Another significant insight emerges from the foregoing

discussion:

The nature of surplus wealth doesn't matter, for the

economy to flourish all that is required is that surplus wealth is traded.

This might seem quite surprising, but once our needs are

catered for how we spend our extra time and what additional things we produce

don't affect our ability to survive and continue the race.

For example, in the simple 3-person economy, instead of

producing clothing Worker A could tell fortunes or paint pictures for the

others, and instead of producing jewellery and gathering luxury food Worker B

could groom the others and sing songs, or keep the homestead tidy and kill

vermin. All those who produce non-essentials can do or produce anything at all

provided that the others are willing to trade their own wealth for it.

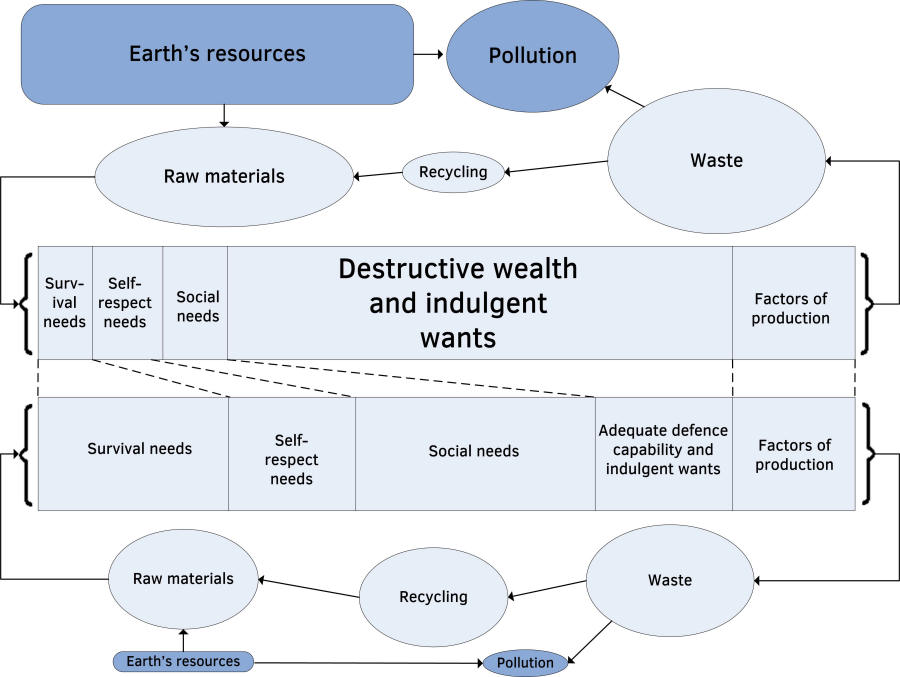

Figure 7.1: The nature of surplus wealth doesn't matter

This feature of an economy is most clearly illustrated by

the production of military equipment and weapons of all kinds. The function of

these things is the exact opposite of providing benefits, it is to cause destruction,

yet the economy that produces them flourishes just as much as production of

things that do benefit humanity.

But, and it's a BIG BUT:

The kind of economy that flourishes depends

critically on the nature of surplus wealth.

So far market freedom has largely been allowed to determine

what is produced - whatever people want (or can be persuaded to want) and are

willing to pay for is what is produced. This leads to the economy that we have

- a selfish individual-centred economy with massive inequality and no barrier

to indulgence for those who can afford it, where individual wants, regardless

of how frivolous or wasteful of resources, are allowed to direct the productive

efforts of the economy. Producers have free reign to persuade us to have

whatever they produce, and everyone can do just as they like. That's the

neoliberal philosophy - everyone should buy exactly what they want to buy and

everyone will be better off as a result. If that had been true then we should

have seen some benefit by now. It is based on Adam Smith's famous 'invisible

hand', but even Adam Smith didn't believe in it as a universal truth like

neoliberals do - see chapter 80.

Free markets are blind, they just follow demand

whatever it is and wherever it comes from.

The more we allow market freedom to decide the direction of

the economy the more indulgent and anti-social it will become. Someone has to

control markets - after all a market is merely a forum for controlled exchange.

At the moment control is exercised by those with the most freedom - the unscrupulous

wealthy - using all their influence to enhance their freedoms and limit the

freedoms of the non-wealthy - see chapter 98. If it continues in that way we

are all in deep trouble.

