CHAPTER XXII

SEARCHING FOR THE LAND GRANT

Betsy Clossen had hardly slept a wink the night following her discovery of the real identity of the mysterious Trujillo. She kept thinking and thinking of a possible hiding place for the lost papers which, when found, would restore to the family of Don Carlos Spinoza their rightful estate.

“How I do hope I may be the one to find them,” was her last conscious thought at night and her first on waking the next morning.

It was not yet daybreak, but Betsy quietly arose, dressed and tiptoed out of the room without having disturbed Margaret from her peaceful slumber.

Reaching the kitchen, Betsy stood for a moment trying to think where she would begin her search. Then, suddenly, she remembered something. The peon had been trying to pry the stones from the walls of the great old fireplace. There might be a secret opening with a stone fitted in to conceal it. Lighting a lantern, for it was still dark, Betsy stole into the long silent front room, not without many a tremor of fear, for, even now, when the mystery was nearly solved, the place seemed haunted with the many foreign faces gazing down at her from the walls.

Trying not to look at them as they were revealed one by one in the dim light of her lantern, Betsy went at once to the fireplace. She did not attempt to pry out the stones, but tried to find one that looked as though it had not been securely fastened and could easily be removed.

However, each stone within her reach was cemented to its neighbor, and, convinced at last that her search at the fireplace was to be unrewarded, she turned away. Walking to the center of the room, she stood looking about, trying to recall all of the detective stories she had ever read.

There was always a secret panel in the wall which revealed a hidden treasure if one could but find the spring, but these walls were adobe and there were no panels. True, there was the small dark cellar into which the elevator chair descended, and from which spiral ascended, and yet, did she quite dare to go down in that dungeon-like place alone while the rest of the household slept? Betsy suddenly lifted her head and listened intently. She had heard soft foot-steps approaching in the kitchen, then the door opened cautiously. It was Margaret who appeared, pale and wide eyed.

“What in the world are you doing here, Betsy?” she inquired, as she advanced into the room. “I woke up and found you were gone. I thought you might be walking in your sleep. You were so restless all night and kept saying things.”

“What did I say?” Betsy inquired curiously.

“Nothing that made any sense as far as I could tell,” was the reply. “You kept mumbling every now and then, but once you sat right up in bed and said in the queerest voice: ‘Three crosses. That’s where the papers are.’ I shook you and whispered, ‘Betsy, what are you saying?’ but you lay down again and did not reply. Then I realized that you had been asleep all of the time.”

The eyes of the young would-be detective were glowing with sudden inspiration. Seizing the wondering Margaret by the arm, she exclaimed: “Come with me, Megsy!” and before the other girl could realize what was happening, she was being dragged across the kitchen and out of the house where the desert lay silent and uncanny in the deepest darkness of the night, which comes just before the dawn.

Margaret, being of a more timid nature, was truly frightened when she saw that Betsy was dragging her farther and farther away from the ranch house and toward the lonely sand hills. The truth of the matter was that at any other time, Betsy would have been frightened also, but at present she was possessed of just one idea which was that the papers for which they were searching were hidden, in all probability, at the Shrine of The Three Crosses. When Margaret told her what she had said in her sleep, Betsy believed that the message had come to her as an inspiration, and so sure was she of this, that for the moment she had become unconscious of fear; too, she had forgotten the lean, gaunt wolf of the desert, whose long drawn-out wail had so startled her on the occasion of her last visit.

“Betsy, let go of my arm,” Margaret managed to gasp, “and tell me where we are going.” Then a terrible thought came to Megsy. What if Betsy should be walking in her sleep after all, and what if she were taking them both to some place where harm would befall them. So convinced was Margaret that this was the real explanation of her friend’s actions that she whirled about as soon as Betsy loosened the clasp on her arm and raced back toward the ranch house. A light appeared in the small adobe, then, as she was about to pass, the door opened and Trujillo stepped out. In the grey light of the early dawn, Margaret’s flying form was easily seen and the overseer, much mystified by the appearance of one of the girls in such seemingly terrorized flight, quickly overtook her.

“Senorita,” he exclaimed when she turned a white face toward him. “What is the matter? Where have you been? What have you seen?”

