To use a scientific analogy wealth is very much like matter.

Matter is anything that occupies space and has weight. Matter has a

natural tendency to accumulate because of gravity, which is a force of

attraction between any two bodies of matter. Hence in space matter accretes

over time to form stars, planets, moons, galaxies and so on. Wealth is the

same, and has its own equivalent of gravity in the feature that things that produce

wealth are themselves forms of wealth. Strictly speaking wealth produced by

assets is transferred to owners as wealth entitlement - money, but the

distinction matters little in this discussion because we are only concerned

with individuals rather than whole economies.

Wealth production can be by creation or transfer. Wealth-creating

assets bring new wealth into being themselves, for example shares in companies

that make new things for sale or provide services or support in making such

things. Wealth transferring assets transfer wealth created by others to the

owners of those assets, for example debts where the debtor creates wealth and

transfers entitlement to it as interest, or property where the tenant creates

wealth and transfers entitlement to it as rent.

When a person has sufficient wealth (or more accurately

entitlement to wealth) they can invest it in assets that produce wealth, and

enjoy the continuing supply of wealth that those assets produce without further

effort, and that wealth can be used in turn to obtain yet more assets. Note

that this form of investment is likely to be purchase of existing assets rather

than new wealth-creating assets, because the vast majority of assets that

produce wealth already exist and are owned by someone else before being bought

by the investor. Owners of assets that deliver wealth or wealth entitlement

without effort are known as rentiers.

Wealth produced by assets gravitates to asset owners,

and because assets are themselves forms of wealth the owners are able to

increase their stock of assets and therefore the rate at which they accumulate

wealth.

The process is further reinforced by the two other wealth

accumulating mechanisms described in the Introduction: wealth extraction and

the fact that more wealth gives more bargaining power.

The natural tendency for wealth to accumulate is disguised

to some extent by the fact that owners of wealth often change over time. Recessions

and especially depressions cause many wealthy people to lose fortunes in terms

of money value as markets collapse, but the wealth they own remains, even

though it is worth less after the collapse. If they sell their assets then

their loss is another's gain, and as the buyer tends to be wealthy the

accumulated wealth generally stays accumulated, albeit owned by someone else. When

markets recover then the value of owned wealth returns to where it was before.

Overall, new wealth migrates towards existing wealth, and

owners of the greatest quantities of existing wealth enjoy the highest rates of

migration. This is demonstrated in great detail by Thomas Piketty (Piketty

2014), who shows that it is the natural outcome of an economic system based on

free markets. The condition that is necessary for it to happen is that the

return on investments of all kinds should be greater than the rate of growth of

national income, which it has been throughout history except in unusual and short-lived

circumstances. Piketty's evidence shows that the normal return on investments

is normally between 4% and 5%, and the normal income growth rate for developed

countries is between 1% and 1.5%, so there is a very significant gap (Piketty

2014 Chapter 10). This is discussed in detail in chapter 97.

The belief of neoliberals that a free market economy delivers

rising prosperity for all is shown by Piketty's work to be badly mistaken. In

fact it does precisely the opposite. The only way to ensure widespread

prosperity is to impose fair market conditions that prevent inordinate wealth

accumulation in the first place (Reich 2016), and to apply deliberate measures

to redistribute existing unfair incomes and wealth. Neoliberalism has not only

failed to apply measures to compensate for the dangerous natural process of

wealth polarisation, it applied significant measures to encourage and speed it

up.

