CHAPTER IV

A MIDNIGHT LUNCH.

“When you see me doing that, just tell me,” retorted Lafe, with another sneer.

“All right,” answered Bud, “I will.”

Surrounded by a wilderness of odds and ends, the youthful rivals stood and faced each other. Finally, Bud reached out his hand.

“What’s the use of scrappin’ Lafe? I guess we don’t like each other any too well, but we ought not let our grouch interfere with our chance.”

“What chance have you?” asked the bank clerk.

“Just a chance to get my hands on a real aeroplane. And that’s all I want. But I won’t have that if we don’t stop quarrelin’ and get to work.”

“Looks to me as if you thought I’d back out.”

“That’s up to you,” went on Bud. “I didn’t say so.”

“Are you willing to take orders and do as I say?”

“Sure,” answered Bud. “All I want is to see the thing fly. And, since you are the aviator, I say ‘Good luck to you.’”

Lafe had ignored the proffered hand, but he now relented a little.

“I want to be fair,” he said half-heartedly, “and I’ll meet you half way. But I don’t intend to work all night to give you a chance to show off to-morrow.”

“Never fear,” answered Bud. “I had hopes for a minute, but they were like all my other chances.” And he whistled. “You’re it and I’m nit. Come on, let’s forget our troubles.”

As he smiled and held out his hand again, Lafe had not the heart to refuse it.

“Now,” went on Bud enthusiastically as the two lads limply clasped hands, “we’re on the job. What’s doin’?”

Within a few minutes, the rivalry was forgotten, at least temporarily. The only headway made so far was in the mounting or setting up of a few sections of the frame. More than half of the work was yet to be done; the front and rear rudders were to be attached and levers adjusted; the vulcanized silk covering of the two planes had to be put in place and stretched; the landing skids bolted on; the engine, gasoline tank, and water cooler put in place and tested; the batteries wired; the propellers and shafts located; the chain gears and guards attached, and, possibly most important, the starting rail and weight derrick constructed. And it was then nine o’clock.

“Let’s get started right,” suggested Bud, “now that you have everything unpacked. Before we go any further let’s see where we stand.”

As a result of a nearly thirty-minute conference, these were the conclusions: A mechanic must be found at once, if possible, to adjust the engine, oil it and get it running; a carpenter must also be secured to start to work by midnight on the starting track; these things arranged for, the two amateurs agreed that, together, they could have the aeroplane itself so far set up by daylight as to give assurance to the fair directors that the day’s program could be carried out.

“And then,” suggested Lafe, “I suppose T. Glenn Dare will sail in on the noon train and steal our thunder.”

“He can’t steal mine,” laughed Bud. “I’ll have been through this thing by that time from top to bottom. That’s all I want—that, I can get,” he added with another laugh.

The first stumbling block was the launching device. This essential part of any aeroplane flight is usually a single wooden rail about eight inches high, faced with strap iron. As it is necessary with most modern aeroplanes to make a run before sufficient sustention is secured to force the machine into the air, it is evident that this starting impulse must be secured through an outside force.

The specifications forwarded with the airship purchased by the fair authorities, called for the long wooden rail. On this the aeroplane was to be balanced on a small two-wheeled truck. At the rear end of the rail, the plans called for a small derrick, pyramidal in form, constructed of four timbers each twenty-five feet long and two inches square braced by horizontal frames and wire stays.

At the top and at the bottom of this, were two, pulley blocks with a rope passing around the sheaves a sufficient number of times to provide a three-to-one relation between a 1500-pound weight suspended from the top pulley and the movement of the aeroplane on the track.

The rope, which passes around the pulley at the bottom of the derrick, is carried forward to and around a pulley at the front end of the rail, and thence back to the aeroplane, to which it is attached with a right-angled hook. When everything is ready for an ascension and the operator is in place, the propellers are set to work. When they have reached their maximum revolution and the car begins to feel their propelling force, the weight, usually several bags of sand, is released, the tightened rope shoots through the pulleys and the balanced aeroplane springs forward on its car. By the time it has traveled seventy-five or one hundred feet, the impulse of the falling weight and the lift of the propellers sends it soaring. Thereupon, the hook drops off and the free airship begins its flight.

