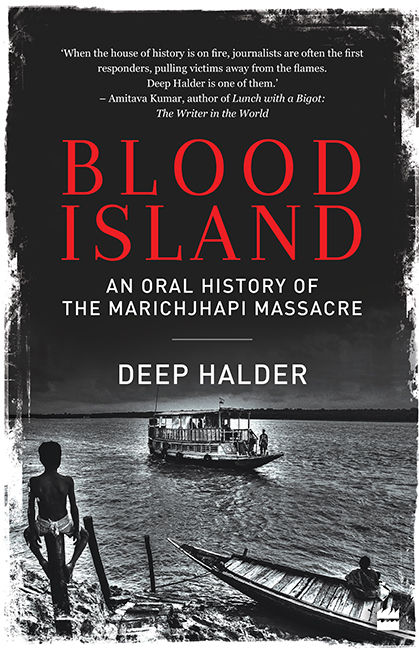

BLOOD ISLAND

An Oral History of the

Marichjhapi Massacre

Deep Halder

Baba,

without you this book would not have been written.

Rebellions were begun by people who had not read Das Capital or the Red Book. It was their reality that had urged them into rebellion.

– Manoranjan Byapari

Contents

Preface

Introduction

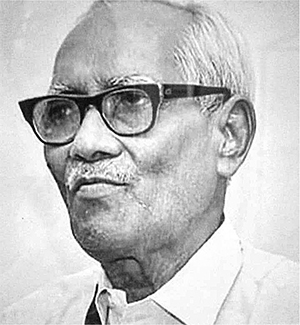

1 Jyotirmoy Mondal

2 Safal Haldar

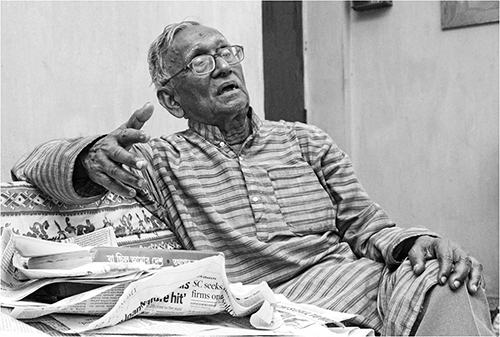

3 Sukhoranjan Sengupta

4 Niranjan Haldar

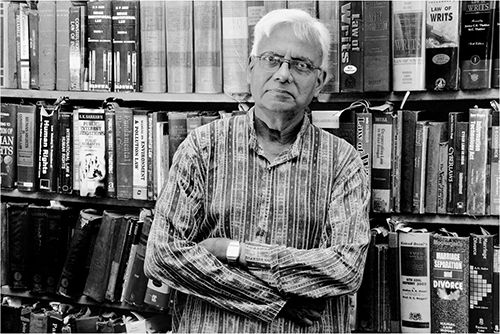

5 Sakya Sen

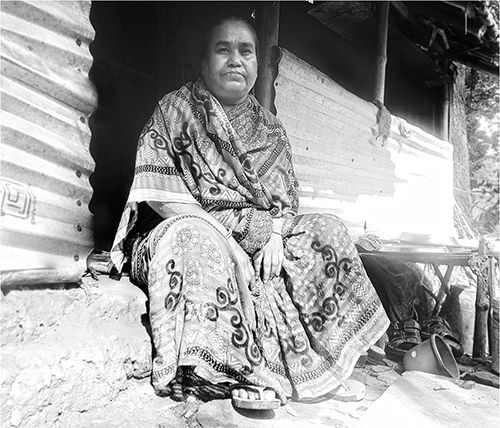

6 Mana Goldar

7 Santosh Sarkar

8 Kanti Ganguly

9 Manoranjan Byapari

Afterword

Bibliography

About the Book

About the Author

Copyright

Preface

HOW THEY KILLED THE DREAMERS IN THE

SUNDARBANS

This book is about an island time forgot. It is also about my oldest memory; a memory that is both a fairytale and a bad dream. This book is about Marichjhapi.

Marichjhapi, as cold fact and sweet lullaby, comes to me at unexpected hours – when the TV ticker screams that India will deport Rohingyas or a new story on Syria brings out that old photograph of Alan Kurdi yet again to tug at heartstrings. Even almost forty years after I first heard the story of Marichjhapi, such references take me back to an unending farm with coconut and palm trees, ponds and paddy fields, and an abiding memory of a dark secret shared in whispers as a bedtime story. It’s amazing how the most horrific sits pretty with what is serene.

I become my child self again at times like this, playing inside a two-storeyed house sitting in the middle of the seven bighas of land that used to be my weekend getaway. My grandfather, a deputy magistrate in the British-ruled undivided India, had settled in the western half of Bengal after Partition, the part that had remained with India. In his travels across the newly formed state of West Bengal, he saw in the South 24 Parganas the charms of the land he’d left behind. That land is now Bangladesh.

Taldi is one hour away by local train from the southern tip of Kolkata. It is a place so postcard perfect that my parents would not feel like forcing me

back to the city when school reopened after weekends. Our Taldi house became the way it did through months of hard work. The salty soil was made cultivable by manuring it with wagons full of new earth. Fish breeding was my grandmother’s department and the three ponds on the property offered almost every variety a Bengali palate could pine for.

Twenty-five miles from Taldi – around the time my favourite weekend sport was chasing a spotless white calf into the paddy fields with my grandfather’s walking stick – thousands of men, women and children were trying to set up their own Neverland and being chased around by officials of the new Left Front government, who were saying the ecology would be destroyed if these refugees succeeded in their endeavour. That place was Marichjhapi; and it came to me as a story through Mana.

Mana herself came unannounced as a distant cousin to look after me and tell me stories. She had a strange tongue and stranger manners. It took me some time to warm up to her, but Mana Goldar had stories for me.

Stories from Marichjhapi.

I was too young to know what rape was or fathom the full import of the word ‘refugee’. Though it was spoken many times in the house with reference to Mana in the adult conversations held around me, no one explained to me who or what a refugee is. Looking at Mana, I thought a refugee was one who had no place to go. Mana said her first home had many refugees.

She was born into, and named after, Mana Camp in faraway Dandakaranya, where her parents had been sent after East Bengal became a country for Muslims. They travelled miles to cross the border, hoping that people who looked similar and spoke the same tongue would open their homes and hearts to them, only to be pushed into the hot, humid north. It was in this squatters’ colony that Mana was born, where refugees toiled day and night for meagre wages from sarkari babus. When they protested, their mothers, daughters, sisters and aunts were taken away by sinister men. That was rape, Mana said.

Mana was in her teens when she came to stay with us. She had spent her first twelve years in Dandakaranya and one in Marichjhapi. It was a hard

word for me to say, so Marichjhapi became ‘mud island’ in her stories, an island of wet soil. Her last home, she said, was always covered in mud and they wore no slippers.

There were no sarkari babus in Marichjhapi. Men sang and women danced as the sun sank into the sea. Hope was enough to hold on to during those difficult days they spent turning a barren island into a home.

‘But it all had to end. The resident deity, Bonbibi, didn’t hear our cries,’

Mana had said as she wiped her tears.

The darkness in her eyes as she told me her tale cemented a bond that stayed. Mana left us in eight months, but Marichjhapi kept coming back to me; in stray conversations and chance meetings, the gravity of the horror gradually unfolding.

As recently as 2017, Marichjhapi slithered into my consciousness in a Bhopal newsroom, of all places during a conversation with my colleague Mokapati Poornima. She is a deep diver into lost causes; a star reporter in the newspaper I edited at the time, she travelled the length and breadth of Madhya Pradesh to scoop out stories of despair and distress.

I asked her once why she risks life and limb for her job and she said her ever curious gene must have come from her mother, who travelled from Bangladesh to Calcutta, Calcutta to Dandakaranya, Dandakaranya to the Sundarbans and back to Dandakaranya again in search of hearth and home.

‘Sundarbans? Where in the Sundarbans?’ I enquired.

‘There is a place called Marichjhapi, sir. Bengali refugees had settled there once.’

‘Your mother is Bengali?’ was all I could ask. Poornima nodded.

I then dialled Jyotirmoy Mondal, a rights activist, an old source for stories and a family friend. Mondal knows of the horrors of Marichjhapi firsthand, having witnessed the growth of the cottage industry around the tragedy and the poverty many of its survivors still lived in, even as governments bluffed and fell.

‘Tell me again what happened,’ I said. There was an urgent need in me to hear it all again, revisit stories I’d half grasped as a boy and kept putting together piece by broken piece in later years.

Mondal never tires of retelling Marichjhapi. ‘Refugee settlement was never meant to be easy. How do you handle swarms crossing over from Bangladesh to West Bengal? The problem was, when they were in Opposition, Left leaders told the Bangladeshi Hindu refugees, who were being packed in hordes to squatter camps in Dandakaranya, that if they came to power they would bring them back to West Bengal. But once in power, they backtracked.

‘Feeling betrayed by bad politics and fed up with the miserable living conditions in the camps in Dandakaranya, some refugees came and settled in the tiny island of Marichjhapi in the Sundarbans. For eighteen months they toiled to turn “mud island” into a habitat. For eighteen months, the government tried many times to evict them.

‘When your father and a few other scholars, intellectuals and journalists went there, they found Marichjhapi to be one of the best developed islands in the Sundarbans. The refugees did not ask the government for money, nor did they squat on others’ property. They only wanted a marshy wasteland.

