Step 5

Undertake Fol ow-up Activities

and Evaluation

Evaluation must be planned in advance and carried out throughout the duration of track II processes. The benefits of evaluation are not limited to the latter stages of a project. Assessment and reassessment of goals, documentation of all activities (what was done, by whom, and with whom), and outcomes (both successes and failures) are actual y beneficial throughout a project’s lifecycle—from the planning stages, through project implementation, and after a project concludes. Even if evaluation is carried out formal y only at the end, the degree to which goals are established and change strategies are made explicit initial y will make evaluating the program at the end easier and more effective. Similarly, follow-up activities—such as scaling up the impact of an initial y limited project—are more likely to be fruitful if they are worked into the project’s design from the beginning.

Plan For and Initiate Follow-up Activities

If changes accomplished in any track II process are to be maintained and implemented, follow-up activities, actions, and in some cases institutions must be explicitly planned for. What is called the “reentry” problem makes it difficult for participants to maintain their newly developed relationships and more conciliatory attitudes toward the other side when they leave the process setting and go home to their communities, which maintain a much more hostile stance toward “the other.” If the positive attitudes and behaviors are to be maintained, or better yet transferred further, frequent reinforcement needs to take place—either through continued cross-group contacts (emails, phone calls, letters, visits), follow-on joint projects, or fairly frequent follow-up meetings.

Similarly, if plans are made to implement follow-up activities, these need to be set in motion before people leave, and explicit responsibilities, dates, and “deliverables” need to be specified. Even then, it is often hard to keep the interest, excitement, and momentum alive once the group goes home—so frequent follow-up cross-group contact is vital y important. The continuing process of developing plans for follow-up meetings and for work to do between those meetings can also help keep momentum going and interest in peacemaking alive. The key is to keep people engaged with the process—and the cross-group contacts they have formed—after the process ends. If action is not taken frequently to maintain dialogue and engagement, the process will wither as people become increasingly distracted by their day-to-day business and as the memories of the relationships made and ideas developed in the workshop or dialogue become less and less current or important in their day-to-day lives.

Document the Activity Thoroughly

Another important aspect of follow-up is documentation. As noted earlier, evaluation is best done throughout the intervention process. In practice, however, evaluation, if it is done at al , is typical y done at the end. This is better than nothing, and a post facto evaluation can reveal a lot of useful information to the track II providers and others if the evaluation is made public. Even if a formal evaluation is not completed, documenting what was done, why (what was the strategy of change?), with whom, and with what outcomes is important for the intervenors and is likely to be of use to the participants and (if confidentiality rules permit wider distribution) to outside observers.

In addition to offering practical lessons for future interventions, an evaluation of specific track II activities presents an opportunity to test the efficacy of those theories that may have guided (implicitly or explicitly) the intervenor’s activities. The link between the theories an intervenor uses and the intervenor’s evaluation of success is usual y ignored in the literature on evaluation.

The goal of most track II interventions is to have as wide an impact as possible. Some interventions focus on individual-level change, but even those assume that if one changes enough individuals, a wider benefit will also occur. If this is to happen, others must learn from the intervention’s successes and failures. For processes that are intended for wider audiences initial y, evaluation is even more important as more people are affected by the track II effort, and more is to be gained or lost through its success or failure. Thus, documenting what has been done, what worked, and what did not work for all processes is very important if track II efforts are to be as successful as possible.

