CHAPTER X

Little Delight burnt up the world a week ago last Wednesday, somewhere along about the middle of the forenoon.

She stayed here three days and four nights, while her Pa and Ma went to North Scriba to his folkses on a visit. Diphtheria wuz ragin’ there among the little children, and we none of us wuz willin’ to let Delight go. And they thought that they must go, for Barzilly Minkley, who hadn’t been in this part of the country for years and years, had come home to his folkses on a visit (Barzilly is Whitfield’s own cousin on his father’s side), and all the Minkleys wuz invited to the old Minkley homestead to visit with him.

Whitfield wanted to go, but didn’t want to unless Tirzah Ann went. I approved of their goin’, and told Tirzah Ann I would help her all I could. I helped her make a new cashmere dress and a blue wool travelin’ dress, and told her she could wear my new waterproof in welcome, hern wuz a old one. And I told her I would take care of little Delight and take it as a privelige. So they started early on a Tuesday mornin’, and we went after the child Monday night, so’s not to belate ’em on their journey. And it wuz on the Wednesday follerin’ about ten o’clock in the forenoon that she burnt up the world.

She wuz dretful willin’ to come home with us, and we wuz dretful willin’ she should come, which made it willin’ all round, and agreeable. She thinks as much of Josiah and me as she duz of her Pa and Ma. And I made her a bed on the lounge in our room, and it did seem good to have her there. We took sights of comfort.

Her little appetite wuz excellent, and it wuz a great comfort to me to cook things she called for. I can tell you it brought back old times when her Ma and uncle, Thomas J., wuz little children, every time I baked turnovers for her. And when I fried cakes it did seem so good to fry men and wimmen and children and every livin’ animal I could think on for her. And it seemed as if I couldn’t hardly satisfy her on the animals. I do believe I fried every critter I ever hearn on, unless it wuz a hyena, and it kinder seems as if I fried one of them one day, but I won’t say for certain, maybe it wuz a catamount, they look some alike, anyway.

But we did enjoy havin’ her there the best that ever wuz. When she got up in the mornin’ and come to us with her great bright eyes dancin’, and the mornin’ light shinin’ on her wavin’ hair, it almost seemed as if it wuz our lost youth comin’ back towards us with immortal hope and gladness in its glances. We loved her so, she wuz so much a part of our own hearts and lives that it seemed as if our love for her and our tender pride and happiness in her, carried us back into the Long Ago. And we could almost fancy she wuz one of our youthful dreams gin back to us and made real.

Oh, we took sights and sights of comfort with her, I don’t think we love her any better than we did her Ma and Uncle, Thomas J., I know we don’t, and I don’t think the neighbors are doin’ right when they say we do. And I think it is very unkind and unreasonable of ’em to say that we humor her to death and make a perfect fool of her. It is not so.

But we have more time to spend with her than we did with our children when they wuz little. Then we had to work hard to git along and pay for the place. And Josiah didn’t have no time to take Tirzah Ann or Thomas J. onto the plough handle in front of him and let ’em ride round the field with him, and etcetery. And I didn’t have time to stop sweepin’ and washin’ dishes and let ’em play they wuz washin’ dishes and sweepin’, and so forth and so on.

And we didn’t have time, Josiah and me, to let ’em take holt of our hands, one of us on each side of ’em, like the Babes in the Woods, and lead us all over jest where they wuz a mind to—into the woodshed and all over the dooryard, and the barn. But now when Delight is here we are jest the Babes, Josiah and me, to be led off anywhere she wants to lead us.

For things are different now. The farm is paid for, the children are brung up, and well brung up (everybody admits that). And if little Delight wants to lead round her Grandpa and me she is goin’ to lead us, and there hain’t nobody goin’ to break it up. Good land! we enjoy it as much as she duz. And if she should take it into her little head to lead us off into the woods and cover us up with leaves, it wouldn’t be any of the neighbor’s bizness, if Josiah and me wuz willin’ to be led and covered, as we most probable should be.

I think it is very unkind of the neighbors to say we let her have her own way all of the time, and don’t correct her at all. It is not anyways likely it is so, but spozen it wuz, if her way wuz the right way why not let her have it?