As Michael Meacher pointed out:

Market profit operates only at the level of the

individual company; it cannot automatically ensure the national interest is

safeguarded across the whole economic spectrum. (Meacher 2013 p178)

Until we recognised the dangers of unsustainability and

climate change we were able to go on happily producing whatever people wanted. The

unscrupulous rich exploited the rest as far as government rules allowed them

to, as they always have done, but now there are new and very present dangers. Allowing

things to continue as they have is no longer an option if we are to survive. Individual

wants won't provide for social needs, only society can do that. Social needs

represent a new imperative that we must respond to.

We must decide as a society what it is that our

economy must deliver - especially social needs - and rearrange our wealth-creating

capacity to deliver them. We have a choice: carry on as we are and die out as

the planet becomes uninhabitable; or change our ways, survive and prosper. Why

is that such a difficult choice?

Neoliberalism makes no distinction between types of consumption

wealth - it believes that all wealth is good - the more stuff we have the

better, regardless of what stuff it is. Therefore current consumption is

largely driven by indulgence - things that satisfy our wants regardless of the

needs of others, whose production methods use up the earth's resources as if

they are infinite, and create pollution without thought for the consequences. Let's

call these indulgent wants. Consumption in the economic sense however encompasses

all forms of consumption, regardless of who does the consuming or how the

things consumed are produced. We are a world society, where consumers in the

developed world can afford to indulge their wants but many in the developing

world can't even meet their survival needs reliably. This represents a

distortion that must not be allowed to continue.

Similarly the prevailing wisdom has it that all jobs are

good for the economy. A business that creates jobs must be a good business. But

just as there is good wealth and bad wealth, there are corresponding good jobs

and bad jobs.

Therefore a lot remains to be said about what we

consume and therefore what wealth we create in order to secure a fair,

stable and sustainable future in the light of massive world poverty, resource

depletion and severe environmental threats. While anyone lacks a survival need,

while we remain at risk from external dangers, and while we are depleting the

earth's resources unsustainably, we need much more humanitarian wealth (directed

at those without survival needs), and sustainable wealth (directed at

countering environmental threats and avoiding unsustainable resource depletion).

It isn't only the populations of poor countries who require humanitarian wealth.

Increasingly in the UK the survival needs of older people are being neglected,

with constant battles for funding between social care and the NHS. These

desperately needed services are deliberately rationed by being starved of

funds, when those funds are directed instead at the rich so that they can

indulge their extravagances - and all because of the neoliberal trickle-down

dogma that declares that everyone prospers when the rich have more. Neglected

old people don't prosper. It should be plain for all to see by now that trickle-down

is a dangerous deception. It is examined and rejected in chapter 20.

We should recognise that over a working lifetime a person

creates a vast amount of surplus wealth, much of it going to society to

exchange for social needs. Part of that surplus buys the person the right to be

cared for at times when they are unable to contribute - when too young, too

old, sick or otherwise incapacitated. More broadly, a working population

creates a vast amount of surplus wealth, part of which buys all those unable to

care for themselves the right to be cared for.

In order to have what is really needed selfish and indulgent

wealth should be cut back considerably but not eliminated completely, after all

people need to have some recreation and enjoyment, they are what make life

worthwhile. It's extravagant indulgence and consumer products manufactured by

unsustainable methods that we can't afford. All this will require very

substantial investment in sustainable production and more efficient recycling

of limited resources, and the wealth that these new processes create will be

more expensive than before. Expensive that is to suppliers and buyers - the

environmental benefits will of course greatly outweigh the costs. Also let's be

clear about humanitarian wealth for poor populations. It is not to be created

and distributed for philanthropic reasons but for reasons of economic good

sense. It brings more people into full production of surplus wealth, thereby

creating more overall wealth - good wealth - for everyone. Currently there are

1.4 billion people living below the absolute poverty line of $1.25 per day, and

contrary to expectations most live in middle-income countries (Chang 2014 p339).

Although many are working they can't fulfil their potential on that kind of

income so their wealth-creating efforts are underused and therefore wasted.

When everyone has everything they need and is fully

productive, resources are no longer being depleted unsustainably, and the

environment is as secure as we can possibly make it for the next several

thousand years, then we can afford to indulge our wants more fully - though as

a world society, not as a rich few and a poor many.

