5. The Ergonocracy Economic Model

5.1 Characterisation

Framework

The times in which we live are characterised by a lack of confidence on the part of most economic agents. The capitalist system has gradually weakened, which has led to successive economic and financial crises brought on by many factors: overproduction and strong competition, basic errors in banking regulation49, excessive public debt, and, most notably, cyclic speculative crises.

The capitalist system has not been able to overcome these crises. We have therefore become global witnesses to an increasing rate of impoverishment of the middle class, a fact that is aggravated by unemployment.

Some adjustments have been attempted, especially in financial activity, but these measures are as effective as palliative care for a dying man. The crisis is global and affects both rich and poor countries. The problem is further aggravated by the special demands and efforts that are required to protect the environment and combat climate change. The response to these crises has been to raise taxes and cut public spending, which has led to widespread demonstrations of protest in several countries. These have been joined by anti-globalisation movements, environmental protection movements and protests by the unemployed and disgruntled employees. People take a reduction in their accustomed living conditions very seriously. Furthermore, the trend is these problems get worse, which has generated a global context of hopelessness.

If this situation persists, there is a serious risk of violent revolutions erupting around the world, which can force the launching of a new wave of autocracies, as has happened throughout so much of our history. As in the past, dictatorships bring no solutions and will only contribute towards perpetuating a new ruling class that employs more hideous and repressive methods.

It is therefore of the utmost urgency to create a new economic system that is better adapted to mankind’s characteristics. This new system needs to be rational enough to avoid unnecessary turmoil by preserving the positive aspects of the existing capitalist system and be courageous enough to attempt to change its destructive aspects.

The Ergonocracy Economic Model considers that the existing capitalist system has the following positive features: natural market mechanisms, efficient entrepreneurial best business practices and the powerful instigating force of motivation instigated by profit. These are the features that should prevail. On the other hand, since the existing capitalist system has many negative characteristics, both ethical and practical, the Ergonocracy Economic Model defends the notion that the rules governing company share structure, should be changed and the employer vs. employee dichotomy should be done away with. This will prevent the exploitation of man by man and inject a strong shot of adrenaline into our dying system.

Implications of the Ergonocracy Economic Model

The economic model of Ergonocracy has implications for microeconomics and macroeconomics.

In terms of microeconomics, this model has the main purpose of proposing a naturally balanced system that will do away with the exploitation of man by man. The paradigm is configured so that employers and employees no longer coexist, only members with equal status. At the same time, however, in an attempt to reconcile the best of both worlds, the freedom of private initiative and the advantages of market economies are preserved.

The secret of the success of this model lies in the way the process will be conducted as well as in its empirical nature. Several alternatives for the conversion of existing companies will be suggested along with a set of rules to be implemented.

As a result of these regulations, no one will be allowed to work directly for another entity. Thus, any person performing labour or business functions will have to be a partial owner of a company. Only companies will be allowed to perform services, produce goods and issue invoices.

In addition, nobody will be able to hold less than a five per cent company share, as there will be a pre-set theoretical maximum of twenty members per company. Although this idea may seem strange and impossible to implement, it will be proved otherwise. This chapter explains in detail how this model can be implemented, including several methods destined to ensure a smooth and appropriate transition.

In terms of macroeconomics, we will advance several concepts, such as the existence of money only in digital form and the gradual replacement of existing stock exchange markets, which will be replaced by a company managed nominal Titles Model (a new form of participation in company capital), a new concept of interest rates and new tax models.

With amendments suggested at both levels - micro-and macroeconomic - we believe that it will be possible to minimise the adverse effects caused by the capitalist system, such as glaring economic inequality, one-sided human exploitation, speculative cycles, structural imbalance and the concentration of capital in massive corporations, etc.

Of course, the Ergonocracy Economic Model assumes that all companies will be profit-oriented, including previously referred to Concessionary and Sub-Concessionary Companies. Remuneration from profits and premiums (bonuses) will be the only income allowed for citizens, as salaries, passive interest rate income, speculative earnings and rent50 will all cease to exist.

5.2 Underlying principles

The principle of non-exploitation of man by man

Economic exploitation of man by man is considered one of the most important factors in the destabilisation of society. It also causes jealousy and anger and helps create social class differences, which can lead to the outbreak of antagonism and to a sudden breakdown of the economic and social structure.

The problem is that people have to work to survive. It is easy to observe that most workers have little involvement in the objectives of their organisations. Workers typically live bitter, conformed and postponed lives, spending their work time watching the clock and looking forward to free time, weekends and holidays. This happens because, generally speaking, workers do not feel that the organisations for which they work, belong to them in any way. Consequently they put forth the least possible effort, giving a minimal level of performance to avoid problems and to hold onto their jobs and benefits.

