CHAPTER XV.

Tamer and Jack stayed all night, and the next day but one we wuz all to meet at Thomas Jefferson’s, and then she wuz goin’ home and leave Jack with me for a week or so. The prospect wuz very pleasin’ to Jack and me, and to Delight, for she wuz going to stay too. The next day, bein’ we wuz alone together, except the children, it seemed as if Tamer wuz just crazy to onburden her heart to me about her trouble in makin’ Anne listen to what she called reason and marry Von Crank, and the ingratitude of a child’s disobeyin’ her parents, and the imprudence and recklessness of her love for a poor young man. And of course, seein’ she wuz a visitor, I had to set and hear the talk dribble on. Why, the idee of punishin’ Jack for talkin’ about marriage when he didn’t hear anything else when he wuz in the house.

I let it go on, thinkin’ I had said all I could on the subject. But at last, for wimmen’s patience can’t hold out only jest so long, she promulgated the idee that she thought that she should send Anne to the Convent of the Holy Heart; sez she, “She can learn some accomplishments there of the Sisters that she can’t anywhere else. But,” sez she confidentially, “the real reason I am doing it is to separate her from Tom Willis, for if I could once git her mind off from him I believe I could make her marry the man I want her to.”

Sez I coolly, “I would choose a place with some other name.”

“What do you mean?” sez she.

Sez I, “I would never choose a place called the Holy Heart for such a heartless affair as you are goin’ into.”

“Heartless?” sez she.

“Yes,” sez I calmly, turnin’ Josiah’s second best vest over and attacktin’ it on the other side (I wuz patchin’ it), “under the shadow of the Holy Heart with His name printed above you you want to desecrate and ravage a heart, sell a heart. There wuz a time when your child’s heart wuz a smooth, ontroubled place, a page with nothin’ writ down on it but domestic names and attachments. Then wuz the time for you to have guarded that white, still place. If you hadn’t wanted Tom Willis to write his name there on the virgin whiteness of that heart why did you let ’em be together day by day and year in and year out? You kep’ still, readin’ your dime novels and discoverin’ your new diseases, of which I dare say you have a variety,” sez I (for I see she looked mad), “you kep’ still and never said a word of warnin’ or command, or disapproval, left them two young hearts jest prepared for their images to be photographed on each other by the divine photography of the Sun of Love, and now when their images are stamped so full and onfadingly that no earthly hand can rub ’em out, now you complain of the imprudence of young people, the recklessness with which they form attachments and the wickedness of it.

“But, Tamer Ann Smith, I tell you now that what you call the imprudence and recklessness is not in Anna, but in her gardeens. Her gardeens that didn’t watch her young heart, her young, careless, springlike, girlish life, that wuz bound to burst into bloom when the sun shone on it. It wuz in your power mebby early in the mornin’ to have picked out the light for her, selected the sun, but after it is once riz and set the world to bloomin’ you can’t do it, you can’t stop the divine freshness, the bird’s song, the sadness, the glory, the pathos, and the power, the light that never wuz on sea or shore, you can’t put up any umbrell to shet off that light, and so I give you warnin’.”

Sez she, “I will do it. Anna shall never marry Tom Willis.”

“You’ve started late in the day to hender it.”

“I will hender it,” sez she.

“Well,” sez I calmly, “time will tell.” And to turn the subject round and please her at the same time, I sez, “How duz your basler mangetus seem to be to-day, and your sinevetus?”

But she wuzn’t to be turned round even by her favorite subject. Sez she, “You like Tom Willis, and you know it.”

Sez I, “I hain’t disputed it.”

“I believe you encourage Anna in thinkin’ of him.”

“Not a word has Anna heard me speak either for or aginst. There wuzn’t any need on’t,” sez I; “it would be too late for me to begin if I wanted to. No, I am simply settin’ still and seein’ things and circumstances pass before me, some as if I wuz settin’ on a bench at a circus.”

“If you wuz Anna’s true friend and mine, if you acted as a blood cousin ort to, you would talk to Anna and try to make her listen to reason.”

“No, I thank you, Tamer Ann; there is sunthin’ now in her heart that is beyend reason, as fur above and beyend it as the stars are above the earth.”

“If you did your duty, Josiah Allen’s wife, you would tell her to obey her mother and marry the man her mother approves of, that her mother’s superior wisdom and experience teaches her is the best fitted to insure her child’s happiness.”