As wealth-creating capacity is re-orientated indulgences

will become less plentiful and therefore more expensive. What will happen is

that efficient indulgences - those that give a lot of pleasure for little

wealth use - will still be taken up at reasonable prices, and these are the

ones enjoyed by most people. Inefficient indulgences will become the most

expensive, and this is exactly what we want. These are the extravagant

indulgences enjoyed by the few. It's the market working as it should.

Another major source of largely dispensable wealth creation

is destructive wealth - military capability and weaponry of all kinds. This

isn't merely wasteful it is intended to be harmful - and the more

devastating the harm the better. As said earlier defence is a regrettable

necessity, but need be no more than sufficient, in conjunction with dependable

allied countries, to counter terrorist threats and to ensure that potential

major aggressors would lose more than they would gain by mounting an attack. Any

excess over this is not for defence, it is either for offence or because it

represents good business. But good business for us - and the UK is a major arms

exporter - is far worse for those on the receiving end or threatened by the

products of that business. They lose far more than we gain, so I can see no

moral case for producing arms for export. Sadly the modern world doesn't

recognise moral cases, it makes money so there is no more to be said. The

same goes for arms for offensive purposes - to mount wars in foreign lands

because we don't like what is happening there. What is happening is often indeed

reprehensible, but using physical force to make changes doesn't generally or

cleanly bring the changes that are desired. Things are always more complex than

they seem as recent experiences in the Middle East testify so effectively. Physical

force is the bluntest of tools. At best it causes seething resentments and

hatred, at worst it triggers unforeseen reactions that can be impossible to

control and are far worse for the populations involved than the original

reprehensible regime.

Whether or not we need growth - more overall wealth creation

- to achieve all that depends on how much of our indulgent and destructive surplus

wealth production we can dispense with in order instead to redeploy it as

sustainable and humanitarian wealth production. There are vast quantities and

ranges of indulgent surplus wealth - ego-boosting rather than purely functional

cars, expensive 'designer' clothes, luxury furniture, lavish entertainment,

'must-have' technical gadgetry, exotic holidays, palatial property,

'fashion-statement' accessories and so on, together with their attendant

advertising and marketing, all of which absorb massive amounts of productive

effort. Beyond all those obvious indulgences there are things that the 'free'

market has given us that we have come to regard as necessities. Things like

private cars, generating enormous amounts of carbon dioxide and other

pollutants, aircraft criss-crossing the skies generating greenhouse gases in massive

quantities, and container ships passing each other on the oceans carrying

unnecessary and often similar goods and burning heavily polluting bunker fuel in the process. We

need to limit usage of these things because the costings are all wrong. People

won't like giving them up, but the question is how much do they really cost?

Pollution costs nothing in currency terms - so we feel free to ignore it - yet

it may end up costing us our very existence! Likewise there are vast quantities

and ranges of destructive wealth, far more than can ever be justified on

defence grounds.

No-one wants to hear all this, we would rather carry on with

our comfortable lives, but that comfort comes with a very heavy and possibly

unpayable price tag. We must face up to the challenge. I don't know what the

relative proportions of wealth-creating capacity are that are devoted to destructive

wealth, lavish indulgences, accepted indulgences, rich country needs, poor

country needs and social needs, but I know that the proportions are completely

at odds with long-term security and sustainability. Is anyone even trying to establish

appropriate proportions? Perhaps they are but their work isn't very evident - progress

should be reported regularly and followed with keen interest.

Modern economists use another assumption to get round all

these difficulties - natural resources are fully substitutable by human

labour and capital (man-made) goods. This convenience makes analysis

easier, but although on occasion there can be such substitutions, normally

human labour and capital goods are used to transform resources into useful

products rather than being able to substitute for them (Daly 2007 pp127-136).

Turning it all around will require very substantial

reorientation of wealth-creating capacity. Whether or not it requires growth

remains to be seen, what we need is a radical shift in the wealth that is

created and the way it is created. If we do need more overall wealth then it is

available from the surplus wealth-creating capacity of people currently unemployed,

underemployed, and employed by wealth extracting companies (see chapter 36) whose

work doesn't help the economy. It is also available from the populations of

poorer countries who at present aren't able to contribute to their full

capacity.