‘But between 14 and 16 May 1979, in one of the worst human rights violations in post-independent India, the West Bengal government forcibly evicted around 10,000 or more from the island. There was rape, murder and poisoning. Bodies were buried in sea. Countless were killed even as some escaped, too afraid to tell the tale. At least 7,000 men, women and children were killed.’

‘But what about those who escaped the carnage?’ I asked him.

‘You know some of them, don’t you?’ he replied.

‘Mana,’ I whispered, to which he said, ‘Not just her.’

And no, it isn’t just Mana Goldar. I have, over the years, collected Marichjhapi’s broken fragments and tried to make it whole again.

Researchers have taken Marichjhapi to Oxbridge lecture circuits.

Sociologists, historians and Dalit activists have put out theories on what happened and why. Amitav Ghosh has fictionalized Marichjhapi in his book, The Hungry Tide.

In one of the most definitive papers on the massacre, ‘Refugee Resettlement in Forest Reserves: West Bengal Policy Reversal and the

Marichjhapi Massacre’, Ross Mallick attempts to answer why the Left Front government did what it did in 1979. ‘The Marichjhapi massacre was not that different from the Bosnian massacres, but at least in Europe the politicians responsible got indicted and had to go into hiding … However, no criminal charges were laid against any of those involved [in the Marichjhapi massacre] nor was any investigation undertaken,’ Mallick writes.

In ‘Dwelling on Morichjhanpi: When Tigers Became “Citizens”, Refugees “Tiger-Food”’, published in the Economic and Political Weekly on 23 April 2005, Annu Jalais observes the incident from a Dalit perspective. ‘The government’s primacy on ecology and its use of force in Marichjhapi was seen by the islanders as a betrayal not only of refugees and of the poor and the marginalized in general, but also of Bengali backward caste identity,’ she writes.

Most of the Marichjhapi islanders belonged to lower castes and were given the short shrift by the Left Front government, which was predominantly upper caste even though it espoused a classless, casteless society, Jalais argues.

Unlike Mallick and Jalais, I have never put pen to paper to bring Marichjhapi back for newspaper readers. I have never sat down for a drink with my academic or media friends to deconstruct the events of 1978-79.

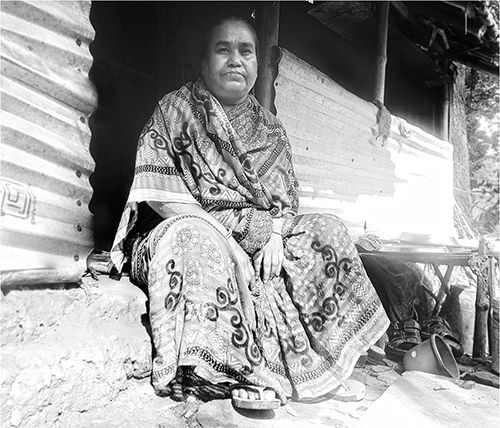

What I have set out to do, instead, is document its oral history, the tales of a few of those who lived through those dark days. Here, I have recorded Mana Goldar’s story, journalist Sukhoranjan Sengupta’s reports, refugee mother Phonibala’s nightmare, the memory of the man who swam a river to save fellow journeymen and several others who have not been able to bury their past in the bloodied ‘mud island’.

Their nightmare is mine too. This is how it all began. And ended.

Introduction

Nobody knows, nobody can ever know, not even in memory, because there are moments in time that are not knowable.

– Amitav Ghosh, The Shadow Lines

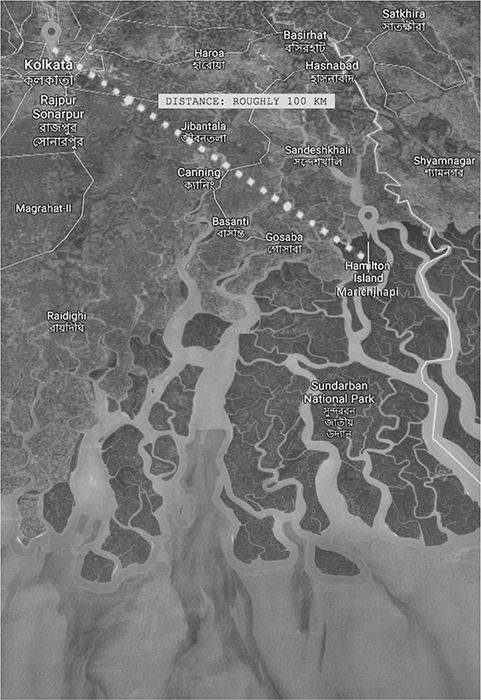

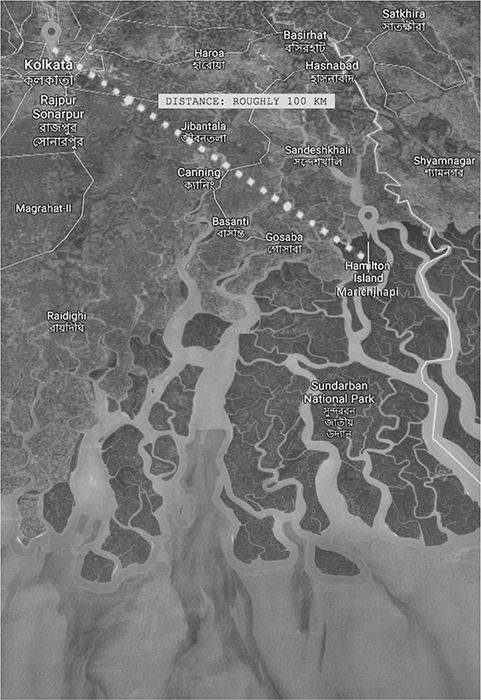

Marichjhapi is an island in the Sundarbans, located about seventy-five kilometres east of Kolkata. In mid-1978, around 1.5 lakh Hindu refugees, mostly belonging to the lower castes, came to settle here from refugee camps in central India. Some were driven back to the camps they came from, while the remaining managed to slip through police cordons and reach Marichjhapi.

Source: Google Maps

In less than a year, they transformed this no man’s land into a bustling village. There were rows of huts, a fishing co-operative, a school, salt pans, a health centre, a boat manufacturing unit, a beedi-making factory and a bakery, with money pooled from their individual savings and some help

from writers, activists and public intellectuals sympathetic to their story.

The West Bengal government extended no help.

By May 1979, the island had been cleared of all refugees by the Left Front government. Most of them were sent back to the camps they came from. There were many deaths during that period as a result of diseases, malnutrition as well as violence unleashed by the police on the orders of the government. Some of the refugees who survived Marichjhapi say the number went as high as 10,000. Marichjhapi could have been a shining example of the entrepreneurial spirit of a band of Bengali Dalits. Instead, it has become a forgotten story of one of the worst pogroms of post-Independent India, bigger than the 1984 anti-Sikh riots in Delhi or the 2002

anti-Muslim riots in Gujarat for the sheer scale of the violence and the number of deaths and rapes.

Why such violence took place is what this book tries to find out through the voices of those who were part of the Marichjhapi tragedy. But before we come to Marichjhapi, let us go back to the beginning – the Partition of Bengal that caused Bengalis to move from various districts of East Pakistan to Calcutta, from where they were packed off to refugee camps in central India.

Bengal, Interrupted

Bengal was divided twice. On 16 October 1905, the eastern, predominantly Muslim areas were separated from the western, largely Hindu areas.

Though the then-Viceroy of colonial India, Lord Curzon, stressed that Bengal was being divided in order to secure administrative efficiency, it was inherently the colonizers’ divide-and-rule policy aimed at separating the people of Bengal on communal lines.

While the Hindus (who belonged mostly to business and landowning classes) complained that the partition would make them ‘minorities’ in a province that also comprised Bihar and Orissa, the Muslims generally supported the division as they felt used by and inferior to the Hindu businessmen and landlords in west Bengal. Moreover, most of the mills and

factories were established in and around Calcutta, though raw materials were sourced from east Bengal from lands mostly worked upon by Muslim labourers.

In 1906, the Muslim League was formed in Dhaka to give Indian Muslims a political voice. The Partition sparked a severe political crisis with the Indian National Congress beginning the Swadeshi movement, which saw the large-scale boycott of British products and institutions. Due to such political protests, the two parts of Bengal were reunited on 12

December 1911.

Then came another partition, not on religious but on linguistic lines.

Hindi, Odia and Assamese areas were separated to form different provinces, with Bihar and Orissa in the west, and Assam in the east. The administrative capital of British India was also shifted from Calcutta to New Delhi.

The scars from the first partition never quite healed and they were violently raked up during this second partition of 1947, creating wounds that festered.

In August 1947, when the British finally left India after nearly 300

years, the subcontinent was divided into two independent nations, again on the basis of religion: Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan.

Thus began one of the greatest migrations in human history as millions of Muslims moved (or were forcibly moved) to West and East Pakistan (now known as Bangladesh), while millions of Hindus and Sikhs headed in the opposite direction.

The first wave that arrived in West Bengal were the upper caste Hindus and not the Dalits; the latter, firmly attached to the soil of their homeland for livelihood, did not leave their homes as swiftly as the upper caste Hindus.

Another important premise is that Muslims and low caste Hindus had little animosity. This was primarily due to the fact that they faced the same economic exploitation under the ruling upper class Hindus. They not only shared the same occupation, but also had the same lifestyle, language and

cultural fabric. To upper caste Hindus, both Muslims and lower caste Hindus were equally untouchable.

