CHAPTER VII

For about two years there has been great doin’s in Hamen Smith’s family, owin’ to Tamer Ann’s wantin’ to make Anna marry a young old chap who come down from New York village to look at some grave-stuns in the buryin’ ground by the old Dutch Reform Church up in Zoar.

There wuz some dretful aged stuns there with old Dutch names on ’em, and the young old feller wuz in hopes he would find some ancestors there. He had piles and piles of ’em before he begun to hunt there, enough for comfort and more, too, but he wanted some more, so sure it is that the more you have the more you want.

And so he come down a purpose. He didn’t find any ancestors, but he found Anna. And he jest stayed along and stayed along. He had only got board at the tarven for two days, but he stayed seven weeks that time and come down agin frequent after that, and the next summer spent the hull of his summer there.

Anna wuz engaged to Tom Willis, a good lookin’ and good actin’ young chap, and Tamer Ann had never lifted her finger or said a word to stop their intimacy or engagement. But when this old young feller come she jest commanded Anna to not think of Tom Willis any more, and ordered her to be polite and sociable with this young old man. Curious how some mothers can act, ain’t it now?

I liked Tom Willis. He wuz studyin’ law under Thomas Jefferson, he had been under him for several years now, and Thomas J. thought everything of him, and said he wuz bound to make his mark in the world. Yes, I liked Tom and Tom liked me. But I had never seen the old young man till the day we went there a-visitin’, bein’ invited special by Tamer.

It wuz a pleasant drive over there, and I got up middlin’ early and got a good breakfast, a very good one, knowin’ that my Josiah’s demeanor for the day depended a good deal on it. And I wanted his liniment to be smooth and placid, for nothin’ gauls a woman more than to have her companion kinder snappish to her when she takes him out in company. She knows the wimmen are all comparin’ his liniment with their own husband’s liniments, and she wants him to show off to good advantage. She has a pride in it.

So I cooked, in addition to my other vittles, a young tender chicken, briled it, and had some nice warm biscuit, and some coffee, rich, yellow, and fragrant, with lots of good cream in it. And I had other good things accordin’. I did well, and Josiah’s liniment paid me; all the way to Hamenses his mean wuz like a babes for softness and reposeful sweetness. He twice murmured words of affection into my right ear, he sez, “Dear Samantha,” twice, such wuz the stimulatin’ and softenin’ effects of that coffee and broiled fowl. Oh! if female wimmen would only heed these words of warnin’ and caution from their sincere friend and well wisher. If they would only spend the strength they take to try to convince their pardners that it is onmanly to snap ’em up and be fraxious and puggecky to ’em, especially before folks and other wimmen, if they would only spend this time in preparin’ food, if they would only accept the great fact that men’s naters are made jest as they be, and the effect of food on their naters is jest what it is, if they would only accept these two great philosofical facts, and not argue and contend and try to understand why it is so, or how, or is it reasonable that it should be so, or anything about it. Simply accept it, dear married sisters, and guide them gently on by this safe and assured way. It will not fail you, no, Samantha has tried it in the balances and has never yet found it wantin, for twenty years and more that has been my safe weepon and my refuge in times of trouble.

I know that I have repeated these words of advice and warnin’ anon or oftener, but it is only because I have such a tender feelin’ for my sister wimmen who are placed in the tryin’ position of pardners. And I want ’em, oh, how I want ’em! to do the best they can with what they have to do with. But I am eppisodin’, and to resoom.

We sot out for Hamenses about half-past ten on that pleasant mornin’. All over the dooryard and about the house hung the soft silence of the early mornin’. The birds wuz singin’ in the lilock bushes by the clean doorstep. The branches of the trees hung low down in the orchard. The sunshine lay in the dooryard in golden patches flecking the green grass between the shade trees and on the clean painted doorway and the winders. And I knew and Josiah knew that we shouldn’t see no such sunshine agin till we see this same light shinin’ in our dooryard and the white curtained winders of home.