“Oh, I am so glad you came,” Megsy replied. “I was going after Peyton. Betsy Clossen is walking in her sleep. I just know that she is, and she’ll come to some harm if we don’t bring her back. She says the queerest things about lost papers being hidden at the Shrine of The Three Crosses. I never heard of such a place. Did you, Senor?”

Trujillo replied in the negative. He had never heard the peons mention a shrine and surely they would know if there were one.

“Wait here, Senorita, I will get horses and we will follow your friend.”

When Margaret had deserted Betsy, for a moment the young would-be detective felt a strong desire to turn and race after her, but she would not permit herself to do this. She was so eager to find the lost papers and she was more than ever convinced, as she thought about the matter, that they were probably near the shrine. This had been the daily haunt of the old Don who had prayed that his estate might be restored to him. What would be more natural than that he would conceal the papers there, believing, as he probably did, that his political enemies when they found him would confiscate the documents, making it impossible for him to prove that the land grant had really belonged to his ancestors.

As Betsy neared the lonely sand hills, she dreaded more and more the moment when she would enter the sheltered dug-out where she had found the shrine. She knew that, loud as she might call, no one would hear.

“Oh, I can’t go on! I can’t! I can’t” she exclaimed, her fearlessness suddenly deserting her. Then it was that she heard something weird indeed.

In a voice that sounded almost like a mournful echo, some one was calling. Then in her heart there was a sudden joyful realization of the truth. Some one was shouting her name and the sand hills were sending back the echo: “Betsy, where are you?”

“Here! Here!” she replied as she ran out to meet the approaching riders. Of course she might have known that Margaret would soon return with one of the boys.

She was glad to recognize that the other rider was Trujillo. As they drew near, the Spanish youth saw that the girl standing alone near the sand hills did not look as courageous as her fearless actions had implied. Instead her face was pale, her eyes wide, although her expression was one of gladness, because she was no longer alone.

Betsy was not asleep, of that Trujillo was convinced. Leaping to the ground, he exclaimed: “Senorita, what mad fancy brought you to this lonely place before the dawning of the day?”

“Oh, senor, the papers! I am sure, as sure as one can be when one does not really know, that they are hidden somewhere near the Shrine of the Three Crosses.”

“Three Crosses?” Margaret repeated. “That is what you said in your sleep.”

“Where is the shrine, senorita?” Trujillo inquired. Betsy led the way between the sand hills to the small dug-out in which were three large wooden crosses. One had fallen to the sand, another leaned over, but the third stood erect. Trujillo bared his head and knelt upon the sand for a moment in prayer. The girls could understand that the lad must indeed feel awed to find himself before the shrine which had been so often visited by his grandfather, Don Carlos Spinoza. He soon arose and when he turned toward them they knew that he had been deeply affected. Then in a tone of conviction he said:

“Senorita, your dream, I am sure, is to be fulfilled. My grandfather’s last words were: ‘The land grant at the Three Crosses.’ If he had meant at the Three Cross ranch, he would not have used the plural.”

Then Trujillo stood gazing about him, thinking intently. He was trying to decide the probable hiding place of the document he sought. Suddenly his thought was interrupted by an exclamation from Betsy, the girl was gazing as though fascinated at the large wooden cross standing erect between the two that had fallen.

“Senor,” she said, “there must be some reason why that cross in the center has stood while the others have not. It must have a firmer foundation. Do you not think so?”

“I do indeed,” was the reply of the youth, who at once knelt and began digging at the base of the cross. The sand on top was soft, but, as he advanced, he found that it became more difficult to remove. The action of the rain and sun during the ten years since the cross had been erected had hardened it until it was the nature of sand stone.

He arose. “Senorita Betsy,” he said, “our surmise was not correct after all. There seems to be nothing holding this cross but the hardened sand.”

Betsy was keenly disappointed, although she was not entirely convinced. Trujillo left the girls standing alone while he advanced farther into the cave-like dug-out. It extended deeper into the sand hills than he had at first supposed. He did not advance far, however, but stopped suddenly and gazed intently into the interior, and then, assuming an attitude of seeming indifference, he returned. He did not wish to startle the girls by telling them that he had seen two green eyes gleaming in the darkness at the back of the cave. He believed the creature to be either a mountain lion or a coyote, which of late had been killing the young calves.

