CHAPTER III

If there ever wuz a girl in the world that I loved, no kin to me, it wuz Marion Martin. She lived nigh enough so I knew her hull history from A to Z, specially Z. It wuzn’t the beauty of her face nor her sweet disposition, though they wuz attractive, but it wuz her real self, the beauty and patience and duty of her hull life that made up her charm to me.

Her Ma died when she wuz fourteen, leavin’ two twins jest of a age, three singles, and a Pa with a weak tottlin’ backbone that had to be propped up by somebody, and when Miss Martin laid down the job Marion took it up. She wuz real sweet lookin’, her eyes wuz soft as soft brown velvet, and her hair about the same color, only with a sort of golden light when the sun shone on it, a clear white and pink complexion, a good plump little figger, always dressed in a neat quiet way, and pretty manners, so gentle and lovely that I always felt when I see her like startin’ up that old him:

“Sister thou art mild and lovely,

Gentle as a summer breeze.”

But didn’t always, knowin’ it would make talk. But I had noticed that she begun to look wan and peaked. I knowed that she had a lover, a good actin’ and lookin’ chap, that I liked first rate myself. He had been payin’ attention to her for over two years, and I wondered if the skein of true love that had seemed to run so smooth from the reel of life had got a snarl in it. I mistrusted it had, but wouldn’t say anything to force her confidence, thinkin’ that if she wanted me to know about it she had the use of her tongue, and had always confided in me from the time she used to show me her doll’s broken legs and arms with tears.

Marion wuz well educated and always the most helpful little thing about the house. She wuz one of the wimmen who would make a barn look homelike, a good cook, a real little household fairy, and Laurence Marsh had always seemed to appreciate these qualities in her. Her Pa wuz well to do, so Marion had enough to do with, but the care of the family all come on her, her Pa, the two twins, and three singles makin’ quite a burden for her soft little shoulders to bear. But she seemed to be strengthened for it some way, I guess the Lord helped her. She had jined the church when she wuz fourteen and wuz a Christian, everybody knew. She kep’ the house in perfect order, with the help of one stout German girl, makin’ mistakes at first but gittin’ the better of ’em as time went on, takin’ the best of care of the baby girls, kept an eye on the three unruly boys, kep’ ’em to home nights jest by lovin’ ’em and makin’ home a pleasanter place than they could find anywhere else, injected courage and hope into her Pa’s feeble will in jest the same way by her love and cheerful, patient ways.

She studied music chiefly so the boys could have some one to play for ’em—they had good voices and loved to sing—studied all the health books and books of household science so she could take the right care of her babies, and her home improved every year, so that now, when she wuz nineteen, I told Josiah that Marion Martin wuz jest as perfect as human bein’s can be. You know folks can’t be quite perfect, or else they would flop their wings and fly upwards. And oh, how Marion loved her baby girls, two plump, curly haired little cherubs, and how they loved her, and how her Pa and the boys leaned on her! And I could see, if nobody else could, how her heart wuz sot on Dr. Laurence Marsh, and I didn’t blame her, for he wuz as fine a young chap as there wuz in the country. He wuzn’t dependent on his profession, he had plenty of money of his own, that fell onto him from his Ma. And he’d paid her so much attention that I spozed he would offer her his heart and hand, though I thought mebby he wuz held back by the thought of how necessary she wuz in her own home. But it had come to me, and come straight—Elam Parson’s widder told it to Deacon Bissel’s aunt, and she told it to Betsy Bobbett’s stepdaughter, and she told Tirzah Ann, and she told me; it come straight—that Marion’s Pa had been seen over to Loontown three different times to the Widder Lummises, and I said to myself the Lord had planned to lead Marion out of the kinder stuny path of Duty into the rosy, love-lit path of Happiness, and I felt well over it.

