We need to determine who buys what in order to find out

whose behaviour is most helpful to the economy and whose is least helpful, and

from that decide who should be encouraged in their normal habits and who should

be discouraged.

What do people spend their money on? It depends of course

on how much money and wealth people already have. People with almost none can

only buy things that are vital to life itself, and there are many who lack even

the means to do that. The more wealth and money they have the things people buy

move up the scale from survival needs to self-respect needs to wants and

luxuries - see chapter 6. When people have enough to satisfy most of their

desires they generally become concerned about maintaining the value of the

wealth they have, and this opens up a vast range of potential investments -

things to buy that hold out the hope of at least maintaining and possibly

increasing their value over time.

Traditional economic wisdom has it that investment is good

for the economy. The argument is that the more rich people have the more they

invest and the more that creates jobs and benefits everyone by increased

production in the future. If poor people have more money they don't invest it,

they merely spend it on additional consumption, which does nothing for the

future and once spent the extra money is gone. Investment is good for the

economy, consumption is bad. This argument is superficially appealing but it once

again confuses wealth with money. Spending on consumption means spending on new

wealth, and as shown in chapter 14 it is exactly this form of spending that

maintains the economy. When spent on new wealth money pays its production costs

and an element of profit, so it at least enables another similar product to be

produced. If demand is high enough the producer will use the profit to expand

production, so in these circumstances consumption spending does increase

investment. As will be shown in section 20.4 investing money more often than

not does nothing for the economy. Traditional economic wisdom, although it

sounds reasonable, has it precisely backwards!

In the traditional view inequality is a side effect of

policies that make the overall economy bigger, and everyone, including poorer

people, are better off than they would be with a more equitable distribution of

wealth. This is the famous 'trickle-down' belief that is used to justify ever-increasing

income and investment returns for the already well paid, and those associated

economic policies that promote it. This policy is about further enriching the

already rich by giving them the lion's share of created wealth, so that

although they become vastly richer than the majority in absolute terms - so the

theory goes - the majority have more than they would have if the rich took a

smaller share. As usually stated the philosophy promises ordinary people a

small slice of a very big pie, which is bigger than a big slice of a very small

pie. I hope and trust that faith in this belief is wearing very thin by now,

after nearly forty years of such policies with massively increasing wealth and

income gaps, little or no benefit to ordinary people to show for it, all

economic growth captured by the already wealthy, and a massive worldwide crash

that all but finished the modern economy altogether. Of course those who are

truly faithful to this theory still believe in it, asserting that its apparent

failure was due to the policies of the last thirty-odd years not going far

enough - if the medicine didn't work then the dose can't have been big

enough.

John Quiggin expresses the accepted view very succinctly:

...according to the trickle-down story, that which is

given to the rich will always come back to the rest of us, while that which is

given to the poor is gone forever. (Quiggin 2010 p150)

The basis of the trickle-down theory is that everyone who is

rich uses all income greater than that needed for their own consumption for

investment, and investment means setting up new businesses or expanding

existing businesses, thereby creating more wealth, more jobs and increased

prosperity all round. After all you never get a job from a poor person -

right? It sounds plausible, but it is easily shown to be false. The pie is

the total wealth (national income) created in an economy in a given time

period, and no matter who does what it can only get bigger until all spare

capacity has been used up,

thereafter it stays the same. At that point a bigger share of wealth

entitlement for the rich must be balanced by a smaller share for everyone else,

so even if it works at all workers can only be better off while spare capacity

is falling, which can only be a transitory phase, afterwards they will become

progressively worse off. The idea that the rich can be given a bigger share of a

static national income continuously and as a result the non-rich also get a

bigger share of a static national income continuously makes no sense at all. In

fact we'll see that in the real world spare capacity doesn't fall at all, so at

no stage are workers better off.