Well, we had a pleasant drive, with no eventful events to disturb it till we got near to Hamenses house at about a quarter to twelve. As we wuz a-goin’ down the hill pretty clost to his house I methought I hearn sunthin’ wrong, a rattlin’ sound amongst the iron framework of our conveyance, and I mentioned the fact to my pardner. He then intimated that I had frequently called his attentions to similar things on similar occasions (he didn’t word it in this way, no, it wuz a shorter way and fur terser).

But I knew I wuz in the right on’t, and begged him to git out and see about it. But he vowed he wouldn’t git out, he even made a oath to confirm it. “Dum” wuz the word he used to confirm the fact that he would not git out. But the very next minute one of the wheels come off, and he did git out. Yes, he got out, and I did, too. He got out first, and I kinder got out after him. It wuz sudden!

Everything seemed sort o’ mixed up and sick to the stomach to me for quite a spell. But when conscientiousness returned I found myself layin’ there right in my tracts, and what made it more curious and coincidin’ I had a bundle of tracts that her old pasture, Elder Minkley, had sent to Tamer Ann. He worried over her readin’ dime novels so much, and he had sent her these tracts, “The Truthful Mother and Child; or, The Liar’s Doom,” and one wuz, “The Novel Reader’s Fate; or, The Crazed Parent.”

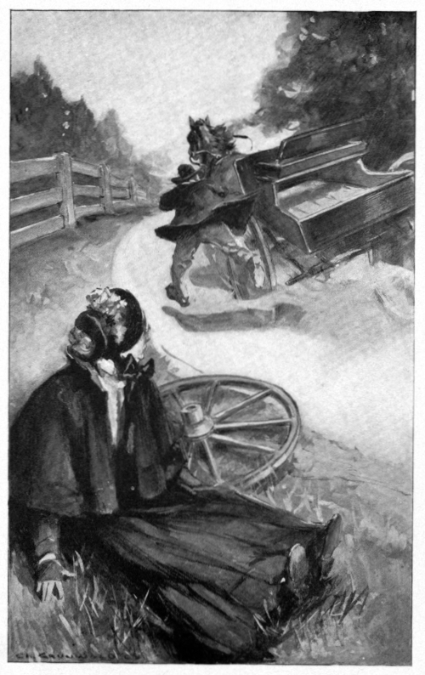

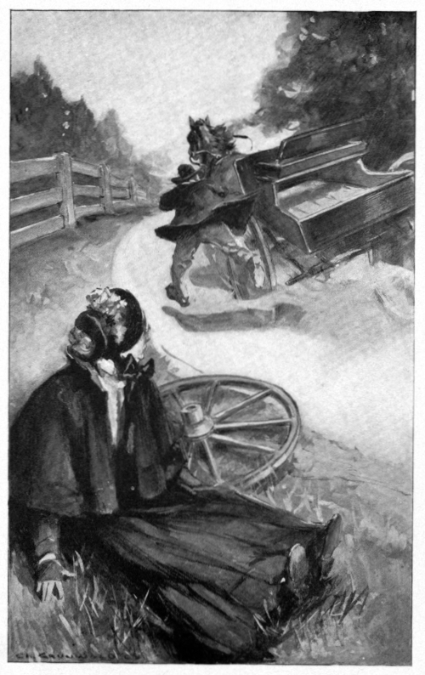

Well, I lay there feelin’ curious, Josiah tryin’ to keep the horse from tromplin’ on me, and he wuz, I could see, agitated in the extreme about me, though I had said faintly from where I lay:

“I hain’t killed, Josiah,” and, as he seemed by his looks to doubt my assurance and mourn for me as lost, I sez agin:

“I am not dead, Josiah,” and I added in faint axents, “Have I bent my bunnet much?”

And he sez, “Dum the bunnet!” And I didn’t blame him a mite when I come to think it over. How sure it is that sudden reverses of fortune brings out the flower of love in full bloom! As I lay there kinder stunted I felt that I loved my companion and wuz well aware how he worshipped me.

