Let me make it clear at the outset that my remarks are not

aimed at specific individuals who work in the sectors targeted. My aim is the

sectors themselves and the collective controlling minds - directors and senior

managers who set the harmful policies that the sectors implement. The

unfettered market philosophy and the freedom conflict working together provide

fertile ground for proliferation of wealth extraction in all its forms. The

modern world is awash with wealth extraction and the sectors are major

employers, so you may well work in one of these sectors yourself. My quarrel is

not with you. Nevertheless my contention is that wealth extraction is

exploitation, which is not only unjust but also damages the economy. However there

is a silver lining in that it represents an enormous reservoir of spare

capacity that is available for redeployment in creating useful humanitarian and

sustainable wealth.

Society contains a vast array of wealth extractors in many

different forms. They are all around us and so commonplace that we take them

completely for granted and regard them as necessary elements of the economy. A

striking feature is that these sectors consider themselves to be essential wealth

creators - their reward reflects no more than the value of the services they

offer - but the wealth they create is dwarfed by the wealth they extract from

those whose main job is to create wealth.

Wealth extraction is excess wealth entitlement gained

from selling goods or services for more than fully informed and unexploited

buyers would be willing to pay.

Wealth is extracted by overcharging. For example, if I was

to offer a service to you that promised a massive increase in confidence, a

worry-free future, the ability to deal easily with any kind of stress and no

more sleepless nights, and charged £500 for it, some might think it represented

a good deal. For your money you would get a home-study course consisting of

thirty hours of mental exercises, ten hour-long guided meditations on a CD, a

book of advice, and self-monitoring checklists to complete every week to

measure progress. I would have prepared all this material by compiling it from

internet searches and I had no qualifications in anything related to what was being

offered and indeed didn't claim any. This might well prove to be a lucrative

business. Unsatisfied customers would be fobbed off by being told that they

hadn't followed the instructions or advice properly, or recommended to repeat

the course, but no refunds would be given. Some people might even be helped by

it. Let's say I made £200,000 each year. That £200,000 would add to GDP because

money had been spent. Also tax had been paid and jobs had been created for a

few assistants dealing with enquiries and sales.

The question is: Does this service represent the

creation of wealth? Wealth has already been defined as that which has

inherent value and can be traded, and generally takes time and effort to

produce or to make available. It consists of goods and services - see chapter 1.

This service can certainly be traded because people give me money for it, it

took time and effort at the outset to prepare the material and some more to

manage the ongoing business, and it's a service, but does it have inherent

value? In a sense it must do because people have come along of their own free

will and paid money for it - aspects that neoliberal philosophy would claim as

giving it value. But in another sense it doesn't because many customers felt

cheated - they thought they were going to achieve something that they didn't

achieve. They paid for something based on expectations, and in all but a small minority

of cases those expectations weren't met. Let's say that after having taken the

course and achieved whatever was achieved customers were asked what they

thought the course was worth, and the average value they came up with was £50. That

represents a more appropriate valuation than £500 because it is assessed from a

position of knowledge. Each buyer's £500 had been earned by their creating

wealth, and they gave it freely, but I took £450 of it by exploiting their

hopes in the knowledge that most would be unfulfilled. I took their wealth

entitlement for myself, with a bit for my staff and a bit for the taxman. What

I did in effect was to extract £450 worth of wealth from each buyer in the form

of entitlement to wealth that they had created, rather than to create new

wealth myself. I was given a free ride by those who were overcharged. Please

note that my use of this example is not intended as a criticism of any similar

services that are on offer. As far as I know they might be very effective and represent

good value. I haven't tried any so I don't know.

People hate being taken advantage of, being ripped

off, but the whole purpose of wealth extraction is to rip people off - to

exploit them in one way or another.