But who can know anything for certain in this oncertain world? One day, when I had just been congratulatin’ myself while I washed my breakfast dishes about the apparently happy future waitin’ my favorite (Miss Bobbett had been in to borry some tea and told me she see the Widder Lummis in the store the day before buyin’ a hull piece of Lonsdale cambric. And I can put two and two together as well as the best. So I wuz washin’ away with a real warm glow of happiness—my dish water wuz pretty hot, but that wuzn’t it entirely), Josiah come in and said he wuz goin’ right by Marion’s on bizness, and I could ride over and stay there whilst he wuz gone. He wanted to go right away, but he wuz belated by the harness breakin’ after we got started, so it wuz after the middle of the forenoon before we got there.

Marion wuz dretful glad to see me and visey versey, yes, indeed! it wuz versey on my part, but I thought she looked wan, wanner than I had ever seen her look. The hired girl had gone home on a visit, and her Pa had took the two little girls and the boys out ridin’, so Marion wuz alone. And as I looked round and see the perfect order and beauty of her home, and my nose took in the odor of the good dinner, started early, so’s to be done good (it wuz a stuffed fowl she wuz roastin’ and cookin’ some vegetables that needed slow cookin’), and as I looked at her, a perfect picture with her satin brown hair, her pretty blue print dress, with white collar and cuffs and white apron with a rose stuck in her belt, I thought to myself the man that gits you will git a prize. But I wuz rousted from my admirin’ thought after I had been there a little while by Marion sayin’ in a pensive way:

“Do you think I could write poetry, Aunt Samantha?”

“Poetry?” sez I. “I d’no whether you could or not.” But as I looked round agin I sez mildly, “Mebby you couldn’t write it, Marion, but you could live it, and you do now in my opinion.”

“Live poetry!” sez she wonderin’ly.

“Yes,” sez I, “livin’ poetry is full as beautiful and necessary as to write it, and a good deal more of a rarity.”

I knew her hull life had run along better and smoother than any blank verse I had ever seen, better than any Eppicac or Owed; it had been a full, sweet, harmonious poem of love and order and duty. But she sez agin sadly:

“I can’t live poetry; I can only do common things. I can’t read Greek or write poems, or carve statutes, or paint beautiful pictures.”

Her sweet eyes looked mournful. I wanted to chirk her up. So I sez, as my nose agin took in a whiff of the delicious food, “Folks can worry along for quite a spell without knowin’ Greek, when they can understand and do justice to a well cooked meal of vittles.” And sez I, as my eye roamed round the clean, sweet interior, “There is such a thing as livin’ a beautiful picture, and moulding immortal statutes” (I meant the dear, good actin’ little twins), “and in my idee you’ve done it, and I know somebody else that thinks so, too.”

“Oh, no, he don’t! he don’t!” And suddenly she knelt down by my side and almost buried her pretty head in my shoulder and busted into tears. And so it all come out, for all the world tellin’ me about it jest as she did when the sawdust flowed from her doll’s legs.

It seemed that Laurence Marsh had been away to a relative’s visitin’, and went to some charity doin’s and had there met a young widder visitin’ in the place, a poetess and artist and sculptor; she read a Greek poem dressed in Greek costoom, and some of her pictures and statuettes wuz on sale. He got introduced to her. She made the world and all of him, and I see how it wuz—men are weak and easy flattered and don’t know when they’re well off—the bright, pure star that had lit his life so long didn’t seem so valuable and shinin’ as the dashin’ glitter of this newly discovered meteor (metafor). The widder had writ to him and he had writ to her, and his talk since then had been full of her, and I see how it wuz, he wuz kinder waverin’ back and forth, though I mistrusted, and as good as told Marion so, that his love for her wuz as firm as ever, it wuz only his fancy that had been touched.

Well, if you’ll believe it, that very afternoon after I’d got home, who should come in but Laurence Marsh, he brought some legal papers he had been fixin’ for Josiah—and I treated him quite cool, about as cool as spring water, I should judge, for I didn’t like the idee of his usin’ Marion as he had, though of course he wuzn’t engaged to her, and had a right to pick and choose. And, for all the world, if he didn’t go to work and confide in me. It duz beat all how folks do open their hearts to me; I spoze it is my oncommon good looks that makes ’em, and my noble mean, mebby, and if you’ll believe it, and though I hadn’t no idee I should, I did feel kinder sorry for him before he got through. He appreciated Marion, I see, to the very extent of appreciation, but his fancy had been touched, the romance in his nater had responded to Miss Piddockses romance.