“Senoritas,” he said in a voice which did not betray his real concern, “our friends at the ranch house will be troubled because we do not return. The breakfast hour is long passed. I suggest that we come here later in the day, bringing with us a pick and shovel that we may make a thorough investigation.”

As he spoke, he led the girls away from the crosses to the place where the ponies were.

“Promise me you won’t search for the papers unless I am with you,” Betsy implored. The Spanish youth smiled at the pretty, flushed face of the pleading girl, as he replied: “I promise, Senorita.”

All that morning Betsy watched and waited. She almost lost faith in the promise of Trujillo when, at last, she beheld him returning from the sand hills, accompanied by Peyton, but when she saw that they were armed with guns and did not carry a shovel or pick, she knew that they had been on some other mission.

Trujillo rode to the ranch house and entering the living room, he said to the eager girl: “If you are ready, Senorita Betsy, we will go at once.”

Margaret and Virginia were busily employed in the kitchen, but they glanced up when they heard the cantering of horses’ hoofs beneath the window.

“I wonder where Betsy and Trujillo are going,” Virg said. Margaret, who had been sworn to secrecy, did not reply.

“Oh, I presume they are still searching for the land grant papers,” Megsy said. “I’d heaps rather be in this sunny, comfortable kitchen making pies, wouldn’t you, Virg?”

The older girl smiled. “Perhaps it is well that we have different interests,” she replied. “Some of us like to do adventurous things and some of us like to do the quiet, homely things, but I really enjoy both the desert life and then home life.” Then she added, with one of her radiant smiles: “I do believe, Megsy, that I am a natural born enjoyer.”

“You are indeed,” her friend responded, admiringly. “You always seem so happy and contented, Virg, wherever you are. Tell me your secret.”

Virginia put her arm about Margaret and drew her down to the sunny window-seat, as she replied: “Mother often told me that we ought to let our lives blossom as a flower unfolds, just peacefully and trustingly, enjoying the song of a bird, and the warmth of the sun and whatever beauty is near us. Many people try to force their life blossoms open and are so continually reaching for something beyond, that they never really enjoy the loveliness that is near them and so they become worried and weary. Every morning I ask myself: ‘What happiness can I find and give today in the place where I am? That keeps me contented and happy.” Then springing up, she laughingly added: “Yum! Doesn’t the pie smell good? I do hope everyone will be here in time for lunch.” But it was long after the lunch hour before Betsy and Trujillo returned.

In the meantime Betsy and Trujillo had reached the sand hills and were standing in front of the three crosses. Trujillo glanced into the cave beyond the shrine. Little did his companion know that in the darkness there was a newly made grave.