It’s very seldom that she duz a thing that is the least mite out of the way. I don’t know that I could exactly approve of her burnin’ up the world—that might not been exactly the fair thing to do, but it is very, very seldom she duz a thing a minister would be ashamed of doing. She is a oncommon child for goodness. I don’t say it because she is my grandchild, not at all. But truth will out. She has a remarkable sweet, even disposition, and as to morals—well! I would like to see the child that would go ahead of her in morals. Why, we couldn’t tempt her to touch a penny that didn’t belong to her. And burglary, or arson, or rapine, why, nothin’ would tempt her into it. She is a wonderful child.

And she is jest as truthful as the day is long, that is, what she calls truth. Everything is new to her and strange. The thoughts in her little brain jest wakin’ up, and to a imaginative child the dreams and fancies that fill her little mind, the child’s world within, must seem as strange as the new strange things of the world about her.

It is all a untried mystery to her, and it stands to reason that she can’t separate things all to once and put the right names to ’em all. The gay romances of the child’s fairy world within from the colder reasonin’ of the world without. The child’s world is purer than ourn, it is the only land of innocence and truth we know in this dreary life. And it seems as if we would let our souls listen to catch any whispers from that land, so sweet, so evanescent.

For there is the only perfect faith, unbounded, uncalculating, so soon to be displaced by doubt. The only perfect innocence, the blessed ignorance of wrong, so soon, so surely to be stained by the knowledge of sin. The divine faith in other’s goodness so soon to be dimmed by distrust. The gay, onthinkin’ happiness, so soon to be darkened by sorrow and anxiety—the rosy hopes so soon to fade away to the gray ashes of disappointment. Fair land! sunny time! so bright, so fleetin’—it seems as if we should treat its broken language, its strange fancies tenderly and reverently, rememberin’ the lost time when we, too, were wandering in its enchanted gardens. Rememberin’ that the gate of death must swing back before we can again enter a world of such purity, such beauty.

But we do not, we meet its pure and sweet unwisdom with our grim, rebukin’ knowledge which we gained as Eve did, its innocent, guileless ways with the intolerance of our dry old customs, its broken fancies, its sweet romancin’ with cold derision or the cruelty of punishment. It makes me fairly out of patience to think on’t.

It stands to reason, when everything under the sun is new and strange to ’em, they can’t git all to once the meanin’ of every big word in the Dictionary, and mebby they will git things a little mixed sometimes. But how can they help it? Why, what if we should be dropped right down into a strange country where we had never sot our feet before and told to walk straight, and wuz punished every time we meandered, when we didn’t know a step before us, or on each side on us, how could we help meanderin’ a little, how could we help sometimes talkin’ about the inhabitants of the world we wuz accustomed to, usin’ its language?

What we would need would be to be sot in the right way agin, with patience, and over and over agin, and time and time agin. Patience and long sufferin’ and reason is what we should need, and not punishment, and that is what children need.

Many a child is skairt and whipped into bein’ a hippocrite and liar, when, if they had been encouraged to tell the truth—own up their little faults and meanderin’s—and treated justly, patiently, and kindly, they would have been as truthful and transparent as rain water. Children have sharp eyes and are quick to see injustice, and things sink deep into their little souls. They are whipped if they don’t tell the truth, skaired dark nights with the lurid passage—“Liars shall have their portion in the lake of fire and brimstone.”

And then they see their mother smile into some disagreeable visitor’s face and groan at her back. How can the baby wisdom part the smile from the groan, and find truth under ’em? How can we? They are taught under fear of severest punishment to be honest—“Thou shalt not steal.” And then, with their earliest knowledge, they hear their mother boast of some advantage she has gained over the shopkeeper, and their father congratulating himself on how he got the better of his neighbor in a horse trade. And if she be the child of a business man, happy for her if she does not wonder at that sight strange to men and gods, to see her father lose all his wealth one day, to rise up rich the next, rise up from a crowd of poor men and wimmen he has cheated and ruined.

She is taught that deceit is an abomination to the Lord. And then she stands with her little eyes on a level with the washstand, and sees her big sister paint and powder her face, darken her eyebrows, and pad her lean form into roundness. She is taught the exceeding sinfulness of envy, strife, and emulation. And then, in the same breath, urged to commit to memory more Bible verses than little Molly Smith has learned, and consulted about the number of ruffles on her dress with the firm resolve to have one more than she has, so as to be cleverer and look dressier than she duz.

She is taught that God loves good children, and to flee from evil communications, and then counseled to never by any means associate with the washerwoman’s little girl, who is very good, but to play with the banker’s little boy, who is very bad.