Let's give the rich more money and assume that they spend

all the excess over their own requirements on new and expanding businesses -

i.e. on creating new jobs - and see what happens. Let's also assume - to keep things

simple - that the money supply remains in step with overall production at all

times. More and expanded businesses means more production, more employees

earning wages means more demand - all good so far - but then we reach full

employment and no more spare capacity. At that stage the rich are still getting

more money than they need for themselves, so they continue to set up and expand

businesses. But now there aren't any unemployed workers waiting to be hired,

workers have to be attracted from existing employment, so higher wages must be

offered. Workers transfer from lower wage jobs leaving them short-staffed, so

they too must offer higher wages, but no additional wealth is being created

because there is no more spare capacity to create it. In order to pay for the

higher wages the business owners are forced to reduce their own profits. Workers have

more money, so they can pay higher prices for things that workers buy, but

business owners have less money, so they aren't able to pay the original prices

for the things that business owners buy (capital goods and premises for new and

expanded businesses), and therefore they buy fewer of them. Remember that in

this theory the rich spend all their excess income on production, so as their profits

diminish the rate at which they can set up and expand businesses also

diminishes, until they have no excess income. At that stage there is nothing

driving further change, but the proportion of national income going to workers

has risen because of the wage rises, and the proportion going to the rich has fallen

because of the falling profits. The transfer from the rich to workers began

when full employment was reached (before that both the rich and workers became

better off as spare capacity was absorbed), and stopped when the rich had no

excess income to invest.

Is this what has happened over the last thirty odd years

that trickle-down has been paraded before us as the utopian dream? Clearly not.

As Nick Hanauer

said:

...if it was true that lower taxes for the rich and more

wealth for the wealthy led to job creation, today we would be drowning in jobs!

We would soon have seen full employment, which would have

been preserved thereafter as workers became ever better off and the rich became

ever worse off. Ha-Joon Chang also recognised the fallacy:

Once you realize that trickle-down economics does not

work, you will see the excessive tax cuts for the rich as what they are - a

simple upward redistribution of income, rather than a way to make all of us

richer, as we were told. (Chang 2011 p xvi)

It's true that you seldom (not never) get a job from a poor

person, but you don't get a job from most rich people either. Jobs in the

private sector are only offered if they make more money for business owners

than the cost of the employees. Trickle-down would have us believe that

rich people offer jobs even when it makes them less money! Do you

think the rich are that daft? No, neither do I. This point is key:

A person is only employed as long as the employer

profits from their labour.

The glaring fallacy in the theory is that the rich don't use

all their excess income to set up and expand businesses, they certainly invest

their excess money, but there are many more investment opportunities than

setting up and expanding businesses. In fact most rich people don't set up or

expand businesses at all. New businesses are set up by entrepreneurs, many of

whom have good ideas but no money of their own, so they have to borrow it - these

poor people do offer jobs. Furthermore, the motivation for expanding

existing businesses does not come from the rich having excess money, but from business

owners responding to increasing demand - real or anticipated - when the money

needed often has to be borrowed, especially in the case of small businesses. The

rich much prefer 'hoover-up' to trickle-down. The way they achieve it is by

taking advantage of the process whereby wealth attracts wealth. The more wealth

a person has the more they are able to profit from the work of others, by

employing them directly if they make more money than their own wages, by buying

property and renting it out, by lending money at interest, or by investing in

one of thousands of existing businesses that profit from the work of others. The

way it works is discussed in detail in chapter 97.

In any case even business owners and managers don't want to

create more jobs. They will if demand requires it, but only as a last resort. Almost

any other means of production is preferable to employment, the ideal for them

is fully automated production - roll on the robots! Business owners and

managers much prefer to shed staff than employ staff, and if they can find a

machine to replace workers then they grab it with both hands. This certainly isn't

meant as a criticism, it's just the way things are, and there are very good

reasons for it which are explored in more detail in chapter 100 section 100.2.

This is the employment conflict - people want jobs

but potential employers don't want to provide them.