The academic paper ‘On the Margins of Citizenship: Cooper’s Camp in Nadia’ by Ishita Dey says that the significant years of refugee influx in the east (from East Pakistan to West Bengal) were 1947, 1948, 1950, 1960, 1962, 1964, 1970, whereas in the western region (from West Pakistan to North India), it was over by 1949. She writes:

According to official estimates of the Government of West Bengal, in 1953, 25 lakhs have been forcibly displaced. In 1953-61 there was no major influx but the figure swelled to 31-32 lakhs up to April 1958 and later in 1962 around 55,000 persons migrated after killing of minorities in Pabna and Rajsahi.

Approximately 6 lakh people crossed border between 1964 and 1971 and following the disturbances after creation of Bangladesh there was a massive exodus of about 75 lakhs. It was reported by the Minister of Supply and Rehabilitation, Shri Ramniwas Mirdha in a Lok Sabha debate in 1976 that 52.31 lakh persons migrated from East Bengal to India from 1948-1971.

This massive influx virtually broke down the administrative machinery of the West Bengal government. Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy, the then-chief minister of West Bengal, in a statement in the Assembly on 28 September 1950, said that mere provision of shelter for refugees was not enough. What his government repeatedly emphasized was lack of space, lack of resources and lack of aptitude on part of the refugees to adapt themselves to new conditions.

On 14 October 1952, the passport system was introduced and its announcement sparked another flood of refugees.

According to official records, the number was 3,16,000 in West Bengal and, including Assam and Tripura, went up to 5,87,000 within three years.

This group of refugees was also ninety-nine per cent Namasudras and low caste Hindus.

The refugees who came to India between 31 March 1958 and December 1963 had to give an undertaking that they would not seek any help from the government and, in addition, a citizen of India had to give an undertaking of their maintenance before a migration certificate could be issued. However, these restrictions could not check the inflow completely.

As for illegal entries into Indian territory, the total number of infiltrators came up to about 3 lakhs, according to a conservative estimate from unofficial sources.

Another heavy influx was witnessed between December 1963 and February 1964, following the disturbance sparked by the loss of Hazrat Bal from the mosque of Srinagar in Kashmir. The indiscriminate killings, rapes and looting at Khulna, Dhaka, Jessore, Faridpur, Mymensingh, Noakhali and Chattogram drove out more than 2 lakh refugees from East Pakistan.

Out of these, 1 lakh came to West Bengal, 75 thousand to Assam and 25

thousand to Tripura ( Jugantar newspaper, 7 April 1964).

How painful this journey was, emotionally and otherwise, is documented in Chapter 1 of this book through a nostalgic retelling of the migration to India from East Pakistan by rights activist Jyotirmoy Mondal.

Destination Dandakaranya

The new contingent of refugees, mostly Namasudras, were sent from temporary camps in West Bengal to camps in Dandakaranya, comprising parts of what are today independent states of Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. The Dandakaranya Development Authority (DDA) was set up by the central government to develop this mostly arid region by gainfully employing refugees in road construction work and for developing farmlands.

The region has been referenced in the Hindu epic Ramayana, when Rama, Lakshmana and Sita were exiled for fourteen long years. It was somewhere here, the ancient text tells us, that King Ravana’s sister

Surpanakha met Rama’s brother Lakshmana and fell in love. When he snubbed her and cut off her nose, a long battle followed that ended with Rama killing Ravana.

The lakhs of Bengali refugees who were sent here fought their own battles with sweltering summers and freezing winters, uncultivable land and natives who spoke a different language.

Some adapted to the conditions over time and made this region home; like sixty-four year old Kalachand Das who was sent to Mana Camp in Raipur and never left. Marichjhapi was a misadventure, he maintains (Chapter 6).

Others pined to return to West Bengal where there were fellow Bengalis who shared the same language and culture. Some recount the hostility of camp officers and natives, as well as the unfavourable living condition in

the camps (Chapter 6).

The Left Betrayal

When the refugees were being packed off to various camps in Dandakaranya, the Left parties who were in opposition in West Bengal demanded that they be absorbed within Bengal itself. In the course of my interviews with the survivors of Marichjhapi, many have told me that Jyoti Basu – who went on to become chief minister for twenty-three uninterrupted years (1977-2000) – himself had given speeches advocating the West Bengal government to do the same. Many Left leaders, most notably Ram Chatterjee, went to visit the refugees in Dandakaranya and assured them that they would be back in Bengal when the Left comes to power (Chapter 8). The refugees, naturally, thought the Left was their ally.

In June 1977, the Left Front came to power but, surprisingly, no one from the government seemed interested in following up on the promises made earlier to rehabilitate the refugees in West Bengal. Many desperate refugees, after waiting for some time, sent a memorandum to Radhika Banerjee, who was the relief and rehabilitation minister of the Left Front government at that time, on 12 July 1977. They said if the government

didn’t do anything to bring them back from Dandakaranya, they would be compelled to return on their own.

Marichjhapi and murders most foul

Out of despair, sometime in March 1978, more than 1.5 lakh refugees from different parts of Dandakaranya left for Hasnabad railway station in Bengal.

As soon as they reached Bengal, the police forced them down from trains and made arrangements for sending them back to Dandakaranya, though the attempt was not wholly successful.

Ignoring the hostility, thousands of men, women and children reached Marichjhapi island on 18 April 1978. More would join them in coming months.

So how did they come to know of an uninhabited island in the interiors of the Sundarbans? Some accounts say that Left leaders themselves had shown the island to the refugees when it was still in the opposition in Bengal and the refugees were in Dandakaranya. Others insist the refugee leaders discovered the island as they explored the Sundarbans for a place to make their own. A part of the Sundarbans lies in Bangladesh and this may

have drawn the refugees to the place (Chapter 6).

Nestled in the Gangetic delta, the Sundarbans happen to be the largest mangrove forest in the world, straddling India and Bangladesh. It is, in fact, a UNESCO-declared world biosphere reserve. What makes this unique ecosystem even more special is the fact that the delta is formed by the confluence of four mighty rivers – Brahmaputra, Ganga, Meghna and Padma.

With no help from the government, the refugees transformed the

nowhere land in the Sundarbans into a thriving village ecosystem (Chapter

6). But, by May 1979, they were driven out by the police who allegedly set

fire to 6,000 huts on the island. Nobody knows how many survived the carnage. In between, most notably during an economic blockade in the latter part of January 1979, refugees alleged that the police attacked the islanders repeatedly on instructions of the Left Front government.

When I spoke to Kanti Ganguly (Chapter 8) and read accounts, in the Statesman, of Amiya Kumar Samanta, Sundarbans Superintendent of Police, who oversaw the operation of cleaning Marichjhapi, I got to know that ‘less than ten’ people died on that island. However, all survivors I spoke to put the number of deaths to anywhere between 5,000 and 10,000; some said even more. Why such a wide gap? One reason is though the Bengali press sporadically covered the Marichjhapi story, the island is so far away from mainstream Calcutta and so difficult to access that what happened in Marichjhapi can only be reconstructed as oral history.

On 17 May 1979, Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, the then-minister of information, declared at Writer’s Building that Marichjhapi had been cleared of refugees.

Cause of carnage

Why did the Jyoti Basu government forcibly evict Marichjhapi settlers? The official reason is that Marichjhapi is a protected island and the refugees were destroying the ecology by cutting trees. There are, however, allegations against the government of caste bias as the refugees were mostly Dalits. Some say this is an example of how Bengal’s bhadralok Marxists, who talk about a classless, casteless society in seminar halls and political

speeches, display their inner caste prejudices (Manoranjan Byapari, Chapter

9). Others say the Left Front government thought these settlers would vote

against them as they had gone back on their word of bringing them back to West Bengal.

But nothing justifies the horrors unleashed on Marichjhapi’s settlers.

The real story of Marichjhapi is buried somewhere between manufactured lies and stifled cries. I revisited those I have known for years, met new people who still carry those old hurts in their hearts. Putting pen to my reporter’s notebook, I have written down fragmented memories of these women and men who got sucked into the Marichjhapi story.

1

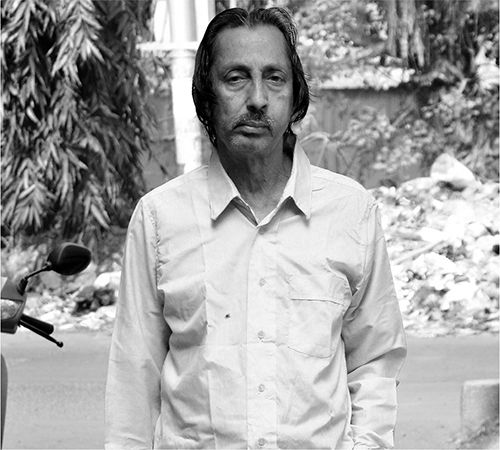

Jyotirmoy Mondal

Jyotirmoy Mondal saves witches. That’s a funny calling card for this nondescript seventy-something who has retired as a government bank clerk and has an actress for a daughter. But some lives will always be hard to decipher.

At eighty-four Gouranga Sarani, in a part of Kolkata not many would call genteel, Mondal puffs on his bidi as I prod him to tell me a story he has told me many times before. In my early days of journalism, when saving the world used to be a ‘thing’, Mondal was a source for many ‘human interest stories’. He travels into remote districts of Bengal to help widows who are branded witches by families and neighbours with an eye on usurping property. He doesn’t help them because he wants to sit on a dais, or for awards or to be on TV shows, but because he had promised himself after Marichjhapi that he would fight for those who do not have the means to fight off the ferocity of men. In my quest to document the oral history of the people of Marichjhapi, Mondal’s is the first stop.

