CHAPTER XIII

A UNIQUE STARTING DEVICE.

“Anyway,” exclaimed Bud, after he had returned with his supplies and made another examination of the aeroplane, “the engine is in good shape. The landing skids kept it above the weeds and it’s as dry as a bone.”

Half naked, the boy went to work on the airship, and, with no little annoyance from mosquitoes and sunburn, he soon had the broken cross-piece mended.

Meanwhile, the two mill hands had managed to secure a couple of substantial fence planks, each about ten feet long. While Bud tested each brace in the car—fortunately the front and rear rudders and the two propellers escaped without a scratch—Mr. Camp and his hands beat down the tangle of cattails and flags. By using the fence boards to walk on, a temporary tramway was made and when the busy young aviator was ready to move his car, the planks were laid ready for the first ten-foot lift.

“Now then,” called out Mr. Camp, as the three men and Bud took their places, “right up to yer shoulder and then all together.”

With Mr. Camp and Bud in front and the others just behind them—all standing on the narrow boards—they slowly raised the frame into the air. At the end of the improvised walk, the car was gently eased to the beaten-down weeds and the boards were shoved forward. Again, the aeroplane was lifted and carried another ten feet. The next lift would bring the frame to the water’s edge.

Before this was made, Bud lined up the two boats about fifteen feet apart and anchored them between oars and sticks stuck in the mud. Then, every one removing his shoes and trousers, the airship squad got its shoulders under the machine once more, and, splashing and slipping in the shallow water and mud, carefully laid the aeroplane on the boats.

“This is all new business to me,” said Mr. Camp, slapping at the mosquitoes, thick on his unprotected legs, “but I’m ketchin’ on. An’ I got an idee a’ready,” he added knowingly. “I see what you’re figgerin’ on, Bud. Ef ye git back here to-night, don’t land on the marsh. Ef ye’ll jest make a landin’ over yender on the slope o’ the hill ye can git out o’ all this trouble.”

“But I’d have as much trouble gettin’ the car over to the flume to raise it again,” suggested Bud.

“That’s where you’re mistaken, an’ that’s where my idee comes in. I reckon ye kin start in the flume, but that’s fur frum bein’ the easiest way.”

“What would you do?” asked Bud, with rather a patronizing smile.

“Well, as I figger it out,” said Mr. Camp, parting his flowing beard to expectorate, “all ye want is a run fur yer money. There’s more ways o’ gettin’ a runnin’ start than on a boat. When you git back to-night, I’ll have an old spring wagon I got up thar nigh the top o’ the hill. An’ I’ll have her greased good an’ plenty. Tomorrer we’ll put the flying-machine on the wagon an’ Josh in the shafts. When he gits goin’ down hill ef he don’t beat this ole flat-boat I’m a liar.”

“Mr. Camp,” laughed Bud, approvingly, “if it wasn’t for gettin’ the aeroplane over the marsh and on the hill, I’d try it to-day. That’s a bird of a way.”

“Oh, I’m purty handy that away,” remarked the mill owner in a satisfied tone.

Mr. Camp and one of the men climbed into the boats to balance the long frame, while the other man and Bud, keeping within wading distance of the shore, began the task of pushing the boats the quarter of a mile or more to the dam. Before they reached the lower end of the pond, Josh could be seen making his way laboriously up the plank walk along the flume, pushing a wheelbarrow loaded with the wood-encased can of gasoline.

It was nearly noon, and, by the time the aeroplane had been lifted from its floating foundation and deposited safely upon the clay dam or levee, the distant but welcome sound of Mr. Camp’s dinner bell could be heard.

“There don’t seem to be any risk in leaving it here,” suggested Bud. “There isn’t a living thing in sight except birds. And, anyway, I’ve got to get my clothes, to say nothing of that chicken potpie.”

“I don’t know about that,” said Josh doubtfully. “Mebbe I better stay. They been a telephonin’ ever’ where ’bout a lost flyin’ machine. Somebody called up the store in Little Town this mornin’ while I was there, astin’ ef any one had heerd o’ a lost flyin’ machine.”

Bud showed some alarm.

“Don’t be skeered, son,” exclaimed Mr. Camp. “Thet ain’t because they think it’s up this way. They probable been telephonin’ all over the county.”