“Miss Piddock?” sez I, “she that wuz Evangeline Allen?”

“Her name is Evangeline; so suited to her,” sez he.

“A widder with three children?” sez I.

“Yes, three beautiful little cherubs; I love them already from their mother’s description.”

“Why,” sez I, “Miss Piddock is related to Josiah on his own side, and we’ve been layin’ out to go and see her, but sunthin’ has hendered. She lived out West, and has only moved back a year or so ago. We’ve writ back and forth; and Josiah and I got it all planned to stop and see her,” sez I; “I, too, have been greatly took with her writings.” His handsome face grew earnest, he has perfect confidence in me, and sez he:

“I can trust you, after you have been there will you tell me what you think of her? Will you?” And sez he, “I feel that you will love her, adore her; for if she is so lovely away among strangers what a jewel she will be in the precious setting of her own beautiful home! She has described it to me, and I have loved Nestle Down jest from her description.”

I sez coolly, “Josiah and I hain’t goin’ to be sent out like spies to discover the land; why don’t you go yourself?”

“She don’t want me to visit her,” sez he; “she is so sensitive, so delicate, she has some reason I do not understand, and my duties to the hospital tie me here until my vacation, which seems an age. But my life’s happiness depends upon my decision,” sez he.

Well, I didn’t give no promises nor refuse ’em. What made me more lienitent to Laurence Marsh wuz that I, too, had such feelin’s of deep respect for Evangeline Piddock. I, too, had read with a beatin’ heart some of her poems on the beauty and sacredness of home and domestic happiness, her glorification of Mother Love and Duty, and at a relative’s I had seen some of her pictures and statuettes in stun, beautiful as a dream—she wuz truly a disciple of Art and Beauty and a Creator. And then—I heard his ardent words, I see the light in his eyes. And oh, the joys and pains and the dreams of youth, the raptures and the agonies! I could look back and feel ’em agin in memory. The impatience with Destiny, the hopes, the uncertainty, the roads that branch off in so many different ways before the hasty impatient feet. Setting at rest at eventide in the long cool shadows, don’t let us forget the blazing skies, the heart beats, the ardent hopes, the ambitions, the perplexing cares of the forenoon.

Well, if you’ll believe it, the very next Sunday after that Marion’s Pa married the Widder Lummis, stood up after meetin’ and married her in a good, sensible, middle-aged way, and brung her home, and Josiah and I wuz invited there the next week a-visitin’. We’re highly thought on in Jonesville.

I found Marion’s stepma quite a good lookin’ woman, full of animal sperits and dressed handsome; she seemed good enough to Marion on the outside, but I could see that home wuzn’t what it had been to Marion in any way; her new Ma wanted to go ahead and be mistress, and thought she had a right to, and she didn’t keep the house as Marion did; things wuzn’t dirty, but if the house resembled any poem at all it wuz a poem of Disorder and Tumult. She wanted the two boys and the twins to like her, and she humored ’em, gin ’em candy and indigestible stuff that Marion never approved of, but they did highly, and they seemed kinder weaned from Marion and took up with their good natered, indulgent new Ma. And of course Marion’s Pa, as wuz nateral, wuz all engrossed in his new wife; she wuz healthy, handsome, and a good cook. Poor Marion! in the new anthem they wuz all jinin’ in there didn’t seem to be any part for her voice. She looked like a mournin’ dove; my heart ached for her.

