A moral hazard is an incentive to do something that is

beneficial to the person or company that does it but is harmful to others, and

the unfettered market economy is full of them - see chapter 29. For example

when a salesperson is paid a bonus for every customer they sign up for a

particular product (as most are) they have every incentive to emphasise the

benefits and hide the disbenefits, even when the product is likely to be

detrimental to the customer. What's more the most successful of such

salespeople are often those least hindered by conscience.

Moral hazard is a prominent feature of the banking system as

it is currently set up, and it became very much worse as banking regulations

were progressively weakened and removed from the 1980s onwards.

To illustrate the fertile ground for moral hazard that the

banking sector presents I ask three simple questions that were first asked (along

with many others) by James Robertson (Robertson 2012 Chapter 3).

i.

Who should create money?

ii.

How much money should be created?

iii.

Who should decide where to allocate newly created money?

In a truly democratic society the answers should surely be:

i.

A public body, acting in the public interest, independent of both

government and private interests, operating transparently to criteria set by

government.

ii.

As much or as little as is judged by experts, who are fully

accountable for their judgements, to be in the best interests of the public.

iii.

The government of the day.

In stark contrast, the answers currently in place are:

i.

Banks, acting purely in their own interests (banks have created

97% of the money in circulation - bank money - whereas the BoE has created just

the remaining 3%, as notes and coins).

ii.

As much or as little as best serves the interests of the banks.

iii.

The banks themselves, with the object of maximising their

profits.

In light of these answers how can anyone can believe that

the system serves the public interest? Yet there are such people, and they

aren't just those who profit by it. Neoliberals believe that banks operate in a

free market and anything that the free market does is bound to be in the public

interest. They are wrong on both counts.

Ultimately it is the government that is responsible for the

economy, so the government always provides the backstop for any mismanagement

by the banking system. In this respect banks enjoy a very privileged position

relative to any other private business. The government permits banks to operate

in this way and to create the country's money supply with very little restraint,

yet the value of that money and the validity of the corresponding debts (no

matter how toxic) are guaranteed by the taxpayer, as the 2008 bailout clearly

demonstrated. This creates a very severe moral hazard. Sir Mervyn King recognised

this when he said: "Of all the many ways of organising banking, the worst

is the one we have today."

We entrust private banks with the responsibility of

creating the national money supply, and permit them to do so in the manner that

best suits themselves, but the value of the money they create is guaranteed by

the taxpayer. When operating successfully the banks enjoy huge profits, but

when reckless lending leads to widespread defaults it is the taxpayer that

suffers the losses.

Heads the banks win; tails the taxpayer loses.

This effect is a severe negative externality. The banking

service benefits the banks, its managers and shareholders, but when things go

wrong it severely harms everyone. It is in effect a polluter, and although the

pollution isn't visible until crises erupt, at those times the pollution

unleashes its toxic effects on everyone.

Andrew Haldane - Chief Economist and Executive Director,

Monetary Analysis and Statistics, BoE - in a speech to the Institute of

International and European Affairs in 2011, estimated the cost to the world of

the banking failures in 2008.

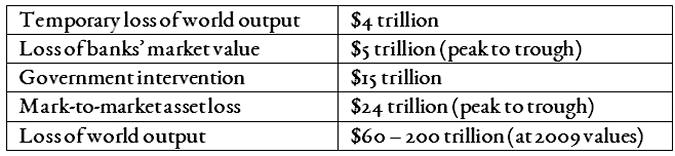

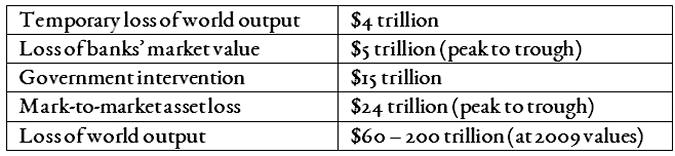

He presented the following estimates (US dollars):

Table 50.1: World cost of 2008 banking failures

Let's just take a moment to digest that last figure. Between

$60 and $200 trillion in wealth value lost to the world. That represents the

wealth that would have been created if the crisis hadn't happened, and is now

irrevocably lost. To put it into context world output in 2011 according to the

World Bank was $71 trillion,

so if Haldane's estimate is right then between one and three years' worth of

world wealth creation was lost. That's a staggering loss.

With that wealth we could have stabilised carbon

emissions at sustainable levels,

guaranteed clean water for everyone,

ended world poverty,

and stopped the destruction of the biosphere. That's the

level of catastrophe that the banking system unleashed.

In fact the real damage of the 2008 crash may well be

environmental. Because of it we have devoted precious efforts and resources

just to keep economies afloat and environmental concerns have gone on the back

burner, making eventual catastrophe all the more likely.

