Here the relationships between the various elements of an

economy are developed in order to reach a clearer understanding of the things

we are particularly interested in like material wellbeing and growth or

decline, and the things that influence them. However the analysis is only

relevant for the economy as a whole, it gives no indication of the distribution

of wealth and wealth entitlement.

The chapter includes a lot of maths, which is necessary to

illustrate the derivation of standard economic equations. These equations are

used to provide a very simplified way of picturing what in reality is an

immensely complex web of interactions. Understanding it is not necessary for

subsequent discussion so if maths isn't for you then just skip it.

Economic growth and material wellbeing are discussed in

terms of what it is that delivers them. It is not intended to imply that they

are desirable ends in themselves unless they are delivered sustainably - i.e.

with insignificant impact on natural resources and the environment - see

chapter 7.

Each country prepares National Income Accounts, which

set out its economic activity within a certain timeframe. It lists all sources

of domestic income and records how that income is allocated. It allows the

country's gross domestic product (GDP) to be determined. The UK's accounts are

recorded by the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

First it is necessary to define the terms used and to be consistent

and as precise as possible whilst recognising that complete precision is not

possible. Fioramonti discusses the problem in his book (Fioramonti 2013 Chapter

2). Definitions in economic texts tend to differ and are often not set out

explicitly, so they are often difficult to understand and it's hard to gauge

their impact on overall growth and material wellbeing. It is hoped that the

definitions used here allow growth and material wellbeing to be understood in

terms of their component parts. Some of the terms have been mentioned before. I

have used the general term 'wealth' where products may be goods or services:

Capital wealth is that which facilitates the

production of finished wealth (see below) without becoming part of that wealth.

Examples include tools and machines, skills, techniques, organisation, research

and development, education and training. It encompasses the knives and

wheelbarrows used in the simple economy - see chapter 4. It also includes new

capital wealth used to replace that which is no longer working. New replacement

wealth is needed to compensate for depreciation, but depreciation is excluded

from GDP, in fact that's what 'gross' means. If depreciation is subtracted from

Gross Domestic Product then we have Net Domestic Product.

Consumer wealth is that which directly sustains or

improves people's lives.

Finished wealth consists of things that are directly

usable and ready for sale as opposed to things that are still in the process of

being made or things that have been sold. It encompasses unsold capital and

consumer wealth and also unsold outputs, including raw materials used as inputs

in other manufacturing processes.

Intermediate wealth includes everything that is

awaiting assembly or in course of being assembled into finished wealth, and administrative

services necessary to produce finished wealth such as production management and

stock control. Intermediate wealth eventually becomes finished wealth. Examples

include raw materials bought from suppliers, unassembled or partly assembled

components, and associated administrative services. It excludes things that are

needed for production but have not yet been obtained by the producer. For

example boxes of screws awaiting sale from a screw manufacturer represent

finished goods, but when bought by a furniture manufacturer they become

intermediate goods. It also excludes things needed to maintain wealth-creating

capacity - these are overheads.

Overheads consist of everything needed to maintain

the wealth-creating capacity (as opposed to production itself) of an economy. Overheads

represent a type of investment wealth, but a type that maintains wealth-creating

capacity as it is rather than increasing it. This is a term seldom used in

analyses of economic growth and GDP but Fioramonti draws attention to its

importance in his book (Fioramonti 2013 p60). It includes all consumables required

for operating capital equipment and administrative services directed at

maintaining wealth-creating capacity such as maintenance scheduling. It also

includes government expenditures such as national infrastructure repair works,

policing, security services, environmental protection, healthcare and many more,

since all these things maintain the wealth-creating capacity of the economy in

terms of healthy people and well-functioning infrastructure. Just as human

beings and all living things need to consume wealth in order to stay alive and

functioning, capital wealth also needs to consume wealth in order to remain

functioning. This type of consumption has a different nature to human

consumption because in itself it doesn't sustain or improve lives, so we give

it a different name to avoid any confusion. In the simple economy in chapter 4

wheelbarrow maintenance and knife sharpening are overheads, though the term

wasn't used during that discussion to avoid unnecessary complication.

