CHAPTER X

THE GREASED PIG

I was put into the car with Scoop, the policeman taking a seat between us, after which the driver turned the car around and started back down the street.

I was scared. I can’t deny it. However undeserving I was of arrest, the fact remained that I had been picked up by the law. And innocent though I was, it might not be easy for me to prove my innocence and thereby gain my freedom.

The automobile stopped in front of the mayor’s office and the policeman gruffly ordered us to pile out.

“If you try to run away,” he scowled, “I’ll catch you an’ give you ten years at hard labor.”

That, of course, was a bluff, and I knew it. For I was well enough acquainted with the processes of the law to know that it was a policeman’s job to capture law breakers and not to sentence them.

Still, I didn’t like to have him talk that way. It gave me a sort of trapped, helpless feeling.

We all went into the mayor’s office, the policeman and my chum and I in one group and the car’s other four occupants in another group.

The Strickers were in their glory. Walking on my heels, sort of, Bid kept saying under his breath: “How do you like it, Jerry? Whose turn is it now? You will scare us with your old ghost trick, hey?”

I didn’t say anything back. For what was the use? However, I did a lot of thinking. And, in mentally comparing myself with my tormentor, I told myself that I would rather be a jailbird all the rest of my life than to have his mean disposition. Much as I dislike the Zulutown gang, of which Bid is the leader (and I have good occasion to dislike them, let me tell you), I don’t go out of my way to pester them. Nor do any of my chums, for that matter. But when we do something that gains for us added fun or special public attention, it seems to gall Bid and his gang to the point where all they care to think about is how they can torment us.

The mayor wasn’t behind his desk, so the policeman told the driver, a lanky, hungry-looking fellow, to go out and find him.

“Put your handbills over there,” the officer told us, pointing to a table beside the room’s big desk. His scowl deepened as we obeyed him. “It’s plain,” he added, “that you kids don’t know much about the ordinances of this here town.”

I was less frightened now. For I had come to realize all in an instant how easily I could get in touch with Dad if necessary. He would come in a hurry if I telephoned to him that I was in trouble. And he’d know just what to do to gain my release.

“What’s the idea of arresting us?” Scoop spoke up. “We haven’t done anything wrong.”

“Is that so?” Bid put in, letting out his neck. “My Uncle Ike, I want to tell you, is the town bill poster—”

“Shut up!” thundered the policeman. “I’ll do the talkin’.”

Scoop and I exchanged glances.

“Is it against the law,” my chum inquired, getting a clue to the cause of our arrest from what Bid had blurted out, “to peddle bills in this town?”

“You bet your boots it is,” Bid waggled. “For the council gave my Uncle Ike the right——”

“Shut up!” bellowed the policeman a second time. “If I have to tell you ag’in,” he threatened, acting as though he was talking across the continent to some one in New York City, “I’ll throw you out.” He turned to us. “We don’t ’low every Tom, Dick an’ Harry to throw bills ’round our town to litter up our streets. Not by a jugful! We’ve got a town bill poster an’ it’s his job to ’tend to distributin’ handbills an’ puttin’ up posters. That was him I just sent after the mayor.”

Well, it was a relief to us to know that we weren’t charged with anything more unlawful than peddling handbills without a permit.

“Gee!” grinned Scoop, shedding his depression. “We thought you had us spotted for a pair of escaped bank robbers.”

“Here comes the mayor,” the policeman growled. “He’ll ’tend to your young hides.”

The summoned executive came briskly into the room, followed closely by the hungry-looker.

“What’s the trouble, boys?” our friend inquired.

“The trouble is,” spoke up the policeman in his long-distance voice, “that they’ve bin peddlin’ bills without a permit. Ike here caught ’em at it an’ called on me to make the arrest.”

“They hain’t got no right to go peddlin’ handbills in this here teown,” Ike put in, wagging and working his mouth as though he wanted to spit and didn’t have a place. We learned afterwards that he was an uncle of the Strickers’. “The council made me official bill poster,” he added, with more wagging, “an’ if they’s any bills to be put out in this here teown, I’m a-goin’ to do it, by heck!”