Towards night I see her leanin’ up against the west winder of the parlor lookin’ out sadly, and, though the settin’ sun wuz on her face, it couldn’t lighten the shadder on it. I went up to her and laid my hand on her shoulder, and I see then that her eyes had been fixed on the pretty cottage Dr. Marsh had jest bought, the prettiest place in Jonesville, a sort of a stun gray house settin’ back in its green trees with a big lawn like velvet in front, all dotted with flowering shrubs and handsome trees. But I never let on that I knew what she wuz lookin’ at. But I sez, as I laid my hand tenderly on her shoulder:

“Dear, I shan’t see you agin for some time, as we’re goin’ to make a few visits, if I can get Josiah started.”

She lifted her big sad eyes to mine, they wuz full of tears, and she didn’t need to say a word. Her tragedy wuz writ there, the loss of everything she had loved and held dearest in her life; she didn’t need to speak, I read it all, it wuz coarse print to me, I didn’t need specs. And she read what she see in my eyes, the deep love and sympathy I wouldn’t profane by puttin’ into words. No, I jest bent down and kissed her and she me, and, havin’ passed the compliments with the new Miss Martin, we went home, and the next day we started on our tower.

Well, as we approached Pennell Hill, the abode of Evangeline Allen Piddock, I looked anxiously at myself and pardner and picked off some specks of lint from his coat collar and my mantilly and anxiously smoothed the creases of my umbrell and tried to fold it up closter and more genteel, but I could not, it would bag, but I felt a or in approachin’ her home, for I had studied her poems a sight and almost worshipped ’em, and through them the writer, you know sunthin’ as it reads, “Up through Nater to Nater’s God.” So I had looked up through her glorious poems of Love and Home and Childhood and Beauty, her divine poems and statutes, up to the author, and my soul had knelt to her, and thinkses I, I am now on the eve of enterin’ a home more perfect and beautiful than my eyes have ever beheld, presided over by a perfect angel. Of course I didn’t spoze she had wings or a halo, knowin’ a woman couldn’t git around sweepin’ and dustin’ worth a cent with white feather wings, and knowin’ the halo would more’n as likely as not drop off when she wuz smoothin’ rugs or pickin’ posies to ornament her mantelry piece. But I expected to see a woman perfected as I had never seen her before in every way. And I not only paid attention to the outside of our two frames, but I tried to pick out the very finest soul garment I had by me, to clothe my sperit in, knowin’ then that it wuz hardly worthy of her.

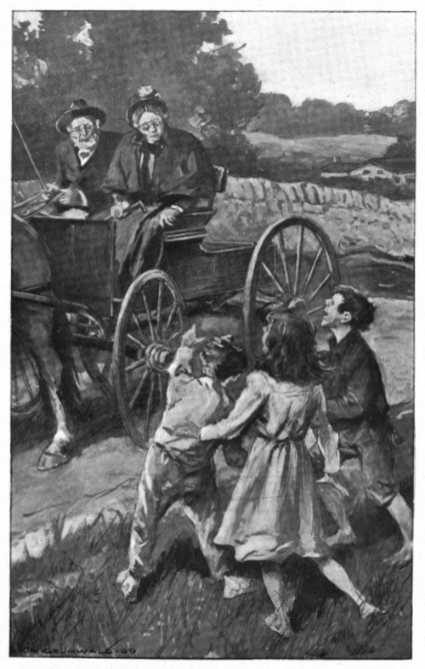

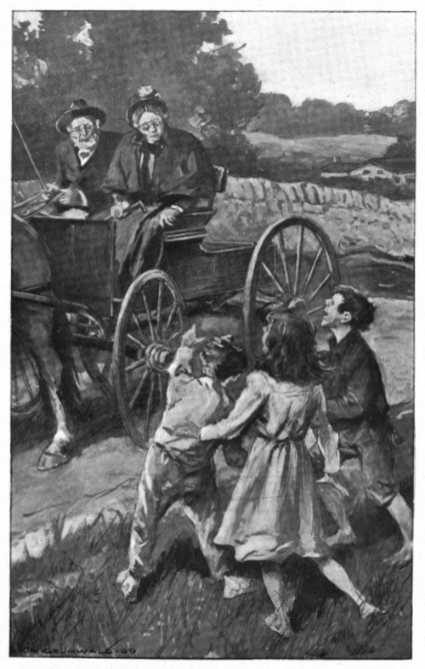

AND THEN ALL THREE ON ’EM YELLED OUT: “RUBBER NECK! RUBBER NECK!”

