CHAPTER XII

THE BURIED TREASURE

We made short work of getting into our clothes—all except Red. Having stepped out of his pants without any recollection of where he had dropped them, he was having a sweating time in their loss. His teeth chattering, a hunted look in his bulging eyes, all he seemed able to say in his embarrassing predicament was: “Where’s m-my p-pants? My g-gosh, fellows! Who’s got m-my p-pants?”

We finally located the misplaced pants for him and shoved them at him.

“Snap into it,” Peg said sharply. “We aren’t going to wait for you all night.”

“It isn’t night,” Scoop corrected, squinting at his watch’s illuminated dial. “It’s two o’clock in the morning.”

We had taken note as we dressed that the scow was heading for the big wide waters. And in this discovery our puzzlement deepened. There would have been some excuse for the girl’s presence on the boat if it had been traveling in the direction of her home. But it wasn’t. Every minute the boat was taking her farther away from her home. We couldn’t understand it.

Was she trying to act smart with us? Was this a trick of hers to show us how much she knew about engines? We were angered in the thought. But we quickly sobered in the earnest conclusion that it was no skylarking whim that had brought her here.

“I began to think,” she spoke up, when we had appeared on the engine deck, “that you never were going to wake up.”

“How did you get here?” Scoop inquired, staring.

She pointed to a towed rowboat.

“It’s one of my grandfather’s boats. I was supposed to row all of the way to the island. He told me to. But I—I became frightened, and in my fright I lost my strength. It was so lonely and spooky on the canal.… I could hear things splash in the water. Then, when I was about to give up, unable to go farther, I came to your boat. Oh!… You can’t imagine how glad I was. For I knew you would help me.”

I saw how white she was.

“Here,” I offered quickly, “let me take the tiller.”

“What kind of help do you want?” Scoop inquired, when the girl had dropped into a seat on a box.

She didn’t make an immediate reply.

“Do you know where Oak Island is?” she spoke finally, lifting her face.

Scoop nodded.

“I have been sent there, in the dark, to bury this,” and she pointed to a brass box at her feet.

We stretched our necks at the indicated box, visible in the lantern’s light.

“What’s in it?” came Scoop’s natural inquiry.

“Bonds.”

“Liberty Bonds?”

“Twenty of them,” the girl said quietly, “worth a thousand dollars apiece.”

We stared at the speaker in sudden amazement. For we realized that twenty thousand dollars was a fortune.

“Grandfather and I have been to Oak Island a great many times. Once we camped there a week. And when it became necessary to-night to hide the bonds, to keep them from being stolen, the island was the only place he would consider.” She took a long look into the darkness, in the direction of the left wooded shore. Evidently she recognized her surroundings, for she added in confidence: “We’ll soon be there. And I’m supposed to stay there, in hiding, until he comes for me.”

Scoop found his voice.

“Twenty thousand dollars!” he cried, staring at the box. He looked up quickly, his eyes narrowed in sudden suspicion. “You aren’t stringing us?”

The girl wearily shook her head.

“I’ve told you the truth, even to the amount of the bonds.”

Our leader gave her a queer look.

“How do you know,” he said, “that we won’t take your bonds away from you and keep them?”

But she didn’t seem to hear him.

“I’m sorry,” she said, after a moment, “that I flew angry yesterday morning and said cross things to you. I found out later that the white-haired man you mentioned was my Uncle Feddon, my grandfather’s brother. It was generally supposed that he was dead. From the time he was a small boy he has been a sort of tramp. The last time he was home he forged Grandfather’s name to a check. There was an awful quarrel. When he went away that night he stole money and papers from the library safe.”

Scoop couldn’t pry his thoughts from the bonds.

“Your grandfather must be a queer man to keep his money and bonds in the house. My father has some Liberty Bonds, but he keeps them in a bank.”

After a moment’s flushed hesitation, the girl burst out:

“My grandfather is a queer man. He does things that can hardly be explained unless one concludes that his—his mind isn’t quite—”

“I understand,” Scoop cut in quickly.