The chance of unfettered free markets and

laissez-faire bringing all this about naturally is as likely as a rudderless

ship setting sail from Liverpool, crossing the Atlantic, and arriving safely in

New York. Neoliberalism has had its chance and has failed completely.

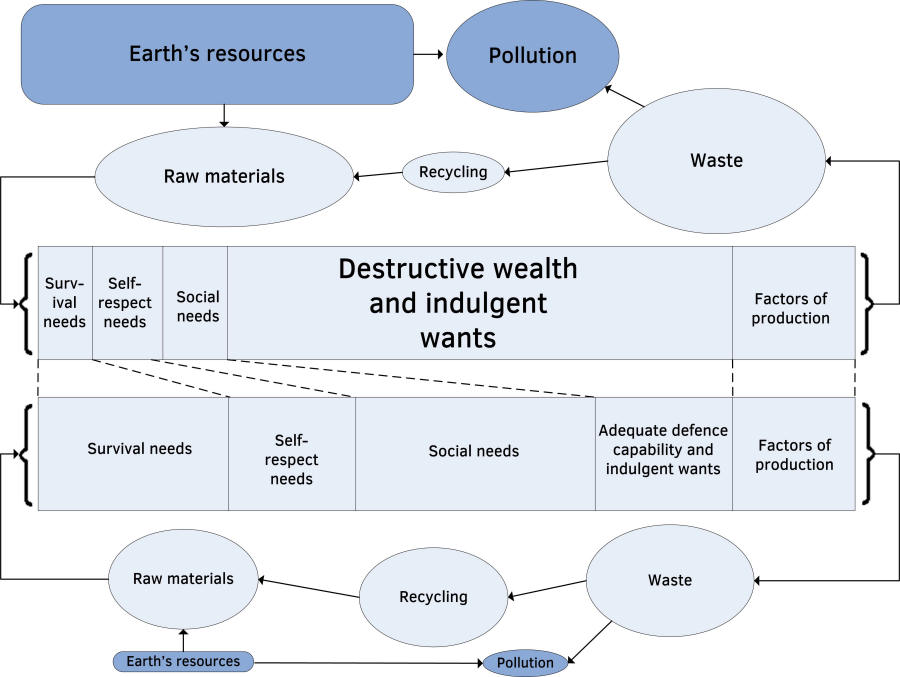

Figure 7.2: Necessary re-orientation of wealth-creating

capacity

In future the emphasis must be on creating sustainable and

humanitarian wealth efficiently, using fewer resources, and recycling more of

those resources. Wealth is no more than human effort directed at achieving a

desirable end, and nothing is more desirable right now than reducing raw

material usage and production of waste. Wealth can do that, as well as devising

the means to restructure existing wealth-creating capacity away from indulgence

towards socially beneficial products. Each country must carry its proper share

in these respects, the lead being taken by rich countries. The work of bringing

poor country populations into full production of good wealth must be shared

fairly between rich countries. However as will be seen in chapter 62 the first

thing that poor counties need is for rich countries to stop exploiting them. The

initial cost to rich countries of helping poor countries will be the loss of

wealth that is unjustly taken from them. Beyond that there will still be a need

for help to bring them up to developed world standards as discussed in chapter 76

section 76.2. Not all countries will be willing to do their part, at least

initially, but that shouldn't prevent others from doing all that they can. All

won't join the communal effort at the same time, but hopefully in time those who

aren't contributing, especially where they still sanction exploitation, will be

pressured by the strength of public opinion into taking action.

Wealth creation and use can be good, bad or

indifferent, but in order to have the things that eliminate both poverty and

environmental threats, and secure the future, we have to create and use sustainable

and humanitarian wealth.

We have considered above the kinds of wealth creation and

consumption that should be cut down or preferably cut out, so what kinds should

take their place? To answer that we must focus on what is needed for a long-term

sustainable future, and for that we must first recognise and face up to the

enormity of the task and mobilise everyone's best efforts in undertaking it. If

we are to succeed then we need everyone's hands on the pump. This demands a

society where all are fully engaged and committed to the common cause. That in

turn requires a society that treats everyone in a fair manner, and is both seen

and understood to do so. We can no longer afford a fragmented and embittered

society of haves, have nots and have nothings. We tried that and this is where

it got us. A society like that can't work co-operatively because it is divided

by hostility.