Wealth extractors fall into two main categories, though

there is substantial overlap between them:

The first category exploits people collectively, and includes

all those who have found ways to interpose themselves between product suppliers

and their customers, so that the services they provide give the product

suppliers that use them an advantage over other suppliers. They sell services

that are initially helpful but when they are widely taken up any supplier that

doesn't use them or tries to dispense with them is severely harmed, so no-one

can thereafter afford to be without them. Let's call these ratchet services,

the defining feature of which is that the more they are used the more they have

to be used. Consider a crowd watching a procession. An enterprising salesperson

comes along selling stools to give a better view. Those who buy

the stools do get a better view, but at cost to others behind them who get a

worse view, so they have to buy stools as well. Eventually everyone has bought

a stool and all are in exactly the same position they were in before anyone

bought a stool. No-one except the stool seller has gained anything but

woe-betide anyone who tries to do without a stool; they are guaranteed a much

worse view. Stools don't last forever of course so people have to keep buying

new stools - this procession lasts a very long time! What has happened

is that the stool seller has become rich by providing a service that appeared

to be helpful but in fact contained a trap - it was a ratchet service. The

wealth entitlement enjoyed by the ratchet service provider is paid by those who

buy the relevant products. In effect it represents a hidden product tax. Examples

are all around us and include:

·

adverts that use methods of persuasion, as most do - product

suppliers that are early users benefit at the expense of non-users, but soon

all suppliers have to follow suit and we are now bombarded with adverts from all

sides;

·

credit and debit cards - the first merchants accepting them

enjoyed higher sales that more than offset the fees, but soon all merchants had

to accept them;

·

contactless credit and debit cards - the latest and more

convenient form of card transaction, soon all merchants will be forced to offer

contactless payment;

·

charity muggers ('chuggers') - many of whom are employees of

private companies that are on contract to the charities they represent. They

accost people in the street or make unsolicited phone calls seeking direct

debit commitments, and are paid substantial sums by the charity for everyone

they sign up. All charities must use them or lose out to those that do;

·

non-company-specific discount cards and voucher schemes; and so

on.

Although many of these claim or appear to be free they are

run by companies that make profits and employ staff who receive wages, and it

is the final consumer who pays - very heavily - for all of it. This is the exploitation:

service suppliers using ratchet services pass on their costs to customers, who

pay the associated costs without receiving much if any benefit. Ratchet service

providers and their supporters point out that they help the economy by boosting

spending - people spend money that they otherwise wouldn't, and while there is

some truth in this the spending is mostly of the self-indulgent kind, which when

taken to excess is unsustainable and harmful - see chapter 7. What isn't

claimed but also true is that they distort the market, especially advertising. People

are persuaded to buy products or services that are inferior to or more costly

than others purely because their attention is drawn to them. For example a

company with poor value products but good marketing and advertising can do

better than a company with better value products but poor marketing and

advertising.

Some ratchet services are very convenient to users and in

these cases the service should be retained. It's the wealth extraction element

that should be stopped - see chapter 100 section 100.9.

Also in this category of collective exploitation are tax

avoidance and rent-seeking.

Tax avoidance is discussed in chapter 95 and rent-seeking in chapter 98. Rent-seeking

occurs when individuals and companies influence authorities to favour their

interests over those of others. Such activities include, when done for private

gain, lobbying, campaign funding, seeking to influence the drafting of laws and

regulations, seeking to influence law enforcers and regulators, seeking to

limit competition and so on. In these cases people are overcharged to the

extent that the favoured party obtains subsidies, profits, or direct payments,

or avoids penalties or payments, that without rent-seeking wouldn't occur.

The second category exploits people individually, taking

advantage of need, ignorance, trust, loyalty, laziness, gullibility and so on, and

these exploiters are to be found everywhere,

setting expensive traps for us all. Note that by 'ignorance' I merely mean

lacking relevant information, not lacking in education.

A major form of individual wealth extraction is by wealth

power having taken control of essential resources that others need but lack, so

they must pay the owners for their use. This applies particularly for property

and money, where scarcity in both for ordinary people is driven by the

relentless migration of wealth upwards to the wealthy. As a result property

prices are inflated because of enhanced demand by investors over and above

demand by people who want property to live in, and by public funding

restrictions causing social housing shortages, making prices and rents much

higher than they would otherwise be. Money is kept in short supply for ordinary

people by real wages having been largely stagnant since the early 1980s. However

production hasn't been stagnant, more and more products are available and

wanted, so people have to work more hours and to take on debts to pay for them.