I spoze my remark about the bunnet had took the edge off from his anxiety, and he felt that I wuz alive and considerable comfortable. And at that very minute the mair, bein’ hit on the heel by the thill Josiah wuz liftin’ up, kicked up both of the hind ones (heels) and sot off back to Jonesville, my pardner runnin’ after her as he still had holt of the lines. As I said I laid there feelin’ dretful curious, for I couldn’t for my life git up, I spoze I wuz stunted by my fall.

But as I looked back the way we had come and beheld my pardner disappearin’ round the bend of the road in the wake of the mair, I see comin’ towards me from that direction a queer lookin’ tall chap with long, small limbs and a high collor and cane, and, as he approached me, he stopped and looked down on me through a eyeglass that hung round his neck, in a queer way, though polite, and sez he:

“You got out sudden, you know.”

“Yes, I know it,” sez I faintly, “but if I had a little help I could git up agin.”

But he didn’t offer to help me. He looked at me through that eyeglass and sez he, holdin’ tight to his cane and kinder jabbin’ it into his mouth now and then:

“You fwightened me, you know; I pwespiah now from fwight.”

THE MAIR SOT OFF BACK TO JONESVILLE, MY PARDNER RUNNIN’ AFTER HER, AS HE STILL HAD HOLT OF THE LINES.

“From what?” sez I.

“Fwom feah, you know; feah.”

“Oh,” sez I.

Agin he jabbed that cane of hisen into his mouth, and sez he, not offerin’ to help me a mite, but standin’ off and eyin’ me like a one-eyed owl: “Are you shuah you have not sustained any sewious injuwy?”

“Yes,” sez I, “I hain’t hurt much, I could git up if I had a little mite of help.”

“Youh fouh ahm now, can you waise it?”

I reached out my arm, feelin’ considerable like a horse, or mebby it would be more proper if I should say I felt some like the old mair, she had sunthin’ the matter with her fetlock. And he continued as he stood there with all the willowy grace of a telegraph pole, and as tall as one, so it seemed to me:

“Do you feel any pain like basilah menigitis, you know? Do you feel any uneasiness in youah pewicardium?”

Follerin’ his train of idees almost onbeknown to myself, I sez faintly, “I never knew till this minute that I had one, but I guess it is pretty middlin’ comfortable; I am obleeged to you.”

“Oh, I feel welieved if you haven’t injured youah pewicardium, for that would have been almost suah to bwing on basilah menigitis.”

I give up that I wouldn’t git no help from him, and I sez, “If you would just go to that house ahead and tell Hamen Smith’s folks that I have come I would be glad.”

I did it partly to git help and partly to git him out of my sight, he did look so dog queer standin’ there gnawin’ at that cane of hisen, with his stiff collar holdin’ up his ears, and his clothes that tight that I spozed mebby that wuz one reason he didn’t offer to help me up, the other reason bein’ that he didn’t know enough. But, truly, it would have been a rash and hazardous proceedin’ on his part to bend over much, and I didn’t promulgate any desire for his help after I took a minute’s thought about it. But when I spoke of Hamenses he sez, “I am going there.”

“Are you?” sez I. “Then mebby they will want to see you right off. I’d go on if I wuz in your place and tell them that I have come.”

“Yes, I will go,” sez he. He seemed good natured enough what there wuz of him (his mind, I mean). And he started off lookin’ like a tall, slim fork walkin’ away. But he turned before he’d gone more’n a step or two and come back, and sez he:

“Youah shuah now?”

“Sure of what?” sez I.

“Shuah you have not sustained any sewious injuwia?”

“Yes! yes!” sez I, gittin’ wore out. “And I’d like a little help to git up; I wish you would hurry.”

And then he went on a few more steps and come back agin, and I sez, “For the land’s sake! What do you want now?”