There is hardly a more engaging narration of the trials of the refugees in Mana and other camps in the Dandakaranya region than Mondal’s accounts.

He takes me back to the beginning of things, when he was but a child and his father was fleeing from one country to another to save their family. It was 1956-57 and hundreds of thousands of masons and farmers, fisherfolk and potters, land owners and the landless, came to be referred to by a single word: ‘udbastu’, refugee. He tells me the story of a father and son, Sukhchand and Sachin, who lost everything in the process. He begins thus: A stranger offers a chillum to Sukhchand. Sachin, eyes heavy from the day’s exertions, takes in one of life’s most profound lessons – respect the

fellow traveller even when he looks as hopeless as you are – stranded behind the engine room of a steamer, going to a land he has never been to, to make a home that may never be.

It is an elaborate act, comical even, that Sachin watches as the small man holds out the earthen pipe with his right hand, with his left palm touching his right elbow and bending forward towards his father Sukhchand. In their part of Bengal, Kadambari village in Faridpur zilla, the part they are leaving behind and what is now another country, this is considered a gesture of respect, Sukhchand would tell Sachin later.

That night, in that dark, dank space where men snored and women sang lullabies to put babies to sleep, Sachin misses a man with a head full of unkempt white hair, an untrimmed snow white beard and dry skin on his arms and legs, like scales of a dead fish. His grandfather Gayali. He misses hearing Gayali call him ‘bhai’ in an attempt to wish away the two generations of gap between them and become friends. Sachin runs his eyes one last time from father to stranger and stranger to father as two men take solace in their deep drags. And then, in that borderland between sense and sleep, his mind traces the distance they have covered during the course of the day.

In his sleep, Sachin swims back to the shore, to their village that sits by the river Madhumati. There, under the shade of big trees, is Gayan’s house.

And Koitha’s and Dhalis’ houses. And the village wise man’s, the one who had warned against such a long journey. The madman’s house, where not everyone is mad. The Dhalis next door make battle shields that stop spears thrown from afar and break swords into two.

On the riverbank, on a relatively dry patch of land, is the local market.

Large round tin pots with fishes wriggling inside, the fresh catch of the day, are found here, sometimes the famed hilsa of the Padma river. And sugarcanes, jackfruits, mangoes, tortoises, all put out for sale. A bustling bazaar.

It is in this bazaar that Sachin had cried for the ripe green guavas that Gayali had refused him, saying something about the monsoons and stomach

problems and instead bought him Madan Kut Kutis, small jaggery lozenges that make ‘kut-kut’ sounds when bit into.

Sachin’s father Sukhchand, who travels often, gets him an anna’s worth of lozenges when he comes back from the village school where he teaches.

He couldn’t get a university degree as all universities are far away at Madaripur, Faridpur or Dhaka, the last of which is three days by boat.

Sukhchand married in the year of his matriculation examination. His neighbours had advised against it, saying that marriage could wait: ‘The boy needs an education first.’ But Gayali wouldn’t let go of the girl. Where would they find such a beauty for his long-faced son? So Sukhchand got married, took his exam and failed. The next year, however, he sailed through. ‘Our new bride Ranga-bou brings good luck,’ said Gayali. Sachin was born soon after. With two sons, two daughters-in-law and now a grandson, the widower Gayali could not have asked for more.

Sachin thus spends his days in the laps of loving parents and grandparents and the shade of the banyan tree that has outlived his forefathers and will live some more. But a shadow soon falls over Sachin’s idyllic world.

The riots are a rumour at first. But when the village headmaster, the man whose word is gospel across ten villages, falls to a traitor’s sword, Sukhchand wonders if this is the end of their peaceful days. The headmaster had gone to stop a riot in the next village and tell the Hindus and Muslims, many of whom had been his students, not to kill each other for the sake of religion. The killings stop but when the old man was on his way back, someone, who Sukhchand describes as a snake in the shape of a man, hacked him into two. As the headmaster and two of his young students fall,

‘Jai ma Kali’ and ‘Allahu Akbar’ war cries fill the night sky like venom spreading into arteries. Ram-dao, daggers, swords and tridents are out.

Sukhchand has been away for a long time. He comes back just before Durga puja, and Gayali asks him what had kept him away. His breathing gets

heavy. This is a question Sukhchand would rather not be asked, as it would prompt an answer Gayali would rather not hear. Sukhchand has decided to leave Kadambari; leave East Pakistan and cross over to that new country they call India. Just the name itself is a cuss word here, but this country is no longer safe for Hindus, for his wife and Sachin.

It would be their last Durga puja in the village of their forefathers.

Dark clouds hover over the village. There is a shadow of despair in Ranga-bou’s eyes. Gayali tries in vain to keep the storm inside in check, but little Sachin will not listen to reason. He runs into his grandfather’s arms, crying and pleading him not to let them go. The old man looks away.

Outside, it rains heavily.

Sachin watches as the boatman loosens the rope that ties the boat to the ferry and, with the precision of a village acrobat who has learnt how to walk on a rope without batting an eye, he jumps into the boat, steadies it and lets it sail.

The village has come to see them off. The two sisters-in-law wave goodbye to each other, eyes crimson with crying. Gayali, still fighting tears, cries out: ‘Sukhchand, it is a long journey, baba. Be safe, son. Take care of Ranga-bou. The little one has a bad stomach; take good care of his diet.

Take care, my son.’

Kadambari fades into a blur, then Kochuchushi bill and Chitalmari khal.

They reach the bank where steamers are lined, and it is in the crowded engine room of one such steamer ferrying passengers from one Bengal to the other that Sachin and his family find a place next to the small man smoking his chillum. As his father shares a smoke with the stranger, a blind man sings:

‘O Lord, why did you tear my land apart,

Why did you snatch my peace!’

Sachin sleeps.

The year is 1957. In front of Sachin is a sea of heads and hands carrying broken lives in bundles, getting off rusty steamers. Khulna jetty is a busy thoroughfare. Men from makeshift hotels come looking for customers.

Sellers sell knick-knacks. But Sukhchand has no time to waste; he tells his wife and son to hurry. It is a long journey from that point to their destination. Under the glare of a merciless sun, they walk to Khulna station.

On the way, Sachin sees a city for the first time. Giant tortoises without mouths, moving on paved roads. They call them cars here. Women in footwear look at men in the eye and share a laugh. Ranga-bou, not used to seeing women in fancy chappals, blushes and looks away.

Green-coloured trains are taking people to Calcutta. Barishal Express is transporting hilsa, hope, people and memories to stations unknown. The Madhumati hilsa is a big hit on the other side, someone says. They ride the train to Benapole, where they find policemen in droves, checking migration papers and keeping an eye on who is taking away more than they have declared. Many are without papers, praying they won’t be found out, but no one can escape these policemen. Men are being forced out of compartments. Some are allowed to remain inside after offering bribes but they are pushed around, their belongings rummaged, their gold and silver taken away, and their women eyed with greed. The law takes its course!

Cops in blue caps and khaki overalls approach Sachin’s father. Sachin has never seen cops before. ‘Why are grown men wearing school uniforms?’ he wonders.

‘How much luggage are you carrying?’

Mild-mannered Sukhchand fumbles for a reply to this as one of them dips his hand into the pitcher to check if there is money or jewellery hidden inside the rice. ‘Only grains, it seems.’ They laugh. ‘But you are carrying more luggage than you are entitled to,’ says one, eyeing Ranga-bou. These are not human eyes. Sachin has seen such eyes before; these are the eyes of an animal on prowl. Fear grips his child heart.

Sukhchand quickly fishes out thirty crumpled rupee notes which the men pocket, stamping their border slips and deboarding. The train leaves Benapole.

Lush green fields; lazy, grazing cattle; trees, named and unnamed; ponds, filled and dried up; sweaty farmers; and busy bazaars pass by.

Memories muddle up in Sachin’s mind. Gayali must be in the field now; it’s the season of harvest. Has he taken the day off, grieving their departure?

Sachin never saw his grandmother, but his grandfather showered him with all the love in the world. His big arms were Sachin’s nest during infancy.

There is a lump in Sachin’s throat as the train reaches Haridaspur. It is a long haul. An hour later, they cross an overbridge and a signboard next to it says ‘No Man’s Land’. The day gets hotter, and the men inside the compartment grow restless, as another sign flashes by, ‘Welcome to India!’

They are almost there. Sealdah station is now a wish away. They are in India.

Sukhchand comes out of his tent to face the fading sun. He has not been keeping well for some time. The vaccination injection at the Bongaon rail station has left him nauseated. He stays up coughing at night as the small bulb flickers over his head, hearing couples grunt and babies cry from other tents. Privacy is a foreign concept.

They have been here for a few days. Their names have been registered in fat files and temporary arrangements have been made outside Sealdah station for refugees waiting to be transported to relief camps near and elsewhere. Ranga-bou cooks their meals on the footpath, laying out bricks to make an oven and using twigs to start a fire. The pitcher of rice they have carried with them is emptying fast.

There is a two-rupee cash dole for every refugee daily. Sukhchand gets five rupees for the family. ‘It’s a beggar’s life here,’ he spits out. Who knew India would be such a depressing tract of fatigue and failure! He sees only despair and death all around him. Sukhchand looks at his wife – so full of life despite the travails – then looks out into the distance at the hope that is Calcutta. Is it a city or a mirage?