She is taught by precept to be studious, industrious, and that Heaven smiles on contented labor, and industry and independence are honorable and to be desired, she hears her mother say solemnly, “Wealth is a snare.” And then she sees that mother bow low at the feet of the rich, stupid, idle wife of the millionaire, lose all her dignity and self-respect in the wild effort to become her friend, sees her refuse to recognize in public the honest, intelligent sewing girl.

She is taught that if she duz not learn the catechism and follow its teachings, she is lost indeed, and she learns from that that the chief end of man (and presumably wimmen) is to fear God and enjoy Him forever. And then taught by the louder teaching of maternal anxiety and counsel that the chief end of wimmen is to be married, to get an establishment and a rich husband to support her. How is the child to learn good from evil? God help the dear little souls! and if they keep one iota of the sweet, oncalculatin’ trust, the divine innocence of childhood, it is by the direct grace of God, and no thanks to the poor worldlings and sinners by whom they are surrounded.

Amongst the marvelous wonders of God’s universe to me one of the greatest mysteries is this, how a good God, a just, pitiful God, should send into such hands as He duz such little white souls.

Some frivolous young girl, whose highest thought and ambition has never soared above her hair ribbon, some brainless boy, whose deepest desire and highest aim has been to wear as small a boot as he could, and contract hopeless debts for hair oil and cheap cigars and whiskey. In some unhappy season, when circuses were not possible, and wishing for a kindred excitement, they rush into matrimony. And into these hands, joined by lowest links, these hands defiled by sin, and weak with the utter weakness of unreasonin’ selfishness and folly, is sent a little pure soul out of Paradise.

And this little child must grope in the dark shadows caused by the denseness of their ignorance. Suffer forever physically, morally, mentally from the evil, the total depravity of their hereditary and teachings. Suffer herself and grow up in the black shadow to transmit its hopeless darkness and guilt down to other generations. Strange, strange, most marvelous of mysteries, why this should be so. But I can’t bear to even look on this dretful picture even in hours of eppisodin’, it is bad enough and strange enough to look in Christian homes, amongst meetin’ house brothers and sisters, and see how the little ones are maltreated.

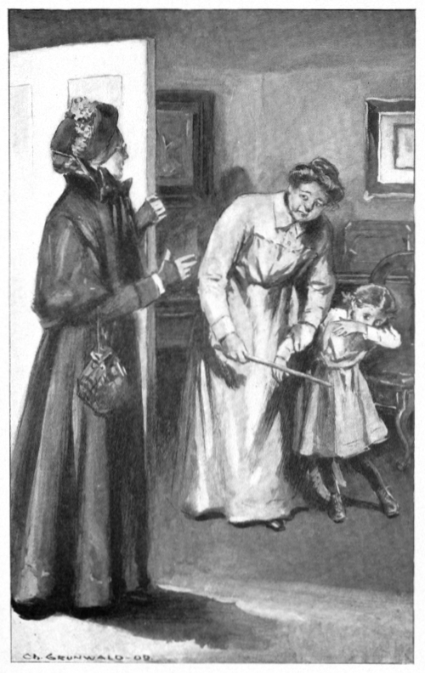

It looks dretful disagreeable to me, to see a young child whipped for what we do ourselves. Now, I wuz at one of our neighbors’ the other day (one of them that complains the most of our treatment of little Delight), and she has got a young child of her own, some four, or half-past four years of age. And when I went in she wuz whippin’ little Kate with a stick, her face all swelled up with what she called religious principle (I called it anger), but, howsumever, it hain’t no matter what the name on’t wuz, her face wuz all red and inflamed. And she, weighin’ from two to three hundred pounds, wuz standin’ over that little mite of humanity, that she herself brought into the world, for better or worse, stood over it, grippin’ with one hard, red hand the little tender arm, leavin’ great red marks with her voyalence, and layin’ on the stick with the other, for she said she had lied.

SHE WUZ WHIPPIN’ LITTLE KATE, HER FACE ALL SWELLED UP WITH WHAT SHE CALLED RELIGIOUS PRINCIPLE.

“And lyin’,” sez she, with her face redder than ever with what she called principle (and I called madness and revenge), “is sunthin’ I won’t have goin’ on in this house!”

Sez I calmly, for I see it wuzn’t my place to interfere, “What has she been lyin’ about?” And she said she had told her to not stay but a hour to Miss Bobbettses playin’ with her little girl, and she had stayed two, had lied about it. She had promised to come back in a hour and didn’t. “She said she forgot all about the time, till the two hours wuz up, and I know she didn’t forgit!”