It was finally agreed that Josh should remain on guard, and that his dinner should be brought to him. After getting into their clothes, the others started for the house. On the way, Bud was in a deep study. He had no concern about his return to the fair-ground and no fear but what he would give a successful exhibition, but what was to follow? Certainly Attorney Stockwell and Mr. Dare and the deputy sheriff would be on the watch for him.

And, if they were looking out for the stolen aeroplane, they would not only see it approaching, but they would see the direction it took on leaving. On a fast horse, a man might almost keep close enough on the track of the retreating car to see it come down. After that, it might be only a question of a few hours search. You can’t well hide a forty-foot wide expanse of white canvas.

“Mr. Camp,” said Bud, at last, as they hurried along over the wood road, “you figured out that starting apparatus so well, maybe you can help me out of some other trouble.”

He related his predicament as he saw it. The old man wagged his jaws and stroked his long whiskers.

“Gimme a little time,” he replied at last. “That’s a purty tough problem, but mebbe I kin git some answer to it.”

At the house, it was like a holiday.

“Seems jes like Sunday with the mill shet down,” remarked Mrs. Camp, opening a can of pickled pears. “You all git ready right away. Dinner’s all dryin’ up.”

Bud changed his clothes—Mrs. Camp had even pressed his pants—and the four men soused and scrubbed themselves, and all took turns with the hanging comb. Then they filed in to dinner. It wasn’t a question of light or dark meat of the chicken with Mr. Camp when he served the pot-pie. The half spoon and half dipper plunged into the smoking soup tureen came up charged with gravy, dumplings and meat. Into the center of this, went the mashed potatoes, with butter melting on top of the pile.

In the midst of the dinner, Mr. Camp suddenly balanced his knife on his hand, struck the table with the butt of his fork and exclaimed:

“I’ve got her, Bud.”

“Got what, Pa?” broke in Mrs. Camp, nervously, as she sprang up and looked into the pot-pie bowl.

Her husband smiled, pounded the table again, and went on:

“Sure as shootin’, Bud, them fellers is agoin’ to foller you. Mebbe you could go right back there to the lake an’ never be discivered, and mebbe not. ’Tain’t no use takin’ chances. Jest you hold yer horses, finish yer pie, an’ I’ll put a bug in yer ear.”

“You’ve got a way to hide me?” exclaimed Bud eagerly.

“I hev that. An’ it’s simple as A. B. C.”

With most profuse thanks to Mrs. Camp for all she had done for him and many promises to come and see her later if anything prevented his return that night, Bud took farewell of his hostess. The men had already left with Josh’s dinner. Out in the open space between the dooryard and the mill, Mr. Camp, helping himself to an ample supply of Kentucky twist, explained to Bud the details of his plan for concealing the aeroplane that night. It did not have to be told twice. The exuberant boy chuckled with delight.

“Mr. Camp,” exclaimed Bud, “if I ever get my farm, I’m goin’ to buy an aeroplane. It’s goin’ to be a two-seater, too. An’ the first passenger ’at rides with me’ll be you.”

“Well, sir,” replied the farmer mill owner, twisting a lock of his whiskers about his horny finger and shaking his head, “don’t you worry about me bein’ afeered.”

It wasn’t an hour after the working squad reached the dam and head gates again until the aeroplane was ready for flight. The gasoline tank was full, the oil cups were charged and the engine—to the joy of Mr. Camp and his hands—had been tested and found in order. The flat boat had been lifted over the head-gate and was on the flume ready to dart away upon the rushing flood of water when the head-gate was raised. Finally, the bird-like framework had been balanced on the thwarts of the flat boat, and nothing remain but to wait for the time to start.

It was then a quarter after two o’clock. Nearly a half hour remained before leaving time. In spite of the plan proposed by Mr. Camp, Bud, it was further suggested, ought to lose no opportunity to mislead his almost certain pursuers. This meant that he should arrange his flight from the fair-grounds so that he would head west. That would take him away from Scottsville and toward a bit of low ground about four miles west of the fair-ground. Both sides of this were heavily timbered.

“Ef ye kin git down thar in the ‘slashins’ afore they git too clost to ye,” explained Mr. Camp, “an’ it ain’t too dangersome to git clost to the groun’, ye kin make a quick turn an’ shoot along in the valley till ye come to the ole Little Town road. An’ that’ll take ye furder in the hills. Like as not ye kin git clean away unbeknownst to ’em.”