In fact it's only a conflict if the focus is on jobs, when

the focus should be on what those jobs deliver - tradable wealth for the

employer and security for the employee. A job is merely a means to two distinct

ends after all; the ends - different for employer and employee - are what

really matter. If wealth-creating capacity is re-orientated as discussed in

chapter 7, and society is given a proper role as will be discussed in chapters

30 and 100, then the conflict disappears.

Let's revisit John Quiggin's statement above. "...according

to the trickle-down story, that which is given to the rich will always come

back to the rest of us, while that which is given to the poor is gone

forever." Why does this sound so plausible if it isn't true? It's

another example of confusing money with wealth. If money is given to the poor

it is spent on basic consumption, and the things they consume are certainly

gone forever. The focus is on the wealth they buy, and that wealth is gone

forever by being consumed. But almost all wealth is for consumption whoever

buys it, that's ultimately what all wealth is for, so it makes no sense

to blame the poor for consuming wealth when that's what the whole of humanity

and every other living thing on the planet does. What about the rich?

"...that which is given to the rich will always come back to the rest of

us...". This acknowledges that the rich don't use all their income in

buying wealth for consumption, so not all the wealth they buy is gone forever -

not immediately anyway. It would be fine if all the wealth they bought that

wasn't for consumption was for creating new wealth, that would lead to more

prosperity for workers as argued above, but it would also lead to less

prosperity for the rich and we can't blame them for not being too keen on that.

Instead of focusing on wealth we should focus on production,

and the money - that wonderful lubricant - that brings it about. Money doesn't

go forever by spending it on new wealth whoever spends it, it merely changes

hands, and in doing so it enables the next pair of hands to spend it as well,

and the next pair and the next. Recall the story in chapter 14 about the £10

note lost in a pub, it enabled far in excess of its own face value in wealth to

be produced, and it did that because everyone spent it in its entirety, no-one

saved or invested any part of it, yet it induced everyone to do work - to

produce new wealth - and that's exactly what giving money to the poor does. It

is spent in its entirety and that helps the economy and all of us.

What's happening is much clearer when we take a very simple

look at the difference between workers and investors:

Workers give more than they take, otherwise they're

out of a job. Investors take more than they give, otherwise they ditch the

investment.

That's not to say we don't need investors because we do. But

let's stop adding to the favours given to investors because that only increases

the ratio of what they take to what they give, and where does the extra come

from? From workers, who suffer an increasing ratio of what they give to what

they take. That's the effect of the trickle-down fantasy in a nutshell.

But what about the bigger pie? Well the pie (total wealth)

only gets bigger as more people create wealth, and that would happen if

trickle-down worked as promised and rich people continued to create jobs, at

least up to full employment. But full employment increases security for working

people, and security brings confidence in wages, so a fully employed population

tends to be well paid because anyone in a poorly paid job can more easily find

another job where the pay is better. Much better (for the rich) is to ensure

that workers are insecure, with a high rate of unemployment, so that those in

poorly paid jobs stay put because they can't easily find a better-paid job. Worker

insecurity keeps labour costs down and makes more profit for business owners

(Hahnel 2014 p167). A high rate of unemployment keeps the pie small. What the

myth of trickle-down achieves is the rich having a bigger share of a small pie

rather than a smaller share of a big pie. And the workers? They get a very

small share of a small pie rather than a bigger share of a big pie - that's

the wonder of trickle-down!

But, you might point out, we have had full, or almost full

employment for much of the neoliberal era. We have, Great Recession excepted, but

only because 'full employment' has been cleverly redefined as the 'non-accelerating

inflation rate of unemployment' - NAIRU.

This says that as employment increases so does inflation, and at a high level

of employment inflation starts to accelerate out of control - just look what

happened in the 1970s! So there is a level of unemployment - about 5% -

that prevents inflation from accelerating, and that is the level that is referred

to as full employment. This is indefensible. 5% of the workforce - one in

twenty people able and willing to work but forced to remain idle - is a tragedy.