In microeconomic terms, this reasoning makes the most sense, given the fact that most salaries are fixed, i.e. they are not proportional to the actual effort expended nor to the results achieved. Even when there are variable premiums (bonuses), in most cases there is little fairness or efficiency in the selection process. This leads us to the conclusion that labour systems should be organised in such a way that all players can feel that the organisation belongs to them. Firstly, we should define the concept of exploitation, which can be interpreted in several ways:

One possible definition is that exploitation occurs when the amount that someone receives for his or her work is significantly less than the value that the results of his work51 has created. This would be one hundred per cent correct if labour (the ability to work) were the only factor52 behind production. There are usually other factors, however, such as land (natural resources, gifts from nature), capital goods (man-made tools and equipment) entrepreneurship and technology. This being the case, a wider notion of capital must be utilised, including the high risk of entrepreneurship that is associated with investment. Therefore, this begs the question of the definition of fair proportion, i.e., what proportion is due to the labour factor. However, although this factor is essential, labour tends to be overvalued, especially because most human beings are part of this production factor and because this issue is a very important element in most people’s lives. Thus, issues involving labour are always associated with certain notions of injustice and abuse, especially when someone gains directly from the effort of others, which leads to the creation of conditions where people start to begin to question the legitimacy of the authority of some people over others.

Another way to understand the concept of exploitation is to see the issue from another angle, i.e., in terms of social objectivity. Imagine the example of a company where workers do not receive enough income to afford a decent, healthy life. Nevertheless, this definition is short-sighted because the business activity itself may not be very rewarding and not allow the necessary income to be generated.

It is also possible that people may feel exploited in a broader sense, not by another individual, but by the whole of society; this could happen in cases where people are unable to find work and are forced to beg in the streets.

Probably the most consensual definition of exploitation maintains that this phenomenon occurs when an employee does not share in a significant portion of the results of his or her work. Proponents of Ergonocracy believe that the key issue is precisely the process of sharing. They argue that all players in the production process must receive an income according to the share that they hold in the production unit. Besides, everyone who is able to participate should enter the production system management process.

It can therefore be said that exploitation will end, as everyone should have an income proportional to his or her share, although some members will hold larger shares than others. Consequently the division of power and income will not necessarily be equal. However, everyone will have an incentive and an opportunity to play a crucial role within his or her organisation in order to gain increased shares and income.

With the application of this model, we also seek to abolish most hierarchical levels, in particular the status of employer and employee. According to this model, all members should have equal rights within the company, although obviously some of them will hold larger share percentages than others according to established minimum and maximum limits set to maintain a certain harmony and balance of power.

Principle of motivation

One of the consequences of the aforementioned principle of non-exploitation of man by man and the application of a system in which all operational members are shareholders, is that an individual could naturally struggle much more if the person worked for his or her own company than if he or she worked for another entity. In fact, any entrepreneur or business man can testify to the fact that working for oneself is less tedious and more exciting.

At this point the importance of meritocracy, a widely praised but little used concept, should be recognised. In practice, the implementation of a just and efficient meritocracy system is extremely difficult, as most work functions cannot be measured quantitatively. Even in rare cases where work results are measurable, such as sales, people will not necessarily be evaluated correctly. Certain salesman may have received an unfavourable zone of activity or a client group with reduced buying power.

In addition, the criteria used to evaluate workers are often subjective, as they are subject to evaluation by other individuals whose interests are not always based on honesty and fairness.

Regarding vertical assessment evaluation criteria, and in this case we are referring to evaluations conducted by managers, it may be noted that these assessments can be distorted by the subjectivity of the evaluator. As well-intentioned as this person is, he or she may be swayed by empathy or favours owed.

The great advantage of the Ergonocracy system - where all employees are members of their companies - is that everyone has a vested interest in the organisation and genuinely strives for its success. In this way, people are pulling together, which is what is supposed to happen in a genuine meritocracy system.

This happens not only because each member’s monthly income is directly indexed to profits and indirectly to company production, but also because all members have an interest in rewarding and attracting co-workers who truly stand out.

In the traditional capitalist system there is a set of entry barriers for new competitors in most business areas. Among these barriers we can include: lack of information, large scale financial investments and psychological barriers including cultural fears.