“No, Tamer Ann Smith, I make no matches nor break none, and if I wuz goin’ to advise Anna, which I hain’t, I shouldn’t be liable to advise her to give up all the beauty and romance and happiness of life for the sake of settin’ down under the shade of a family tree and let it shade me alongside that walkin’ mummy, Von Crank.”

“One of the oldest and most aristocratick families in the State. You ought to take it as a great honor that he felt willin’ to connect himself with the Smith family at all.”

I see we couldn’t agree, and I sez, “Tamer Ann, you will agitate yourself so your baslar mangetis will be worse—man-get-us,” sez I thoughtfully; “if that wuz only a contagious disease I know lots of single wimmen who would love to have it prevail.” But my friendly joke didn’t turn her mind round as I meant it should; no, she went on bitterly:

“To think Tom Willis should think of marryin’ Anna, and his father only a common carpenter.”

“Well, Tamer Ann,” sez I, “we kneel every day of our life and worship One who wuz called that.

“Tom Willis,” sez I, “has got the wealth and distinction in himself instead of havin’ to put on a pair of magnifyin’ specks and try to trace it back to some remote ancestor, who mebby had a spark or two of it. You’ll find it right here in him, and I think it is better to have the nobility where you can put your hand on it in a handsome young form than to be chasin’ back for it up a family tree, climbin’ up mouldy old branches, follerin’ rotten, decayin’ old limbs, and some sound ones,” sez I, reasonable; “but, anyway, nobility a century or so old seems sort o’ shadowy and spectral, and don’t impress me so much as it duz while it is right before me, strugglin’ on through disappointments and pain, tryin’ to reach the high prizes of success and Anna—or, I mean, happiness.”

She tossted her head real kinder disdainful, but I went on, for I begun to feel eloquent: “It is so difficult to know a hero when you see him right before your face and eyes. It is easy now, after everything is passed, to open your encyclopedia and read the names of Columbus, and Washington, and Newton, and Luther, etc. But the time wuz when Columbus walked the streets unknown, all the fire of genius, the passion of the discoverer must have looked out of his sad eyes onto the onsympathetic faces of the crowd; it wuz all hidden in his soul. His ears heard the swash of new seas breakin’ on onknown shores, his eyes saw the tall mountains of a grander continent risin’ through the mists, but them around couldn’t see it, they wuz down there in the mists and stayed there. The discoverer of a new world walked homeless and friendless through the streets. He couldn’t carry them cold, blind eyes into the glorious possibilities of the future. No, the poor blind eyes looked scornful at him and laughed at his hopes. The great philosophers and inventors who apprehended what they couldn’t comprehend; who looked through the summer skies cleft by the fall of an apple and saw great systems of philosophy; who saw by the steam of a tea kettle a whole world bound together by swift-rollin’ wheels of lightnin’ speed; who saw through the child’s kite the continents talkin’ together—their rapt eyes saw all these glorious possibilities and wuz derided for it and called idiots by them who looked down on ’em and told ’em it wuz folly, idiocy of the deepest degree to see anything in the fallin’ apple beyond the possibility of a pie. This is the same kind of worldly common sense that makes us onmindful every day of our life of the presence of real heroes in our midst who, manly, honest, and God-fearin’, are tryin’ to vanquish the ills of life and conquer success.”

“I spoze you think Tom Willis is one of them heroes,” sez Tamer coldly, cold as a ice-suckle.

“Yes, seein’ you’ve asked, I’ll tell you plain I do think so, and I lay out to look on him now with the same pair of eyes I would when he got his name writ down on the pillow of fame; he needs my sympathy now—he wouldn’t then, if I wuz livin’ to give it to him. It would be a good thing for these heroes and for our own souls if we put a few of the flowers we put on the monuments of dead heroes into the empty hands, the poor, tired, scarred hands of our live heroes to-day. If a few of the smiles and hurrahs we keep for onanswerin’ eyes and ears was spent on our live heroes who are fightin’ life’s battles jest as General Grant fought his, straight on the line, with no manoovers or false movements, straightforward and simple and manly——”

“You are thinkin’ of Tom Willis agin,” sez Tamer Ann sarcastickally.

“Yes, I am,” sez I firmly. “Tom Willis has got genius, perseverance, good common sense and a lovin’ heart, and that is jest the stuff heroes are made of. Genius alone is flighty and takes a man offen his feet, swingin’ him up above the housetops; common sense alone is too heavy, weightin’ a chap down; but take both together, with perseverin’ industry and a lovin’ heart, they will take a boy right straight towards a monument, and that is jest where Tom Willis is goin’. He is goin’ away from the jealous eyes and persecutions and tribulations; whether we help or hender, he is bound for a newer, grander country, a prosperous future where he will cast anchor bimeby; his sails are sot for it, he will git to it, and whether he carries into it a happy or a achin’ heart depends on you, Tamer Ann Smith.”