“We have the plans for the derrick and the track, the pulley blocks, rope and hook,” declared Bud at once. “But we haven’t the little car.”

“Couldn’t we make one?” ventured Lafe.

“Certainly, but hardly in the time we have.”

“I’ve heard of aeroplanes ascending by skidding along over the grass,” suggested the bank clerk.

“But they weren’t in the hands of amateurs. We’d better stick to the rail. I’ve been thinking over this—down there in the freight-house.”

“Did you know the track car wasn’t here?”

“Well, I didn’t see it. Here is the idea. The aeroplane has two light, smooth landing runners or skids. Lumber is cheap. Instead of a track for the wheels we haven’t got, we’ll make two grooves just as long as the proposed track. We’ll stake these out on the ground and set the landing runners in them after we’ve greased the grooves with tallow. The weight, rope and hook will work exactly as if we had a single track—’n possibly better. Anything the matter with that suggestion?”

Lafe was skeptical a few moments while Bud made a sketch of the new device. Then he conceded that he could see no reason why it wouldn’t work.

“All right,” exclaimed Bud, in a businesslike way, “now, you go ahead, and I’m off for town for the timber and the men we need. You can’t do much single handed, of course, but do what you can. I’ll be back before midnight. Then we’ll get down to business.”

The boy had no vehicle to carry him the two miles to Scottsville, so he walked. The night was dark, and almost starless, and the pike or road was soft with heavy dust; but, with his coat on his arm, Bud struck out with the stride of a Weston. Covered with dust and perspiration, in about half an hour, he reached the edge of the town. Entering the first open place he found, a sort of neighborhood grocery, he called up Mr. Elder by telephone.

It required some minutes to fully explain the situation, but finally he convinced the fair official that the things he suggested were absolutely necessary and must be done at once. As a result, by the time Bud reached the town public square, Mr. Elder was waiting for him in the office of the hotel.

The usual “fair week” theatrical entertainment was in progress in the town “opera-house,” fakers were orating beneath their street torches, and the square was alive with Scottsville citizens and those already arrived for the fair. It was not difficult for President Elder to start things moving. Within a half hour he had found, and for extra pay, arranged for two carpenters and an engineer to report at the fair-grounds at once.

The securing of the lumber was not so easy and called for some persistent telephoning. Finally an employe of the “Hoosier Sash, Door and Blind Co.” was found, and he in turn secured a teamster. At ten-thirty o’clock, Bud was in the lumber yard selecting the needed material with the aid of a smoky lantern, and before eleven o’clock the one-horse wagon was on its way to the fair-grounds. The two carpenters reached the airship shed about eleven-thirty in a spring wagon with their tools, and a little after twelve o’clock the engineer arrived on foot with a hammer, a wrench and a punch in his pocket.

Before work really began, Bud startled Pennington with a cheery question.

“Say, Lafe, I’m hungry as a chicken, and I’ve only got a dime. Got any money?”

Lafe was not celebrated for generosity.

“I don’t see what good money’ll do out here. There’s no place to buy stuff. And it’s midnight anyway.”

“If you’ll produce, I’ll get something to eat,” said Bud with a grin.

“Here’s a quarter,” answered Pennington slowly.

“Gimme a dollar,” exclaimed Bud. “I’ll pay it back. I forgot to speak of it to Mr. Elder.”

“What do you want with a dollar?” asked his associate, somewhat alarmed. Bud’s credit wasn’t the sort that would ordinarily warrant such a loan.

“Why, for all of us, of course. We can’t work all night on empty stomachs. And there’s five of us.”

Thereupon, Lafe rose to the occasion and handed Bud a two-dollar bill.

“You can bring me the change,” he suggested promptly. “I’ll charge it up to the fair officers.”

Bud was off in the dark. His hopes of securing something to eat were based on what he had seen passing through the grounds on his way back with the lumber. In several groups under the big trees, he had seen camp-fires. “Concession” owners and their attendants who remained on the grounds during the night had turned the vicinity of the silent tents and booths into a lively camp. In one place, the proprietor of a “red hot” stand had a bed of charcoal glowing, and a supply of toasting sausages on the grill. These were in apparently steady demand by watchmen, hostlers, live stock owners and many others who had not yet retired.