Investment wealth consists of capital, intermediate

and finished wealth, and overheads.

Inventories consist of intermediate goods and stocks

of finished goods (services can't be stockpiled so inventories just consist of

goods).

Of particular concern are changes from one accounting period

to the next, so time is taken into account in terms of production, consumption

and so on within a particular accounting period, normally a quarter or a year. The

basic economic elements are consumption, investment, saving, government spending,

taxation, exports and imports, all within the period of interest. GDP

represents overall (economists prefer 'aggregate' when referring to the whole

economy) economic output in the period, which is the production of all new

wealth, so it includes the value of all consumer and capital wealth that is

sold in the period and also changes in inventories from the beginning to the

end of the period. We are only interested in changes in this wealth because the

period starts with a substantial amount already in place, so that must be

subtracted from the amount that is in place at the end of the period, giving

the change which can be positive or negative. Transfers of existing wealth and transfers

of money other than for new wealth are ignored because in themselves they don't

affect aggregate economic output. In fact transfers for any purpose other than

for the sale of new wealth are ignored, because our only interest is in

aggregate economic output - i.e. new wealth. This can be confusing. Borrowing

is a money transfer, but what about interest? That might be considered payment

for the service of making money available.

In the case of business borrowing it is assumed to be for investment purposes

so it is counted and lumped in with private investment. In the case of consumer

borrowing it is counted and lumped in with private consumption. In the case of

government borrowing however interest is regarded as a money transfer, being a

transfer from society as borrower back to society as lender - aggregate output

not being affected. The essential point is to ensure that all new wealth

creation and consumption is counted somewhere, but only counted once.

Transfers of money without anything in return are known as transfer

payments, examples being benefits, pensions and subsidies, but I think it

is clearer if we extend the definition of this term to include all money

transfers for other than the sale of new wealth, and that is the sense in which

it will be used in this analysis.

First we derive the equation for GDP in terms of spending on

new wealth - this is known as the expenditure equation, also known as

the output equation and as the national income identity. We need

only consider consumer and investment wealth, because together they account for

all wealth changes over the period. Note that a change in intermediate wealth

over a period will be reflected as a corresponding change in investment wealth.

Consumer wealth - (here denoted by 'C') can either be

consumed domestically or consumed abroad, and can either be produced

domestically or produced abroad. The same applies for investments (here denoted

by 'I'). We are only interested in domestic aspects for our own economy, so

things that are both produced abroad and consumed or invested abroad don't

concern us.

Wealth (for consumption or investment) produced domestically

will be denoted by 'pd', and produced abroad by 'pa'.

Wealth consumed domestically will be denoted by 'cd' and

consumed abroad by 'ca', and wealth invested domestically will be denoted by

'id' and invested abroad by 'ia'.

Gross domestic product (wealth expressed in money terms -

also known as gross domestic output) consists of all wealth produced

domestically, and is denoted by 'Y'.

Therefore:

Y = Cpd + Ipd = Cpdcd + Cpdca + Ipdid + Ipdia

This says that GDP consists of all wealth produced

domestically wherever it is consumed or invested.

But Cpdca + Ipdia is the totality of exported wealth, so we

can denote this by 'X'.

Therefore:

Y = Cpdcd + Ipdid + X

We can further develop this in terms of total domestic

consumption and investment (Ccd and Iid) by noting that:

Ccd = Cpdcd + Cpacd and Iid = Ipdid + Ipaid

Therefore:

Cpdcd = Ccd - Cpacd and Ipdid = Iid - Ipaid

Rearranging the above equation we have:

Y = Ccd + Iid - (Cpacd + Ipaid) + X

But Cpacd + Ipaid is the totality of imports, denoted by

'M', so:

Y = Ccd + Iid + X - M

This tells us that GDP consists of domestic consumption

(wherever produced), domestic investment (wherever produced), together with

exports less imports.