In particular we must recognise that we all share a single

finite planet, and that it is in all our interests for everyone to share in

both the creation and consumption of the prosperity that is available to us. We

must shake off the wrong-headed view that we only have a fixed-size cake to

share so we must grab as much as we can as fast as we can, and understand

instead that we are the cake makers, and the more we share with others the more

cake those others can make, and the more sustainable wealth in total that can

be created. We must work together, applying everyone's best efforts

collectively and wholeheartedly if impending dangers are to be averted. So far

we have only tinkered with the idea.

What we have is a deeply unfair world that is

unsustainable. If we carry on as we are we won't need to worry about future

generations because there won't be any.

For our long-term viability we must recognise and

face up to the dangers that confront us, and for that we must move from a

grasping selfish culture to one that is sharing, generous and sustainable. IT

CAN BE DONE. All we need is the will to do it.

Initially we need a proper system of accounting that costs

everything properly, including greenhouse gas generation, pollution, depletion

of resources and all other unsustainable activities, as well as including

social costs and benefits. There are such accounting systems, a major one being

Environmental Full Cost Accounting.

This uses what is known as the 'triple bottom line' - People, Planet

and Profit. Each is calculated separately and adjustments made between them to

give a good outcome for each for a given organisation or enterprise.

With such a system in place incentives and disincentives

will emerge and be responded to, setting up a natural migration away from

wasteful or harmful wealth-creating capacity towards sustainable and beneficial

wealth-creating capacity. Transport will be seen to be very expensive, so there

will be a re-orientation towards local production wherever possible. Many

traditional factories and organisations will be seen to be unprofitable and

will change their methods so as to align with the new standards. Governments

will be responsible for enforcing the new standards, with appropriate

transition arrangements to allow time to manage essential changes, and will

carry out major infrastructure investments on their own account. At the same

time the tax system will require major overhaul to bring the necessary wealth

and wealth-creating capacity for all these changes back to society for the

benefit of society. Taxation is discussed in chapter 95.

People able to waste wealth-creating capacity on lavish

indulgence must have that ability curbed, because society can't afford it even

if they can.

To have a flourishing economy based on self-indulgence is

relatively easy. People are eager to have things that benefit them directly so

demand for them is widespread. The market is just as eager to respond by

producing them in abundance, and neoliberal philosophy justifies all this as

right and good. The trouble with this approach is that it not only ignores the

poor and disadvantaged, it is also unsustainable.

Sooner or later we run up against the unwanted effects of

our indulgence - raw materials start to run out; the environment reacts badly

to our polluting it; and diminishing survival needs cause conflicts to increase.

Therefore making the transition to an economy based on what society as a whole

needs will be difficult. Demand won't come naturally from individuals, so

people must be fully informed about the impending dangers and the means to avoid

them. Public support is necessary for government action, support that will only

be forthcoming by making plain the choices that we face and their consequences.

But ultimately it is governments that have to act on behalf of society.

The neoliberal approach of non-interference in the

market has set us on a collision course with nature. Strong and courageous

governments are needed that turn their backs on neoliberalism and steer us away

from self-indulgence towards security and sustainability.

Using a very high proportion of our wealth-creating

capacity and resources to create indulgent wants when there are increasingly

pressing social needs and people dying for want of survival needs is nothing

short of grotesque. It is the modern world's version of fiddling while Rome

burns.

When people fully understand what the problems are, and what

is needed for their solution, then I believe they will respond very positively.

Currently they have the neoliberal doctrine grabbing their attention - do

whatever you can to make money, spend it on whatever you like, and the whole of

society benefits. Therefore our first task is to rid ourselves of that dangerous

dogma and replace it with the truth.

To those who say that these things are too expensive,

or that they would misdirect resources, or that they're completely unrealistic,

I say that we have no choice if we want to stay alive for the long term and

avoid conflict on an unimaginable scale in the medium term as resources run out

and the environment turns against us.

It is almost universally accepted without question that every

country should aspire to as high a level of economic growth as possible. If we

don't create more wealth this year than last then the government is blamed for

having failed in its duty. Why is there such a fixation on growth?

There are several reasons, all of which except the first two

arise because of debt.