A week later, they are told to move again. The Jogeshwar Dihi transit camp is to be their new address. They board a train crowded with their kind; Hindu refugees in hundreds, trying to find a footing in a new land. There is not a single vacant seat inside. Ranga-bou and Sachin sit on the steel suitcase they are carrying, while Sukhchand stands guard. A baby wails from the seat in front of them. The mother looks around helplessly at the vacuous eyes of men around her and then, in a move practised to perfection from years of travelling amongst strangers, she uncovers a breast to feed the child.

‘Where are you from, sister?’ someone asks her.

‘Gopalgunj,’ she replies.

‘That’s where my parents stay!’ Ranga-bou exclaims. The woman’s name is Aaynamoti, and it turns out that she knows Ranga-bou’s family.

She tells Ranga-bou that her parents haven’t left the country. She is a chalice of youth; even such a long and trying journey has not broken her spirit or wiped her smile. Her husband, Akhil, keeps glancing at her as he chats with Sukhchand. The train chugs along.

Jogeshwar Dihi transit camp, Post Office Koichor, Burdwan zilla, West Bengal, is a small village with tents arranged around a big banyan tree.

Nearby there is a large pond filled with lotuses. Red earth is laid out like a dusty carpet for new visitors who have come here after a night’s journey by train, a halt by the riverside and finally a lorry ride.

Koichor bazaar is held on the other side of the lake twice a week in the mornings. Local vegetables and fish from nearby ponds – skinny and tasteless, unlike the ones from Padma – are sold in rotund pots. The only saving grace is the dheki shaak that Ranga-bou has found growing amongst the wild vegetation around the lake. That and boiled rice, on the first day at the camp, after several half-fed days is king’s meal for Sukhchand.

In a patch outside their tent, Ranga-bou plants the bottlegourd seeds she has carried all the way from their village. Turning a tent into a new home

takes up most of her time. Sukhchand is now the teacher of the camp.

Classes are held around the banyan tree. ‘Rabi Thakur took classes like this,’ he mutters to himself and smiles. No chairs or tables; only a stool for Sukhchand and a blackboard, propped up somehow. He teaches the alphabet, multiplication tables and some geography to the camp’s children.

To keep the flock together, he dilutes his lessons with tales from the lost land.

By teaching camp students, Sukhchand starts earning seventy rupees a month. His hope that there would be some relief at last is in vain as a strange illness comes to visit them. People begin to suffer and die of a peculiar fever. After much outcry, with two babies and an old man dead, a city doctor finally comes to examine the patients. Are lives so cheap around here?

The doctor seems to be a quack. His white pills and red tonic is unable to stop the deaths. Gloom has descended on the camp. Akhil has died, leaving Aaynamoti and their child at the mercy of uncertain fate.

A year passes by. Ranga-bou is with child again. The feeble sapling she had planted outside their tent is beginning to take the sturdy shape of a tree.

Other families have grown vegetables around their tents, pumpkins and chillies, onions and gourds, in an attempt to camouflage the barrenness of their refugee lives. It is time for the ten-armed goddess Durga’s arrival.

Sukhchand is now the camp headman. He makes arrangement for pujas and collects what little the families have to offer as chanda. He is also the solution giver. Jogeshwar Dihi transit camp is a mini sea of humanity –

people live and die here, couples mate, marriages break, widows find solace in the willing arms of married men … Sukhchand hears every gossip and is privy to every argument. Nothing is too personal or too sacred for this herd of homeless border-crossers.

Sukhchand’s class has swelled. Two new teachers have been appointed from the village adjacent to the camp. There is a chair and table now, a roof above their heads and a bell to announce the beginning and end of lessons.

A proper school!

One day a boy asks Sukhchand the meaning of ‘refugee’. He had wandered into a locality nearby and, thirsty after a long walk, knocked at a door. When a woman came to the door, the boy had asked for water. She had looked at him with scorn, before turning back to tell her mother-in-law that he looked like a normal boy, not a refugee. Both women had laughed out loud.

‘What is a refugee, sir?’ he asks Sukhchand again.

‘By legal definition that may be borrowed from the United Nation’s 1951 convention, a refugee is a person compelled to leave his country of nationality as he feels insecure and is afraid of persecution of his life, belief and opinions in his native land.’ Big words, but Sukhchand repeats them for his young student, eyes watering. His pupil repeats the words after him. ‘By legal definition that may be borrowed from the United Nation’s 1951

convention …’

Sukhchand gets up from his chair, trembling. Men and women have gathered around him, circling the school. A farman has come. They have been told to move again. Trains are ready, the government babus have announced, to take them to Dandakaranya. The Dandakaranya project area is 7,678 square kilometres of land stretching from the districts of Koraput and Kalahandi in Orissa to Bastar in Madhya Pradesh. It is the same place where Rama was banished for fourteen long years. Now, camps have been set up for these Bengali refuges from East Pakistan. If they don’t move, the cash dole will stop.

‘Who are we?’ Sukhchand asks.

‘We are humanity’s leftovers,’ the crowd shouts back.

The babus quietly make their exit, but come back at night with men in khakis. They enter tents without warning. The refugees put up a feeble fight, and policemen answer back with lathis and teargas.

Lorries are waiting outside, which Sukhchand and the others are forced to board. In the chaos, leaders from Leftist parties appear from nowhere.

Sukhchand cries for help. This is temporary, they say, Bengali refugees will be brought back to West Bengal. They speak with conviction. ‘Comrades, we will ensure this happens soon. Refugees will be settled in the islands of Sundarbans. But for now, you will have to go to Dandakaranya.’

The stench of unwashed bodies huddled like cows herded for slaughter houses fills the trucks. Children wail, men and women sit seething with rage or sob, raw wounds dripping blackened blood in their unending ride across unknown lands. The trucks stop thrice a day near eateries and barren spaces for food and defecation. ‘They are transporting animals from one stable to another,’ says Sukhchand.

Days give in to nights, and nights turn hollow, yellow in an endless cycle before they reach another refugee settlement.

Malkangiri.

According to Valmiki’s Ramayana, Rama spent thirteen long years in these forests with his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana. It is from here that Sita was abducted by the Lanka king Ravana, which led to the epic war.

Camp babus greet them as they make their way to the tents. Like bored shepherd boys counting flock, the babus do a quick roll call. Refugees become numbers again. They are told they would get a cash dole here as well, but they would have to work. And if anyone tries to flee, the dole money for all would be reduced. ‘That is it for the day,’ a babu barks. ‘Go home, now.’

‘Home,’ Sukhchand lets out a laugh. ‘Home, indeed!’

It is dark and dreary. The only sound is the gurgling of the Tamsa river flowing over a bed of pebbles. Behind the tents, a thick forest blocks out

everything that lies beyond. This is the land’s end. Their new home: village number six, Malkangiri.

Work days begin early here. Sal trees, mahua trees, big trees, small trees and trees without names – they all have to be felled, bidi leaves grinded. If you grind a thousand leaves a day, you get two rupees.

To fell trees, they have to go deep into the forest. Bears come without warning; wild monkeys swoop down from high branches. A week into their arrival, a man is left badly scarred by an enraged monkey. He had gone too deep into the forest. There are snakes on the ground and tigers behind bushes. The men move in packs, watching each other’s back. The women cook, clean and pray for the men’s return, planting saplings around tents like old times.

‘Why didn’t tigers attack Rama or Sita? They spent fourteen years inside the jungle,’ a child asks his grandmother one day. ‘Who would have killed Ravana if tigers had attacked Rama?’ she answers with logic no one refutes.

Bribes are a quick currency to buy peace in Malkangiri. Sukhchand knows this is not how it should be, but they have to grease palms to get their dole on time; to grow crops, they have to bribe; and they have to pay up again if they want a doctor to visit the camp. It is as if one has to bribe to stay alive here.

Nights fall early in the camp. Tired to their bones, hungry lovers feed on each other and whisper into the dark, fearful of being heard. Their muffled lovemaking brings life to the camp as one more night passes into the void.

There is some commotion outside Sukhchand’s tent. Nabakumar’s mother is scolding him, using harsh cuss words, while some watch the drama with glee. ‘Why can’t you marry that woman you fuck every day in the forest?

Mukhpora, you think I don’t know what you are up to? How long will you

make me cook and clean for you with my old hands? All my life I have slaved for your father. Now he is gone but I have to work for you.’

Nabakumar sits next to her, cheeks flushed.

The colony knows there is something cooking between Paunder’s sister (Paunder’s sister has become her only identity) and Nabakumar. Paunder’s mother has complained to Nabakumar’s mother about their affair, angering the old woman. How dare the girl’s mother have the temerity to broach this topic with her! After all, she has the upper hand, being the mother of the boy. She has already decided to marry off her son to some other girl from the camp. She tells Ranga-bou she would talk to Sukhchand about this.

Ranga-bou smiles. Roopchand, the bard, sings:

‘Who are you that saves me every time?

Why can I not see you, make you mine?’

Aaynamoti hides a blush. Ranga-bou sees a hint of happiness on her face after many, many days. Aaynamoti had become a portrait of grief since she lost her husband to the fever, and Roopchand’s music has brought back life to her eyes. ‘Is there something brewing between the two?’ Ranga-bou wonders.