But my meditations wuz broke in on about a mild from Pennell Hill by seein’ a strange lookin’ group of children ahead on us; they wuz bareheaded and clad in ragged dirty garments, and their faces and hands and feet wuz as near to Nater’s heart as dirt could make ’em.

Their manners, too, wuz sassy, and grotesque in the extreme, for when we stopped and I asked ’em politely if they could tell us where Miss Evangeline Piddock lived, the oldest one sung out:

“What do you want with her? You can’t see her anyway, she’s abed!”

“No,” sez another of ’em, “she won’t look at you, you’re too homely.” And still another stuck a grimy forefinger on the side of a smudgy nose and sez, “What are you givin’ us?” And then all three on ’em yelled out, “Rubber neck! Rubber neck!” Some sort of a slang word, I spoze—and then they kicked up their dirty heels and run and jumped over a fence, and one boy turned two or three summersets, while the other ones kicked at us. Worse lookin’ children I never see, nor worse actin’ ones, not in my hull durin’ life; I felt stirred up and mad clear to my bones as they disappeared over a hill. And I sez to Josiah:

“I should think that the ennoblin’ influence of Evangeline Allen Piddock would have elevated even neighborin’ children and kep’ ’em from bein’ perfect savages like these.”

And Josiah sez, “I’d love to try the ennoblin’ influence of a good birch gad on ’em,” and I didn’t blame him, not a mite. Anon we approached a shamblin’, run-down lookin’ place, the house with the paint all off in spots and the picket fence dilapidated, the pickets and rails hangin’ loose, and weeds runnin’ loose over the yard, and Josiah sez, “We might inquire here where Evangeline lives.”

I sez, “She wouldn’t have anything to do with folks that live in such a lookin’ place, but it wouldn’t do any hurt to inquire.”

So Josiah approached the rickety piazza, and carefully stepped up on the broken doorstep and rapped, the door-bell hangin’ down broke. He rapped agin and yet agin, and the third time the door wuz opened and a female appeared clad in a long flowing robe of sage green, and her kinder yellow hair hangin’ loose, only banded in a Greek sort of a way with a dirty ribbin and the robe wuz dirty and two or three holes in it.

Sez Josiah, “Mom, can you tell me where she that wuz Evangeline Allen lives, Miss Piddock that now is?”

And then the female struck a sort of a graceful attitude and sez, “I am Evangeline Allen Piddock.”

You could have knocked me down with a hair-pin, and my poor Josiah wuz also struck almost sensible, and sez he, “Well, we’ve come!” And the female looked down on him, still holdin’ that graceful attitude. But I broke the deadlock that ensued by callin’ out from the democrat, I wuz only a little ways off:

“Miss Piddock, let me introduce Josiah to you.”

She come forward eagerly and sez with effusion, “Is this Cousin Josiah Allen?” And she shook his hands warmly. “And is this my dear Cousin Samantha?” sez she, approachin’ the vehicle and holdin’ my hand in both of hers. “Descend from your equipage!” sez she. “Welcome, dear cousins, to Nestle Down!”

“Thank you, Evangeline,” sez I, as I slowly backed out of the democrat and alighted down. But my soul wildly questioned me, “Where, where shall we nestle down?” For I couldn’t see any place. And after we got our things off and wuz visitin’ my soul still kep’ up this questionin’, “When, when shall I nestle down? And where?” For the outside of the house wuzn’t a circumstance to the inside; everything that could be out of place wuz, and everything that could be dirty lived up to its full privileges in that respect. The hired girl, a shiftless critter, I could see, wuz sick with nooraligy, but appeared with a mussy, faded out, calico wrapper and a yeller flannel tied round her face, and inquired what she should git for supper. Evangeline wuz at that minute describing to me a statute she had in her mind to sculp, but she left off and gin the girl some orders, and then kep’ on with her talk.