“Youah cahd, you know, you haven’t pwesented me with youah cahd.”

Sez I with dignity, or as much as I could have layin’ most flat in the middle of the road, “This is a pretty place to talk of playin’ cards or any other game, I settin’ flat down here in the road and can’t git up. You had better start on to once and git away from me,” sez I, “and tell Hamenses folks I’ve come.”

“I haven’t the pleasuah of knowin’ youah name,” sez he, lookin’ sort of pale round the mouth, and his eyes lookin’ big and round. I spoze I skairt him some by my lofty mean (lofty under difficulties).

“I couldn’t tell, youah know, who had come, youah know.”

“That is so,” sez I, “I forgot. Tell ’em that Josiah Allen’s wife has come.”

“Oh, Josiah Allen’s wife, I have the gweatest pleasuah in meeting you. I have heard of youah, youah know.” And he took off his hat and bowed low to me. I sithed, for I believed then and believe now he would have stood there for an hour holdin’ his hat in his hand and bowin’ to me and actin’, and he looked more’n a mile high, too, I a-settin’ there helpless. But I looked at him that witherin’ that he turned agin and hurried off as fast as his long legs would carry him.

He hadn’t got more’n a few steps away before a light buggy come rollin’ on swift, and who should it be but Tom Willis goin’ on some law bizness for Thomas J. up beyend Zoar. How curious things will turn out, now this wuz jest as curious as it wuz for Crusoe to discover Friday.

I guess I didn’t have to talk to Tom Willis about his helpin’ me. No, he flung the lines to the boy who wuz with him, and he wuz out of that buggy and by my side in less than a minute. And it wuzn’t a minute more when he jest lifted me right up and held me for a minute or so, for I wuz giddy and sort o’ stunted, and then he helped me into his buggy and we drove on to Hamenses and got there long enough before that long legged chap had arrived. He couldn’t walk fast, so he told me afterwards, on account of his “pespiwin,” and then he had “dwopped” his cane, “you know.” And I could see for myself jest what a time he had had pickin’ it up. For the land’s sake! I don’t see how he ever done it, and so I told Josiah.

But, anyway, Tom Willis took me out of the buggy jest as tender and careful as if I had been his own Ma, and, leanin’ on his strong arm, I arrived at Hamenses door and went in, Tom leavin’ me at the doorsteps and not goin’ in, for reasons to be named hereafter. But as I stood on the front stoop, and Tom turned to go away, I see a red, red rose come a-circlin’ through the air from right over our heads and fall at Tom’s feet, and he took it up and kissed it, for I see him, and put it in his bosom. And then he turned and looked up into a window overhead, and no light of the mornin’ sun breakin’ through a cloud wuz ever brighter or more luminous than the glance and smile he gin to somebody overhead. But it wuz all done in a minute, and Tom wuz gone, and in a minute more Anna Smith wuz in my arms, with both her sweet young arms round my neck and her soft pink cheeks pressed clost to mine. I think enough of Anna Smith, and she thinks enough of me.

Well, Hamenses wife come runnin’ in dretful glad to see me, she wuz in the back kitchen givin’ orders to her hired girl, Arabeller, and Hamen come in, too, real cordial actin’, he wuz in the back yard at work, and Jack come boundin’ in and most eat me up, he wuz so glad to see me. And bimeby Cicero come in with his fingers between the pages of a dime novel, and shook hands with me in a absent mekanical way, but he didn’t seem to sense my bein’ there much of any, and what he did sense didn’t seem to be an overagreeable feelin’, real cool and indifferent he acted. I guess Tamer noticed it, for she spoke up and said:

“Cicero wuz such a reader, he had such a great taste for books and literatoor, he wuz so much like his Ma.” And then she patted him on his head, but he didn’t seem to mind that any, he wuz fairly bound up in his book, it wuz “The Brave Bold Young Bandit; or, The Farmer Fool Outwitted.” It had a yeller cover and painted on it wuz a innocent lookin’ young farmer boy, kneelin’ at the feet of a bandit boy with bold flashin’ eyes, embroidered uniform and tall feathers in his hat. I looked at it when he laid it down for a minute that day, and I see that it would be real instructive in learnin’ a boy to despise honest labor and heart merit, and honor dashing wickedness and crime. He had a cigarette in his hand when he met me, and he had one in his hand or his mouth every time I see him almost while we wuz there.