This is the expenditure (output) equation. Here Ccd + Iid

include all domestic consumption and investment, but textbooks normally include

a separate entry for government expenditure, so we can split Ccd into two

components where Ccd = Ccd(gov) + Ccd(non-gov), and similarly Iid = Iid(gov) +

Iid(non-gov).

Note that government expenditure excludes pensions,

benefits, subsidies and so on,

because these are transfer payments whose effect on consumption and so on are

included in the other components; failing to exclude them leads to double

counting. Borrowing also represents a transfer payment from lender to borrower,

so government borrowing is also ignored. If we now let:

G = Ccd(gov) + Iid(gov)

we have

Y = Ccd(non-gov) + Iid(non-gov) + G + (X-M)

which is the output equation, normally expressed as:

Y = C + I + G + (X - M)

where 'C' denotes Ccd(non-gov), i.e. private consumption,

and 'I' denotes Iid(non-gov), i.e. private investment.

Expenditure (output) equation: Y = C + I + G +

(X-M).

This means: GDP = private consumption (wherever produced) + private investment

(wherever produced) + government expenditure excluding transfer payments + the

excess of exports over imports.

Next we derive the income equation.

Gross domestic income (or national income) - GDI - is the

same as gross domestic product (or output) - GDP, because the money used to buy

wealth is the same as the money value of that wealth, so it is also denoted by

'Y'. As discussed above all private income is allocated to individuals, so

company incomes aren't included in the income equation because all such income

is allocated to individuals in the form of wages, purchases, dividends,

interest, shareholder equity and so on as mentioned earlier.

Recall the private saving definition from the last chapter:

private saving = after-tax income not spent on consumption. Here after-tax

income is gross domestic income less tax, where gross domestic income is

denoted by 'Y' as discussed above, taxation is denoted by 'T', private saving

by 'S' and private consumption by 'C'.

Therefore:

S = Y - T - C

or, rearranging:

Y = C + S + T

This is the income equation.

Note that tax in this context excludes that which funds

transfer payments, as government expenditure excluded transfer payments earlier.

Although in reality much of taxation goes on pensions, benefits and subsidies

etc., those elements are already accounted for in this equation when they are

either spent on consumption or saved by individuals, i.e. in the C + S

elements.

Tax is also paid by companies from profits, but since all

income is allocated to individuals companies' gross profits are regarded as

allocated to individuals, with individuals paying all tax, whether levied on

individuals or on companies.

Income equation: Y = C + S + T. This means:

GDI = private consumption (wherever produced) + private saving + tax (excluding

transfer payments).

Now since both equations represent gross domestic product we

can combine the two so as to express investment in terms of savings:

C + I + G + (X - M) = C + S + T

Subtracting C from both sides gives

I + G + (X - M) = S + T

So overall we have:

I = S + (T - G) + (M - X)

This is the savings identity.

The savings identity: I = S + (T - G) + (M - X). This means

that private investment (wherever produced) = private saving + public saving

(tax less government expenditure) + excess of imports over exports.

This says that domestic investment is bought by the money

that is saved privately and by government out of national income, plus the

money from national income that is spent abroad. Note again that saving can be

by direct purchase of investments (good investment), or by failing to buy goods

and services that are offered for sale - thereby causing unsold stock, unbought

services and increased inventories (bad investment). If imports exceed exports

then there is a net outflow of spending abroad, which would

otherwise buy domestically produced goods and services, so this money

contributes to bad investment. Also if taxation exceeds government expenditure

then money is lost from circulation, and again this contributes to bad

investment. Note that to prevent unnecessary complication all bad investment is

allocated to private investment since most unbought stock and services are

produced by the private sector.

The savings identity is normally expressed as above, but

this hides the good and bad investment aspects, so we can go further and split

S into saving that takes money out of circulation 'Soc' (equivalent to bad

investment) and saving to buy new investments 'Sni' (good investment for future

production), giving:

I = Sni + Soc + (T - G) + (M - X)

Note that Soc includes imported investments, since although

these will be utilised to increase production in the future the immediate

effect is to take money out of circulation.