She sez, “My mind revels in the heroic, the romantic, it spreads its wings and flies away from the Present and the Real into the Beautiful, the Ideal.”

And I thought to myself I didn’t blame the soul for wantin’ to git away somewhere, but knew that it ort to be right there up and a-doin’ sunthin’ to make matters different.

Well, after a long interval we wuz called out to the supper table. There wuz a crumpled, soiled tablecloth hangin’ onevenly on a broken legged table, propped up by a book on one side. I looked at the book, and I see that it wuz “The Search for the Beautiful,” and I knowed that it could never find it there. Some showy decorated dishes, nicked and cracked, held our repast—thick slices of heavy indigestible bread; some cake fallen as flat as Babylon (you know the him states “Babylon is fallen to rise no more”), some dyspeptic lookin’, watery potatoes and cold livid slices of tough beef; some canned berries that had worked, the only stiddy workers I judged that had been round; some tea made with luke-warm water. Such wuz our fare enlivened by the presence of three of the worst actin’, worst lookin’ children I ever see in my life, clamberin’, disputin’, sassy little demons, reachin’ acrost the table for everything they wanted, sassin’ their Ma and makin’ up faces at us sarahuptishously, but I ketched ’em at it. The girl with the nooraligy waited on the table; her dress hadn’t been changed, but a mussy lookin’ muslin cap wuz perched on top of the yeller flannel and a equally crumpled, soiled, white muslin apron surmounted her dress, but, style bein’ maintained by these two objects, Evangeline seemed to be content.

She wuz the only serene, happy one at the table, and she led the conversation upward into fields of Poesy with a fine disregard to her surroundin’s that wuz wonderful in the extreme. Her talk wuz beautiful and inspirin’, and in spite of myself I found myself anon or oftener led up some distance into happier spears of fancy and imagination. But a howl from some of the little demons would bring me down agin, and a look at my dear pardner’s face of agony would plunge me, too, into gloom. Eat he could not; I myself, such is woman’s heroism and self-sacrifice, and feelin’ that I must make up for his arrearages, eat more than wuz for my good, which I paid for dearly afterwards, and knowed I must; dyspepsia claimed me for its victim, and I suffered turribly, but of this more anon and bimeby.

After supper we returned into the parlor, the children with variegated faces and hands, caused by berry juice and butter, swarmin’ over us and everything in the room, so I see plain the reason that every single thing wuz nasty and broken in the house and outside. They wuz oncomfortable as could be, every one on ’em had the stomach ache; and why shouldn’t they! The acid in their veins made ’em demoniac in their ways. Not one mouthful had they eat that wuz proper for children to eat, nor for any one else unless their stomach wuz made of iron or gutty-perchy. And I didn’t believe they ever took a bath unless they fell into the water, which they often did. The girl had gin their face and hands a hasty wipe with a wet towel, and their hair, which wuz shingled, wuz as frowsy and onclean as shingles would admit of.

Evangeline wuz good natered, and she had the faculty, Heaven knows how she could exercise it, of bein’ perfectly oblivious to her surroundin’s, and soarin’ up to the pure Heavens, whilst her body wuz down in a state worse than savages. Yes, so I calmly admitted to myself, for savages roamed the free wild forest, and clean spots could be found amongst the wild green woods, but here in vain would you seek for one. Her poems and statutes wuz beautiful, and she had piles on ’em, some done, some only jest begun; she wuz workin’ now on a statute of Sikey, beautiful as a poem in marble could be, and as we wuz lookin’ at it she sez, liftin’ her large, fine eyes heavenward:

“Oh, to create, to be a creator of beauty in poem or picture or statute, it seems to make one a partner with the Deity.”

“Yes,” sez I, “there is a good deal of sense in that, and I fully appreciate beauty wherever I see it.”