Well, to resoom backwards a little. Josiah come in in about haif an hour. The mair had started back straight for home. That mair has a constant heart under her white hide, and she’d left children there and grandchildren, I didn’t blame the mair, though I pitied my poor Josiah, he wuz beat out. He said that if it hadn’t been for Tom Willis he never should have ketched her at all. But that didn’t surprise me any, for Tom Willis is one of the kind who always will find a way to do anything he sets out to. So he had helped Josiah ketch the mair.

They wuz dretful glad to have us there, it had been more than a year since we had been there to stay any, and now we laid out to stay two days and nights, and they wuz tickled. But as glad as they’d been to see us, when that long, slim feller come walkin’ in, if you’ll believe it, Tamer Ann Allen actually seemed gladder to see him and made more on him than she did of Josiah and me, it wuz a sight to see it go on.

It seemed that when that old young chap come down into that neighborhood he put up to the hotel to Zoar, and then would walk over to Hamenses, and be there day in and day out, and stay jest as long as he could. He liked Anna as well as he could like anything outside of his old bones and ancestors and things, and I didn’t wonder at it, for her fresh young beauty must have been attractive to him, and a sort of a welcome change from his own looks and dry bones and family trees and such.

But I see she didn’t care anything about him, and I didn’t blame her; good land! I thought to myself I could easier git up a sentimental attachment to a good new telegraph pole, for that would be kinder fresh and hemlocky. But Tamer bowed down before him as if he wuz pure gold. His name wuz Von Winklstein Von Crankerstone, or I guess that’s it. I can’t be sure even to this late day that I have got the name down right, all the Vons and Winkles and things in their right places. But I have done the best I could, and no man or woman can do more.

Tamer didn’t like it, because I couldn’t git his name right when she introduced him, and I guess I did stumble round considerable amongst them Dutch syllables. But Tamer didn’t like it, for in apology for my shortcomin’s I mentioned Dutch. And she sez out in the back kitchen, where I followed her, to apologize:

“You speak of his bein’ Dutch; why,” sez she, “Josiah Allen’s wife, he is from one of the oldest families in the country, he is a descendant of the Poltroons who settled on the Hudson in Colonial days.”

“Is that so, Tamer?” sez I. “And is a Poltroon any better for bein’ a old one than a young one?”

And she sez, “I didn’t say Poltroon.” And she went on to explain, but it wuz sunthin’ that sounded jest like it. Well, he stayed till after dinner, and then he went off, much to Anna’s relief, I could see plain. But Tamer acted real disappointed, and urged him warm to come agin soon, which he promised to do ready enough. He wuz comin’ back the next week, I believe; he had found some new old graves somewhere that he wanted to identify and claim, if possible. It beats all how fond he wuz of cemeteries. But, then, he had a good deal the look of a tall slim monument himself.

He bid us all good-by in a real polite way, but agin, when I tried to speak his name in farewell, I struggled round and fell helpless amongst the ruins of them syllables.

Why, it beats all the time I had with ’em, and to eppisode forward a little. A few weeks afterwards, when the Poltroon wuz there on another visit, they wuz to our house to tea. He wanted to look in the Jonesville cemetery, so they stopped to our house on their way back. And Thomas J. and his folks, and Tom Willis and Elder Minkley all happened to be spendin’ the afternoon there, and I shall never forgit the names I called that Poltroon trying to introduce him. Why, I called him by more than forty different names, I’ll bet; I strugglin’ and wrestlin’ as you may say among the Vons and Crinkles and etcetery, tryin’ hard to do my very best by him and the other visitors and myself.