Of these terms [Soc + (T - G) + (M - X)] represents

transient saving in that if overall it is positive then it corresponds to bad

investment and shrinkage of the economy as firms cut back on production and

hence on the workforce. As the economy shrinks (less national income) people

become fearful for the future so there is less aggregate spending. Less

spending means more paying down of debts, less tax revenue, less good

investment, and also less bad investment - people have less money so can't keep

as much in cash or in banks and can't import as much. Overall in these

circumstances the transient element diminishes until it is zero and a steady

state is reached when I = Sni, but I and Sni after the transient has gone will

be considerably less than they were before because good investment has

diminished along with all other spending.

This is the mathematical version of the paradox of thrift

insight that was recognised in chapters 13 and 15 for the simple economy and

the real economy:

When people cut back on spending and take money out

of circulation the only way to avoid economic contraction is for the government

to spend in order to compensate. Government must put as much new money into

circulation as private individuals have taken out. If the government instead

imposes austerity then it does the opposite and the economy shrinks even

faster.

If however the transient saving element [Soc + (T - G) + (M

- X)] is negative overall, then the economy expands until all spare capacity is

used up, and then if it remains negative there is inflation - see chapter 18.

We can now return to a point

that was made earlier in chapter 4 that change in GDP is taken to imply change

in material wellbeing. A problem is that changes in investment wealth are

counted as changes in GDP, but this wealth in itself does nothing for immediate

material wellbeing, though capital wealth should enable it to grow as it

delivers additional wealth in the future.

So how can we measure material

wellbeing? At first sight and using the designations given above this would

seem to be the same as Ccd for a given accounting period. This is the quantity

of consumer wealth consumed domestically in the period. However it is deficient

as a measure to the extent that some of it is imported, which will only make us

poorer in the future unless it is offset by sufficient exports to pay for it

(if not then the country is living beyond its means which leads to grief

eventually as Mr Micawber pointed out).

Therefore a better measure is one that takes account of exports and imports and

is Ccd + X - M. This measures Ccd together with national income coming from or

going abroad, which is the degree to which the country is well off in terms of

both consumed wealth and entitlement to foreign wealth - which might be

negative. We might of course choose to spend some of the current entitlement on

foreign capital wealth rather than on consumer wealth, but that would affect a

future accounting period. So far as this period is concerned we are well off to

the extent of how well we have lived plus the extent to which we have

accumulated in the present entitlement to live in the future.

Let's call the measurement we

are after AMW for Aggregate Material Wellbeing, noting especially that this is

a measurement for the country as a whole - as indeed are all the other

measurements, it tells us nothing about how wellbeing is distributed between

individuals within the country.

From the above discussion:

AMW = Ccd + X - M

Aggregate material wellbeing is domestic consumption plus

exports minus imports. A more significant measure is AMW per capita, which

gives the wellbeing per person rather than for the population as a whole. It is

easily derived by dividing AMW by the population.

Now from the expenditure

equation (before we brought in government taxation and spending)

Y = Ccd + Iid + X - M

so

Y = AMW + Iid

and

AMW = Y - Iid

This makes sense because it

strips out all investment wealth from GDP, because investment wealth has no

immediate effect on aggregate material wellbeing, though capital wealth should allow

it to grow in the future.

Bringing back government aspects

for completeness we have:

AMW = Ccd(gov) + Ccd(non-gov) + X - M

Aggregate material wellbeing is private and government

domestic consumption plus exports minus imports, or, in terms of GDP:

AMW = Y - Iid(gov) - Iid(non-gov)

Aggregate material wellbeing is GDP minus private and

government domestic investment.

Aggregate material wellbeing for a given time period

can be expressed as private and government domestic consumption together with

exports less imports, or, in terms of GDP, aggregate material wellbeing is GDP

less private and government domestic investment.