Old habits. Sukhchand has taken up teaching again. His salary is seventy rupees a month like before. He has chosen the shade of a big tree near the camp as his classroom. From here, you can look afar – beyond the river, below the hills. The tribals have their hutments there; they live on good, cultivable land. The rocky, barren land is where the camp has been set up.

Even when it rains, the land is unmoved. The men dig deep, removing pebbles and rocks both small and large. They employ every trick known to farmers to grow rice and sesame. They tend to this land like a mother trying to bring an ailing child back to health.

The tribals come to talk to them, but it’s a tongue they cannot fathom.

Short, dark men with angry eyes speak at length without making sense.

They scream, make faces and stomp on the ground. It seems that they are not happy with the farming activities of the refugees.

The next morning, half their crops vanish. Someone has, in the dead of the night, taken away the produce. Months of hard work has been wasted.

There is unrest in the camp; the lads want revenge. They want to cross the river and teach the tribals a lesson, but Sukhchand will have none of it.

They will take turns to guard the fields at night, he orders. This is not going to be an easy task. There is fear of a tiger, so they make fire and speak in loud voices to keep the beast away.

Poush Mela. Back in their Bangla, it used to be a season of celebration.

Here, too, Bengali refugees from nearby camps have set up a tent in the distance. Kobi Gaan is being recited all day. At night, they arrange a bioscope: Sitar Banabas, the banishment of Sita.

Sometime that night, Paunder’s sister goes missing. She never came back after watching Sitar Banabas. Paunder, Nabakumar and others go looking for her. Someone goes to find Sukhchand, who has been working in the forest. They fan out into the forest in groups of two. Where could she be?

A loud scream is heard. At a corner of the forest, inside a thick bush, Paunder’s sister lies naked with horror frozen in her dead eyes. Her lips have been chewed out, her breasts mangled and legs scratched. Uneven red lines run across her fair skin. A black pool of blood has gathered around her thighs; red ants swimming in it.

Paunder’s mother reaches the spot; she screams, her face contorted, eyes bloodshot, seething with cold rage. It deafens the men around her and jolts them into a murderous fury.

Feeble-limbed Sukhchand lets out a war cry. He picks up a lathi, others pick up whatever they can lay their hands on, and they rush at the babus who are on their way to the camp in a jeep. They see murder in the men’s eyes and leap out of the jeep, running for their lives. The camp office is set

on fire, along with the abandoned jeep. The men take down everything that stands in their way.

They do not know who killed Paunder’s sister – the tribals or these babus – and they do not care. They will avenge her.

Sukhchand has spent a month in jail. News of the camp violence travels east. The press comes to see him from Calcutta, journalists jot down notes in tiny notebooks as he speaks. ‘You are a hero in Calcutta, sir. Your picture is on the front pages of many newspapers as the leader of Bengali-speaking refugees in Dandakaranya.’ Sukhchand smiles indulgently. It is a smile he reserves for children in the camp school who do not know what they are talking about.

Some Left leaders have made the long journey to Dandakaranya; some of whom Sukhchand has met before when they were forced out of Jogeshwar Dihi transit camp. You should join our party, they say. We need leaders like you with us. Sukhchand smiles again. With so many important visitors coming to see him, the pressure to release him mounts. He gets bail.

Sukhchand comes out of his hut, smiling. These are good days. He has a beard from the time he has spent in jail, his salary has gone up and he has become a father yet again. More babus have been assigned for the ‘welfare’

of refugees. There are more frequent inspections, and more roll calls to check if anyone has gone missing. Doctors come often and put their stethoscopes in their ears at the sound of the slightest discomfort.

Sukhchand knows why their behaviour has changed: elections are nearing.

No one wants unrest at a refugee camp.

But even good days are treacherous. A week after the elections, on a particularly dark and gloomy day, eagles circle the camp and tribals descend like acid rain. They have not forgiven the violence of these talkative strangers on their land. These are weather-hardened men; men without fear

or remorse, who fight bears, tigers and snakes, and eat roots and snails.

These are men not to be trifled with. Yet, the refugees fight them with all the strength in their hearts. The red earth gets a few shades darker.

One tribal tries to enter Aaynamoti’s tent and Roopchand attacks him with his dotara. Anything can be used as a weapon. Suckhchand picks up a stick. Dholakaka has picked up his spade; Ranga-bou her kitchen knife.

There is blood.

That night, under a starless sky, camp residents meet as a crowd of broken limbs and bandaged heads. ‘Let us go away from here, Sukhchand,’

Dholakaka, the camp elder, says. ‘Even Pakistan is better than here.’ They talk all night. ‘Let us go back to Bengal. Decades have passed here. That is where we belong.’

There is a new government in West Bengal: the Left Front government.

Their government. They have seen known faces in newspapers. Faces of new ministers. Faces that had given them hope in days of distress. They should go back to Bengal now. ‘Let us go, Sukhchand.’

Months pass as they plan the perfect escape, carrying whatever they can in the dead of night.

The central reserved police had taken away a girl from their camp. Unlike Paunder’s sister, she had lived to tell the story of that night. They had taken turns to rape her, then dropped her back in the morning. The camp residents had gone to protest, only to be lathi-charged back to the camp. The men talk of Marichjhapi in the Sundarban islands. Some from other camps have already gone and were starting new lives in the heart of the Sundarbans.

Dronopal, Matri, Kanker, Dhamtari, Paralkot railway stations pass. They ride back to where they belong, joined by refugees from Mana Camp.

1978. Howrah station. A band of unsung men and women squat on the platform. They will wait here till promises are met. They will wait for the

ministers to come. Instead, there are flashbulbs and a flurry of queries: Why have you come back? And why in such large numbers?

What should Sukhchand tell these reporters? Should he tell them about Paunder’s sister, or about Sachin, or of the men who lost life and limb fighting tribals, or recount their failed attempts to make home in the most hostile of places? Instead, he mutters: ‘If we have to die, we die here. We won’t go anywhere else.’

He remembers what that leader had told him when he was in jail: ‘When you return to Bengal, five crore people will raise ten crore hands to greet you.’

Where were those hands?

The sun sets every day with their hopes dashed. The government for the casteless and classless margins, the new Left Front government, extends no support. Rehabilitation is a distant dream, and the dole has also stopped.

They march to Rajpath; a big procession of shabby men and women, half-fed, fed up with their fate. Khakis come and lathi-charge: ‘Go back, beggars! Go back to your camps.’

They are back at the station, their belongings packed into tiny bundles.

They will go to Marichjhapi by themselves, they decide, with cold resolve in their hearts. They take a late-night train to Barasat. Marichjhapi is a few hours from there, they have been told. There are cops at Barasat station, armed and watching them with narrowed eyes. Walking next to Sukhchand is a sadhu from Mana Camp, a man with eyes red from cheap alcohol. ‘Jai ma Kali!’ he roars.

They have neither the strength to go further nor the money to buy train tickets. Women sit down on the platform, arrange bricks in the shape of ovens, put dry twigs inside and make fire; the little ones are hungry. Some boiled rice will do. A khaki tries to snatch away a woman’s belongings, but she resists with all her might. He kicks her hard. Half-boiled rice scatters on the platform, and the woman recoils in horror. The red-eyed sadhu roars and pierces the policeman’s thigh with his trident. Drops of blood fall on the rice.

Sukhchand rushes out of the platform with Ranga-bou and the boys as teargas and lathis rain down on refugees. Screams and gunshots fill the night sky. They hide inside a field, shivering at night. They must move again.

Hasnabad. Here, homeless wanderers smell good earth after more than a decade in dry land. Small mud islands are spread out against the sea at a distance. They think of the Padma-kissed land they used to call home. But the day’s harsh sun dries up their dreams. Dholakaka’s wife, Roopchand and Aaynamoti have gone missing during the night’s violence. Some have been arrested. Some have gone missing. But more people are coming in trains. People like them; Bengali refugees from various camps in Dandakaranya.

They get on a train without any tickets, and cross Bagna, Kumirmari, Kolagachiya river and the much smaller Punjali, before getting down at a station where land ends and sea begins. They breathe deeply, filling their lungs with the salty air. Marichjhapi is a boat ride away.

But how will they hire boats? What will they eat in Marichjhapi? How will they build homes, till land and grow crops? Where will the money come from? Sukhchand decides that they will find work at their current stop, save money and then make their trip.

They spread out into the villages like beggars.

Sukhchand takes work as a tiller. He evens earth, removes pebbles and makes land fit to grow crops. The money is good. The landowner, Enamul Haq, pays him five rupees a day, which is enough to buy a full meal for the family. At the end of the day, he bends in gratitude as Enamul counts his pennies – it is important to show gratitude and keep the employer in good humour. There are too many hungry hands ready to snatch work from you!

Ranga-bou finds work at the local bidi factory.

With the little ones at her side, she leaves early in the morning and works till evening. The family meets below a big tree outside the station as

the day ends. There is not even a tin shed for cover. This is not the time for luxury, however; they have to save every penny. There are other trees around them, and other families below those trees. All are refugees from East Pakistan, runaways from transit camps, waiting to relocate to Marichjhapi.

Like locusts, the press follows them here too. They are making it to the front pages of Calcutta newspapers every day: ‘Refugee mother gets down from train. Dead child in arms. Not a tear on her face.’

Another says: ‘A body has been found hanging from a tree in Hasnabad! Was she was raped before she was killed?’ It is Aaynamoti.