“Oh, shaw!” sez she.

Sez I mildly, “Shawin’ never did any good in the past, Tamer Ann, nor I have no reason to think it will in the future.”

Nor any hurt, I sez to myself reasonable, for I had faith to think that it would all come out right in the end, dark as it looked now, for Anna wouldn’t marry without her ma’s consent, and it looked like obtaining sweet milk from a soapstun to git a consent from Tamer Ann. But I kep’ my faith, and would say to myself time and agin, Hain’t it as big as a mustard seed? Can’t I git up faith as big as a pinhead? I ort to, and then I would try.

That very day, whilst Tamer and I wuz visitin’, word come that her mother on her own side wuz took away with a fit and the funeral wuz to be to the house next day but one.

Hamen’s wife felt quite bad, she shed a number of tears that I see, and mebby some I didn’t see, I shouldn’t wonder, for a mother is a mother as long as her skin and bones hold her heart. Of course for years Ma Bodley had been failin’ and runnin’ down, but watched over good by Tamer’s old maid sister, Alzina.

She wuzn’t quite so noble a Christian old maid as the one who took care of Anna’s childhood, but she wuz a good, faithful creeter, and the best judge of mustard plasters and milk porridge I ever see—well, she’d handled ’em enough to be a judge of ’em. Hamenses wife went right on to her old home with the man who come to tell the news, and Josiah and I told her we would come to the funeral. It wuz goin’ to be to the house, and as their house wuz liable to be full of relations I told her to leave Jack and I would bring him with me.

We wuz goin’ to stop and leave Delight to home on the way to the funeral. Well, no sooner had they started off than Jack tackled me about the funeral—what funerals wuz, and what they did to ’em. And I went on and explained it all out to him as well as I could, and when I come to tell him about the hearse, for I talked quite diffuse, partly to get his mind off, he said he should ride in it.

I argued with him for a spell, but he stood firm to the last that he should “ride in that hearse.” I told him it wuz for his poor Grandma. And he said there wuz room enough for both; she had always divided everything with him. And he cried a little—he loved his Grandma. And he wanted to know if his Grandma couldn’t talk and tell him about dyin’, what it wuz. He said Grandma would always answer questions.

And I sez, “Grandma can’t answer this question, Jack.” And then I tried to explain it to him as well as I could how part of Grandma, the best part, her life and soul, had gone up into heaven, and he would find it there some day. Tegus wuz the questions he put to me, but I buckled on my boddist waist of duty and tried to answer ’em, and he went to bed quite clever.

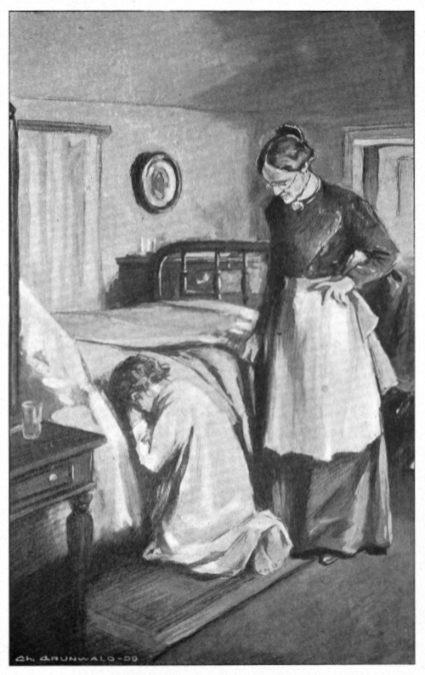

I went up into the room and helped him ondress and hearn him tell his prayers, and tucked him up and left him with a warm good-night kiss and went below to git Delight ready for bed. And, oh, how sweet she did look as she knelt in her little white nightgown, her dimpled hands clasped on my knee, and her great, big, innocent eyes lookin’ up into my face and through it, searchin’ for the Eternal Good she was addressin’! I wuz waitin’ to hear her commence, my Josiah lookin’ on admirin’ly from the other side of the hearth. When all of a sudden she broke out, all of a sudden like, and, sez she:

“Oh, before I forgit it, Lord, I want to tell you.”