Growth or decline in aggregate

material wellbeing can easily be determined by changes from one period to the

next.

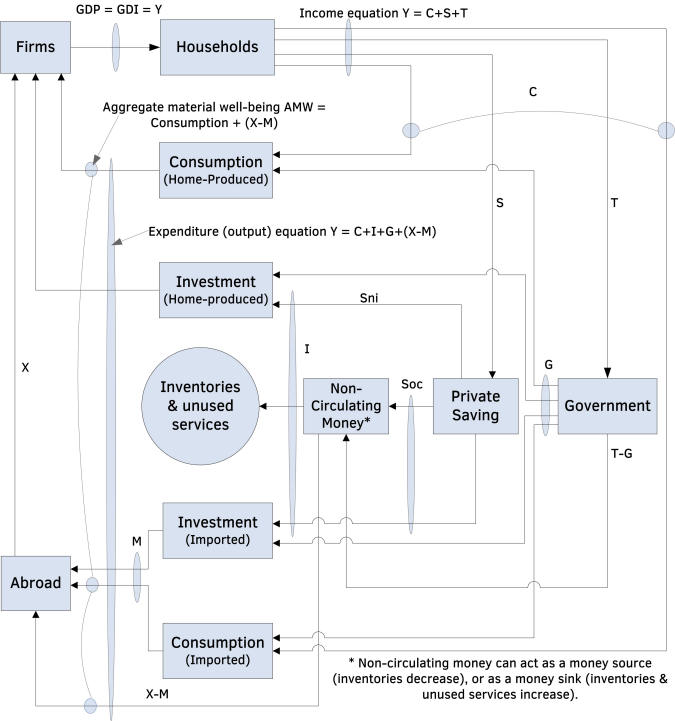

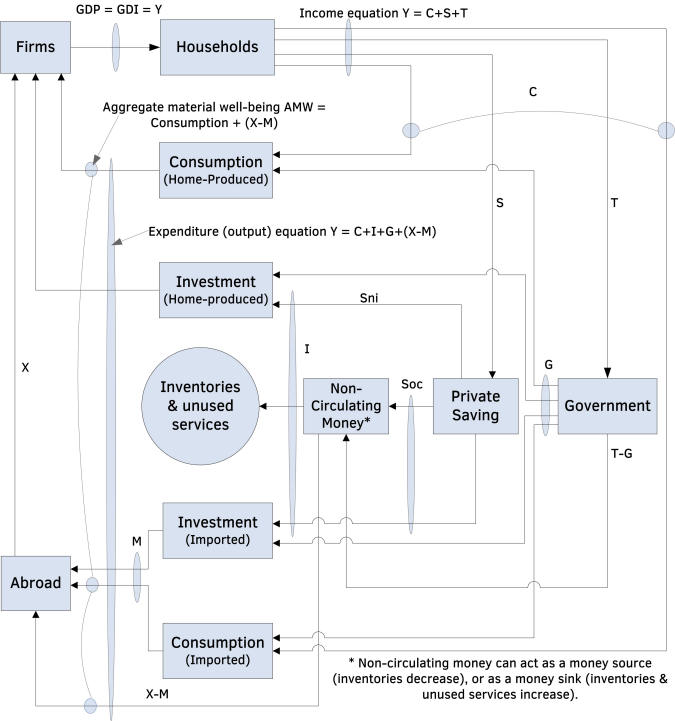

All the foregoing can be shown on a money flow diagram - see

figure 26.1.

This shows the flow of money in relation to new wealth

production in the national economy. By any standards it is complex! To make

sense of it all elements must be strictly defined. I haven't been able to find

any textbook or other source that defines all the terms fully or presents the

relationships in a fully developed diagram so I have worked this up to show the

validity of the equations and identity. I present it here in case it's of any

interest to others.

Figure 26.1: The circulation of money used for new wealth production

in a national economy

Note that services that aren't used

are wasted, they can't be stored for later sale as can inventories, so they

can't act as a money source.