The mayor gravely inquired if we had been handing out bills. In his admission, Scoop pointed to the handbills on the table. The executive picked up one of the bills and read it.

“I’m sorry, boys, but Ike has a case against you. We have an ordinance that prohibits the distribution of circulars such as this except through our authorized bill poster. I’ll have to register a complaint against you for disturbing the peace and fine you. The fine will be one dollar each and costs. I have the right to withdraw the costs, and I’m going to do that.”

I had told Scoop about my “emergency” ten-dollar bill. We had laughed about it at the time, saying to each other that we would have no occasion to use it. Now, as I fished the greenback out of my pocket, I gave my companion a sort of sheepish grin.

I was given eight dollars in change.

“Remember,” the executive enjoined, holding my eyes, “you’re to do no more bill peddling. If you want the rest of your bills peddled, you’ll have to make arrangements with Ike.”

The hungry one put out his neck, an eager look in his eyes.

“I’ll peddle ’em fur a dollar,” he offered, working his mouth.

“No, you won’t,” Scoop snapped, scowling. “We wouldn’t give you a penny if we never had a bill peddled.”

“Haw! haw! haw!” hooted Bid Stricker, acting big in his triumph over us. “Listen to him blow.”

“You’re going to get your pay for this,” cried Scoop, shaking his fist at the enemy.

“Tut! tut!” the mayor put in quickly. “I won’t allow you boys to quarrel in here.”

“Can we go now?” Scoop inquired shortly.

“Certainly.”

“Hey!” screeched Ike, as we started for the door. “They’re takin’ the handbills with ’em.”

The mayor gave the screecher a sort of disgusted look.

“Why shouldn’t they? The handbills are theirs.”

“Yes,” whined Ike, more hungry-looking than ever, “an’ they’ll go peddlin’ ’em out on the sly.”

The mayor followed us to the door, his hands on our shoulders.

“Forget about it, boys. As I say, I’m sorry that it happened; but, of course, as long as we have this ordinance I must stand by it.”

When we came to the dock we had to pick our way through a knot of kids. Red was yelling through the megaphone, telling the curious ones what a wonderful show awaited them. But the spieler quickly put away his megaphone at sight of our angry faces.

“Tee! hee!” he snickered, when he had been told about our arrest. “I wish I could have seen you in the coop. I bet you made a swell pair of jailbirds.”

“Laugh all you want to,” growled Scoop, “but the Strickers are going to get their pay for this. We didn’t do anything to them when they tried to destroy our stuff. And we didn’t go after them when they stretched the rope across the canal. But this time they’re going to catch it.”

We kept the organ grinding away all of the afternoon. The kids enjoyed it. We kept telling them that they would miss the treat of their lives if they passed up seeing the Great Kermann.

Stopping the organ at five-thirty to get supper, we started it again at seven o’clock. Quite a crowd turned out by eight-thirty. When we gave our show, every seat was taken. The mayor was there with three kids. The fellow with the hungry face separated himself from fifteen cents and decorated one of the seats. Red told us afterwards that the policeman tried to get in for nothing, but was told to “go chase himself.”

Scoop went through with his tricks without a hitch. Peg and I had a lot of fun helping him. I didn’t spoil the “Living Head” trick by yelling, as I had done at our first show in Tutter.

Red sold sixteen fifteen-cent tickets and thirty-six ten-cent tickets, a matter of six dollars.

We were happy in our success; and in talking about it back and forth it was quickly decided that we should go directly to Steam Corners, instead of camping on Oak Island. If everything was well with our boat at the conclusion of our next show, we would long-distance our folks, begging permission to go farther from home with our show, into the territory beyond Steam Corners. It would be vastly more fun giving shows and earning money than camping. And if we did want to camp for a few days, we could stop at Oak Island on our triumphant return home.

It was our plan to pull out as soon as the show was over; but before leaving Ashton Scoop and Peg got their heads together and started off into the darkness. They said they were going shopping, to buy some bread and butter. But from their actions I knew that they had another purpose in mind in leaving the boat.

