her bosom and wept.