And that decided me; I toilin’ and prespirin’ and sweatin’ in my efforts to git the syllables all straight in a row and drive ’em on in front of me, and he standin’ lookin’ like a martyr. He bore up under it wonderful, I must say that for him, lookin’ bad but speechless. It wuz jest after that last effort of mine to git the name jest right (for I wuz introducin’ him to Elder Minkley, and I always try to do my best by ministers, good creeters, they deserve it), that I wunked Tamer Ann out, she lookin’ mad, and I red and prespirin’ with my efforts, and, sez I, “This must end, Tamer Ann.”

And sez she, “I should think as much!”

“Well,” sez I, “Von Crank or Von Wink is what that young man will be called by me for the rest of my days.”

She demurred, but I stood firm. Sez I, “I may have to speak his name several times while I live, and life is too short for me to go stumblin’ round amongst the syllables of his name and wrastlin’ and bein’ throwed by ’em. Von Crank is my choice, but you may take your pick in the two names.”

She see I wuz firm as adamantine rock, and so she yielded, and Von Crank is what I’ve called him ever since. Tom Willis acted tickled, and so did Thomas J. Thomas J. sets a sight by Tom Willis, and so we all do. He is a likely young feller, light complected, with blue-gray eyes that are keen and flashin’, and soft at the same time, and no beard, only a mustache; a tall, broad-shouldered young chap. And as I say he wuz tickled to see Von Crank stand up straight and stiff and immovable genteel, and I callin’ him by so many awful names and knowin’ by my firm stiddy mean I wuz doin’ my very best by him and myself and the world at large.

It hain’t nateral under the circumstances that Tom should love Von Crank or Von Crank love him. They hain’t attached to each other at all, anybody could see that at the most casual glance. To see Von Crank try to patronize Tom and couldn’t, and to see Tom say the dryest, provokinest things to Von Crank in a polite way and Von Crank writhin’ under ’em, but too genteel to say anything back. It wuz a strange seen. And to see Anna by all her lovin’ looks dotin’ on Tom, and Tom’s silent, stiddy devotion to her, and Tamer Ann’s efforts to git ’em apart and still keep genteel—why, it wuz as good as any performance that wuz ever performed in a circus, and so I told Josiah afterwards.

Tom tried hard to act manly and upright, and that always effects me powerful. To see a young man blowed on by such blasts of passion, such a overmasterin’ love and longin’, and still standin’ up straight and not gittin’ blowed over by ’em, it always affects me, I can’t help it, I wuz made in jest that way.

Now, after Von Crank got to goin’ after Anna, Tamer Ann, as I said before, told Tom Willis to never step his foot in her house agin, and have nothin’ to do at all with Anna.

Well, Tom bowed to her, they say, and took his hat right up and left without a word back to her only “good mornin’,” it wuz in the mornin’ time that she told him. But they say, and I believe it, that his face wuz white as death, even to the lips, and they wuz tremblin’, so they say. And mebby he couldn’t say anything owin’ to the sinkin’ of his heart, and mebby it wuz because he wouldn’t promise to give her up and didn’t want to mad Tamer Ann by contendin’ with her. Anyway, they say he didn’t say nothin’ only jest “good mornin’,” and went out.

He might have said enough. Good land! if I had been there I could have told him lots of things to say.

He might have said, “It is pretty late in the day to ask me to give her up when she is right inside my heart and soul, and I should have to tear ’em both open to git her out. It is pretty late in the day to interfere when you have seen Anna and I playmates from childhood. When you’ve seen us grow up side by side, all through our happy youth to manhood and womanhood. When you’ve encouraged us to be together at all times and all places, trusted her to my care hundreds and hundreds of times all these years. Have looked on calmly and seen, for you must have seen, how our hearts wuz growing together, how our lives wuz gittin’ completely bound up in one another. After you have sot quietly and allowed all this, now because a richer, more fashionable suitor asks for Anna you think you will take her away from me, from the one that holds her by the divine right of love, and give her to one she does not belong to. It shows either a criminal carelessness on your part, a criminal neglect, or worse.”