Haldane in the same speech also estimated the total implicit

subsidy to UK banks as £10 billion in 2007, £55 billion in 2008 and £100

billion in 2009. The subsidy is implicit because it manifests as much lower

costs to banks than would be the case if banks rather than taxpayers bore the

risks involved. For example when depositors (including you and me) know that

banks will be rescued if they fail then we don't worry about what the banks do

with their money and we are satisfied with a low rate of interest on our

deposits. If on the other hand we knew that no rescue would occur, and that in

the event of bankruptcy we would lose our money, then we would take great

interest in what banks did and would want a much better rate of interest before

taking the risk of trusting banks with our money. Note that the above subsidies

don't include the subsidy from society to banks for lending real wealth whereas

banks take all the profit (see chapter 48), and they don't include the interest

payments from taxpayers to banks for the government bonds that they own when

there is no need for any such payments - see chapter 44. Also, and more

importantly, these subsidies represent a completely separate cost to the cost

of the damage to world output that the banking failures caused. The subsidies

are what society pays to banks so that they can continue to provide services at

great profit to themselves, whereas the lost output is what it cost society

when banks over-reached themselves. For comparison purposes the cost to the UK

taxpayer of the NHS is about £120 billion per year (2016/17).

Banks have every incentive to grow as big as possible,

because the bigger they are the more likely they are to be bailed out when they

fail. They try their hardest and largely succeed in becoming 'Too Big To Fail'

because doing so represents for them a major safeguard. In fact it isn't just

size that makes them more likely to be bailed on failure, at least as important

is interconnectedness. The more likely it is that one bank failure will lead to

other bank failures again the more secure is the entire sector and the more

insecure is the taxpayer.

Sir Mervyn King put the point very succinctly on page 15 of

his talk referenced above:

It is hard to see why institutions whose failure cannot

be contemplated should be in the private sector in the first place.

Other helpful references on bank subsidies include the

Positive Money website,

and a BoE paper in May 2012 that addresses the different ways of estimating the

subsidies.

What was it that changed banks from the old regime when they

took great pride in integrity and probity? A regime that prevailed until the

1980s and was characterised by the phrase 'my word is my bond'; when reputation

was everything both for individual bank managers and for the banking system as

a whole. Banking was always profitable, and the profits represented easy and

unjustified money, but the profits were nothing compared to those in more

recent times, and bank managers and directors were paid no more than people

with similar qualifications, experience and responsibilities in other

professions. As globalisation gathered pace with the removal of restrictions on

global capital flows it became easier and more profitable for banks to set up

businesses in other countries both to compete with existing banks in those

countries and to get round their own country's restrictions. Countries with

lower regulatory and taxation burdens were very attractive to foreign banks,

and this put pressure on home governments to reduce their own regulations and

taxes to avoid losing business to foreign countries. This began the 'race to

the bottom' in terms of regulation and taxation (Kay 2015 p20 and Rodrik 2012 pp263-264).

One of the major relaxations was in the rules relating to securitisation

- the packaging up of banks' long-term loan contracts and selling derivatives

based on them in the market to investors. Until that time banks had to take

great care with regard to whose debts they were willing to finance because they

retained those debts until they were paid off, so they were on the hook for the

duration of the loan in the event of the borrower defaulting. This caution

provided a natural brake on banks' enthusiasm to take on more and more debt -

the more debts they took on the more profit they made, but the more likely a

significant default would break the bank. After securitisation banks could be a

lot less cautious about borrower creditworthiness because the buyers of the

securitised loans were at risk of default, not the banks themselves. There was

then almost no restriction on the amount of debt they could finance without

risking their own security, though they were risking the security of the whole

financial system - see chapter 54.

As profits grew, so did bank management and director

salaries and bonuses - to almost unimaginable levels - as there was little to

stop them. Indeed so much was taken from banking profits in management payouts

that the initial bailout of £50 billion for UK banks following the 2008 crash

was equal to just 10% of those payouts between 2000 and 2007 (Brown 2011 p106).

At this time greed took over from probity as the defining feature of the

banking sector. So deep was the culture of greed that bankers were quite

willing to break the law in the interests of even more profit - mis-selling of

payment protection insurance (PPI), money laundering, LIBOR fixing, predatory

lending, forgery, fraud, foreign exchange manipulation and much more.

And who was and still is it that pays for all those profits,

salaries and bonuses? It is ordinary people, those who take on debts, either

by choice or necessity. To pay the banks people have to work longer hours, have

two or more jobs, have both partners in a relationship working, and even then

still have to rely on credit cards (yet more profit for banks) to make ends

meet. An increasing number of people have become slaves to stress and misery as

a result.