In addition, there are certain activities which, by the very nature of their markets, require high investment projects as well as enormous scale effects. It should also be noted that it is in the interests of existing companies to prevent new competitors from entering the market. One of the ways of doing this is to reward individuals considered most critical to the organisation. Although this is a form of meritocracy, it has a pejorative effect, as it contributes to keeping the best placed employees, who could accomplish more and rise higher in the organisation, in the same place.

The Ergonocracy Economic Model argues that what is important is that all citizens change their mind set and that everyone should have access to means and opportunities to participate in the “business game”, in such a way that nobody is directly or indirectly left out.

Ambition and greed are inherent qualities in human nature, for good and bad. Unless these traits become excessive, they can play an important role by providing positive motivation, helping individuals overcome obstacles and the fear of facing new challenges in our ongoing search for a better life.

With the implementation of this model, money will still be unevenly distributed, albeit more blurry, but this is not necessarily negative as long as everyone has the opportunity to compete and earn money.

It should be stressed that money is not necessarily evil, as it merely takes on the value that society as a whole has decided to give it, that of facilitating economic exchanges. It should not be considered unethical for someone to earn a lot of money provided that the person who paid for the service benefited from the exchange. In other words, in this case an equilibrium will have been achieved between a positive (the service) and a negative (the payment). What is unquestionably reprehensible are all evil practices, carried out just for fun or for any other reason, for which there is no tangible gain achieved by the infringer. In other words, what is objectionable is the occurrence of an evil act against someone or something where no gain has been obtained other than sadistic pleasure.

Principle of the abolition of virtual slaves

In traditional capitalist systems, most people spend their time simply surviving, with only sporadic leisure periods to look forward to. Resigned to having to work for a living in order to survive, they live unhappy, unfulfilled lives. In short, most of these people feel and live like slaves. This makes them virtual slaves, as someone who feels like a slave is just as much a slave as real slaves of the past.

The principle that is to be described is somewhat controversial because it defends the notion that no human being should be a virtual slave.

The Ergonocracy Economic Model helps to solve this problem because every worker will have the opportunity to become a member of his or her company, giving the person other opportunities and perspectives which he or she will never have as a mere employee.

Even so, most people will still have to work for a living. There are no easy solutions to this problem, which Ergonocracy will not try to solve, simply because there are other, much more serious problems to deal with.

One day, if this human project reaches a highly developed stage, it may be possible to abolish all virtual slaves by giving each individual the choice to work or not. This idea will be approached in the “utopian” Ergonotopia stage in a later chapter. In this utopian society certain specific rules will have to be established in order to prevent society as a whole from falling apart and descending into a spiral of sloth.

Principle of reducing the size of enterprises

This principle aims to reduce the adverse and pernicious effects of the capitalist system, namely the behaviour of international corporations. In order to reduce the power of these mega-structures, the Ergonocracy Economic Model states that mechanisms should be inserted to limit the size of companies and corporations, in particular.

It is also in this context that the Ergonocracy Economic Model presents the rule that limits the maximum number of company members to twenty. It is clear that a company can expand and spread out by holding other companies. However, the negative effects are minimised by the specific mechanics of this system, where nobody is left out and everybody is entitled to participate in decision-making processes.

“User-payer”53 Principle

Ergonocracy defends the notion that, when possible, the user-payer principle should always be applied. It is not merely a question of fairness, but a practical measure as well. When something is paid for and it works successfully, it is considered a worthwhile investment. We can observe that when something is free, people may use it merely out of habit or just because it is free. Therefore, statistics about the use of these services can be deceiving54. This principle also serves to moderate usage and to prevent abuse.

5.3 Microeconomic rules and guidelines

The Microeconomic Ergonocracy Economic Model features the introduction of specific, new rules that are divided into three distinct pillars:

-

Rules concerning shares and statutes.

-

Rules concerning types of partners.

-

Rules concerning member compensation.

Rules concerning shares and statutes

According to Ergonocracy, a regulation governing shares and statutes should be implemented under the following set of rules:

-

Rule number one - All companies, regardless of their size, should be converted into only one type: Company Limited by Shares55

-

Rule number two - In order to perform a function in a company, every citizen, provided that he or she is mentally and physically able, must hold a stake (share) in the capital of this company i.e. he of she must become a shareholding member of the company; therefore, no company will be allowed to hire employees, since every working person must participate in the capital of the company where he or she works.

-

Rule number three - Only companies may provide services, produce goods or issue invoices, i.e. no citizen may carry out such activities directly in his or her own name.

-

Rule number four - No company member will be allowed to hold less than a five per cent share of his or her company, the minimum share allowed. The logical implication here is that companies will be limited to a maximum of twenty members.