Were they intending to corner the enemy in some dark alley and pass out a few effective black-eye punches? I went worried in the thought of it. Not that I was afraid of the Strickers—far from it. It was the thought of being jailed again, for fighting, that troubled me. We had the mayor’s friendship. And I didn’t want to lose that friendship by appearing a second time before him as a law breaker.

So it was a big relief to me when I caught the sound of my returning companions’ laughing voices. There was another sound, too, that I couldn’t place. A sort of gurgling, grunting sound.

I almost fell over in my surprise when the avengers appeared dragging a half-grown pig.

“What the dickens?…” I cried, staring.

“It’s a present for the Strickers and Uncle Ike,” grinned Scoop, panting from his hard work of lugging the big pig.

“What do you mean?” I cried.

The newcomers looked at each other and laughed.

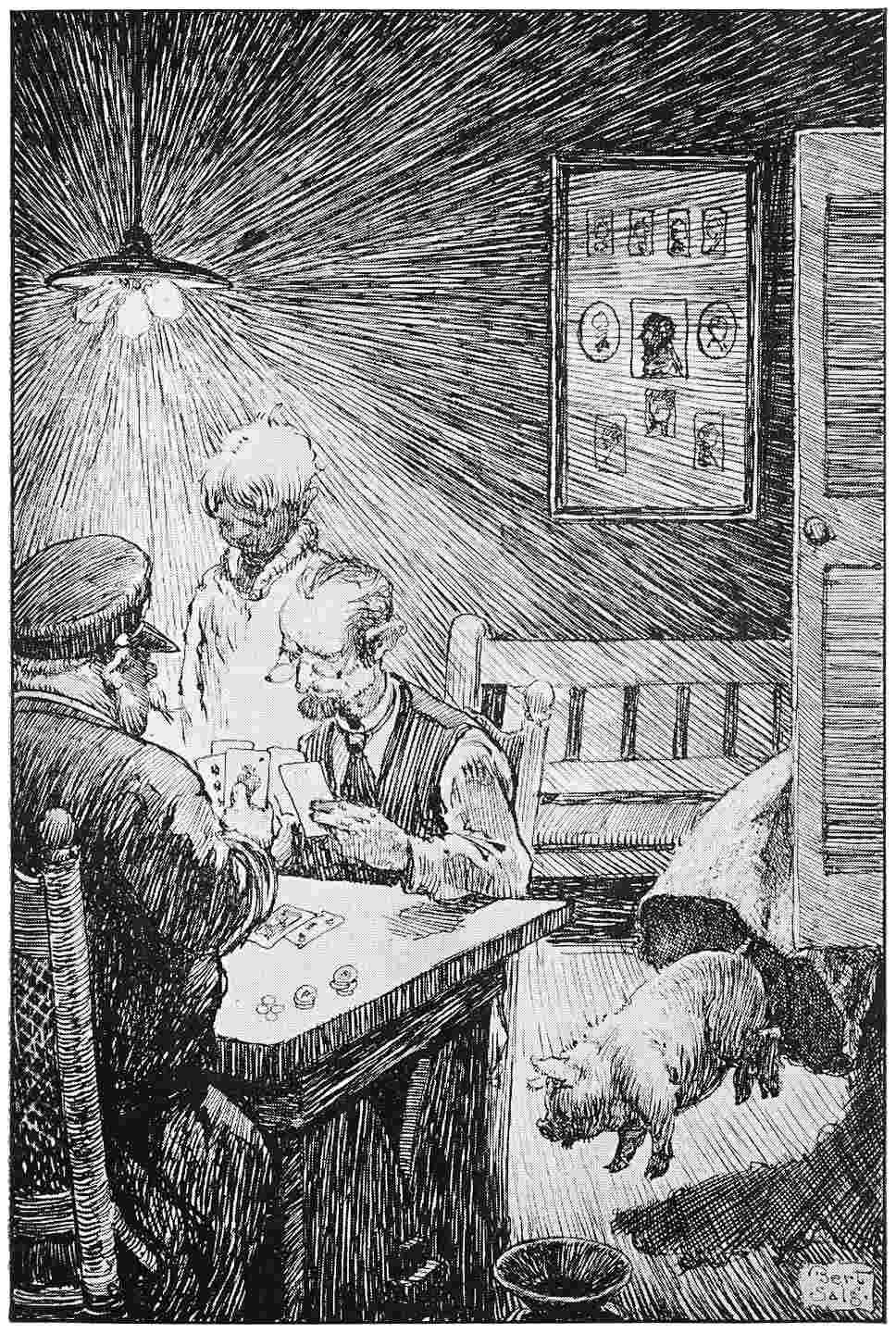

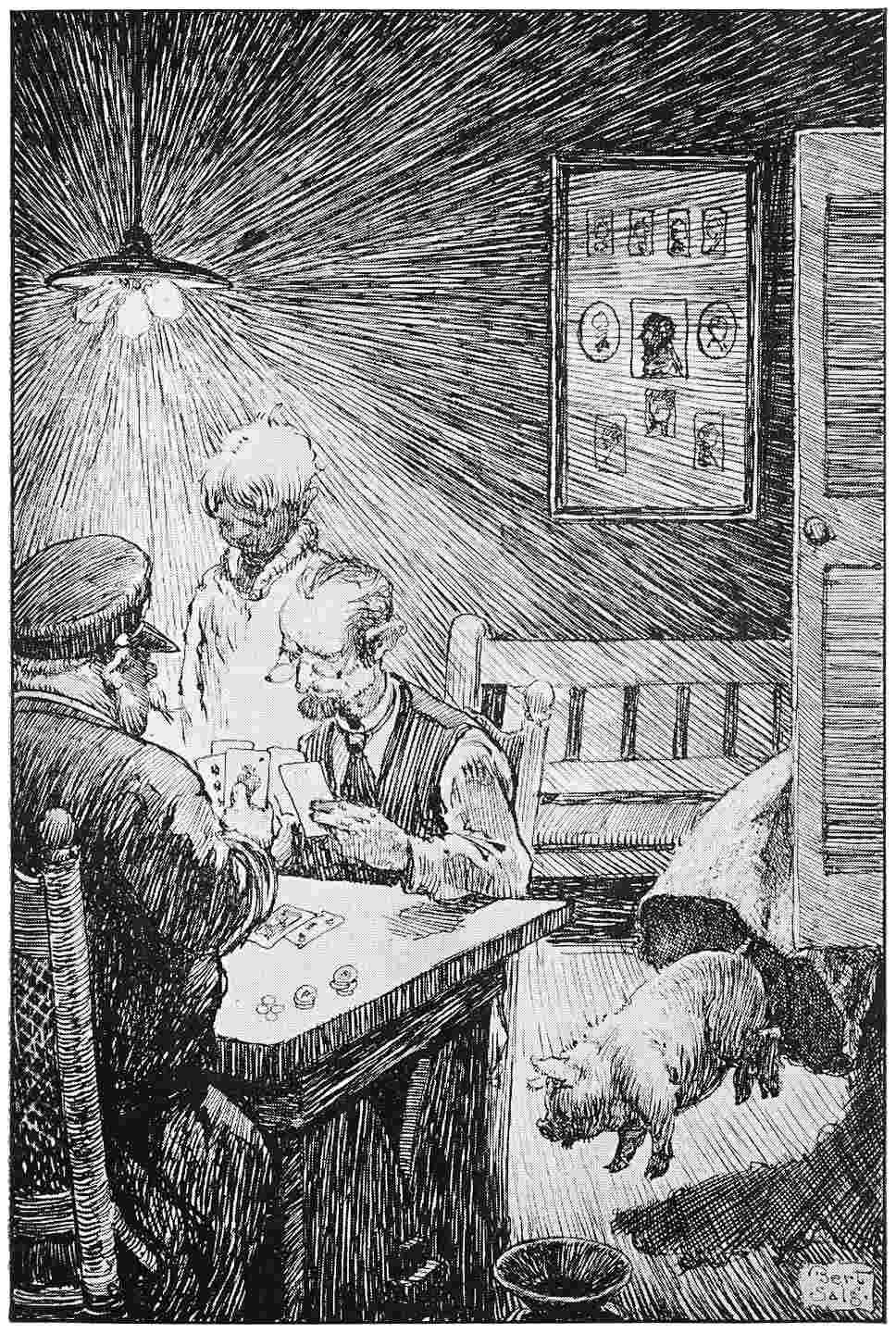

“We’ve got a peachy scheme, Jerry. We found the pig snooping about in an alley and we’re going to take it to the town hall, where our friend Ike and the policeman are gambling with a deck of cards and a box of matches.”