It is a sobering thought that if all associated costs of the

banking sector were to be paid by the sector itself banking would very likely

not be profitable at all. This is what John Kay said:

If banks had to pay for the insurance provided by the

doctrine of 'too big to fail', the trading activities in which they privately

engage simply would not take place, or at least would not take place on the

current scale. Much, perhaps all, of the profitability of these institutions

comes from the willingness of lenders (including other financial institutions)

to make finance available on terms that would, in the absence of such public

support, be regarded as too risky. (Kay 2015 p140)

It is worth pointing out that Kay doesn't include the

interest charges in excess of default risk that society pays as argued in

chapter 48, so if we were to deduct these from bank profits then I think we can

be quite confident that the banking system as it is currently structured - with

such a high degree of integration and therefore so high a risk premium - would

not be profitable.

We can therefore regard ALL of the banking system's

profits, together with the salaries and bonuses of everyone employed in other

than the everyday banking services that society needs, together with all the

crisis insurance paid by society, as a massive subsidy from society to banks. Subsidies

are transfer payments - in this case by wealth extraction - and as such

represent a massive and completely unjustified burden on society.

All this begs the very serious question put by Mervyn King

above: Why is banking a private sector activity when it receives such massive

support from society? No-one would dream of providing such support to any

other private business. I suspect it is because the support is largely hidden,

but no less real for that.

A very pertinent and telling quotation attributed to Mayer

Amschel Rothschild sums up the situation well: "Give me control of a

nation's money and I care not who makes its laws."

If ever an event showed the economy's dependence on

and vulnerability to the activities of the banking sector it was the 2008 crash.

To avoid similar and potentially worse events in the future radical overhaul of

the banking system is therefore urgently required. But such is its power and

hold over world governments that all that has happened and is intended to

happen is some minor tinkering around the edges.

The banking sector puts up massive resistance to any

proposal to restrict its activities and it does itself no favours by doing so. Surely

its leaders can see for themselves the damage that their activities have

already caused both to society and themselves, and will cause again on an even

bigger scale in the future if they are left to their own devices. Perhaps they

believe that they have learned all necessary lessons from the last crash and

can avoid a future one by self-restraint? If so they are deluding themselves

by forgetting the main factor that promotes success during economic expansion, which

is risk-taking. Those banks that take the biggest risks attract the most

profits, and any bank that exercises restraint is left behind. In fact if a

cautious bank is left too far behind then it becomes a target for a hostile

takeover by a more profitable bank, which then continues its risky strategy but

on a bigger scale. A strategy of exercising caution on the part of a single

bank sets up what is in effect a positive externality - see chapter 29 - in

that the whole sector becomes safer because the degree of interdependence is

less fragile (the extent depending on the size of the single bank), but the

single bank bears all the costs. Other banks can enjoy the safer climate

without any cost to themselves. In effect they become free-riders on the cautious

bank's back. It is the same as if a single household pays for street lighting

on the road where they live. The lighting benefits everyone on the road but the

costs are borne by the single household. I don't know of any single household

that provides street lighting, and I don't believe that any single bank will

exercise adequate caution when the others don't.

It is this feature of banking - the bigger the risks the

bigger the profits - that drives all banks to take bigger and bigger risks, in

the current climate banking competition enforces it. Managers that are inclined

to caution either suppress it or suffer from competition with more profitable

banks that don't exercise caution. If their banks suffer then they are sacked

and replaced with someone less cautious. It's the effect of banking freedom

allowing bad practices to drive out good practices that was discussed in the Introduction.

A comment by Charles "Chuck" Prince (former chairman and chief

executive of Citigroup) sums up the situation:

As long as the music is playing, you've got to get up

and dance. We're still dancing.

When restrictions are imposed from outside the sector all

banks are subject to them so competition driven by risk disappears, and this

benefits not only society but the entire banking sector by becoming safer. Other

industries that impose risks on society are subject to restrictions, and

everyone including the industries themselves recognises the need for them. Banking

should be no different, indeed if anything the restrictions should be more

severe for banking because the potential damage is so much greater.

Can it be that bankers don't care about safety, knowing that

whatever damage their activities cause to society as a whole they themselves

will likely keep their gains? I sincerely hope not. Selfishness on that scale

is truly frightening. A very notable feature of the 2008 crash is that no bank

directors or managers suffered any penalties other than disgrace after their

reckless lending. I am convinced that sending the worst offenders to jail for

their misdeeds would help to concentrate all similarly placed minds very

forcefully. Benefits would be weighed much more carefully against costs if

those costs included significant jail terms!

In any other walk of life if someone is asked to guarantee a

debt that responsibility is taken very seriously. Yet governments guarantee

bank debts (bank money), not only for existing debts but for any future debts,

and banks are free to take on whatever debts they wish.