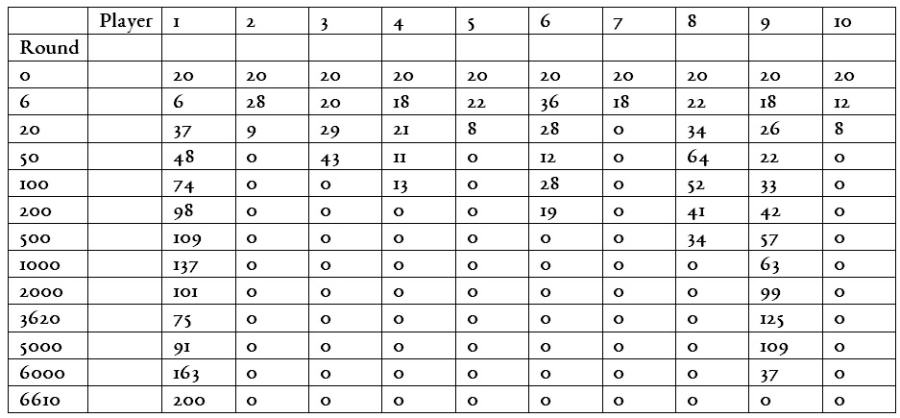

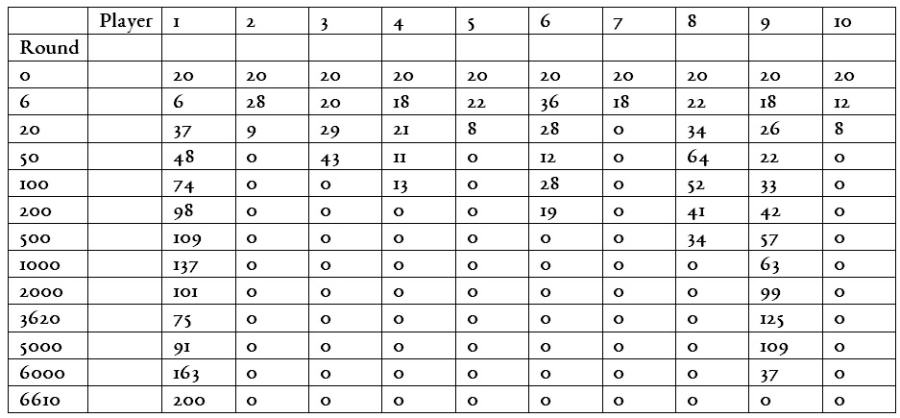

A simple experiment serves to illustrate how inequality can

arise quite naturally, without even the need for any unfairness or exploitation

to speed up the process. Imagine a group of ten players, each starting with a

pot of £20, and gambling with each other on the basis that each pair of players

tosses a coin and the loser pays the winner £1. When a player has lost

everything they drop out. To begin with in each betting round there are 45

pairs.

As players drop out there are fewer betting pairs, until eventually just one

player has £200 and all the rest have nothing. Note that this betting process

is completely fair, all start off equal and the rules favour no-one - there is neither

wealth extraction nor bargaining position benefit. A simple computer program

allows progress to be simulated, and a typical run is illustrated below where

round 0 is the starting position and all numbers represent pounds.

Table 9.1

The reason for growing inequality here is that pure chance

initially allows some players to accumulate more than others, but thereafter a

player who has more must suffer a longer losing streak to fall out of the game

than a player who has less, so the odds favour players with more as the above

table indicates. Chance also plays a significant part, as some players can do

well in spite of the odds being against them. Take round 6: at that stage

player 1 has only £6, less than every other player, so no-one would give much

for her chances, yet by round 20 she has the most and goes on to win everything.

Take round 50: player 8 has the most at £64 and must be feeling good, yet by

round 1000 she is out. After round 1000 there are only two players left, with

player 1 well ahead and happy, but by round 3620 player 9 is ahead. In fact

from round 1000 it takes another 5000 rounds for one of them to gain any real

headway, and even then it takes another 610 rounds to defeat the losing player.

In betting players have the option of walking away, but the

real economy allows no such option.

This experiment shows that there is no reason to assume that

a particular series of interactions will tend towards equality unless the

mechanisms at work are very well understood and known to produce that outcome. The

mechanisms at work in the real economy are well enough understood to know that inequality

- and growing inequality - is inevitable.

The experiment is also sufficiently like real life to reveal

something else, and that is that everyone has good reason to feel

insecure. The multimillionaire envied by all around is very nervous of losing

her millions, which is entirely possible but little acknowledged by poorer

people. Take someone with £1 billion. To everyone else she is bulletproof, but

within her own head there are many ways in which she can lose heavily, and for

her losing £800 million would be a disaster of the first order. People with a

lot of money who lose heavily don't feel good just because by ordinary

standards they have a lot left; they feel awful because of what they have lost.

Also everyone lives within their own social circle, and a wealthy person who

loses more heavily than others in the circle feels bad not only because of the

loss itself but because of loss of position within the group.

Therefore we should recognise that wherever we find

ourselves in the wealth hierarchy we are always driven to want more because

only by having more can we feel secure, though we're chasing a moving target. If

I have £1 million I feel sure that with £2 million I would feel really secure,

but with £2 million I need £4 million, and so on indefinitely. This is all

psychological but very real in its effects on people's behaviour, and a major

factor in the constant drive for more. To the rest of us it looks like pure

greed, but there's a lot more to it than that. Chapter 99 discusses another

major driver for wealth accumulation - visible success.

Although wealth accumulates to the already wealthy,

it doesn't necessarily accumulate for any individual wealthy person, and that

is a major source of insecurity regardless of where a person sits in the wealth

hierarchy.

A social security system that provides a real safety net for

anyone who finds him or herself in straitened circumstances is a benefit to everyone,

and capping the wealth of the wealthy in order to provide it is a benefit to them,

though they deny it and fight against it. As is already known it isn't absolute

wealth or absolute income that matters to people, it is relative wealth and

relative income, relative that is to others in a person's social circle. Therefore the

rich can still have what they want without having as much wealth, and all of us

can enjoy a real and effective welfare state. Chapter 97 discusses the work of

Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett (Wilkinson & Pickett 2009) which shows

very clearly that more equal societies fare better for everyone on every front.

Figure 97.4 in chapter 97, reproduced from their book, shows how health and

social problems become progressively worse as populations become more unequal. These

matters are discussed further in chapters 97, 99 and 100.