“But you mustn’t think he’s crazy,” the girl cried, in added distress. “For he isn’t—not a bit of it. He’s just queer in a few ways. He should have kept the bonds in the bank. And why they were taken out of the bank is more than I can tell you. In fact, I didn’t know they were in the house until he came into my room a few hours ago, telling me that he needed my help. He said he was afraid of my uncle and the other man, both of whom were drinking and quarreling in the kitchen. Given the box of bonds, I was told to take the box to Oak Island and bury it under the big tree on the knoll. ‘There are twenty bonds in the box,’ Grandfather told me, trembling with excitement, ‘worth a thousand dollars apiece. You must help me hide them where your Uncle Feddon won’t ever be able to find them.’

“I asked him why I couldn’t take the bonds to Ashton, getting the help of the police. ‘No, no!’ he cried, more excited than ever. ‘You mustn’t do that, child. I don’t want the Ashton people to know that your uncle is here. They will arrest him. Do as I say. Take the bonds to the island. Bury them. They will be safe from your uncle there. And wait on the island until I come for you.’

“I didn’t like to think of going away and leaving him in the house with the quarreling men. So I ran to the garage, awakening the gardener, who sleeps there. Getting a lantern from him, I asked him to go to the house and stay with my grandfather. He asked me why I was up at such a late hour and what I was doing with the brass box. I didn’t tell him. Running to the dock, I untied one of the rowboats and started out. I rowed and rowed. I became frightened, as I say, and weak. Coming within sight of your boat, I first thought I would awaken you. I would tell you my story, I decided, and get you to take me to the island. Then I made up my mind to start the engine myself. I wanted to prove to you,” she concluded, looking at Red with the trace of a smile, “that a girl can be almost as handy with machinery as a boy.”

We were now in the big wide waters. There was a naked shore line to the right of us, barely discernible in the darkness, but on the left there was nothing but an expanse of water as far as our eyes could see. Here the channel was marked with parallel rows of white piles set a hundred feet apart. To get to the island, on our left, it would be necessary for us to make a right-angle turn, passing between the piles on the left-hand side.

This we did successfully by slowing the engine and using poles, carried on the boat for that purpose. The water was shallow outside of the channel. And of no desire to get hung up on a mud bar, we let the boat sort of crawl along in the darkness. The island was ahead of us, a vague black shape, and when we were within two hundred feet of the shore we stopped. Putting out our anchor, we rowed to shore in the girl’s boat.

Landing, Peg went ahead with the lantern, leading the way, the rest of us following single file. Taking a winding course amid bowlders and through thickets we came to the island’s summit, where the granddaughter had been instructed by her queer relative to bury the brass box.