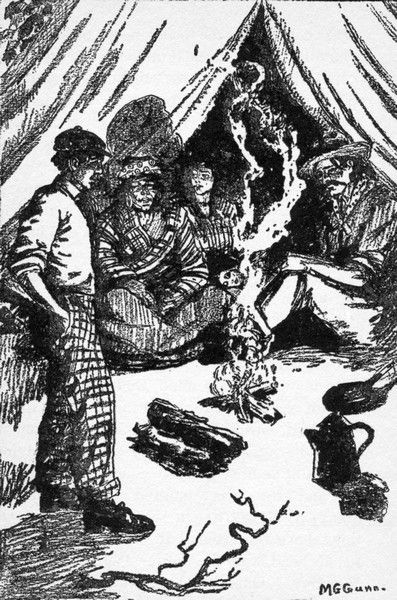

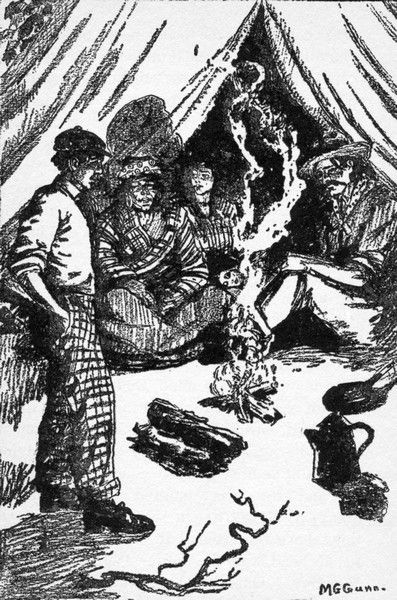

On his way to this stand, Bud passed what he had not observed before. In the rear of a dirty, small tent, an old woman, a man and a woman of middle age were squatted about the dying embers of a fire. Almost concealing both the tent and group was a painted picture, worn and dingy, displayed like a side-show canvas. On this, above the attempt to outline an Egyptian female head, were the words: “Madame Zecatacas, Gypsy Queen. The Future Revealed.”

BUD BARGAINS FOR COFFEE.

Bud could not resist the temptation to stop a moment. The man greeted him with a stare, but the old woman held out a skinny hand. Her brown, wrinkled face was almost repulsive. A red and yellow handkerchief was wound around her head, and her oily, thin black hair was twisted into tight braids behind her ears, from which hung long, brassy-looking earrings. In spite of her age, she was neither bent nor feeble.

As the low fire played on the gaudy colors of her thick dress, she leaned forward, her hand still extended.

“Twelve o’clock, the good-luck hour,” she exclaimed in a broken voice. “I see good fortune in store for the young gentleman. Let the Gypsy Queen read your fate. Cross Zecatacas’ palm with silver. I see good fortune for the young gentleman.”

There was something uncanny in the surroundings, and Bud was about to beat a retreat, when the man exclaimed:

“Got a cigarette, Kid?”

In explaining that he had not, Bud’s eyes fell on the rest of the group. A little girl lay asleep with her head in the middle-aged woman’s lap. The man held a tin cup in his hand. On the coals of the fire stood a coffee pot.

“Got some coffee, there?” asked Bud abruptly.

The man grunted in the negative. The old woman punched the coals into a blaze.

“Give you fifty cents, if you’ll make me a pot full,” said Bud.

The little girl’s mother looked up with interest.

“What kind o’ money?” drawled the man.

“Part of this,” said Bud displaying Lafe’s two-dollar bill.

The man reached out his hand.

“Got the change?” Bud inquired.

The old woman reached under her dress and withdrew her hand with a bag of silver coin.

“We’re over in the track working on the airship,” explained Bud with no little pride. “When it’s ready bring it over. You can see the aeroplane.”

In the matter of food, Bud secured not only “red hots,” sandwiches and dill pickles, but a few cheese and ham sandwiches. Altogether he expended a dollar and twenty-five cents of Lafe’s money.

“Here you are,” he exclaimed on his return, while the new workmen grinned and chuckled, “hot dogs and ham on the bun. Coffee’ll be here in a few minutes.”