The way these three elements work together can be explained

by an illustration, but before that I need to bring in some new terms, relating

to factors of production - the things that allow wealth to be produced

or made available. The major constituents are land: consisting of land

itself together with all natural resources; capital goods: goods that

are used in the production of other goods, consisting of all kinds of tools and

machinery and also working animals; labour: human effort used in the

production or making available of goods and services, including enterprise in

generating information and organising production.

An important point is that factors of production are

themselves forms of wealth - it is one of the reasons why wealth accumulates. The

implications of this are discussed in chapter 20 and examined in detail in chapter

97. Land and unrecovered mineral resources are sometimes excluded from formal definitions

of goods, where that term is restricted for things produced by human effort. I

prefer to regard them as goods even though they are not the product of human

effort because they are useful and have exchange values as do all other forms

of wealth. It is for this reason that the word 'generally' is used in the

wealth definition.

For simplicity I shall refer to factors of production as capital

wealth, using this term to denote both goods and services that are used to

facilitate the creation of other goods and services but which do not become

part of those other goods and services. Capital wealth does not itself sustain

or improve people's lives, but provides the means to achieve those ends. Also capital

wealth is used in creating other forms of capital wealth. Goods and services

that in themselves sustain or improve people's lives are known as consumer

wealth. All wealth is 'consumed' in the sense of being used up or degraded

over time, but for clarity when terminology matters I shall reserve the words

'consume', 'consumed' and 'consuming' to refer to consumer wealth, and the

words 'utilise', 'utilised', and 'utilising' to refer to capital wealth. I

shall use the general terms 'use', 'used' and 'using' when there is no need to

be specific.

A short digression is in order here. Mentioned above were

working animals in the economic context of capital goods, but I hope that most

people regard them as much more than that. We should take a moment to

acknowledge the massive debt of gratitude that humanity owes to working animals,

especially horses. Noble, strong and patient animals, they are ever willing to

apply their enormous strength to our service, however harsh, dangerous or

monotonous the circumstances. The help they and other animals gave improved

human lives and prosperity immensely for thousands of years, as they still do

throughout the developing world. Horses greatly amplified our power and speed,

and as a result have been central to the evolution of civilisation.

On Liverpool's waterfront at Mann Island there is a monument dedicated

to the working horse. It honours the horse's steadfast reliability and hard

work without which the port and commercial heart of Liverpool could not have flourished

as it did. Whenever I visit I make a point of paying my respects.

Figure 4.1: Liverpool's fine tribute to the working horse

by sculptor Judy Boyt. Entitled simply "WAITING........." Source:

Author.

Now at last we come to the illustration.

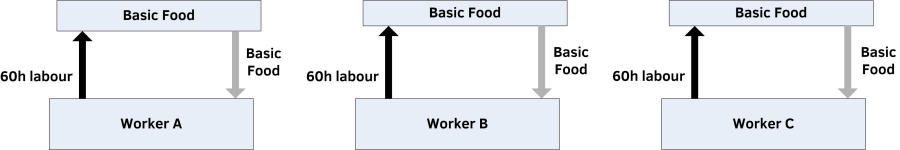

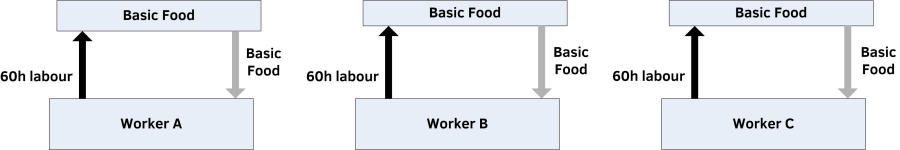

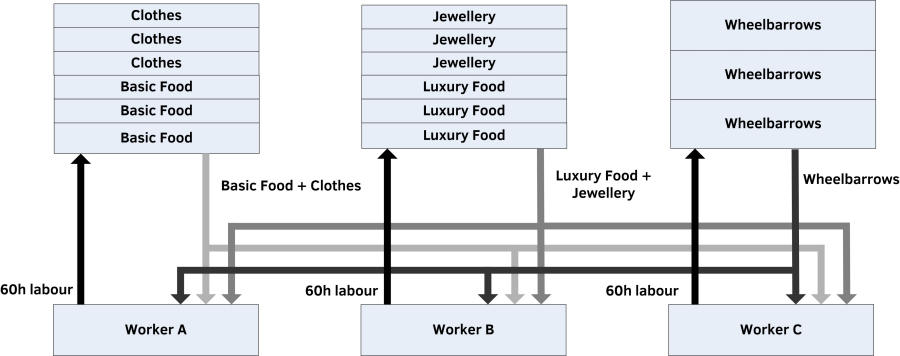

Let's say that in a (very) simple economy there are three

people, each working 10 hours for 6 days of the week to produce enough food. This

is a subsistence economy where there is no surplus wealth and no co-operation;

all work is devoted to providing for personal needs - survival wealth.