Undertake an Evaluation

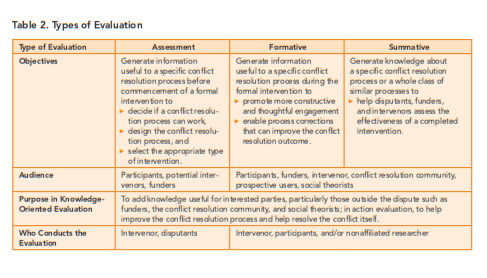

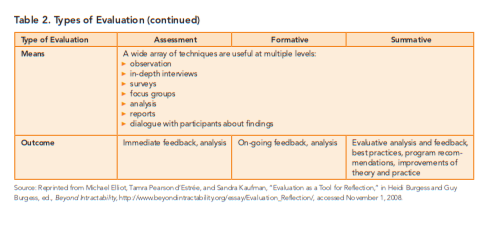

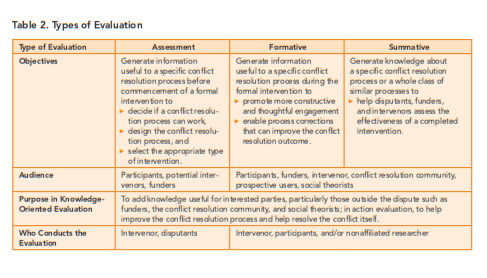

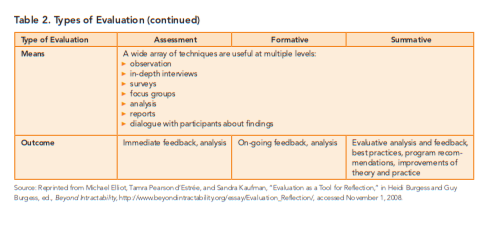

Track II intervenors need to decide early on what their goals are and what their level of intervention and particular process is going to be. Then they need to design an evaluation process that starts at the beginning of the intervention (or before, if one considers conflict assessment to be part of the evaluation). Care must be taken to match the goals of the evaluation to the goals and objectives of the particular process. Evaluations with goals that differ from the goals of the intervention can distract participants and lead to inappropriate critiques and conclusions. Evaluations using appropriate criteria, however, provide realistic feedback and guidance for constructive change—as the intervention is happening and at the end (for future interventions or follow-up activities).

Formative evaluation—the evaluation that takes place during an intervention—usual y involves a structured process of reflection on the intervention: the agenda, the procedures, and the outcomes so far. The purpose is to provide input to the intervenors about what is working well and what might be changed. It is usual y done by the intervenors themselves or sometimes with outsiders working in conjunction with the process providers. Common approaches include surveys of participants, reflective dialogues, observations, and interviews. Another useful approach is to appoint a project historian who can chronicle the evolution of the initiative, describing the stages through which it passes and (with due respect for the need for confidentiality) assessing what actual y happens before, during, and after specific activities.

Formative evaluation usual y improves the intervention process and maximizes the likelihood of beneficial outcomes. In addition, it promotes individual and social learning, increases awareness of what is working well and what is not, and continues to build relationships among participants and between the intervenors and the participants. This evaluation usual y does not happen unless it is explicitly built into the initial plan of the intervention, with funding and time explicitly allocated to such endeavors.

Summative evaluation, done at the end of an intervention, focuses on the overall effectiveness of the program. This kind of evaluation determines what worked well and what did not—what aspects of the intervention could be considered successful and which were not (and why). Measurement strategies include those of formative evaluation (surveys, dialogues, and interviews) as well as interviews with the intervenors and analysis of documents and media.

In summative evaluation, the definition of success is key and tricky. General y, success needs to be measured on the basis of the stated goals and at the appropriate level. If the goal of the process was simply to change immediate attitudes of participants, using a postintervention survey to assess attitudinal change is minimal y acceptable—and more valuable if a preintervention survey was taken as wel . Either way, however, attitudinal changes tend to disappear quickly once participants go back into their normal environments and resume their everyday activities, which is why a measure of attitudes several months or even years later may give a better insight into the long-term effect of the intervention.

If the goal was more than individual attitude change, then ways need to be developed to measure associated behavioral change and transference. Do the behaviors of the participants change over time? How? Are there other explanations for this change? How many of the ideas developed in the track II process were carried forward into a track I process? How many of these ideas actual y did get implemented? Such measurements get increasingly complicated the further away one tries to get from the original intervention—in terms of either time or people. Intervening or extenuating factors also must be considered. Before an intervention can be declared successful or unsuccessful, it is important to consider what other factors, beyond the intervention, affected the ultimate goal of the process—be it attitudinal change or “peace writ large” (i.e., not just the short term cessation of hostilities, but the remedy of underlying social tensions and attenuated relationships that led to the conflict in the first place).44 Although the details of evaluation are extensive, the primary issues and options are summarized in table 2.