But it's worse even than that. There are many people classed as employed who

are working far fewer hours than they would wish to, these are the

underemployed. Worse again is that many have given up on ever being able to

find work, and many more suffer from stress and other long-term conditions that

render them unable to work. Much worse still is that the 5% figure hides the

distribution of unemployment, which is weighted heavily towards the young - the

group that should be most strongly encouraged to develop the practical working

skills that can only come from real work for the security of future

generations.

In truth inflation can be fully controlled at any level of

employment, but only if we rid ourselves of the unfettered market ideology and

ensure that the state, on behalf of society as a whole, takes much firmer

control of the money supply. The way forward in this respect is discussed in chapter

55 and chapter 100 section 100.2. Tolerating an acknowledged unemployment level

of 5% together with all the underemployment and badly-allocated employment is

one of the most culpable forms of waste - see chapter 22. The good work these

people could do and the benefit that society could enjoy as a result of the

bigger pie they could make is irrevocably lost.

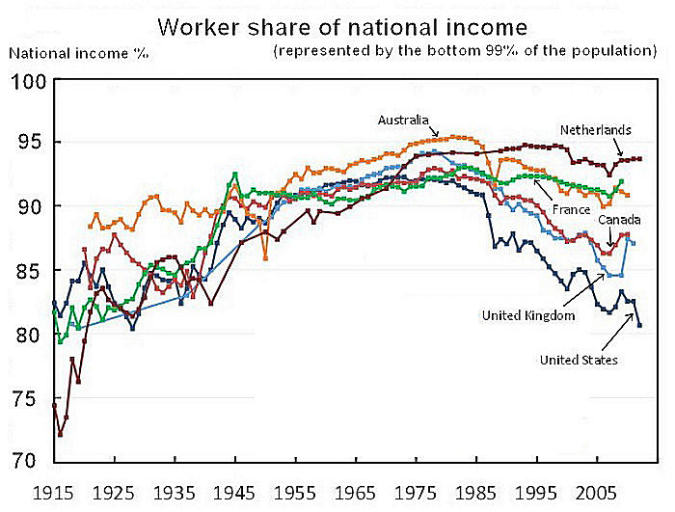

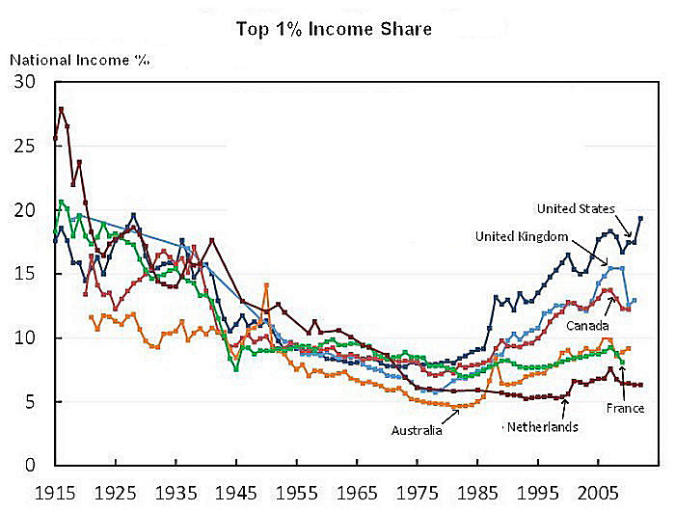

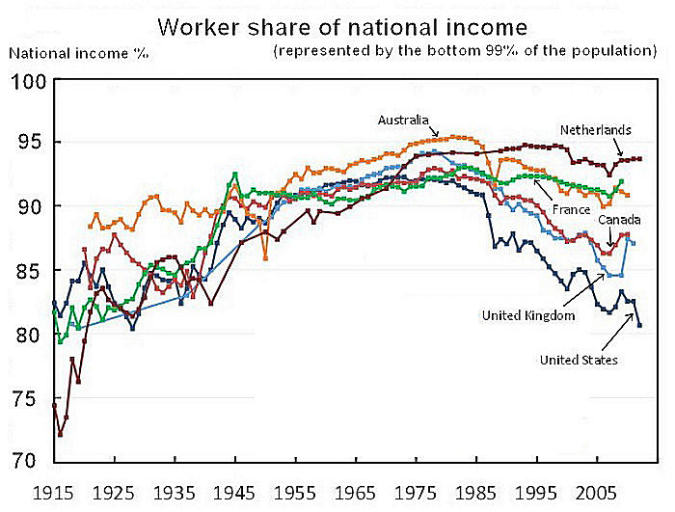

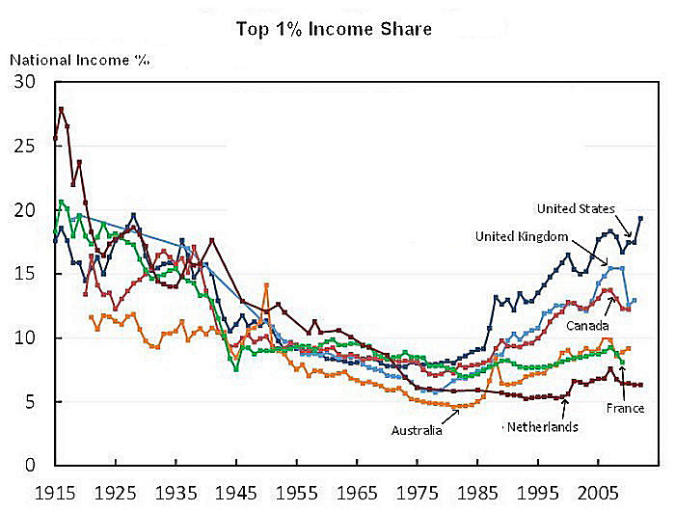

When Keynes' ideas were adopted after the Second World War

employment rose very significantly (in spite of his ideas being misunderstood),

and as a result the share of output consumed by workers also rose. In fact the

worker share had been rising since the end of the First World War but in a

volatile manner, whereas after the Second World War the progression was much

smoother. This is shown clearly in Figures 20.1 and 20.2, which also show it

ending very sharply after 1980 when neoliberalism took over. Leading the

inequality race is the US, followed by the UK and Canada, and then Australia. The

Netherlands and France show a much flatter progression with little if any

decline.