Figure 4.2: A subsistence economy

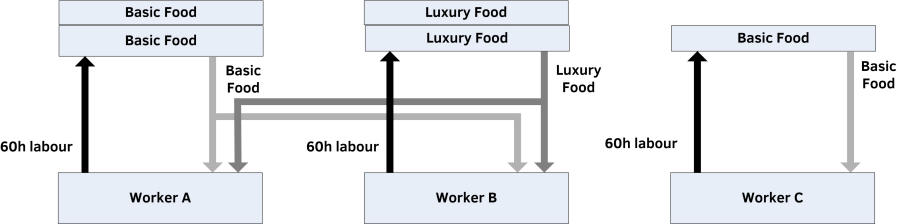

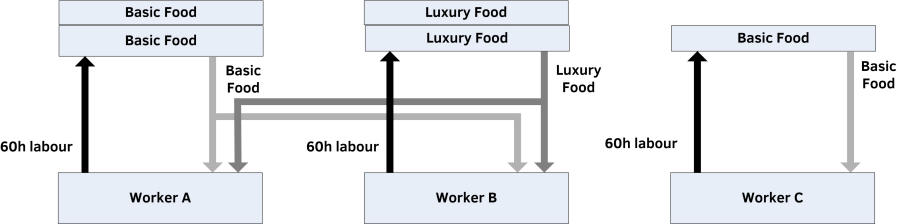

Worker A discovers a way to make a primitive knife using a

sharp-edged stone, which makes the harvesting of food twice as fast, thereby

doubling the rate of production. Now A is able to produce enough surplus wealth

in the form of basic food to supply B, so A persuades B to go further afield to

find the luxury food that they all enjoy so much, and bring back enough for

both A and B in return for basic food from A. Note that B is also producing

both survival and surplus wealth. B's survival wealth is the luxury food that

is traded with A for basic food, and B's surplus wealth is B's own luxury food.

This is illustrated in figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3: A uses a primitive knife to double production

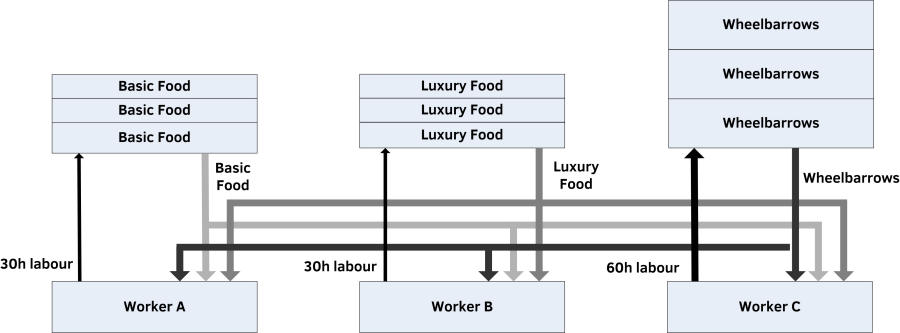

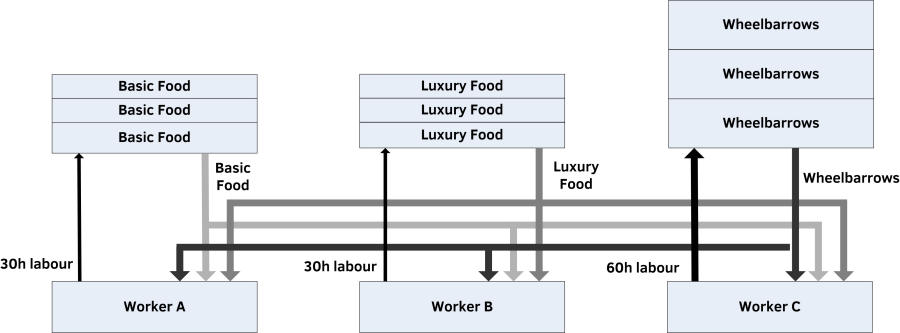

Worker C is now feeling a bit left out but unbeknown to the

others has been working on a device to speed up the production of all goods -

the wheelbarrow! The trouble is that the materials available mean that

wheelbarrows don't last long, so they have to keep being repaired and replaced,

which is almost a full-time job in itself. With 60 hours of labour each week C

can keep enough wheelbarrows in service for all three, noting that wheelbarrows

also speed up the production of wheelbarrows. C is initially happy to do this

in return for the same quantity of basic and luxury food that A and B get. Productivity

of both basic and luxury food is now enhanced a further threefold, so that A

and B only have to work 30 hours each week (60 hours each without wheelbarrows

produced enough of each food for 2 people, so a threefold production

enhancement would produce enough for 6 people in 60 hours, or for 3 people in

30 hours, which is what is needed). See figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4: Wheelbarrows treble production