One of the refugees, Upen, has been caught trying to steal money from his employer. He is sent to jail. His young wife has sold herself to her employer. Their little one has disappeared after that violent night at the rail station; will she ever find him? Yet, Upen is happy. When Sukhchand goes to see him in jail, he says this is a proper room after all, this lock up, and there is food. What more can he wish for? ‘But dada,’ he says, ‘take our people to Marichjhapi. I will join you when they let me out of here.’

Sukhchand looks at the wide expanse of the Ichamati. From a distance, he looks like a bag of bones encased in blood and dirt. He had been crouching behind bushes, crawling on all fours like an animal evading its hunter.

‘Roopchand, Ranga-bou, Sachin, Paunder’s mother, Dholakaka,’ he whispers sharply. The bushes by the river bed move ever so slightly. A few heads suddenly appear from nowhere, more ghost than human.

Boats float on Ichamati. The sky wraps them up in its night blanket. Up above, a few stars – too few – darken the sea some more. Suddenly, there’s a flash of light. Someone speaks into a mike: ‘Go back. Turn your boats. Go back or we will open fire.’ It’s the river police! ‘Section 144 has been imposed on this island. Turn back!’

‘Turn back and go where?’ Sukhchand screams. ‘Tell me. Where do we go?’

‘This is no time for argument. Go back or we will open fire.’

‘Where shall we go?’ Sukhchand shouts again.

‘Go back to Dandakaranya,’ replies the inspector. The police launch has come close to their boats; so close that Sukhchand can almost smell the inspector’s naked rage.

‘No, we won’t go back. We will go to Marichjhapi!’ Sukhchand jumps into the river and starts swimming.

‘Sukhchand was your father, wasn’t he?’ I ask.

Mondal smiles.

‘So what happened after you reached Marichjhapi?’ I prod.

Mondal looks out of the window into the darkness that has gathered outside his old house. I have known him most of my adult life, and have travelled with him to pockets of darkness I never knew existed. We have grown close with time, but he has never answered my queries about what happened in Marichjhapi; only how the band of 10,000 determined people reached there. What life held in store for them once they reached their dream island, he refuses to tell. Tonight is no different. His story stops where Marichjhapi begins.

‘Let that question be. Let Marichjhapi remain buried in my heart.’

November 2017, Garfa Kata Pukur, Kolkata

2

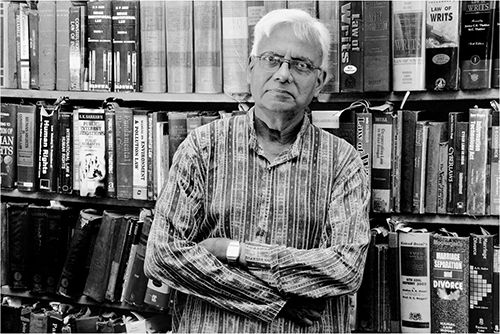

Safal Halder

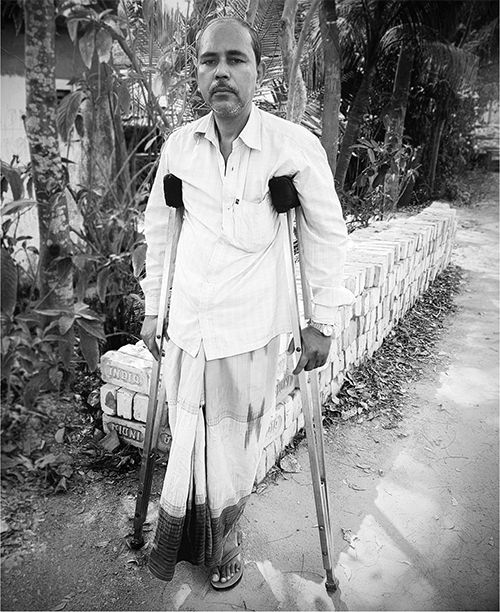

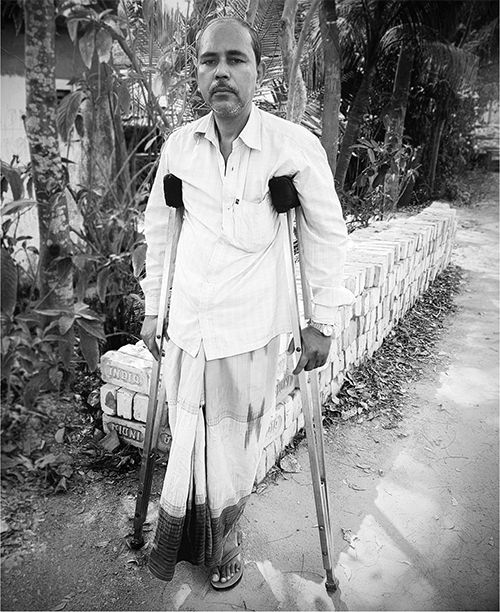

Iask Gouranga Halder if his name became Safal (meaning ‘successful’) after he swam through the night to reach the shore and report the horrors of Marichjhapi to the clueless citizens of Calcutta. The newspapers had once hailed Halder as a hero of his people, undeterred by fate or fatigue.

Today, the frail, asthma-afflicted, sixty-four-year-old can barely manage a smile between bone-rattling coughs and takes a pause before he can answer me.

‘No, I had the name from before.’ My question has triggered violent spasms in Halder. He spits out a mouthful of bile out of the window, sits down, lowers his head and parts his thinning hair with bony fingers. Two old scars criss-cross his pate like disputed boundary lines of neighbouring nations.

‘Did you get these scars when the police attacked you in Marichjhapi?’

I ask.

‘No, these are older ones,’ he says.

‘Tell me how you got them then.’

Halder flares up. ‘How many times will I repeat my story? Nothing has happened for so many years. After the massacre at Marichjhapi, we hid from the Left Front government’s goons. We stayed right under their noses by learning to become invisible. All we dreamt of was this government to

go away and a new one, one that doesn’t murder innocents, to replace it.

But even the so-called people’s politician Mamata Banerjee has forgotten us. The Marichjhapi case has not been opened. Who will pay for all those deaths?’

Dusk has settled outside Halder’s one-storeyed house at Purbo Palli, Kalikapur. The road outside leads to the Eastern Metropolitan Bypass that connects Ultadanga in the north to Kamalgazi, Rajpur and Sonarpur in the south, running a distance of twenty-one kilometres along the eastern rim of the city, along which high-rise buildings in glass and concrete have come up, transforming Kolkata’s skyline.

But this is a lower-middle class locality in the south of the city with skinny allies and thinning slices of post-Partition history still trapped in the memories of residents who made a new country home after an arbitrary line was drawn up to create East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.

Someone switches on a dim bulb, and tea is served with greasy sweets. I offer cigarettes to my photographer friend and Jyotirmoy Mondal, who have accompanied me to Halder’s house. We smoke in silence as we wait for Halder to collect himself and take us back in time.

‘I am from Lakhikhai village in Bangladesh’s Khulna zilla. I grew up amidst the growing tension between Hindus and Muslims. There was a riot in 1964. Hundreds left from my village. I must have been fifteen or sixteen at that time. We didn’t have birth certificates those days. I had lost my parents early and was staying with ageing relatives. They told me to leave while I could and start from scratch in the new land. I was already married and feared for the safety of my new bride. There were headless bodies on the road and limbless men and women hiding their horror inside dark rooms. But my matriculation examination was due. I waited to clear it before I crossed over to India, as it would be easier to get a job.

‘I got these scars when my wife and I were crossing the border on foot.

A group of Muslim men attacked us with axes. I asked my wife to run as I tried to hold them back. I was staring death in the face but I wanted her to be safe. Two sharp blows fell on my head. I lost consciousness and dropped

to the ground. They must have thought I was dead because they did not hit me anymore. Later, the group of men and women with whom we were travelling came back in search of me, found me still breathing and took me with them. My wife was in that group. I lost a lot of blood, but survived.

‘On this side of the border, near Calcutta, the golden words those days for people like us, homeless refugees from East Pakistan, were: “Daak ashbe”. This meant we would be transported from the transit camps set up at various places in West Bengal to the permanent Mana Camp in Raipur, now in Chhattisgarh but then part of Madhya Pradesh.

‘Mana Camp was not a single camp. It was a cluster of 500 or more camps of varying sizes. I stayed in a camp called Kurud.

‘It would be wrong to say camp life was only hardship. There were good days and there were bad days. The government gave us dole. We worked on roads. We erected buildings. We got paid. Our temporary tents became pucca houses over time. Our people got married, had children and lived the remaining days of their lives dreaming of a lost home. But somewhere, in the midst of all this, we were losing our identity as Bengalis.

There was a gnawing fear that if not our children, then their children after them would not speak our beautiful language.

‘The All India Udbastu Unnayansil Committee set up by us for the welfare of our people had been working tirelessly through the years, demanding more rights and better working conditions. The camps were scattered. The committee wanted to get people to stay together, to fight as a collective whenever there was any wrongdoing by the government babus in charge of the camps or the tribals who were very different from us.

‘Meanwhile, leaders from Jyoti Basu’s party, the CPI(M), had come to visit us at the camp a number of times. They assured us that as soon as they came to power in West Bengal, they would free us from the hills and forests of Dandakaranya and take us to the fertile plains of Bengal and give us a better life. We were naïve; we believed them.

‘Our camp leaders told us the refugee vote is important for the Left Front, so they would never desert us. But with no help from official quarters

when the Leftists came to power in West Bengal, our people started fleeing Mana Camp in groups and headed towards Calcutta.