·

National league tables are compiled and published, and national

pride is at stake just as football teams' pride is at stake in football league

tables. The government of a country sliding down the table feels shame. It is

falling behind its neighbours and clearly doing something wrong in managing its

economy. The driver is productivity. A country with high productivity stands

high in the world, like a child who joins the highest class in school, or a

sprinter accepted for the Olympics.

·

Wherever anyone finds him or herself in the wealth hierarchy they

are always driven to want more because they are acutely aware that at any time

they may lose what they have. They strive for security, and they believe that

more wealth means more security, though they are chasing a moving target. This

is discussed further in chapter 9. Closely associated with this is the drive

for visible success, which more and more is measured in terms of accumulated

wealth. This is discussed further in chapter 99. Although these are individual

drivers their cumulative effect is to drive for ever more economic growth.

·

There is the national debt, on which interest is payable from

taxation by current and future taxpayers. The only way to avoid taxpayers

suffering a reduction in real

disposable income is for the economy to grow so as to generate enough or more

additional income to cover the tax without affecting disposable income. Taxation

in relation to the national debt is discussed in chapter 100 section 100.5.

·

The need for ordinary businesses to service high levels of debt

(and pay their workforce enough to service its debts) necessitates their having

to compete fiercely in the marketplace, creating a universal and desperate

drive for growth as every business strives to out-compete other businesses.

·

Borrowing from a bank requires payments on fixed dates, with

penalties for late payment. This incentivises individuals and businesses to

generate quick returns in excess of the amount required so as to enjoy peace of

mind, and quick returns are generated by growth.

·

The current system causes house price inflation that is well

above wage inflation. In order to maintain standards of living when housing

costs increase more work must be done and more pay earned or more debts taken

on, both of which generate growth.

·

Loan repayment destroys bank money (see chapter 39), which

without compensation in the form of new debts causes the economy to shrink

(discussed in chapters 15 and 16). The government therefore designs policies to

encourage greater indebtedness to counter these damaging effects, and greater

indebtedness leads to more spending and more growth.

But what's wrong with continuous growth? Nothing if it's

sustainable, but sadly whether or not it's sustainable is hardly ever enquired

into. The prevailing belief is that growth is good - full stop. Therefore the

problem is not with growth in itself, the problem is with growth at any cost. We

live on a finite planet with limited resources and limited capacity to absorb

pollution, and growth, unless it is managed very carefully, threatens to

overwhelm those limitations as indeed it has been doing for many years, and

that stores up very significant trouble for the future.

Continuous unconditional growth is based on an

infinite source of raw materials, an infinite capacity to absorb waste

products, and no impact on the environment, yet we know full well that none of

these is true.

This is a quotation from 'Modernising Money' (Jackson and

Dyson 2012):

The crucial defining factor of a steady-state economy is

that it does not exceed the 'carrying capacity' of its natural environment. Carrying

capacity can be defined as the maximum population that can be sustained

indefinitely by the environment, given that the physical components of the

planet (natural resources, human populations etc.) are constrained by the laws

of physics and the ecological relationships that determine their rates of

renewal. This is problematic as any economy that continually grows (typically

characterised by increased use of physical resources) will eventually exceed

the 'carrying capacity' of its natural environment.

The league table issue has become deeply ingrained in the

consciousness of all governments. As a result the unit of measurement - Gross

Domestic Product - has become distorted over time in order to make it reflect

more growth than is really the case (Fioramonti 2013 pp63-65). This is good in

that less real growth is better for resource depletion and the environment, but

is bad in that performance measurements should be accurate and directed at what

we really want to achieve; not used as a means of fooling ourselves. There is a

lot more said about how growth and economic performance are measured in chapter

26; the point to make here is that growth is not something that we should

aspire to for its own sake unless more overall wealth is needed for a specific

purpose - rebuilding a country after a war or natural disaster, providing for a

growing population, eliminating poverty, or countering environmental threats.

What we should

aspire to is to restructure our existing wealth-creating capacity to serve

humanity's needs better and to do that with as little natural resource

depletion and as little pollution as possible. To do that the league table

needs a new focus - perhaps 'Degree of Sustainable Sufficiency'.

It's worth pointing out a great irony in all this. We

are doing everything in our power to generate growth, telling ourselves that it

will give us a secure future, yet unconditional growth is the very last thing

we need if we are to have any future at all.