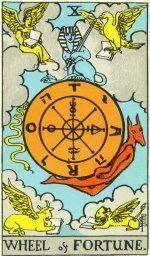

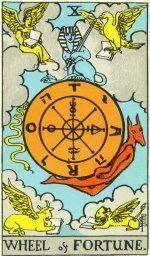

X. THE WHEEL OF FORTUNE

In this symbol I have again followed the reconstruction of Éliphas Lévi, who has furnished several variants. It is legitimate—as I have intimated—to use Egyptian symbolism when this serves our purpose, provided that no theory of origin is implied therein. I have, however, presented Typhon in his serpent form. The symbolism is, of course, not exclusively Egyptian, as the four Living Creatures of Ezekiel occupy the angles of the card, and the wheel itself follows other indications of Lévi in respect of Ezekiel's vision, as illustrative of the particular Tarot Key. With the French occultist, and in the design itself, the symbolic picture stands for the perpetual motion of a fluidic universe and for the flux of human life. The Sphinx is the equilibrium therein. The transliteration of Taro as Rota is inscribed on the wheel, counterchanged with the letters of the Divine Name—to shew that Providence is imphed through all. But this is the Divine intention within, and the similar intention without is exemplified by the four Living Creatures. Sometimes the sphinx is represented couchant on a pedestal above, which defrauds the symbolism by stultifying the essential idea of stability amidst movement.

Behind the general notion expressed in the symbol there lies the denial of chance and the fatality which is implied therein. It may be added that, from the days of Lévi onward, the occult explanations of this card are—even for occultism itself—of a singularly fatuous kind. It has been said to mean principle, fecundity, virile honour, ruling authority, etc. The findings of common fortune-telling are better than this on their own plane.

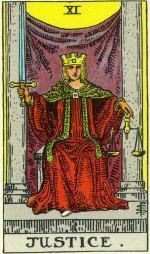

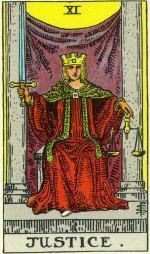

XI. XI . JUSTICE

As this card follows the traditional symbolism and carries above all its obvious meanings, there is little to say regarding it outside the few considerations collected in the first part, to which the reader is referred.

It will be seen, however, that the figure is seated between pillars, like the High Priestess, and on this account it seems desirable to indicate that the moral principle which deals unto every man according to his works—while, of course, it is in strict analogy with higher things;—differs in its essence from the spiritual justice which is involved in the idea of election. The latter belongs to a mysterious order of Providence, in virtue of which it is possible for certain men to conceive the idea of dedication to the highest things. The operation of this is like the breathing of the Spirit where it wills, and we have no canon of criticism or ground of explanation concerning it. It is analogous to the possession of the fairy gifts and the high gifts and the gracious gifts of the poet: we have them or have not, and their presence is as much a mystery as their absence. The law of Justice is not however involved by either alternative. In conclusion, the pillars of Justice open into one world and the pillars of the High Priestess into another.