-

Rule number five - This rule will stipulate that all existing companies that employ more than twenty individuals, should be divided into smaller companies using geographical or functional criteria; the head company should hold shares in these smaller companies and have the right to appoint a partner (member) to represent his or her interests.

Rule number four stipulates a maximum number of twenty members in each company, the cornerstone on which Ergonocracy Microeconomic Model is supported.

In practice, this limit of a twenty member maximum may appear to be a serious constraint. However, it can be transformed into an economic opportunity, as will be described later. In fact, every company should work as a well-organised team and operate within a flexible, responsive structure. Being small in size helps to achieve this goal. It is easy to see why organisations with too many members are characterised by a sense of loss of identity.

Indeed, the ideal size considered for most companies varies between four and thirteen members, depending on the sector of activity and the specific characteristics of the company. This size blueprint was not obtained by chance; on the contrary, it has been achieved from observing the structural characteristics of human social psychology, taking into account the way our species lived during the vast majority of our evolutionary history. In past epochs, tribes could send teams composed of a small core of operational members to carry out missions of hunting, patrol or defence.

This size model also takes into account the way most teams work, for instances, military teams56, sports teams, business teams, etc.

In any case, for each sector of activity and for each company in particular, there is an ideal number of employees/members that maximises the efficiency of the organisation. This is an empirical path that each start-up company will have to walk.

As stated in rule number five, all existing companies whose workers numbered more than twenty will need to put into place a business plan designed to divide the head company into the necessary number of smaller companies. This division should need to be conducted using geographical or functional criteria and a tightly-knit economic group will need to be created in which each smaller company could have special obligations to its group, but should also have the opportunity to take on new initiatives in other areas.

As referred to in rule number five, the head company should hold shares in these smaller companies and have the right to appoint a partner (member) to represent its interests. As the majority shareholder, the head company should also decide annually whether or not to keep or change its representative. It makes sense that this representative should be an active partner in the head company to which he or she should return at the end of his or her representation mandate.

Among other difficulties, it is obvious that companies with too many members are in a poor position to provide financial incentives to their members. As the income generated has to be split among many people, each member’s part is too insignificant to constitute a work incentive.

As an illustrative example, imagine a large restaurant, with over one hundred employees, where all tips are placed in a vault for later to be divided among all workers. What is to be observed, is that for each of the waiters the encouragement and incentive to do their best, is hampered by the fact that for every dollar received as tip, only a penny will end up in their respective pockets.

On the other hand, the other extreme is also detrimental to companies. Organisations with few members may not earn sufficient critical mass nor achieve the necessary degree of expertise and know-how required to thrive in the market. It is therefore desirable that each organisation should try to become large enough to improve its capacity to compete and to benefit from scale economies so that it can develop its skills, gain control over more regions, improve its response times and allow specialisation in core activities. Partnerships with other key companies is therefore a crucial aspect.

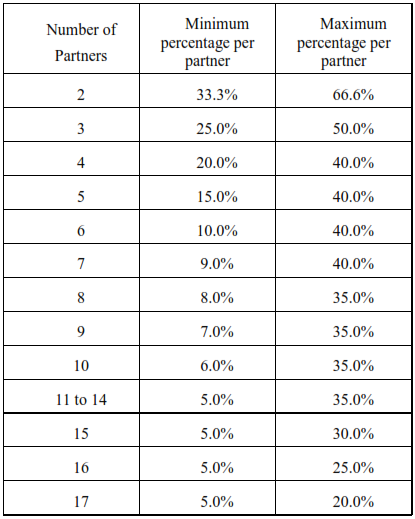

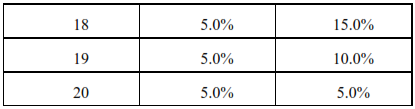

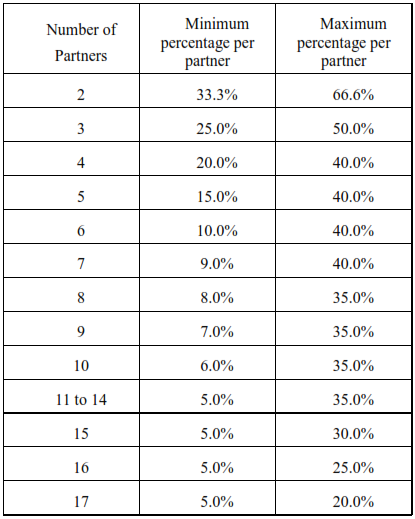

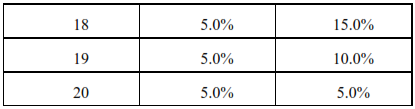

The table bellow refers to rule number six, which sets the Minimum and maximum share percentage limits to be held by each partner as explained below in the following table:

The aim of this regulation is to create a balance of power among members so that nobody stands out as too powerful. Simultaneously, the system should have to reflect the eventuality that a member could rise in the organisation, especially if he or she had proven to be more promising and dedicated.