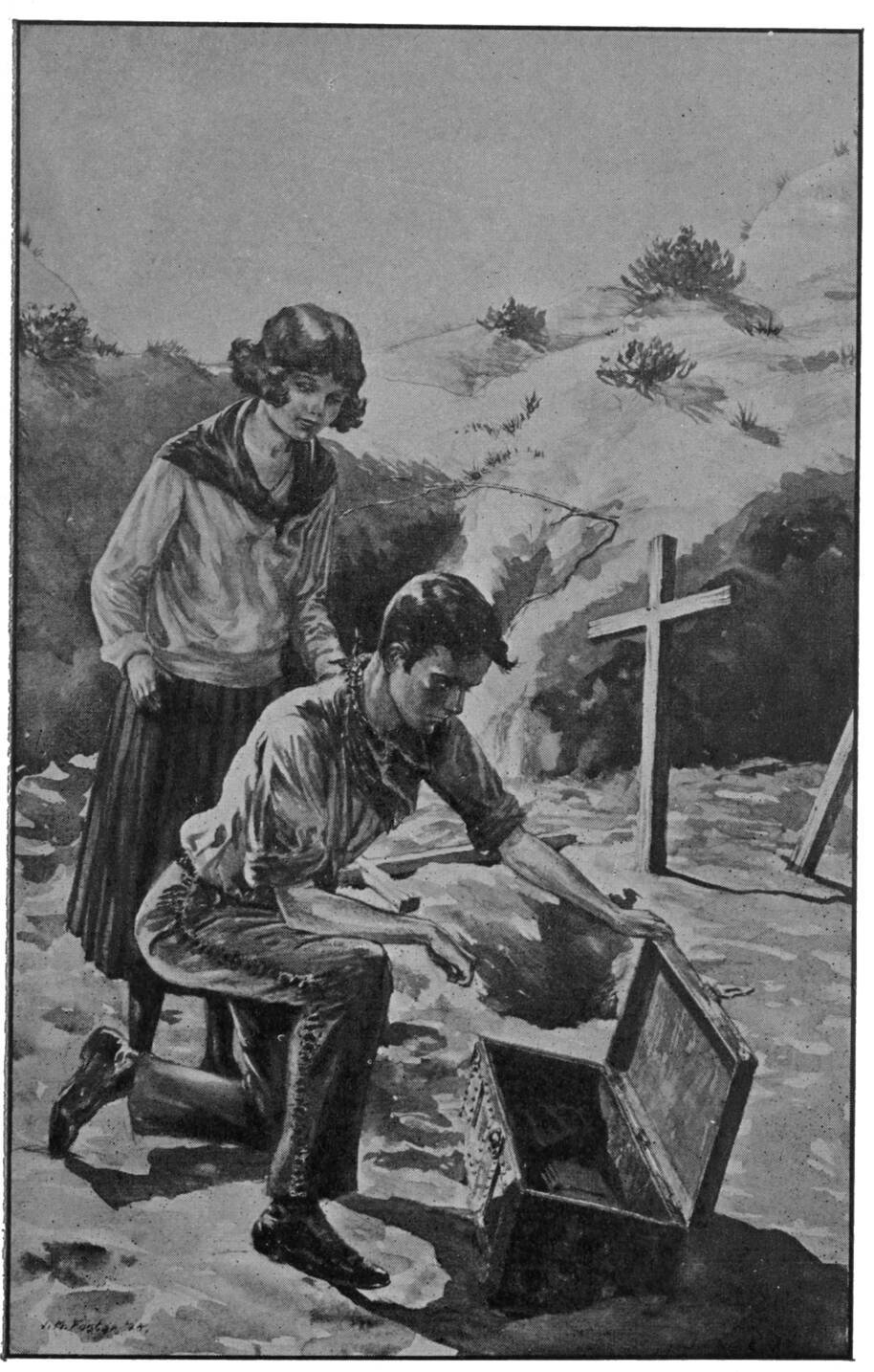

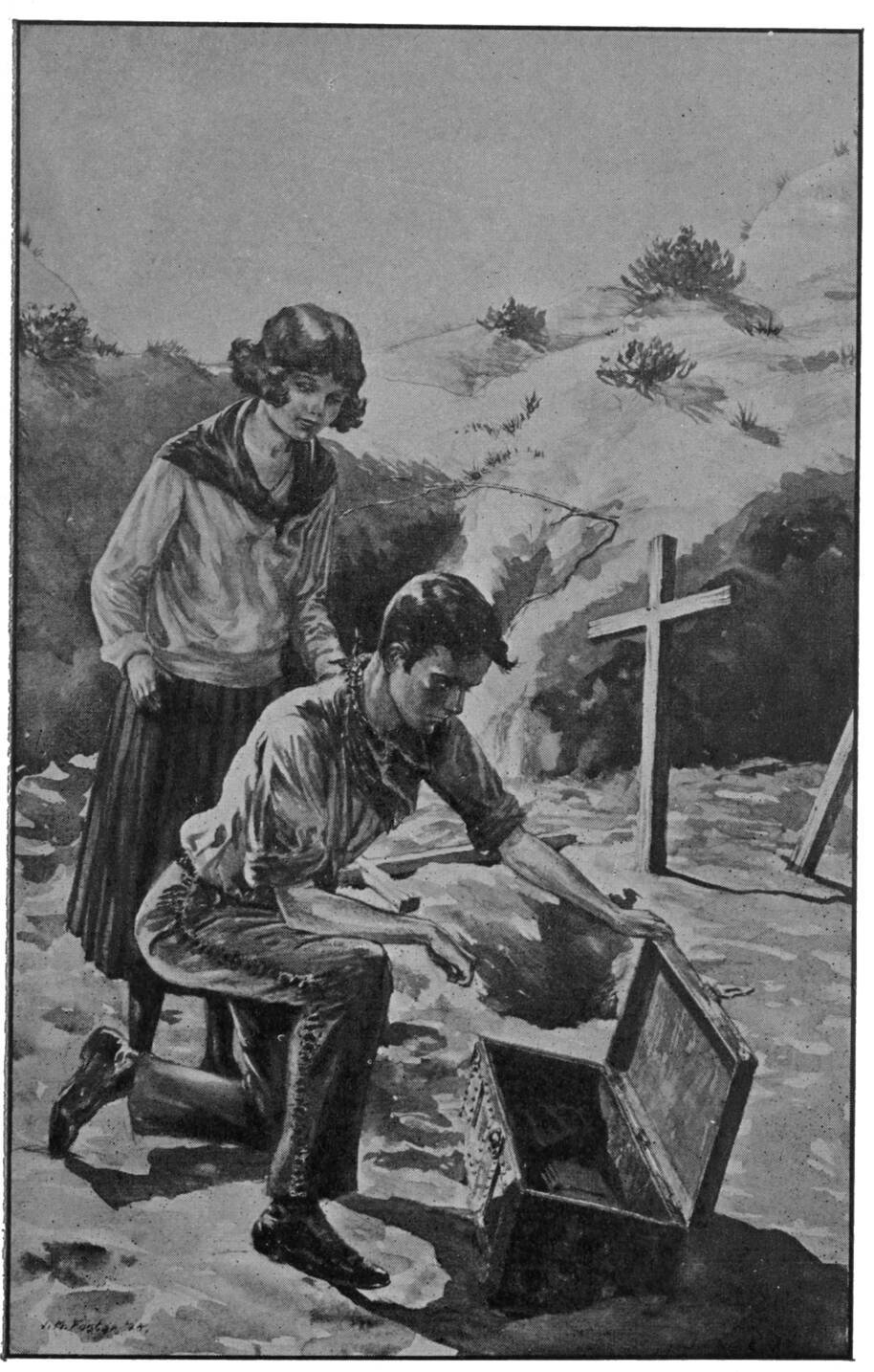

At Betsy’s suggestion he began at once to dig beneath the middle cross. The pick was needed to break the sand stone, but suddenly it struck something that did not break. One corner of an iron box was revealed, which however, was so firmly imbedded in the rock that it took a long time to entirely free it. Betsy, after the first exultant exclamation, had stood silently watching.

How she did hope that this box contained the land grant document that the mother and sister of Trujillo might have their home restored to them.

When at last the box was freed, they both knelt beside it to see if the key hole was as queerly shaped as was the key that the mother of Trujillo had given him. When they found that it fitted exactly, Betsy’s joy could no longer be restrained, and leaping up, she clapped her hands and uttered varied exclamations of delight.

Trujillo glanced at her with a happy smile. “Senorita,” he said, “before I open this box, I want you to promise me something. If the papers are here, and if our home is restored, will you and your friends come some day, and visit us? My mother and my sister Carmelita will welcome you gladly.”

Then the key turned and the box was opened. There was a glad cry from the girl who had been watching breathlessly, for there lay a packet of yellowing papers. Placing them in his pocket, the Spanish lad rose and held out his hand to his flushed and excited companion. “Senorita Betsy,” he said, his melodious voice tense with feeling, “I thank you for your interest and my mother and sister will want to thank you when, with your friends, you can visit us.”

Then leaving the heavy iron box in the sand by the crosses, these two rode back to the ranch house to tell the others that, at last, the long lost papers had been found.

There lay a packet of yellowing papers.

“I shall leave for Mexico tomorrow if Monsieur Peyton can spare me, but before I go I shall return alone to the shrine and leave the three crosses standing, firm and erect, in the memory of my grandfather.”

And this Trujillo did, going to the shrine at sunrise on the following morning. Then directly after breakfast, the Spanish youth rode away to the south.

“Girls,” Betsy cried, “how I do wish, before I have to return East, that we might visit the beautiful Carmelita Spinoza.”

“Stranger things than that have happened,” Virginia replied.