Banking is generally regarded as only one factor amongst

many that contributed to the Wall Street Crash of 1929, but bank credit fuelled

the excesses in production during the 'roaring twenties' and fuelled much of

the investment in the stock market during its meteoric rise in that decade. Share

prices were rising not because companies were worth more but because buyers

were much more willing to buy than sellers to sell - and their willingness came

from the fact that easy credit fuelled share price rises - a vicious circle

that created a massive bubble. Banks created the money to buy them on the

collateral of the shares themselves - a classic positive feedback mechanism - see

chapter 52. The bust came as busts always do when new buyers were no longer

available, at which point investors started selling shares to avoid losses and

share prices started to drop. Banks then forced investors who had borrowed in

order to buy shares to sell yet more shares to avoid them becoming overdrawn,

and that accelerated the price drops in an ever steepening downward spiral. Hence

without the activities of banks in fuelling the over-expansion of production

and the stock market bubble the crash would either have been very much less

severe or wouldn't have happened at all.

Following the 2008 crash there has been a strengthening of

the Basel III accords (a global voluntary regulatory framework) consisting of

three linked limits - minimum capital adequacy ratios, minimum leverage ratios,

and minimum liquidity ratios. They are intended to allow banks to survive for

longer during periods of stress such as that experienced during the 2008 crash.

They may well succeed to some extent, but at best all they will achieve is to

extend banks' survival time, they certainly won't fix the system (Ryan-Collins

et al. 2012 Sections 5.1.1, 5.1.2 and 5.2 pp95-100). What they also don't take

into account is banks' ability to find ways round regulatory limits. Banks have

every incentive to circumvent limits because the result is increased profits

(often massively increased profits), whereas regulators have practically no

incentive to increase regulation. Banks employ armies of well-paid experts to

plead their case to regulators and politicians and to show that what they

propose will be good for the economy, and that what regulators propose (if

banks don't like it) will be bad for the economy. Regulators stand no chance

against such massed might. Banks have shown themselves to be very adept at such

practices in the past and there is no reason to hope that they will be any less

so in the future. For these reasons it is very unlikely that restrictions,

however stringent, will provide a cure for the severe dangers that are inherent

in the system. I believe that nothing less than a complete and radical redesign

of the systems that create and allocate money will provide a permanent cure.

Without an effective and permanent cure for the ills

of the banking system we can expect another great crash, when in all likelihood

the sector will be 'too big to bail'.

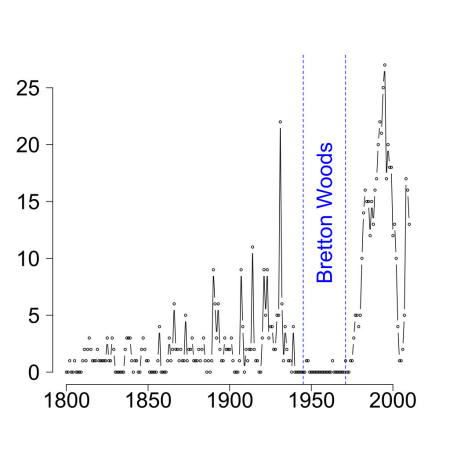

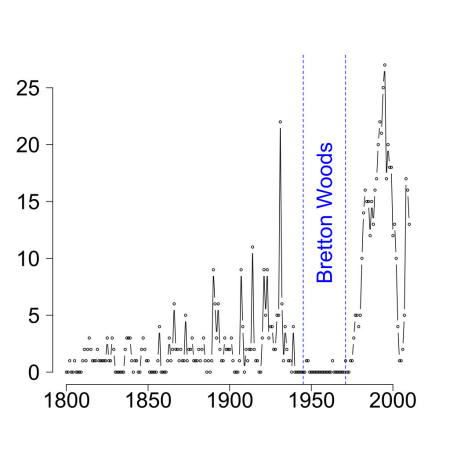

In addition to major crashes, such as happened in 1929 and

2008, minor crashes (known as downturns in the business cycle - driven by

positive feedback in money creation - see chapter 52) and lower level banking

crises happen all the time. These are also very damaging to society in causing

loan foreclosures with loss of homes for individuals and loss of output and

jobs for businesses. The following chart, figure 50.1, shows the number of

countries having a banking crisis in each year since 1800. Note especially the

Bretton Woods period after the Second World War. This represents a very unusual

and stable period in economic history and is examined in more detail in chapter

67.

Figure 50.1: From Wikipedia 'List of Banking Crises' By

DavidMCEddy (his own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons. Source

data taken from Reinhart and Rogoff 2009.

In summary, in its current form, banking has the

following characteristics:

i.

it is based on deception;

ii.

it does major damage to society on a regular basis during business cycle

downturns; and

iii.

it does almost unimaginable damage to society when there are major economic

crises.

For all that we get services that can easily be provided

by other means - see chapter 55.