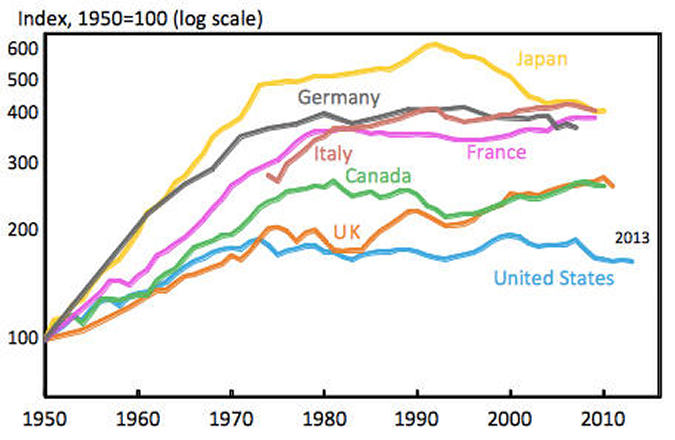

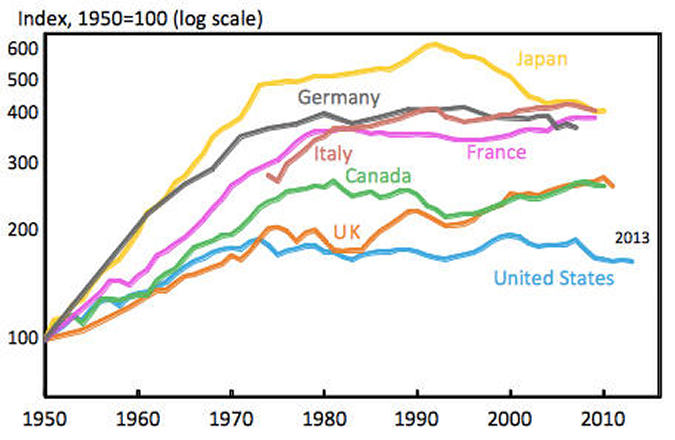

Although the share of national income has diminished for the

bottom 99% in most developed countries, it might still have risen in absolute

terms if national income had grown more than enough to offset the decline in

share. This is the trickle-down theory, which is seen not to work when we look

at a chart of real income. Figure 20.3 is for the bottom 90% rather than 99%,

but the bulk of workers are still represented in this group.

Figure 20.1: Derived from the next chart for the working

population (represented by the bottom 99%)

Figure 20.2: Source - World Top Incomes Database, Council

of Economic Advisers (CEA) within the Executive Office of the President

of the United States. Retrieved from http://www.policy-network.net/pno_detail.aspx?ID=4691&title=Global+lessons+on+inclusive+growth

Figure 20.3: Growth in real average income for the bottom

90%. Source - World Top Incomes Database, Saez (2015), Council of Economic

Advisers calculations. Retrieved from http://voxeu.org/article/brief-history-middle-class-economics

We see that there was substantial real growth in worker

income up to about 1980, after which it started to flatten, showing that the

real income for workers has either not risen at all since then or only risen

slightly. When considered in conjunction with the share of national income

going to the top and bottom we see that practically all the benefit has gone to

those at the top.

There is no wealth trickling down, but plenty

hoovering up!

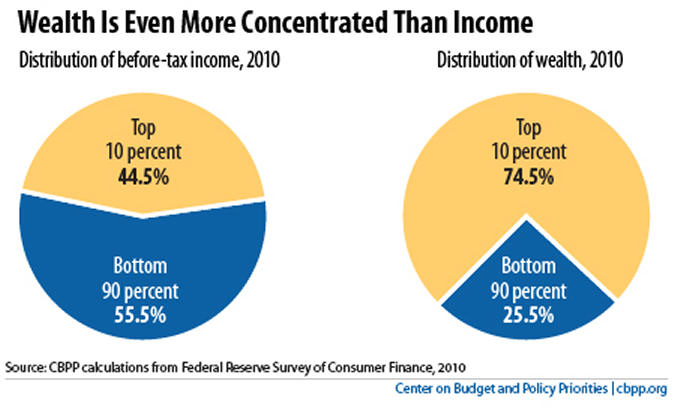

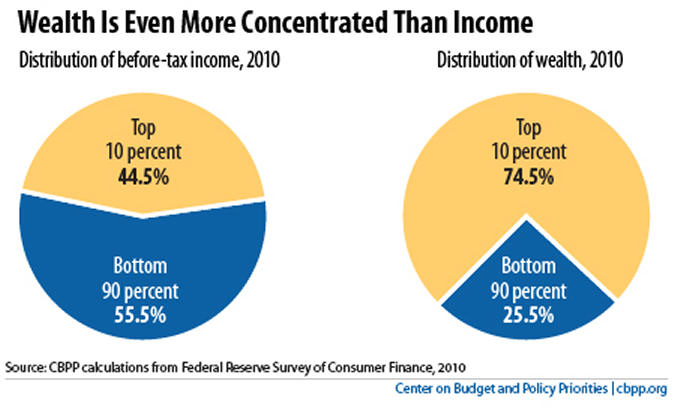

Those charts were for income, figure 20.4 gives the picture

for wealth which is even more unequal.