Rules concerning the types of partners

Next, let’s discuss rule number seven, which defines three types of company members, namely: exclusive, consulting and investors:

-

Exclusive members are characterized by being active partners exclusively allocated to the company where they could perform full schedule activities.

-

Consulting members are also active partners, but could work part-time, as they will be allowed to hold executive roles in two or more companies. Accordingly, a set of strict objectives must be defined for each of these members, including the conditions under which his or her obligations should be performed, such as work schedules, objectives and rewards.

-

Investor members are not active partners; their participation in companies is motivated by the need to invest their money. Their role is sporadic and is essentially limited to intervening in strategic decisions, such as changing the activity of the company, or decisions that involved the company’s taking on significant debt. Investor members could play a passive role and should not be able to participate in daily decision-making processes.

The active shareholder managers’ core should be composed of exclusive and consulting partners. They will perform specific functions within the company.

With this model, the self-employed one-man company concept will also be abolished, as in the professions of lawyers, architects, etc. In some cases and to a greater or lesser degree, these kinds of professionals are subject to the constraints imposed by their customers. They are the weakest link in these relationships, especially when they depend on only one client.

Thus, rule number eight should reinforce rule number six, stipulating that each company will need to have at least two members and that both of them will have to play active roles (as exclusive or consulting members). The purpose of this rule is to encourage a culture of mutual assistance and to help create an environment of entrepreneurship, which is generally accepted as healthy for business.

Another advantage is that with two or more business partners, there will be a tendency to increase the number of clients and thus reduce dependency on a few clients. This will help place companies on a more equal footing in business negotiation processes.

Besides, in case one of the partners is ill or absent for any reason the other partner will be able to substitute him providing a better service to the final client.

This rule applies to all kinds of professionals, even those who have typically been regarded as solo, as in the case of singers, actors, writers, scientists, etc. These individuals should tend to choose as partners other people who they think may add value to their activity, as these partners will necessarily share the same business vision. A new partner could be a colleague in the same artistic field, an agent, editor, assistant, etc.

Of course, it is clear that the distribution of shares between these two or more partners should reflect their individual importance to the whole organisation. Thus, it is conceivable that one of the partners could have ninety per cent of the shares and the other only ten per cent. This is an exception57 to rule number six and will only apply to specific groups of professionals in the world of sports, the arts and science.

An exclusive partner in a given company is allowed to become an investor partner in another company, provided that the two companies operate in distinct activity sectors, i.e. provided that they are not direct competitors.

However, an exclusive partner should not be allowed to play active roles in both companies; only one of them.

As previously explained, each company member can act as a partner in his or her own name or operate as a delegate of the head company that holds shares in his or her company. In this case, the same privileges and obligations that hold true for any other shareholder will apply.

Rules concerning member compensation according to merit

Redistribution Profits and premiums (bonuses) should be the only remuneration allowed for citizens, as salaries, passive interest rate income, speculative earnings and rents58 should all cease to exist. Thus, member compensation should consist of two types of income:

-

Redistribution Profits - this will apply equally to all types of partners (Exclusive, Consulting and Investors); each shareholder will be assigned a redistribution profit value according to the percentage of shares held. As a general rule, it should be stipulated that each member-partner will receive a monthly value corresponding to estimated profit for that month.

-

Premiums (bonuses) - These premiums will constitute additional variable income, as an added incentive, as well as recognition of merit for top performers. These values are not indexed to each partner’s share.

Each partner’s total monthly wages will correspond to the sum of these two components: Redistribution Profits and Premiums (bonuses). These two parts could vary according to a specific formula, as follows:

-

Step A - At the end of every month, the member responsible for financial matters should analyse the accounts and make a projection of the estimated annual company profit; these calculations should be supported by available up to date accounting figures.

-

Step B - It should be up to each company to decide by a simple majority vote what percentage of the company profit will be redistributed each year. The remaining non-distributed profit will constitute the company's reserves. Therefore, at this stage, the total annual amount to be redistributed is obtained by multiplying this percentage by the total profit value.

-

Step C - In relation to the amount obtained in Step B:

o 50% of that value should be automatically allocated to Redistribution Profit; then, the financial controller should calculate that month’s profits59; each shareholder monthly profit amount should be equal to the estimate of earnings for that monthly period and proportional to his or her