“Scoop and I happened to be passing the town hall,” Peg picked up the story, “when a familiar laugh punctured our ears. Creeping to a window, we peeped in. And there was dear old Ike and the copper gambling their heads off.”

“He’ll be ‘dear old Ike,’ ” grinned Scoop, “when we get through with him.”

“They’ve got the door locked,” Peg went on, “so that no one can come into the room and surprise them at their game, for the policeman, of course, is supposed to be in the street. The Strickers are there, too. That’s the best part of all.”

“Oh, boy!” yipped Scoop, hugging his stomach in his crazy laughter, “won’t there be a scramble, though, when we drop the pig in the window? It’ll be worth the two dollars that we paid, Jerry.”

Well, we got the boat ready for a hasty get-away, then we gave the pig a thick coat of machine grease. Dumping the greased porker into a bag, we followed Scoop down a couple of dark alleys to the building where the policeman and the bill poster were gambling with matches. The alleys were dark and we had to move slowly, feeling our way around big boxes and other obstructions. To keep the pig from squealing, we had fastened an old shirt of Peg’s over its snout.

When we came to the town hall Scoop pointed out the open window. We crept up and peeped in. The policeman and Ike were seated on opposite sides of a small table. The air was heavy with the stale smoke from a couple of hard-working corncob pipes.

“I’ll open it,” said Ike, putting in a match.

“I’ll stick,” said blue jacket, pushing in a match on his side of the table. He studied his hand. “Gimme three cards.”

“I’ll bet a couple,” said Ike, pushing some more matches into the center of the table.

“I’ll see you,” said blue jacket, “an’ raise you one.”

Scoop snickered.

“Here’s where we raise one. Get hold of the bag, fellows. Atta-boy! When I say ‘three,’ drop the pig into the window. I’ll loosen the gag so that he’ll be able to give them some nice sweet music.”

“I wish we could drop the pig on top of Bid Stricker,” giggled Peg.

“Maybe we can,” laughed Scoop. “For smarty’s sitting almost directly under the window.”

Well, we hoisted the porker into the air, dumping it into the room at Scoop’s signal. It gave an awful squeal as it landed on the floor. I guess the poker players were almost scared out of their wits.

“Holy cow!” roared blue jacket. “It’s a pig.”

There was a sound of tumbling chairs and the scurry of feet.

“Some one dumped it in the window,” yipped Bid Stricker.

“He’s comin’ your way, Ike,” roared blue jacket. “Grab him.”

There was a crash as another chair went down.

“You durn ol’ fool!” thundered blue jacket. “Why didn’t you hang onto him?”

“I tried to,” screeched Ike, “but he got away from me.”

“I’ll git him.”

There was another crash.

“Ouch! Jumpin’ Jupiter! He’s greased.”

Jerry Todd and the Oak Island Treasure.

WE DUMPED THE PORKER INTO THE ROOM AT SCOOP’S SIGNAL.

“I’m plastered with it. Jest look at me!” There was a whine in the high-pitched voice.]“It’s all your fault, Ham Bickel. I wouldn’t ‘a’ grabbed him if you hadn’t made me.”

We took a guarded squint into the room. The chairs and table were upset. The matches and cards were scattered every which way on the floor. Scared out of its wits, the pig was dashing first in one direction, then in another. The policeman and the Strickers, with smeared hands and faces, were trying to grab it. But the four-legged scooter, with its coating of grease, had no trouble keeping its freedom.

“We better beat it,” Scoop advised. So we streaked it down the alley to the dock. In a jiffy we had the Sally Ann untied and the engine churning.

How slowly we moved! Would the policeman hear us making our escape? Would he start after us?

My heart remained in my throat, sort of, until the lights of Ashton disappeared from our sight.