This aspect of wealth extraction - the rich owning more and more essentials

thereby forcing ordinary people to pay to borrow them - focuses on exploitation

in the wealth extraction definition. It underlies the 'hoover-up' phenomenon

discussed in chapter 20, and is discussed further in chapter 54 section 54.3

and chapter 97. Andrew Sayer discusses the subject in detail and explains the

effects very clearly in his book 'Why We Can't Afford the Rich' (Sayer 2015).

Wealth extraction does harm on two fronts. Firstly there is

the deep injustice of people being taken advantage of, which harms members of

society and rewards extractors, and harms the economy to the extent that money

is taken from poorer people who spend more and given to richer people who spend

less. Secondly there is major harm to the economy in the form of enormous

waste, which is the useful work that the extractors and their employees could

do that is not being done - the wealth they could create is lost. Instead,

although they are doing work of a sort, their efforts are not devoted to the

creation of wealth but to extracting wealth from others, so the work they do is

unproductive. They are being carried on the backs of those who do create wealth.

Perhaps the saddest thing is that many who work in these sectors are

particularly bright, talented and innovative, and the wealth they could create

would be of very high quality. The sectors are so lucrative that they are

easily tempted away from useful work by the rewards, and don't have to wrestle

with their consciences because they are widely admired and thought of as wealth

creators.

Wealth extraction is unjust, extremely wasteful, and

should be eliminated by appropriate legislation. What stops it being eliminated

are the vested interests of those who profit from it and the failure to

recognise that it exists by those who pay for it.

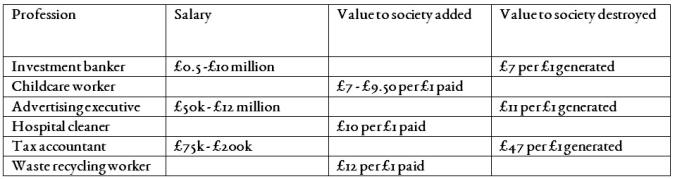

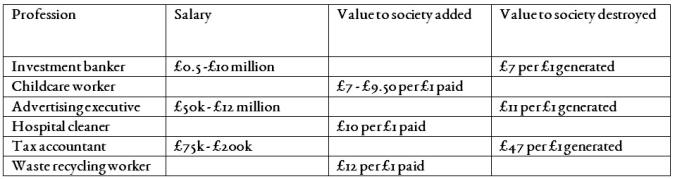

The New Economics Foundation released a report in December

2009 titled 'A Bit Rich: Calculating the Real Value to Society of Different

Professions'.

They analysed the impact of six professions on society, taking account of all

associated costs that don't appear on company balance sheets. Their findings

are summarised in table 36.1. This shows the extent to which particular

professions contribute or extract from society. The full report, downloadable

from the web page cited, provides the detailed calculations and external

references that lead to and support these perhaps surprising results.

Wealth extraction also includes theft in all its forms

including tax evasion, but theft is already illegal so it isn't considered

further.

Table 36.1

When a service is sold for more than properly informed and

unexploited buyers would pay for it, and the full value of the sale added to

GDP, the excess value over its true worth represents double counting, because

that amount was already included in GDP when the buyer earned it. Transferring

it to another by extraction adds nothing to real economic growth and shouldn't

add anything to GDP. In effect wealth extraction is a transfer payment, and as

discussed in chapter 26 transfer payments are ignored (or should be) in

calculating GDP.

Some might still think that the creation of jobs makes it

worthwhile, but the income earned by extraction workers is paid from extracted wealth

so the people doing those jobs represent resources that aren't helping society

or the wealth-creating economy.

Wealth extraction adds to GDP, generates taxes and

creates jobs, but makes society as a whole no better off. It does NOT represent

the creation of new wealth. All it does is transfer wealth entitlement from

those who have it to those who have found clever ways to take it for

themselves.

We don't count the proceeds of theft as contributing

to GDP, so why should we count the proceeds of wealth extraction? Society

benefits from neither, the only difference is that one is illegal and the other

isn't.