Sez I, “How do you know she didn’t forgit?”

“Why,” sez she, “how could she forgit when there wuz a clock right in the room? She didn’t come back because she wanted to stay, and she must own it up to me!”

“But,” sez I calmly, “if the child did forgit you are whippin’ her into lyin’ instead of out of it.” I didn’t say no more, for I never interfere, and she took her out into the back room and finished up there, and I heard Kate own up that she had stayed three hours and meant to, and wuz sorry.

And then her mother had to whip her agin because she had owned up too much; finally she got her to own jest enough, and then Miss Gowdey come back into the room triumphant and happy and give the child a big piece of cake and jell. She said she always give the child sunthin’ nice when she owned up to tellin’ a story. And so she felt real good natered to think she had come off conqueror. And we had a good visit.

My bizness there wuz to ask her in a friendly way if she didn’t want to run in with me to see Miss Patten. Miss Patten had got a young child, and we hadn’t either on us seen it. And she said in a agreeable way that she would, and she told her husband when we went out she shouldn’t be gone only “jest an hour,” and told him to hang on the teakettle at five, and she would be there to help set the table. And she told little Kate to look at the clock, and when the pinter stood at jest five her Ma would certain sure be there. Well, Miss Patten wuz dretful agreeable, and so wuz Sam, that is her husband, and so wuz old Miss Patten, who wuz there takin’ care of Susan. And nothin’ to do but we had got to take our things off and stay to supper. We hung back, for we had told our companions we would be home to git supper in good season.

Sez I, “I don’t like to disappoint Josiah.”

“And I can’t disappoint my folks,” sez Miss Gowdey.

“Oh, well,” sez old Miss Patten, “if they go through the world without meetin’ a worse disappointment than that, I guess they’ll git along. They can eat their suppers a little later.”

“Oh,” sez I, “there is everything cooked in the house, all Josiah would have to do would be to make a cup of tea.”

And sez Miss Gowdey, “I have got everything all ready for supper, and Mr. Gowdey can make a better cup of tea any day than I can, he puts it in by the handful, he never uses a teaspoon.”

“Then do stay!” sez Susan.

And sez old Miss Patten, comin’ in from the kitchen (Nabby wuz sick in the settin’ room bedroom), “you needn’t say another word, the table is all sot for you. We have got stewed oysters and warm biscuits and honey, and you have got to stay.”

And she took our bunnets right off and galanted us into the dinin’ room, and we did have a splendid supper. And there it wuz—we two wimmen, both on us weighin’ most two hundred, and with half a century’s experience—there we wuz doin’ jest what Miss Gowdey had whipped little Kate for. That delicate creeter with her little mite of judgment and her easiness to be led astray, and not weighin’ over forty pounds. Well, the supper sort o’ took up our minds, and we set at the table a good long while. And we didn’t want to start off the minute we got through eatin’. But I did feel strange in my mind thinkin’ it over, and, though they wuz dretful agreeable, I sot round in my chair and looked at the clock, and Miss Gowdey turned round and looked, and sez she:

“Good land! if it hain’t eight o’clock. What will our folks say?”

And sez I, “What will Josiah say?” And we started home a pretty good jog. And Miss Gowdey sez, when we had got most to her house:

“For the land’s sake! if we hain’t stayed away three hours.”

And sez I in a cursory way, for I will not hint or meddle, “You whipped little Kate for staying one hour beyend her time, and we have stayed three.”

“Well,” sez she, “I told her to be home in an hour.”

“That is jest what she told you to do,” sez I.

“And,” sez she, “she promised.”

“So did you promise sacred.”

Sez she, “A child is under greater obligations to her parents than the parents are to her.”

“I think they hain’t under half so much obligations, for it is the parents doin’s gittin’ ’em here, the children didn’t git the parents here, it is right the other way.”

“Oh, well, it is different, anyway. Kate is a child, and we are grown folks.”

“So much more the reason for us that we should behave ourselves and not go to lyin’ and bein’ led off into temptation as we have to-night, Sister Gowdey. We are both Methodists.”

The words sunk deep, I see they did, though she only sez:

“I do hope Mr. Gowdey hain’t got supper, a man tears up things so and wastes. I would as soon have a tornado sweep through my buttery as to have a man sweep through it.”