But, bein’ gored by Duty, sez I, “How would it work to make your own children, of which you are the author, works of art and beauty, care for them, work at them some as you do at your own stun figgers, cuttin’ off the rough edges, prunin’ and cuttin’ so the soul will show through the human, and they havin’ the advantage over your statutes that the good work you expend on them is liable to go on to the end of time, carryin’ out your lofty ideals in other lives—how would it work, Evangeline, and makin’ your own home as nigh as you can like the ideal one you dote on—wouldn’t it be better for you?”

She said it wouldn’t work at all; the care of home and children hampered her and held her down; she preferred pure, unadulterated art, onmingled with duties.

But I sez, “Wouldn’t the time to decide that question been before you volunteered to assume these cares; but after you have done so how would it work to do the very best you could with them, finish the work you have begun in as artistic and perfect a way as you can?”

I was cautious, I didn’t come out as I wanted to, so I sez, “How would it work?”

But she sez agin, “It wouldn’t work at all.” Sez she, “To describe the beauty of home and love, and child life in marble and poem and picture, she had to be severed entirely from all low and ignoble cares.”

“Low and ignoble!” sez I, for that kinder madded me. “No work a woman can do is more noble and elevatin’ than to make a beautiful home where lovely children rise up to call her blessed. Such a work is copyin’ below as nigh as mortals can the work divine; for isn’t Heaven depictered as our everlastin’ home, and God the Father as lovin’ and carin’ for His children with everlastin’ love, countin’ the hairs of their heads even, He takes such clost care of ’em?”

“He don’t order us to be shingled, either,” spoke up Josiah. “He don’t begretch the work of countin’ our hair.”

I wunk at him to be calm, for oh! how cross his axent wuz, but knowin’ that famine wuz the cause of it I didn’t contend, but resoomed:

“See how our Father beautifies and ornaments our home, Evangeline, with the glories of spring and summer, fills it with the perfume of flowers, the song of birds, hangs above us His dark blue mantilly studded with stars, and from the least little mosses in hid-away nooks up to the everlastin’ march of the planets, every single thing is perfect and in order. His tireless love and care never ceases, but surrounds us every moment in the home He makes and keeps up for us below,” sez I. “If a woman prefers to keep aloof from the cares and responsibilities of wifehood and parenthood, let her do so, but havin’ assumed ’em let her realize their duty and dignity, for,” sez I, “to create a true home, Evangeline, is worthy of all a woman’s efforts, and in such a cause even brooms and dish-cloths take on a sacred meaning.”

But she said that mops and dish-cloths and such things wuz fetters that she could not brook. And at that moment the three little imps all fell into the room demandin’ with shrieks and kicks sunthin’ or ruther that their Ma couldn’t pay any attention to, as she wuz absorbed in contemplating a slight thickness in a minute part of the butterfly’s wing on Sikey’s shoulder, and her mind wuz all took up in thinkin’ how could she prune it off without destroying the wing, it wuz so fragile and yet so highly necessary to be done. So havin’ howled round her for a spell and tugged at her Greek robe, so I see plain how the dirt and rents come on it, they hailed the passin’ figger of the hired girl in the hall and precipitated themselves onto her, havin’ previously kicked at the panels of the door so it almost parted asunder, so I could see plain how in a year’s time everything wuz in ruins outside and inside Nestle Down, and how impracticable it wuz that any ordinary person could by any possibility ever nestle down there, but Josiah here broke in agin:

“Evangeline, how long did your husband live?”

Sez she, liftin’ a torn lace handkerchief to her eyes, and leanin’ up against one of her statutes a good deal as I’ve seen Grief in a monument in a mournin’ piece, “He lingered along for years, but he wuz sick all the time, he had acute dyspepsia.”

“I thought so,” said Josiah, “I almost knowed it!”

Agin I wunk at him to keep still, but his arms wuz folded over his empty stomach with a expression of agony on him, and he answered my sithe with a deep groan, and knowin’ that I had better remove him to once, I proposed that we should retire. But Evangeline wuz describing a most magnificent sunset which she proposed to immortalize in a poem, and in spite of the gripin’ in my stomach, which had begun fearful, I couldn’t help bein’ carried away some distance by her eloquent language.