“I’ll try it,” exclaimed Bud. “But I reckon it don’t matter much. We got ’em cinched if I ever get back here. And I’ll be here about a quarter to four,” he added.

Mr. Camp’s plan did credit to the old man’s ingenuity. This is how he explained it to Bud:

“Ye see the saw house down there?” he began. “Well, sir, ’at’s fifty feet long, or more. An’ ye see that track? They’s a car ’at runs on that to haul the logs into the shed to be sawed. When ye git back, ye’ll come right here and land afore the mill. Me an’ Josh an’ the hands’ll be waitin’ an’ the log car’ll be all ready. Afore ye kin say Jack Robison, we’ll have thet flying-machine on the log car an’ in the shed.”

“And the doors closed,” added Bud enthusiastically.

“Not by no means. That would be suspicious like ’cause they ain’t never shet. This afternoon, they’ll be two pulleys rigged up in the comb o’ the shed all ready to yank the flyin’-machine up agin the roof—clear o’ the car.”

“But they’ll see it!”

“They’ll be some pieces o’ timber all sawed to run acrost under the machine like as if it was a kind of a second floor. An’ they’ll be plenty o’ loose boards all stacked to lay on them jice. I been kind o’ needin’ a attic there any way,” laughed the grizzled mill owner. “An’ ef them jice is old timber an’ the floor is old boards, I reckon ain’t no one goin’ to suspicion it’s all been made suddent like. An’ it don’t ’pear to me any one’s goin’ to take the trouble to look up in the attic fur no airplane.”

It was at this point that Bud had chuckled. Then his enthusiasm cooled.

“How about getting another start?” he asked suddenly.

Mr. Camp chuckled in turn.

“Didn’t I tell you about the hill and the spring wagon and Josh for a engine?”

“And we’ll carry it over there?”

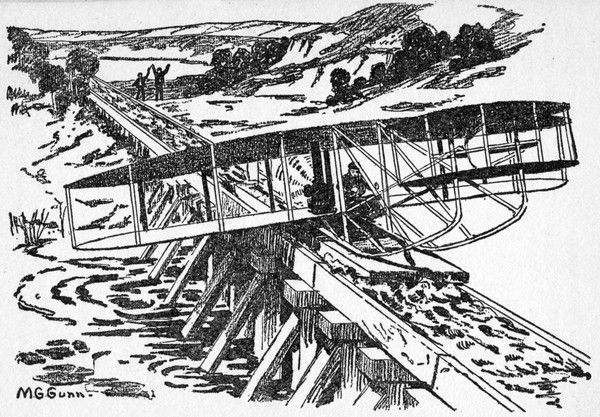

THE START FROM THE FLUME.

“The log wagon can be made thirty feet long,” drawled Mr. Camp with another laugh. “We’ll haul it there like one o’ them poles they raise at the rallies.”

As these details were gone over again, the old mill owner kept a close eye on his thick silver watch. At twenty-five minutes of three, he arose with the importance of Dewey at Manila.

“Well, Bud,” he exclaimed, extending his gnarled hand—his jaws working vigorously, as they always did in moments of excitement, “time’s up. An’ good luck to ye.”

It was an exhilarating moment for Bud. Stationing Josh and one of the men at either end of the balanced airship, he knocked the block from under the front of the flat boat, while the other mill hands held the stern of the boat. Then, tightening his hat, Bud took his seat, and rapidly tested all levers.

“Hold on, boys,” he said soberly, “until I yell ‘Go.’”

“Air ye all ready?” exclaimed Mr. Camp standing over the head-gate with the lever that swung it up in his hand.

Bud turned in his seat, set the engine going, and then watched the propellers begin to whirl. As their speed increased and the car began to tremble, he said in a low voice to Mr. Camp:

“Turn her on!”

As the heavy-muscled man threw himself upon the lever and the gates slowly rose, the banked up water rolled out beneath them like a wave of oil. As the released flood shot under the car, Bud was firm in his seat, both hands on the levers. There was a bob of the flat boat upward, and the boy shouted, “Go!”

For a moment only, the boat seemed to pause like a chip on the brink of an angry waterfall, and then, carried upon the crest of the new torrent, it shot forward like a rock falling. There was time only for a few swift blows on the sides of the flume, and then the aeroplane, rising from the impetus of its unique flight, leaped forward and began to rise. Bud did not turn, but he waved his hand in jubilation. The airship was safely afloat.