Josiah made a horrified exclamation as if he wuz shocked beyond all account, and would have stopped her. But I gin him a warnin’ look and let her go on. “Before I say my prayers, dear Lord, I want to tell you that I wuz a selfish little girl yesterday morning, and I want you to help me; I want you to help me special to be a generous little girl, and I will help you, too, or mebby I won’t.”

I WENT UP INTO THE ROOM AND HELPED HIM ONDRESS, AND HEARN HIM TELL HIS PRAYERS.

Here Josiah fairly throwed up his hands and sez, “Samantha Allen, this is goin’ too fur; I won’t set still and see irreverence goin’ on in my house. She must not be allowed to say such things. I speak as a deacon,” sez he, lookin’ some big. And it wuz to think on a dretful speech to make, tellin’ the Lord that mebby she would help Him and mebby she wouldn’t. It sounded strange and bad, and if I had hushed her up and rebuked her chillin’ly we should always thought she wuz irreverent and irreligious; but I felt that there wuz sunthin’ to the bottom of it more than she could with her small stock of language readily make known. And I gin my pardner a deep look as much as to say, “Keep still, Josiah Allen,” and then I bent over Delight and sez:

“What do you mean, Delight, by sayin’ mebby I won’t? That don’t sound jest right, sweetheart; you know you are talkin’ to the One Highest and Best, who made you and keeps you alive and who loves you better even than grandma duz. You must be very true and lovin’ and humble when you talk to Him.”

“Well, that is what I mean. If I told a wrong story to you it wouldn’t be so bad as if I told it to God, would it?”

“No, I don’t know that it would,” sez I candidly.

“Well, I wuz so ’fraid I would tell one to Him if I said right out I would help Him.”

And I sez gently, “Tell me all about it, Delight.”

“Well, yesterday mornin’ I took the biggest pear on the table, and papa said I wuz gettin’ to be a selfish little girl, and he felt bad about it. I told him I would tell the Lord all about it, and I guessed He would make me better. I said I would ask him special to, and I would help Him. But I forgot to ask Him last night, and I thought mebby I would forgit and do something jest as bad, and that would be tellin’ a wrong story to the Lord, wouldn’t it? And so I thought I would say p’rhaps I wouldn’t, so He wouldn’t be sprized if I forgot and wuzn’t jest good, don’t you see?”

“Yes,” sez I, “Grandma sees jest how it wuz,” and I cast a triumphant look onto my pardner, but he, too, wuz lookin’ perfectly happy and contented, and so Delight told her little prayers, “Our Father,” and “Now I lay me,” and ended up with:

“God bless Papa and Mama, and Grandma and Grandpa, and Uncle Tom and Aunt Maggie, and little Snow, and don’t forgit, please, please, please, dear Lord, to make me good, and don’t let me forgit it, and don’t let me forgit I want to be good when I git to playin’ with Jack and he plagues me, and bless Jack, amen.”

And I took her in my arms and put her to bed after I had held her down to kiss her Grandpa, bless her sweet face! I laid her in her little crib and kissed her more’n a dozen times, and she me; and when I went back into the settin’ room I sez to Josiah, “If there wuz ever a deep religious prayer, that wuz.”

“Yes,” sez he; “it wuz a prayer any minister might be proud on.”

“To think,” sez I, “of her bein’ so conscientious, so ’fraid of lyin’ to the Lord; and think of all the long, long vows we have heard to meetin’ with no idee they would be kep’ and wuzn’t kep’.”

“Yes,” sez he, “it wuz a powerful effort. I never see the beat on’t, and I’ve been deacon goin’ on twenty years.”

“And then,” sez I, “to think of her honesty and the depth of the idee of wantin’ Him to help her not to forgit that she wanted to be good when she got to playin’ with Jack and he plagued her. She felt how different it wuz to want to be good in the quiet and rest of prayer time to what it wuz when took up with the cares of the day and the happiness and selfishness of playin’ with Jack. She wuz afraid, that little creeter wuz, that she would forgit that she wanted to be good when took up with her playthings or when he wuz plaguin’ her, jest as we be time and agin, Josiah Allen, when we git so burdened with the cares of this world or took up with its playthings that we most forgit that we want to be good.”

“Yes,” sez Josiah, “I hain’t heard anything more edifyin’ since I jined the meetin’ house.”

Josiah Allen is very sound, and what I admire in that man, what makes him so different from most grandparents, is that he hain’t blinded at all by his love for Delight; he sees clear just how fur above other children she is, and deep, and I am jest so.