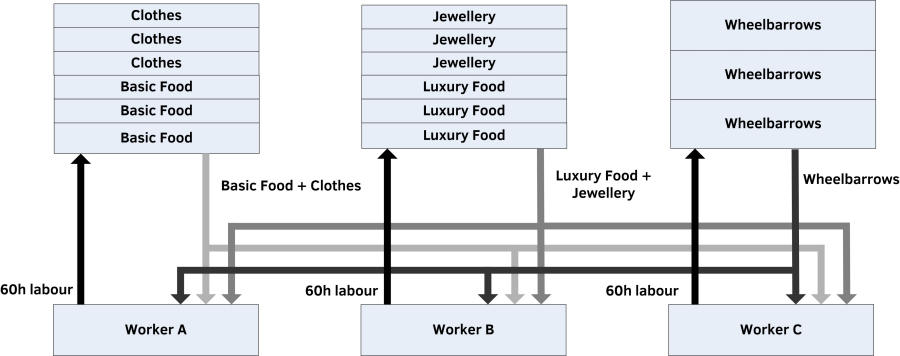

Now C again feels that things are not working out fairly, so

A and B agree to produce additional products, clothes and jewellery, and find

that by spending 30 hours each week at these tasks enough are produced for all

three people. See figure 4.5.

Now all three are spending 60 hours each week working, but

instead of having just basic food they now also have luxury food, clothes,

jewellery, knives and wheelbarrows.

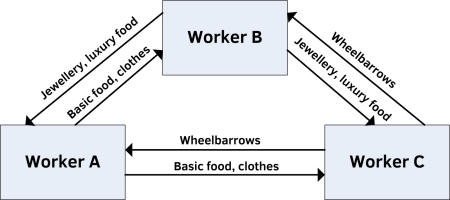

Figure 4.5: Full production in our simple economy

Although only A produces the means for all to survive (basic

food), all three are able to share all produce by trading what they produce - A

trades for luxuries and wheelbarrows, B trades for survival wealth, luxuries

and wheelbarrows, and C trades for survival wealth and luxuries. The surplus

wealth that A produces is everything apart from the basic food that is retained

for A's own use, and the survival wealth that B and C produce is that which

they trade with A for basic food.

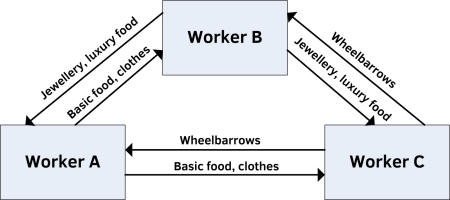

In this economy everyone both gives and receives wealth, and

the value of wealth they give and receive is the same. This can be illustrated

on what will be referred to as a wealth transfer diagram - a diagram

that indicates wealth transfers. Wealth transfer diagrams are useful in

indicating transfers without the distractions of money, which often complicates

the picture. A diagram that shows only money flows will be referred to as a money

flow diagram. The words 'transfer' in relation to wealth and 'flow' in

relation to money are chosen because wealth is produced and consumed (in the

sense of being used up or degraded over time) - it is transferred from someone

who creates it to someone who consumes it, whereas money merely changes hands -

it flows from person to person as it circulates around the economy without

being consumed. This is a very important difference between wealth and money

and is discussed in more detail in chapter 14.

Figure 4.6: Wealth transfer diagram showing wealth

transfers in the simple economy

Now here's an interesting question: Should knives and

wheelbarrows be included in the wealth that benefits the members of this simple

society? They are certainly forms of wealth, but they represent a different

kind of wealth from the wealth that benefits the members because they don't in

themselves sustain or improve people's lives, what they do is make the creation

of things that do sustain and improve lives quicker and easier. They are forms

of capital wealth, and as such provide means to ends rather than ends in

themselves. If we only consider the things that sustain and improve lives -

consumer wealth - basic food, luxury food, clothes and jewellery, 180 hours are

spent in producing 12 units (3 people x 4 different types) of this kind of

wealth, which is 1 unit of wealth per 15 hours of work - a fourfold improvement

in productivity - made possible by the application of capital wealth. In the

real world of national economic wealth measurement (indicated by Gross Domestic

Product - GDP - see chapter 26) capital wealth is included, which is fine in

itself because capital wealth production is part of overall wealth output, but

GDP is incorrectly regarded as material wellbeing - which consists largely of consumer

wealth - which it isn't because it fails to exclude the production of capital

wealth.