Figure 20.4: US Wealth Distribution 2010. Source - Center

on Budget and Policy Priorities' calculations from Federal Reserve Survey of

Consumer Finance, 2010. Retrieved from https://fabiusmaximus.com/2013/12/16/income-wealth-political-inequality-60246/

The reason is the by now familiar 'wealth attracts wealth'

phenomenon. This ensures that a significant and increasing proportion of the

income of the non-wealthy reverts to the wealthy through debt interest,

property rents, product profits, wealth extraction and stronger bargaining

positions. These effects should be taken into account in looking at the earlier

income distributions, in that even though the non-wealthy suffer declining

income shares the charts still paint a picture that is too rosy for them,

because the more wealth the wealthy own the more that poorer people have to

borrow it back from them in order to live, so an increasing proportion of their

income goes straight back to the wealthy in rents and interest etc. rather than

being available for spending by them on things that improve their wellbeing.

Let's return to investment, to see what the wealthy spend

their money on. In fact there are many forms of investment, and only some of

them - those that promote the creation of new wealth - add to the stock of

wealth in the economy. I shall refer to these as wealth-creating investments.

These are investments whose objective is to add value - to create additional

wealth - for example by making new things or by supplying services. Investment used

to set up or expand a business that makes and sells useful products, or

provides services, is a wealth-creating investment. Most investments are not of

this kind, they are existing-asset investments, where existing assets

such as property, shares, bonds and other forms of tradable debt, derivatives and other forms

of contract, funds and trusts, are traded between investors. New debts are also

included in the existing-asset category because they represent the purchase by

the lender of an obligation on the part of the borrower to repay in due course more

money than was lent. Money for repayment may be obtained by new wealth creation

by the borrower, but if it is then the wealth creation isn't brought about by

the debt. Note that existing assets may or may not be wealth. Property is

wealth and shares are contracts that give entitlement to wealth, but debts and

many derivatives are based on money. Most bank loans are for things other than

wealth creation, and derivatives and other contracts often represent no more

than bets on some eventuality. Such trading does nothing but change the

ownership of things that already exist, so it does nothing for the economy -

though it often does a great deal for the investors.

Investment takes two forms: wealth-creating

investments, which are few but increase wealth in the economy, and existing-asset

investments, which are plentiful but do nothing for the economy.

If an existing asset increases in value then the

increase is not new wealth, though it feels like it to the owner. All that has

happened is that a buyer is willing to pay more for it than the original buyer

paid.

It should be noted that wealth-creating investments are good

for the economy in the chapter 7 sense only if the wealth they create is

beneficial and the production methods they employ are sustainable. In further

discussion of wealth-creating investments these conditions are taken to apply

so they are regarded as good for the economy. Where they don't apply the

corresponding investments are not good for a fair and sustainable economy.

It is unfortunate

that there is only one word 'investment' for both wealth-creating and existing-asset

investments, because they are very different in their effects, and having a

single word gives the impression that all investment is the same.

The situation isn't helped by economists defining

'investment' differently to its use in plain English. Their definition is the

value - expressed in money terms - of new and replacement capital goods and

increased product inventories. Therefore when economists talk about

'investment' they are usually talking about wealth-creating investment, which

is good

provided that the wealth they create is beneficial, whereas when non-economists

hear them they aren't aware of their limited definition and think they are

being told that all investment is good.

Wealth-creating investment is doubly beneficial to

the economy because not only does it aim to improve wealth creation in the

future, it also represents spending in the present on new wealth in the form of

capital equipment or labour, and spending is the life-blood of a well-functioning

economy.

Perhaps surprisingly it is not easy to put money into wealth-creating

investments. Entrepreneurs are the people who do it regularly but there are

relatively few entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs seek out wealth-creating

opportunities and invest in them, risking their own or other people's money in

the hope of high returns from the products and services of new or expanded

businesses. Those products and services represent new or improved forms of

wealth, and to the extent that they are successful - that is the risk the

entrepreneurs and the new businesses take - the economy benefits from them. Lending

to entrepreneurs is a way of investing in new wealth creation, but it is very

risky so investors tend to use only a very small proportion of their

investments for this purpose. There are companies that specialise in

entrepreneurial activities, but buying shares in such companies is not the same

as investing in wealth creation, it is merely a change of ownership of existing

shares. Buying shares in a new business in an initial public offering (IPO) can

be a wealth-creating investment but only if new money is being raised to expand

the business. Often such a purchase is just a change of ownership from private

to public, and in that case again it is just a change of ownership of existing

assets.