That’s about the way I should have talked if I had been Tom Willis. But he didn’t, he jest walked out and shet the door, not slammin’ it, or nothin’, and—and kep’ right on livin’. Never made no threats about killin’ himself, never boasted, as might be spozed he would, it is so common under the same circumstances, that he had got sick of her, and, in fact, wuz so popular among the wimmen that he had to slight some on ’em now and then, no, Tom never said anything of all this, but jest kep’ right on with his work in a manly, stiddy way, growin’ kinder pale and still for a spell, but at last sort o’ brightenin’ up and havin’ a new and steadfaster light in his eyes, and a more resolved look on his fine forward.

He see Anna every Sunday in church, and, though he obeyed her mother and didn’t give her any outward attention, yet there is a stiddy attention of the soul that a woman can’t misunderstand when it is wroppin’ her completely round and round. There is a language of the eyes beyend Tamer Ann Smith to parse; it wuzn’t in her grammar at all. And if she couldn’t parse it, it wuzn’t likely that she could stop it. No, she might as well try to stop the vivid language of the skies when the hidden forces of nature speaks out in sheets of flame.

Tom’s eyes, as they met Anna’s in the old meetin’ house, held hull love poems, glowin’ stories of deathless devotion and faith in her. And Anna read ’em, she alone held the key to the divine unwritten language; the love in her own heart could alone translate the love in his.

Well, it had run along so for more than a year, and Anna wuz twenty and Tom wuz twenty-three; Tom workin’ hard and beginnin’ to be spoke of as a young lawyer who would rise in the world. And Anna stayin’ to home and tryin’ to be dutiful (duty made hard by naggin’). Havin’ to use Von Crank well under her mother’s eyes and freezin’ him in lonely moments, froze one minute by Anna and thawed out the next by Tamer Ann, and kep’ kinder soft and sloshy all the time by his love for Anna, Von Crank wuzn’t to be envied much more than Tom.

But Tamer Ann (for he had acted up to his high station as a Poltroon, and kinder relied on Tamer Ann to bring Anna round when he knew in his heart that she detested him) kep’ tellin’ him all the time that she would be all right in time, it wuz only a girl’s shyness, etc., etc. So he kep’ on comin’, and Anna kep’ on shunnin’ him all she could, and Tamer Ann kep’ on naggin’, and so it went on. Hamen and John didn’t seem to pay so much attention to this domestic side show, for all their leisure moments, when they wuz in the house, would be took up foolin’ Jack, tellin’ him strange stories, drawin’ him on to talk strange about ’em, and then laughin’ at him. And Jack would meach off, feelin’ all used up and humiliated, and they snickerin’, the fools! There wuz more sense in Jack’s little finger than in their hull long bodies, and so I told Josiah.

Oh, how it incensed me to see it, and the incense grew stronger every time I went there. Tamer Ann had got holt of a hull chest of old dime novels that had fell to her from a distant relative. He wuz jest sent to prison, bein’ a forger and a arson, and, as it wuz for life, why this chest fell onto his relations, and as the rest didn’t want the novels, why Tamer Ann got ’em.

This relation who owned ’em had had a large family who doted on the novels, but they had most on ’em been transported for life or hung, or sunthin’ of that sort. His wife had long before run away with another man, she had worshipped the novels while she lived in the house with ’em, but she had run clear away out of sight, so Tamer Ann got ’em, as I say, and oh! how she and Cicero gloated over ’em and devoured ’em. Anna didn’t care for them, good land! she had a romance in her own heart that took up all her time and tears, poor thing! Jack wuzn’t old enough for ’em. As for Hamen and his brother, they could tell their own lies, good land! they didn’t need the novels, so Tamer had the hull run on ’em herself, she and Cicero.