‘In 1978, around five to seven families hired lorries to Raipur station.

From there, we took the train to Howrah and then to Sealdah. I had saved a modest sum of money, around Rs 10,000, from the years I had lived and worked in Mana Camp, 1965-1978. From Sealdah, we went to Hasnabad.

At Hasnabad, our people took temporary residence in houses of relatives or found work in local fields. We stayed there aimlessly for two months, deciding our next course of action and waiting for All India Udbastu Unnayansil Committee leaders to guide us. Meanwhile, news broke of refugees from various other camps coming to Bengal in large numbers and facing hardship. I was lucky I had saved money to see me through in those two months.

‘We had misjudged the situation in West Bengal. We thought Left leaders would keep their promise and rehabilitate us in the state after they came to power. We thought there would be land for us to build homes and fertile fields to grow crops. We should have known these were empty promises. Our committee leaders went to Writer’s Building to remind the government of past promises, but nothing happened.

‘Around this time, committee leaders came to know of Marichjhapi, an uninhabited island in the heart of the Sundarbans. There was a rumor that some Leftist leaders had showed them the island as a possible habitat for the thousands of refugees deserting camps and reaching Bengal. Others say committee leaders themselves had discovered the island during their excursions to the Sundarbans. I don’t remember the exact day or month, but sometime in the middle of 1978, we hired boats and set off for Marichjhapi.

‘Our dream home was a mud island filled with shrubs. There was a thick forest of useless shrubs and, unlike the rest of the Sundarbans, there was no plantation in the island. So it was a bloody lie told by the Left Front government that we destroyed a reserve forest to set up home in Marichjhapi. There was nothing to destroy!

‘Around 200-300 boats had reached Marichjhapi that day. I was in the first lot that set foot on the island. I felt like an astronaut on a new planet

after an arduous travel through space and time. Hundreds of boats would arrive here in the next few months. We cleared shrubs, evened land and began town planning in all earnest. The more intelligent amongst us made a site map for a village housing society; we called it Netaji Nagar.

‘Those were magical days. We slept in open fields under a sky full of stars. We lit fire around us to keep insects and animals away. During the day, we built huts from logs that we got from neighbouring islands. Golpata leaves were used to make thatched roofs. Residents of neighbouring villages got us food and other essentials, and we pooled in money we had saved during our Dandakaranya years. We learnt that Ramakrishna Mission and Bharat Sevashram Sangha wanted to help us but the government did not allow them. By this time, outsiders were becoming aware of our existence. We toiled night and day with limited resources and the will to make Marichjhapi our home. Social workers and public intellectuals like your father, Dilip Halder, visited us and gave us money to sustain ourselves.

‘We had our work cut out for us. I was not good at construction work, so I was made a messenger between mainland Calcutta and Marichjhapi.

My job was to carry letters to our well-wishers in the big city with a list of things we needed for the island. I delivered those letters and brought back money and material. In the months that followed, we set up a school and appointed a teacher from amongst us. A refugee doctor set up a dispensary.

I carried back medicines from Calcutta to stock up the dispensary.

‘In Calcutta, I used to stay at 136, Jodhpur Park, in the house of Subrata Chatterjee, a renowned engineer. This London-returned engineer travelled with me to the island many times, helped us in planning Netaji Nagar and encouraged us. He, and several others including poet Sunil Ganguly, held citizens’ meetings across West Bengal to highlight our struggle for existence.

‘Chatterjee told us not to trust the communists in power. “I hate these bastards,” he would say. “I have seen the ugly face of communism in soviet Russia. You should not rely on the government and build an island community on your own.”

‘And we did. Over time, the population of Marichjhapi swelled to 40,000 from the initial 10,000. It had become a functional village with three lanes, a bazaar, a school, a dispensary, a library, a boat manufacturing unit, and a fisheries department even! Who could have imagined that so much was possible in so little time? Maybe all those wasted years in Dandakaranya had given us superhuman will.

‘Obtaining drinking water was a big issue. Marichjhapi water was salty, so we had to travel to Kumirmari, the next island, by boats and bring water back in big pots. We had to ration water. When I told Chatterjee this, he came to the island, gave us money and told us how to build a deep tube well that would get us drinkable water from below the ground. This is the same tube well in which policemen would later drop a bottle of poison, killing many of us!

‘We were attacked thrice. Memory fails me now, but I do remember that the most horrific of the police actions on the island was the economic blockade when supply lines were cut off and we were left to starve without food, medicines and other essentials. Anandabazar Patrika journalist Sukharanjan Sengupta came to visit us a few times and heard our story. It was through his articles in Anandabazar Patrika that a wider population became aware of us, though that did not really help our cause. The government made every effort to stop NGOs and missionaries from reaching us. Only sympathetic private citizens escaped police patrol and came to us with money and essentials. That, too, stopped during the blockade.

‘My leaders told me I’d have to tell people in Calcutta how Marichjhapi has been turned into a police state. Letters were written for Chatterjee and others, folded, put inside plastic bags and handed to me. At night, I took out a boat and decided to try my luck. It was a crazy thing to do as police launches had surrounded the island. The idea was to slip through the launches as the policemen snored, and reach the shore. We had gone a little distance into the river when we came under the searchlight. There were three other boys with me. “Should we turn back?” they asked; I told them

there was no turning back. Since the letters were in plastic bags tied to our waists, we deserted the boat, jumped into the river and started swimming.

‘I do not believe it myself when I think of what happened that night, but we actually swam the river and reached Kumirmari. However, we did not know there was police presence there as well. A policeman came and started questioning us. He slapped me hard and asked me if I was from Marichjhapi. I lied that I was from Kumirmari and had gone to Marichjhapi to see what was happening there. I also badmouthed the people of Marichjhapi, saying that they should be left to die. The policeman let us go.

‘We did not rest. Sleepless and tired from hours of swimming, we walked across Kumirmari and took a boat to Satjelia village. We stayed the rest of the night there, woke up early and walked all the way to Canning.

The currency note I was carrying in my pocket had become soiled and useless, so all day I walked without food or water, and finally reached Canning. There, I had some food at a dhaba for free and boarded a train for Jodhpur Park without a ticket. In the evening, I knocked on Subrata Chatterjee’s door. It was 31 January 1979.

‘Chatterjee telephoned a journalist. I had no idea who was on the other side but I told the journalist everything. I told him I had letters from committee leaders with me, and that I would hand them over to him if he would publish our story. The man on the other side asked me to read out the letters to him. I did. I could barely keep my eyes open after that. Chatterjee asked me to rest and I fell into deep sleep. When I woke up next morning, I was a hero.

‘Chatterjee told me my story had been carried in the papers and that everyone knew of me and my people now. There would be pressure on the government to call off the economic blockade. That day, I went to several newspaper offices and showed the letters I was carrying with me. I also met Shakya Sen, a junior lawyer, on Chatterjee’s instruction and showed them to him. We stayed the night at Chatterjee’s house. Sen would later fight for us against the government in court.

‘I set off early next morning as one of the boys had to go to Taldi village to meet a relative. We had taken a couple of steps and were outside Jodhpur

Park post office when we felt we were being followed. Four men surrounded us. We got into a police jeep parked on the other side of the road and were taken to Jadavpur thana. We were questioned all day, after which they let my companions go. They knew I was the one the newspapers had quoted. I was kept in police custody for four days. On Day 5, I was sent to Alipore Central Jail, where I spent twenty-seven more days. I came out and went straight to Marichjhapi to a hero’s welcome. The economic blockade was over, thanks to the letters I had carried with me to Calcutta and the newspaper articles that came out because of them.

‘The next few months were a blur. I mostly stayed outside the island at my relative’s house, away from Sundarbans, and tried to find myself a job. I went back to Marichjhapi whenever I got time, even as a case carried on in the Calcutta High Court with lawyer Shakya Sen fighting on our behalf.

‘The newspaper articles and the court case against the government halted the economic blockade but could not alter our fate. Time and again the government sent goons in khakis to attack us, arrest our men and torture our women. People started leaving Marichjhapi in large numbers; some went back to where they came from, to the refugee settlement in Dandakaranya, while others travelled far and wide in West Bengal looking for new home.

‘Non-stop police action had demoralized islanders. One night, someone came and dropped a bottle of poison into the tube well. Thirteen people died the next day. Babies were dying like rats from diseases, and women were afraid to venture out for fear of being raped by policemen. There were several incidents of our boats being hit by police launches and sunk mid-river.

‘On 14 June 1979, it was all over for us. The police came, set fire to our huts and forced the remaining ones out of the island. It was the end of the Marichjhapi dream. One year of dying by the dozens, yet carrying on with fire in our souls.’

‘What happened to you after that?’ I ask Halder, who has tears streaming down his face.

‘Luckily for me, I was not on the island that day. I had shifted to my relative’s place with my family as I knew the island was doomed. I feared for my wife’s safety as women were being taken away by the police. When I heard what happened, I sank into depression. For twelve months, we had strived to make a shrubby island into a home for the hopeless. Our lobster business had been turning into a big success. If only we could have waited for two more months, the time spent in cultivation would have borne fruit and we would have sold those lobsters at markets in Calcutta for big money.

But that was not to be. Everything was destroyed in the island, razed to the ground, burnt, made impure.

‘After a while, I shifted to Chatterjee’s house in Jodhpur Park. The mezzanine floor was empty. I stayed there with my wife and her parents.