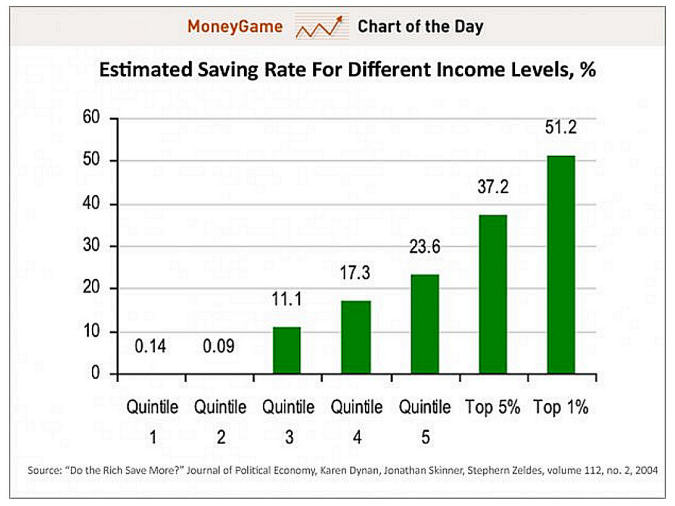

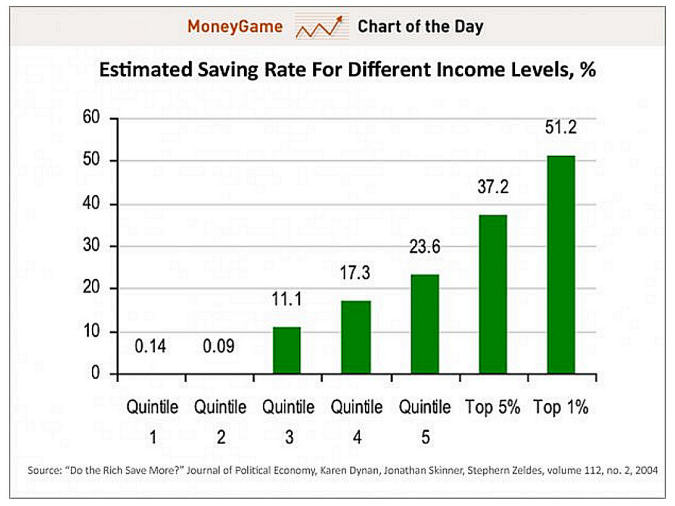

Figure 20.5 shows the increased saving (non-spending) as

people become more wealthy.

Figure 20.5: The extent to which people save (invest) more

as they become richer. Reproduced from Business Insider, March 1 2013, 'Rich

People Really Love To Save Their Money' by Sam Ro, taken from

data published in the Journal of Political Economy Vol 112, No 2, 2004 (table 3

column 2), 'Do the Rich Save More?' by Karen Dynan, Jonathan Skinner and

Stephen Zeldes

It should also be recognised that when a business seeks to

expand or a new venture to start up those running or wanting to run that

business will seek the funding they need from wherever it is to be had - often

from retained profits in the case of large existing businesses (Kay 2015 p164).

But here the demand for funds from the wealth-creating activity comes first and

the provision of funds second, the driver is the wealth-creating activity. The

conventional view about wealthy investors is that their ability and willingness

to invest comes first and as a result wealth-creating activities appear from

somewhere and absorb that investment, so the driver is the investor. I hope the

above argument dispels that view.

The desire for wealth-creating investment comes from

people who want to start up or expand businesses, not by investors. Investors

are free to choose between all forms of investment, their only concern is a

high return.

A word should be added about the retail industry, where

existing products are bought, generally from wholesalers or producers, and then

resold to the public. This might be viewed as an exercise in existing-asset

investment on the part of retailers but th