The real economic value of capital

wealth is not its own exchange value; it is the extent to which it enhances

material wellbeing.

Material wellbeing should not be mistaken for happiness or

contentment, though inadequate material wellbeing certainly causes unhappiness

and discontentment. There is ample evidence that when adequate material wellbeing

is achieved further growth does not lead to greater happiness or contentment. In

fact these qualities depend more on relative rather than absolute levels of

material wellbeing within the population.

This is an important reason why inequality is very bad for the happiness of the

population, regardless of absolute levels of prosperity. It is an even more

important reason why the rich world should devote much more effort to helping -

perhaps ceasing to exploit would be more apt - the developing world, where

absolute levels of material wellbeing for most of the population are completely

inadequate, and a major source of misery. These matters are discussed in more

detail in chapters 73 and 99.

GDP also includes other elements that create even bigger

distortions, so in spite of its importance in economics this figure is very

misleading. I shall argue later that we need a different measure than change in

GDP to indicate change in material wellbeing, and that GDP is itself a

distorted measurement of overall wealth creation - see chapters 26 and 27.

If we include capital goods (i.e. wheelbarrows, knives

aren't included as they are assumed to be quick to produce and keep sharp) as

wealth in our simple economy then we need to count one wheelbarrow as worth two

of any other kind of wealth because it takes 60 hours to keep three people in

wheelbarrows whereas it takes 60 hours to keep three people in two of any of

the other kinds of wealth. So now we have 18 units of wealth produced in 180

hours, or 1 unit in 10 hours, which is a six-fold improvement in productivity. Additionally

while only 30 hours are spent in producing survival needs (basic food), 150

hours are spent in producing surplus wealth.

Here's another interesting question: Who is it that creates

the increased surplus wealth? One view is that it is the knives and

wheelbarrows that create the extra wealth, because without them it couldn't be

created. Fortunately knives and wheelbarrows don't demand a share of the wealth

they help to create so in this simple economy the benefits all go to the

workers since they all work equally hard and share all the benefits, so the

question is merely academic. But what about a modern economy where assembly

line robots build cars and other goods, and the vastly reduced workforce just

look after the robots? Should the owners and remaining workers share all the

benefits of this wealth creation between themselves without considering anyone

else? And if they do then who will buy all the goods? The remaining workers

and owners can't buy them all. And what about a possible future economy where

robots do ALL the work, including robot maintenance? This is a future

that seems a lot less fanciful now than it did not very long ago. How should

the wealth be shared out then? There is no doubt that tools and machines do

indeed create wealth, just as the earth itself and the sun do, and the question

of how machine-created wealth should be shared out is already pressing and will

become ever more so if technology continues to evolve as it has in the past. This

is both a practical and an ethical question, and is taken up later in chapters

78 and 97.

Other questions also arise:

What surplus wealth do machines and their operators create?

It is that wealth over and above that which is needed to allow the human race

to survive, to run and maintain the machines, and to replace them when worn

out.

What proportion of this surplus is created by the human

operators and what by the machines? I don't think there is an appropriate

answer as they work in combination, tools and machines amplifying the

effectiveness of human labour. Each depends on the other and both are needed to

create the wealth. It's like asking which contributes most to life, the heart

or the liver? Since both are essential life can't be apportioned between them,

they both contribute one hundred percent.

This simple economy illustrates the miraculous power that

surplus wealth, specialisation and trade, together with innovation (development

of capital wealth - knives and wheelbarrows), have to make life easier and more

comfortable for everyone. It also illustrates that surplus wealth is in effect

surplus time, and can be taken as additional goods and services, or taken as

additional leisure. In this economy all the surplus wealth has come from

innovation (a two-fold enhancement from knives and a further three-fold

enhancement from wheelbarrows, giving a six-fold enhancement overall if we

include capital goods as wealth, or a four-fold improvement if not). Without

innovation additional surplus wealth can still be produced, but it must come

from working longer hours.

In fact capital wealth and improvements in production

techniques are generally much more effective than this example suggests,

because capital wealth normally lasts a long time and continues to deliver benefits

for many years, and, once they have been implemented, improved production

techniques continue to deliver benefits indefinitely.

Another vital factor in a real economy is that innovation

and technology, once developed, are easy to share, so that the benefits they

bring can be applied by everyone.