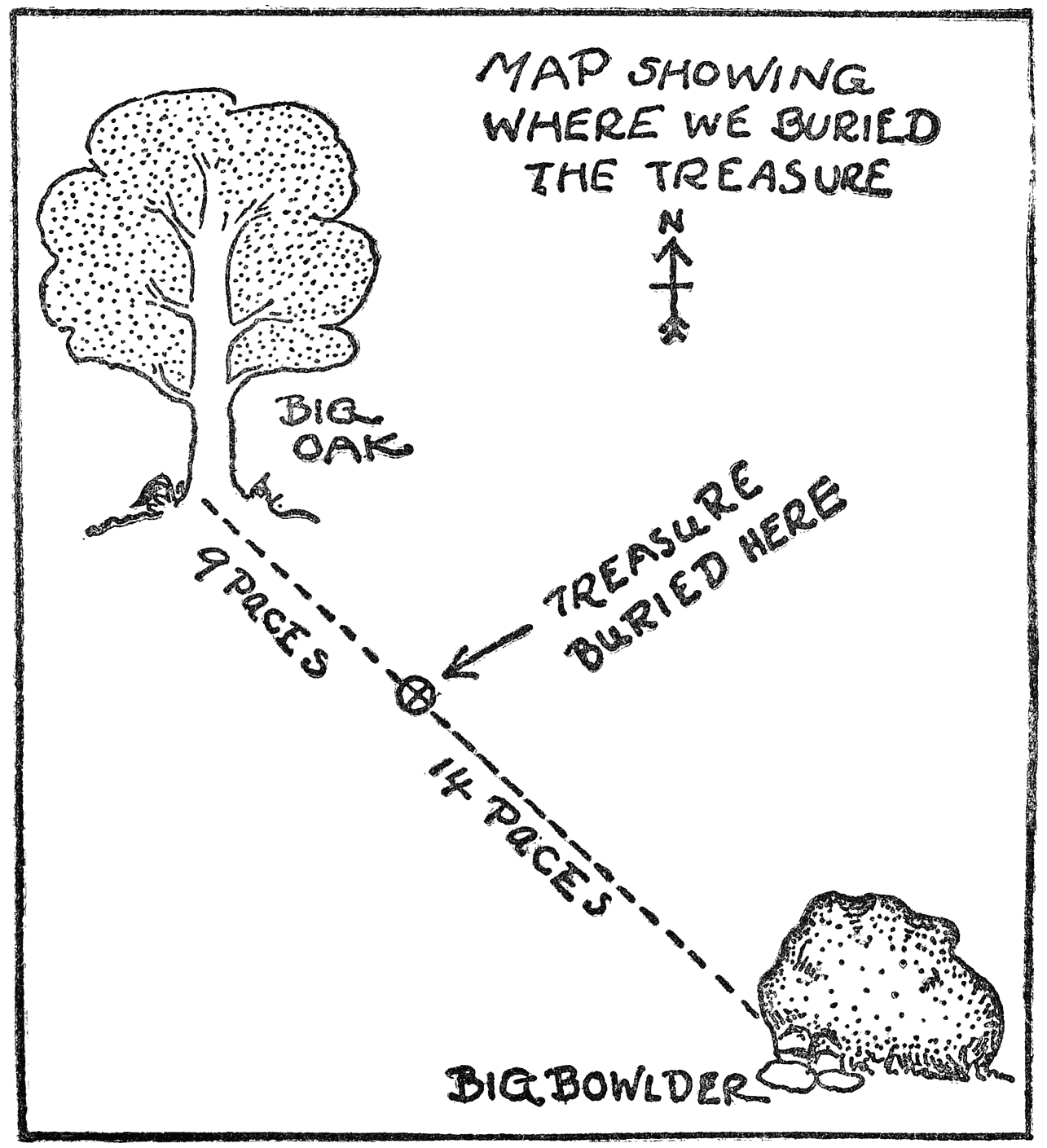

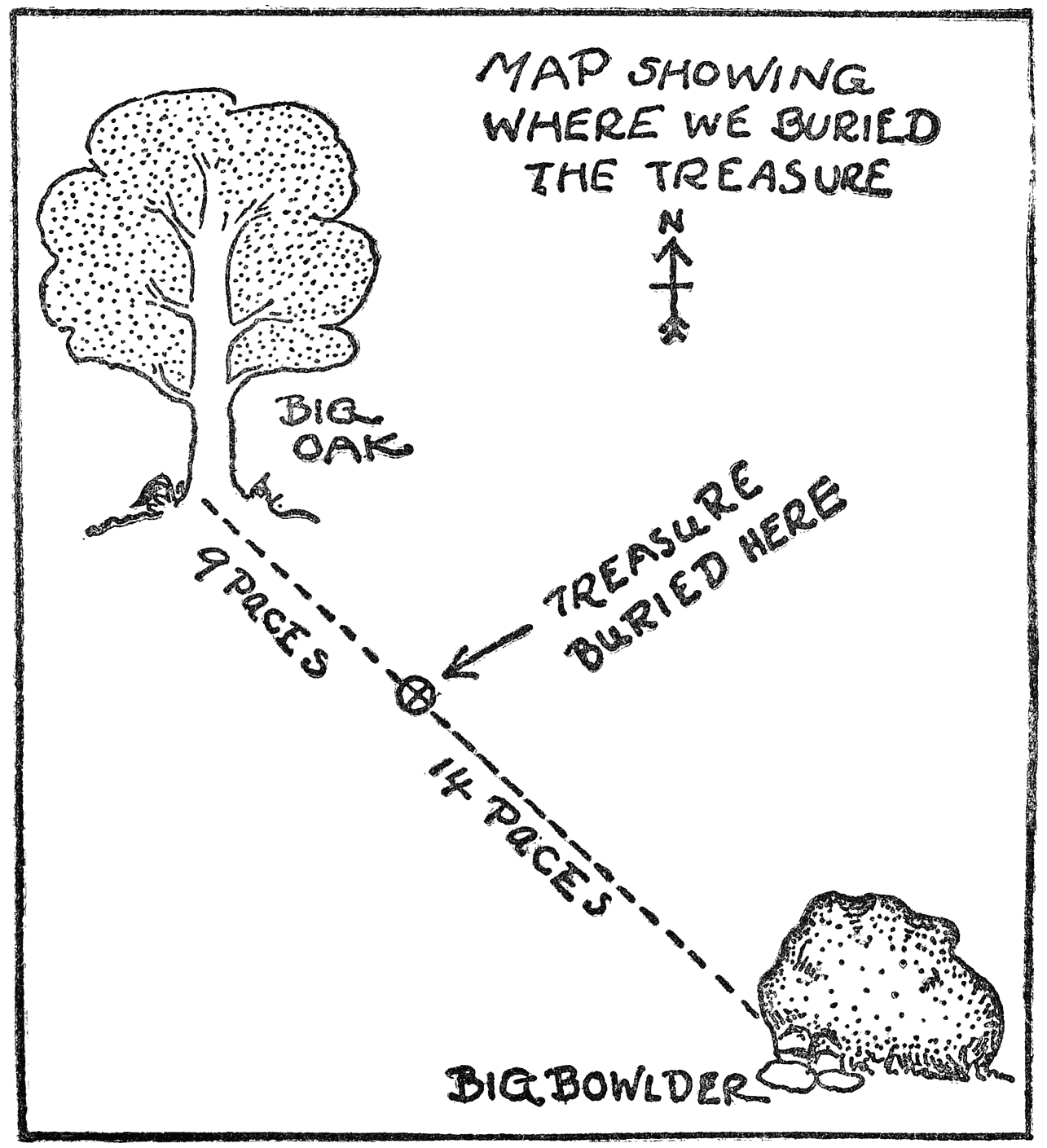

At a spot selected by Scoop we dug a hole about two feet deep, into which the box of bonds was dropped and covered up with loose dirt. There was an unusually large bowlder a short distance away. Having dug our hole in line with the bowlder and the island’s largest tree, Scoop now informed us that the spot where the treasure was buried was exactly fourteen paces from the bowlder and nine paces from the tree. I held the lantern while he drew a map of the treasure’s hiding place. The girl said this was unnecessary. But, that didn’t stop him. It was customary in burying treasure, he said, to make a map of the treasure’s hiding place. We wouldn’t be doing the job right, he further declared, if we omitted the map. What he drew will be found on the opposite page.

It was now close to four o’clock. No one had any thought of going to sleep; so we decided to bring our food on shore and have an early breakfast.

Scoop and I rowed to the scow, talking and laughing. It was almost unbelievable, we said, that we had just helped a girl bury a twenty-thousand-dollar fortune in Liberty Bonds. We wondered if we wouldn’t wake up, after all, to learn that our adventure was nothing more than a crazy dream.

MAP SHOWING WHERE WE BURIED THE TREASURE

Coming within a few yards of the scow, we were startled by a sound of footsteps. Instantly I thought of the ghost, and, reversing my strokes I quickly brought the boat to a stop.

“If it is the ghost,” Scoop whispered, squinting at the scow, a squat black patch on the darkened water, “now’s our chance to find out who it is.”

“I’m like Red,” I said, admitting to a lack of courage. “I almost wish I was home.”

“Shucks! It’s a friendly ghost.”

“It was yesterday,” I said, with a nervous shrug. “It may be an unfriendly ghost to-day.”

He stood up and took a long look ahead.

“Can you see anything, Jerry?”

“Nothing but a black patch.”

“I thought I saw something white.”

“You probably did,” I shivered.

“Row closer.”

“Let’s wait until daylight.”

But he wouldn’t listen to me. And reluctantly I dipped the oars in at his orders and brought the rowboat against the scow’s side. In another moment he had scrambled on board the big boat, disappearing from my sight.