Well, at my second or third request we retired and went to bed. Our room wuz a big empty lookin’ one, the girl havin’ lately started to clean it, but prevented by nooraligy, the carpet nails hadn’t been took out only on two sides, and the children had been playin’ under it, I judged by the humps and hummocks under it. Josiah drawed out from under it a sled, an old boot-jack, and a Noah’s Ark that he had stubbed his foot aginst, and I tripped and most fell over a basket-ball and a crokay mallet. The washstand had been used by them, I thought, for headquarters for the enemy, for some stuns wuz piled up on it, a broken old hammer, a leather covered ball, and some marbles.

The lamp hadn’t been washed for weeks, I judged, by the mournin’ chimbly and gummed-up wick, and there wuz mebby a spunful of kerseen in the dirty bottom of the lamp. The bed wuz awful; the children had used it also as a receptacle for different things. We drawed out of it a old sponge, a dead rat, crumbs of bread and butter, and a pair of old shoes.

The girl who showed us up said the children had played there all the day before, it bein’ rainy, but she guessed we would find everything all right. Not a mite of water in the broken nosed pitcher, not a particle of soap, but an old apple core reposed in the dirty soap dish.

Well, I fixed things as well as I could, and we pulled the soiled, torn lace coverlet over us and sought the repose of sleep, but in vain, awful pains in my stomach attested to the voyalation of nater’s laws. Josiah wore out, and, groanin’ to the last, fell asleep, for which I wuz thankful, the oil burnt out to once, leavin’ a souvenir of smoke to add to the vile collection of smells, so I lay there in the dark amidst the musty odors and suffered, suffered dretful in body and sperit.

Amidst the gripin’ of colic I compared this home to the home Marion had composed like a rare poem of beauty, and I bethought how much more desirable is real practical duty and beauty than the gauzy fabric wrought of imagination, or ’tennyrate how necessary it wuz not to choose two masters. If one loved Art well enough to wed it and leave father and mother for its sake, well and good, but after chosin’ love and home and children, how necessary and beautiful it wuz to tend to them first of all, and then pay devotion to Art afterwards.

Well, I couldn’t allegore much, I wuz in too much pain, dyspepsia lay holt of me turribly. But amidst its twinges I remember wishin’ that Laurence Marsh could compare as I had the two homes and lives composed by Marion and Evangeline.

And then a worse twinge of pain brung this thought, a doctor I ought to have. A woman should be allowed to choose her own doctor. I said to myself I will send for Doctor Laurence Marsh in the mornin’, which I did. Josiah bein’ skairt telephoned to him to come to once. He come on the cars, arrivin’ at about ten A. M.

I guess I had better hang up a curtain between the reader and Laurence Marsh as he stood in that home confronted by Evangeline Allen Piddock and her household. I hadn’t told her who I had sent for, not havin’ seen her that mornin’, so he see ’em all in a state of nater as it were.

Yes, I will hold up a thick, heavy curtain with Josiah’s help, for I don’t want the reader to see Laurence Marshes face as he looked about him in the parlor and up by my bedside—such a bedside! His face, as he measured out the medicine, wuz, as Mr. Byron sez, “a scroll on which unutterable thoughts wuz traced.” But, amidst all his perturbations of mind and wrecks of airy castles and dreams, nothin’ could prevent him from bein’ a good doctor, though owin’ to a urgent hurry, a case of life and death, he said, he had to return to Jonesville immegiately, which he did.

But I felt so much better after takin’ the tablets twice every half hour that we started home a little after leven.

It seemed to me that home never seemed so good, so dear, and so clean to me in my hull life before, and what added to my perfect enjoyment, jest as we set down to a delicious supper, cooked by my own hands, one of the singles brought over a note to me from Marion. It wuz a invitation to her weddin’, which wuz to take place the next week.